Patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 3 (GT3) infection are resistant to direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatments. This study aimed to analyze the effectiveness of sofosbuvir (SOF)+daclatasvir (DCV) ± ribavirin (RBV); SOF+velpatasvir (VEL)±RBV; SOF+VEL+voxilaprevir (VOX); and glecaprevir (GLE)+pibrentasvir (PIB) in the treatment of HCV GT3-infected patients in real-world studies.

Articles were identified by searching the PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases from January 1, 2016 to September 10, 2019. The meta-analysis was conducted to determine the sustained virologic response (SVR) rate, using R 3.6.2 software.

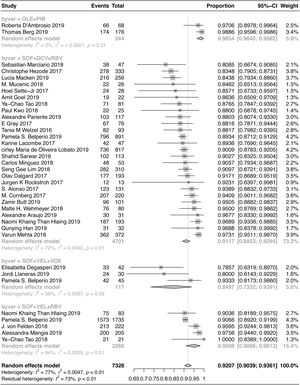

Thirty-four studies, conducted on a total of 7328 patients from 22 countries, met the inclusion criteria. The pooled SVR rate after 12/24 weeks of treatment was 92.07% (95% CI: 90.39–93.61%) for the evaluated regimens. Also, the SVR rate was 91.17% (95% CI: 89.23–92.94%) in patients treated with SOF+DCV±RBV; 95.08% (95% CI: 90.88–98.13%) in patients treated with SOF+VEL±RBV; 84.97% (95% CI: 73.32–93.91%) in patients treated with SOF+VEL+VOX; and 98.54% (95% CI: 96.40–99.82%) in patients treated with GLE+PIB. The pooled SVR rate of the four regimens was 95.24% (95% CI: 93.50–96.75%) in non-cirrhotic patients and 89.39% (95% CI: 86.07–92.33%) in cirrhotic patients. The pooled SVR rate was 94.41% (95% CI: 92.02–96.42%) in treatment-naive patients and 87.98% (95% CI: 84.31–91.25%) in treatment-experienced patients.

The SVR rate of GLE+PIB was higher than other regimens. SOF+VEL+VOX can be used as a treatment regimen following DAA treatment failure.

According to the reports of the World Health Organization (WHO), up to 71 million people were infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) around the world in 2015 [1]. The high rate of viral replication and mismatch in the process of replication leads to frequent viral mutations. The antiviral treatment regimen in the interferon era mainly included pegylated interferon, combined with ribavirin. However, this regimen had a low sustained virologic response (SVR) and was associated with more drug-related adverse events. With the clinical application of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), the SVR rate significantly improved, and toxicity declined. However, previous studies have reported that the antiviral effectiveness of DAAs varies per genotype.

The SVR rate of HCV genotype 3 (GT3) infection is relatively lower than that of other genotypes. In recent years, considerable progress has been made in the antiviral treatment of HCV-GT3 infection, using new drug regimens and drug combinations. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicine Agency (EMA) approved the regimens, containing sofosbuvir (SOF)+daclatasvir (DCV)±ribavirin (RBV) in 2015 and SOF+velpatasvir (VEL)±RBV in 2016 for the treatment of HCV-GT3 infection. They also approved SOF+VEL+voxilaprevir (VOX), as well as glecaprevir (GLE)+pibrentasvir (PIB), in 2017 [2].

In this meta-analysis, we systematically evaluated the pooled SVR rates of DAA regimens against HCV-GT3 infection in real-world studies.

2Materials and methods2.1Literature search strategyThe following terms were used to search PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library from January 1, 2016 to September 10, 2019: [“sofosbuvir” AND “daclatasvir” OR “Sovaldi”] OR [“sofosbuvir” AND “velpatasvir” OR “Epclusa”] OR [“sofosbuvir” AND “velpatasvir” AND “voxilaprevir” OR “Vosevi”] OR [“glecaprevir” AND “pibrentasvir” OR “Mavyret”].

2.2Inclusion and exclusion criteriaTwo researchers (ZLW and ZY) scanned the titles and abstracts of the papers independently and assessed eligible trials, according to the inclusion criteria. Articles, which were potentially suitable based on the inclusion criteria, were extracted for a full-text review. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. The inclusion criteria for the articles were as follows: subject (assessment of patients with chronic HCV infection); intervention (SOF+DCV, SOF+VEL, SOF+VEL+VOX, or GLE+PIB); primary outcomes (SVR rate after 12/24 weeks); and study design (real-world studies). On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) unavailability of valid data related to HCV-GT3 infection; 2) inclusion of less than 10 patients in the study during treatment or follow-up for effectiveness evaluation; and 3) summaries, case reports, or meta-analyses.

