Liver transplantation has improved the quality and quantity of life for patients requiring transplantation due to having cirrhosis, liver malignancy, or acute liver failure [1]. Currently, in the United States, the overall survival post-liver transplantation at one year is about 94%, with 5-year survivals of 81% and 10-year survivals of up to 62% for all indications [2]. Although liver transplantation improves outcomes, there are associated risks, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, infection and notably an increased risk of malignancy which impacts survival [3].

The risk of cancer post-liver transplant is about 2-3 times that of age and sex-matched healthy controls [4], with higher rates in younger individuals [5]. The risk of developing a malignancy at 10 years post-transplant in general has been reported as between 20-32% [6]. Skin cancer is the most common malignancy post-liver transplantation with a 30x fold risk as compared to the general population [7], accounting for 40% of malignancies. Further increasing the significance of developing a malignancy post-transplant is that mortality is increased as compared to a matched non-transplant recipient [8].

In this issue, Gitto et al. report Italian data regarding extrahepatic, non-skin cancer (ESNSC) in liver transplant recipients transplanted from 2000 to 2005 [9]. In this 367-patient study with a median follow-up of over 15 years, 47 patients (12.8%) developed an ESNCS. ESNCS, not surprisingly, was associated with lower 10-year survival (46.8% compared to 68.1% without ESNCS). The most common malignancies in this series included lung cancer (32%), colon cancer (26%) and oropharyngeal malignancies (11%). An underlying indication for liver transplantation of hepatitis B and alcohol related liver disease was associated with an increased risk of ESNCS. Univariate analysis showed that de novo non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes mellitus post-transplant were associated with an increased risk of ESNCS. On multivariate analysis, post-transplant diabetes was associated with twice the risk of developing an ESNSC compared to those without, while de novo non-alcoholic fatty liver disease was no longer significant.

Previous studies looking at cancer occurrence have typically analyzed all malignancies, including skin cancer and lymphoproliferative disorders in addition to solid organ cancers [10]. This typical method of analysis of including all malignancies helps to understand the overall risk of malignancy; however, not all malignancies are identical with regards to prognosis or risk factors. For instance, skin cancer risk factors (sun exposure) or lymphoproliferative disorders (Epstein-Barr virus) differ from solid organ malignancies, which are generally less well-defined save for de novo hepatocellular carcinoma. Furthermore, skin cancer and lymphoproliferative disorders are different entities regarding prognosis compared to ESNSC.

Several risk factors have been associated with extrahepatic non-skin cancer in the previous literature including etiology for liver transplantation (e.g., primary sclerosing cholangitis, alcohol associated liver disease, hepatitis C), other medical conditions (such as the presence of Epstein-Barr virus or Helicobacter pylori), tobacco and alcohol use, sex, and ethnicity [7]. Diabetes, which is extremely common post liver transplant [11] has been associated with increased rates of malignancy in the general population, especially that of colon cancer [12] although data supporting this association in liver transplant recipients have been limited.

This study [9] provides an important addition to the literature and is unique in its focus on ESNSC. A key strength of this analysis is the long follow-up with a median follow-up of 15 years which is one of the longest periods of follow-up reported to date. The multicentre nature of this study also adds to its value. The finding of a potential association of diabetes with developing ESNSC is an important observation, although this needs to be confirmed by other analyses. If this association of diabetes with malignancy is confirmed, potentially optimizing diabetes management could reduce the risk of developing malignancy and cardiovascular events, improving patients’ survival and quality of life.

There are some important limitations with this study that may limit its generalizability. This cohort is on the smaller side consisting of patients who underwent transplants from 2000-2005; there are multiple studies with cohorts of over 1000 patients [10]. This study is retrospective and there is limited data about smoking history and family history of malignancy. Given that there is a potential link between tobacco use and developing pre-diabetes and/or diabetes [13], the lack of information about tobacco could be a confounder given tobacco is associated with an increased risk of lung cancer and head and neck cancers [7]. Data regarding which malignancies were associated with diabetes are unfortunately not reported.