2.3Data extractionTwo authors (ZLW and ZY) read the full-text of articles independently. The information extracted from the articles included the demographics, main clinical characteristics of the patients, resistance-associated substitutions (RASs), average HCV RNA concentration at baseline, treatment regimen, drug dosage, therapy duration, SVR12/24, and virologic failure. Also, the authors resolved discrepancies by consultation with a third party (XHC).

2.4Data analysisMeta-analyses were conducted to determine the pooled SVR rate in all populations and subgroups, using the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation in a random-effects model. Chi-square test was performed to compare the SVR rates of multiple groups. Also, Egger's test was conducted for evaluating potential publication bias. All analyses were performed in R 3.6.2 software with a meta package.

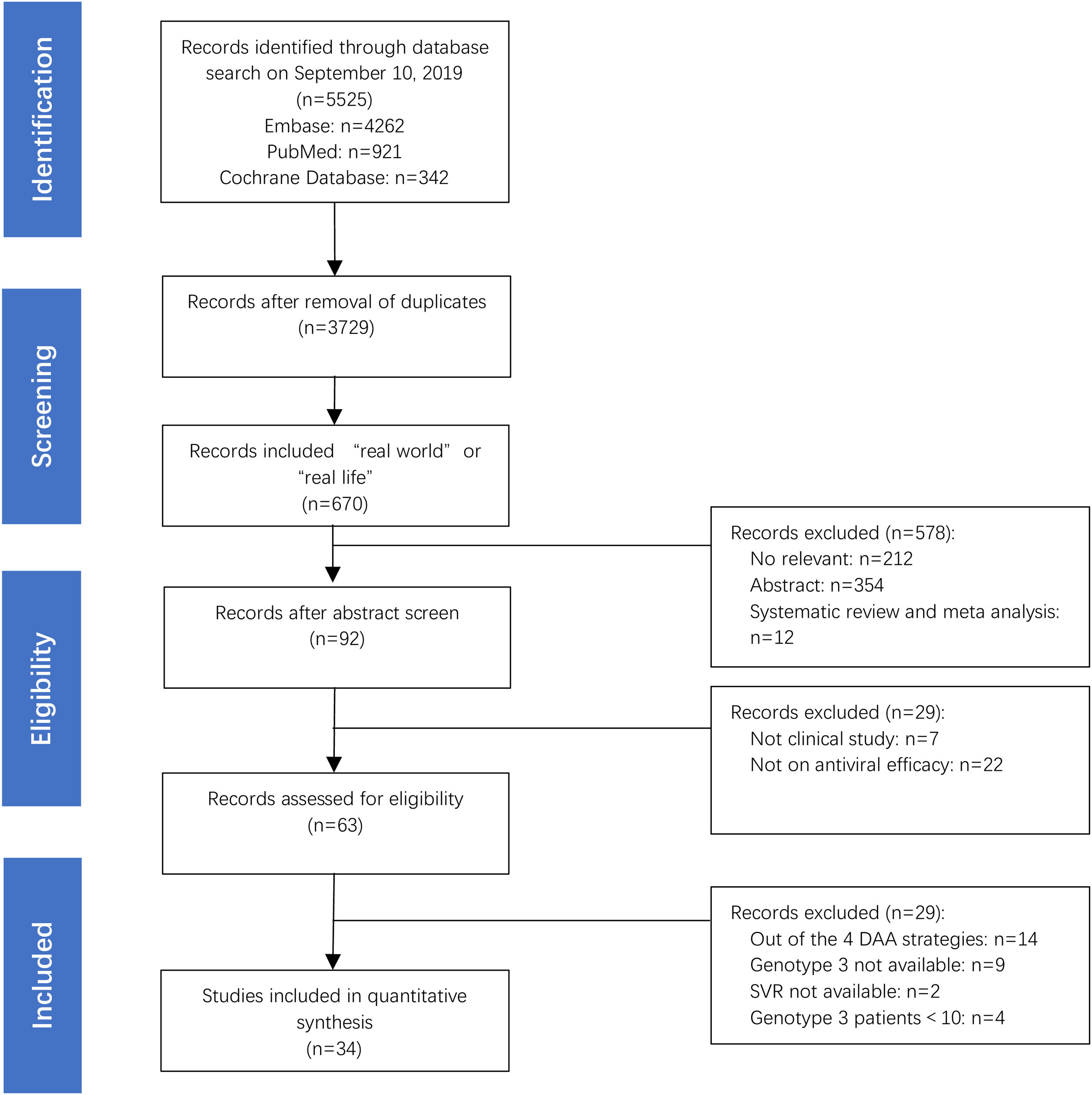

3Results3.1Main characteristics of the studies and populationsA total of 7328 HCV GT3-infected patients were examined in 34 studies, which were selected among 5525 screened articles (Fig. 1). The studies were conducted in 22 countries: Germany (n=6), Brazil (n=4), USA (n=3), France (n=3), India (n=3), Italy (n=3), Pakistan (n=3), Spain (n=3), China (n=2), Myanmar (n=2), Norway (n=2), Sweden (n=2), Argentina(n=1), Austria(n=1), Denmark(n=1), UK(n=1), Finland(n=1), Ireland(n=1), Malaysia(n=1), Netherlands(n=1), Singapore(n=1), and Thailand (n=1). In 34 studies, there were 37 treatment regimens, of which 73% were SOF+DCV±RBV (27/37, 73%), followed by SOF+VEL±RBV (5/37, 14%), SOF+VEL+VOX (3/37, 8%), and GLE+PIB (2/37, 5%), respectively. The total number of patients included is 7328, 4701 patients were treated with SOF+DCV±RBV (4701/7328, 64%), followed by SOF+VEL±RBV (2266/7328, 31%), GLE+PIB (244/7328, 3%) and SOF+VEL+VOX (117/7328, 2%), respectively.

A summary of the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients is presented in Table 1. Patients with chronic HCV-GT3 infection, included in these real-world studies, also had diseases, such as hepatitis and decompensated cirrhosis. Some of these patients had refractory comorbidities, such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), HIV/HBV co-infection, renal failure, history of liver transplantation, and history of DAA treatment failure.

The main characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | Year | Country | Main clinical characteristics of the patients | Resistance-associated substitutions | Mean age | Sex (male/ female) | Mean HCV RNA at baseline (log10 IU/mL) | No. of patients | Regimen and dosage | Treatment duration (weeks) | SVR12/24 (n) | Virologic failurea(n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarwar et al. [3] | 2019 | Pakistan | treatment experienced or with advanced fibrosis added RBV; with cirrhosis for 24 weeks; 58.4% with cirrhosis; 27.4% treatment experienced | NA | NA | NA | 6.34 | 113 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 102 | NA |

| Pariente et al. [4] | 2019 | France | 59.0% with cirrhosis | NA | NA | NA | NA | 117 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 103 | NA |

| Mangia et al. [5] | 2019 | Italy | all with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, 54.1% transient elastography results >20KPa; 72.8% treatment naïve; 5.3% with HCC; 9.8% HIV positive; 14.6% past intravenous drug use; 18.5% alcohol abuse; 17.6% with diabetes | NA | 52.9 | 175/30 | 2.53±4.3 | 205 | SOF (400mg)+VEL (100mg) | 12 | 200 | 5 relapses |

| Macken et al. [6] | 2019 | England | 91% with cirrhosis, 63.3% treatment naive | NA | NA | NA | NA | 256 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12 | 216 | |

| Lobato et al. [7] | 2019 | Brazil | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 817 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg) | 12-24 | 736 | NA |

| Llaneras et al. [8] | 2019 | Spain | all received a DAA-based interferon-free regimen: SOF and DCV or VEL or LDV; 43.3% with cirrhosis | of 6 relapses 1 detected with L28S, M31L and D168G, 1 with Y93H, 2 not detected, 2 NA | NA | NA | NA | 30 | SOF (400mg)+VEL (100mg)+VOX (100mg) | 12 | 24 | 6 relapses |

| Hlaing et al. [9] | 2019 | Myanmar | 6.16% treatment experienced; 67.6% with cirrhosis or advanced fibrosis | NA | NA | NA | NA | 193 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 187 | 6 relapses |

| 83 | SOF (400mg)+VEL (100mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 75 | 8 relapses | ||||||||

| Han et al. [10] | 2019 | China | 62.5% with history of drug abuse; 25% with compensated cirrhosis; 9.4% renal impairment; 96.9% treatment naive | NA | 44.26 | 26/6 | 5.91 | 32 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 31 | 1 relapse |

| Goel et al. [11] | 2019 | India | all eGFR<30ml/min, 18.2% with cirrhosis; | NA | NA | NA | NA | 22 | SOF (200mg)+DCV (60mg) | 12 | 19 | 0 |

| Degasperi et al. [12] | 2019 | Italy | all with a prior DAA failure: SOF and VEL or LDV, or OBV/PTV-r+DSV | of 3 relapses 1 detected with Y93H, 2 NA | NA | NA | NA | 42 | SOF (400mg)+VEL (100mg)+VOX (100mg)±RBV | 12 | 33 | 3 relapses |

| D'Ambrosio et al. [13] | 2019 | Italy | NA | of 2 relapses 1 detected with Y93H and L31I | NA | NA | NA | 68 | GLE (300mg)+PIB (120mg) | 8-16 | 66 | 2 relapses |

| Butt et al. [14] | 2019 | Pakistan | 84.2% treatment naïve, 52.5% with cirrhosis, | NA | 47.06 | 33/68 | NA | 101 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 24 | 96 | NA |