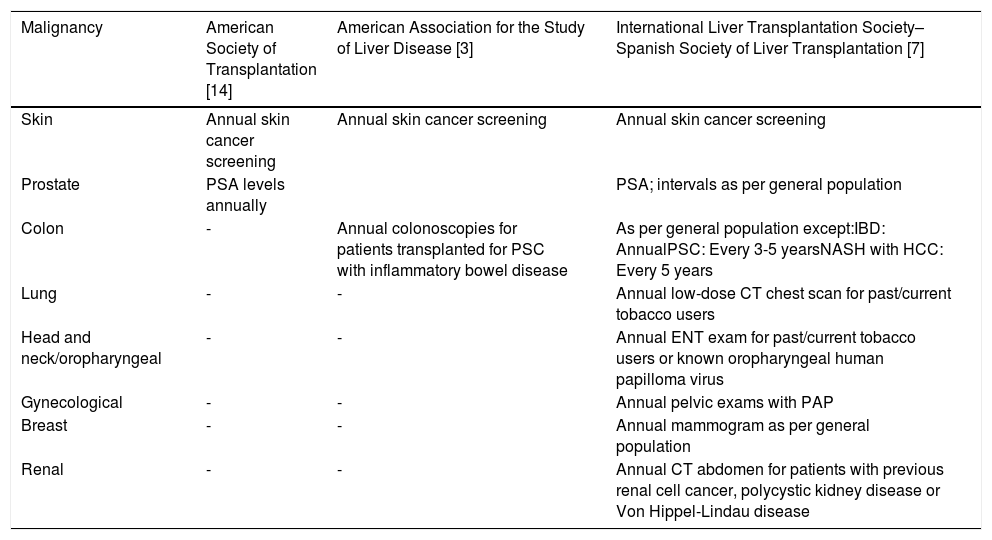

Given the increased frequency and mortality of malignancy in patients post-liver transplantation, screening strategies for malignancy are an important part of post-transplant care. Although an important area of clinical management, there has been limited guidance on this topic [3,14] until the recent publication from the International Liver Transplantation Society–Spanish Society of Liver Transplantation Consensus Conference [7] (Table 1). Studies evaluating long-term risks of malignancy are important for patient care to best utilize resources for screening in a cost-effective manner via guidelines. If the risk of malignancy changes over time, alteration of screening intervals may be warranted. Given that the screening rate for malignancy is lower in patients post-transplantation than the general population [15], if the risk of malignancy decreases over time, screening intervals may be able to return to that of the general population to improve adherence.

Published Screening Recommendations Post Liver Transplantation

| Malignancy | American Society of Transplantation [14] | American Association for the Study of Liver Disease [3] | International Liver Transplantation Society–Spanish Society of Liver Transplantation [7] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | Annual skin cancer screening | Annual skin cancer screening | Annual skin cancer screening |

| Prostate | PSA levels annually | PSA; intervals as per general population | |

| Colon | - | Annual colonoscopies for patients transplanted for PSC with inflammatory bowel disease | As per general population except:IBD: AnnualPSC: Every 3-5 yearsNASH with HCC: Every 5 years |

| Lung | - | - | Annual low-dose CT chest scan for past/current tobacco users |

| Head and neck/oropharyngeal | - | - | Annual ENT exam for past/current tobacco users or known oropharyngeal human papilloma virus |

| Gynecological | - | - | Annual pelvic exams with PAP |

| Breast | - | - | Annual mammogram as per general population |

| Renal | - | - | Annual CT abdomen for patients with previous renal cell cancer, polycystic kidney disease or Von Hippel-Lindau disease |

Overall, Gitto et al.’s work [9] provides some important areas for exploration and confirmation and highlights an important point regarding the different characteristics of skin cancer and lymphoproliferative disorders compared to ESHNC. Understanding the true impact of diabetes mellitus post-liver transplant on the incidence of malignancy and the type of malignancy affected could significantly impact patient care. Future studies of malignancy post liver transplantation should explicitly evaluate the risk of diabetes and control for confounders such as tobacco use. Lastly, in studies analyzing all post-liver transplant malignancies, performing subgroup analyses of skin cancer, lymphoproliferative disorders, de novo hepatocellular carcinoma and ESHNC would significantly improve our understanding of post-liver transplant malignancy and hopefully allow for better outcomes for patients.

Funding SupportNo funding to declare.