| Berg et al. [15] | 2019 | Germany | 8 weeks for treatment-naïve and non-cirrhotic patients, 12 weeks for treatment-naïve and cirrhotic patients, 16 weeks for treatment-experienced patients | NA | NA | NA | NA | 176 | GLE (300mg)+PIB (120mg) | 8-16 | 174 | NA |

| Belperio et al. [16] | 2019 | USA | 42.1% with cirrhosis, 3.03% with HCC, 22.9% treatment experienced | NA | 58.95 | 868/23 | 6.05 | 891 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-16 | 796 | NA |

| 26.5% with cirrhosis, 2.42% with HCC, 9.7% treatment experienced | 58.95 | 1662/73 | 6.05 | 1735 | SOF (400mg)+VEL (100mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 1573 | NA | ||||

| Belperio et al. [17] | 2019 | USA | all treatment experienced: SOF and DCV or VEL or LDV, 51.1% with cirrhosis, 4.44% with HCC, 2.22% with HIV coinfected, 37.8% with diabetes | NA | 59.7 | 51/0 | 6.1 | 45 | SOF (400mg)+VEL (100mg)+VOX (100mg) | 12 | 42 | NA |

| Araujo et al. [18] | 2019 | Brazil | 6.5% with cirrhosis | NA | NA | NA | NA | 31 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg) | 12 | 30 | 1 virologic failure |

| Wehmeyer et al. [19] | 2018 | Germany | 28.75% treatment experienced, 33.75% with cirrhosis, 15% with HIV coinfected | NA | NA | NA | NA | 80 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 76 | NA |

| Felden et al. [20] | 2018 | Germany | 24.8% treatment experienced, 26.6% with cirrhosis, 8.56% with HIV coinfected | 22 patients with baseline NS5A RASs (Y93H, A30K or L31M) | NA | NA | NA | 222 | SOF (400mg)+VEL (100mg)±RBV | 12 | 213 | NA |

| Tao et al. [21] | 2018 | China | 34.6% with cirrhosis | NA | 41.71 | 48/33 | 6.30 | 81 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 71 | 10 relapses |

| 23.8% with cirrhosis | 37.38 | 13/8 | 6.04 | 21 | SOF (400mg)+VEL (100mg) | 12-24 | 21 | 0 | ||||

| Mucenic et al. [22] | 2018 | Brazil | all liver transplant recipients | NA | NA | NA | NA | 26 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12 | 22 | 2 relapses and 2 non-responses |

| Minguez et al. [23] | 2018 | Spain | all HIV-coinfected | NA | NA | NA | NA | 53 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12 | 48 | |

| Mehta et al. [24] | 2018 | India | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 372 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 362 | 5 non-responses, 2 breakthroughs, and 10 relapses |

| Marciano et al. [25] | 2018 | Argentina | 89.4% with cirrhosis, | NA | NA | NA | NA | 47 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 24 | 38 | NA |

| Lim et al. [26] | 2018 | India, Myanmar, Pakistan, Thailand, Singapore, and Malaysia | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 310 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 282 | 6 |

| Kwo et al. [27] | 2018 | USA | 64% liver transplant, 36% with decompensated cirrhosis | NA | NA | NA | NA | 25 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 24 | 22 | 1 breakthrough |

| Rockstroh et al. [28] | 2017 | Germany | all HIV-coinfected and with an advanced stage of cirrhosis | NA | NA | NA | NA | 13 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 24 | 12 | NA |

| Lacombe et al. [29] | 2017 | France | all HIV-coinfected and with advanced liver disease | NA | NA | NA | NA | 47 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 42 | 2 relapses and 1 undefined virologic failure |

| Hezode et al. [30] | 2017 | France | 76.9% with cirrhosis, 8.1% with HCC, 9.0% post-liver transplant HCV recurrence, 9.0% pre-liver/renal transplant, 71.2% treatment experienced, 14.1% HIV-coinfected, 2.1% HBV-coinfected | NA | 54.2 | 245/88 | 6.0 | 333 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 278 | 4 breakthroughs, 32 relapses, and 9 undefined |

| Dalgard et al. [31] | 2017 | Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland | 51.8% treatment experienced, 73.2% with cirrhosis | NA | 56 | 135/60 | NA | 193 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 177 | NA |

| Cornberg et al. [32] | 2017 | Germany | 32.7% with cirrhosis, 29.1% treatment experienced | NA | NA | NA | NA | 220 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 207 | NA |

| Gray et al. [33] | 2017 | Ireland | 28.9% treatment experienced | NA | NA | NA | NA | 76 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 24 | 67 | 0 |

| Sette-Jr et al. [34] | 2017 | Brazil | 35.7% with cirrhosis | of 4 relapses 2 detected with Y93H, 2 not done | NA | NA | NA | 28 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 24 | 4 relapses |

| Alonso et al. [35] | 2017 | Spain | 26% with decompensated cirrhosis, 45% treatment experienced | NA | 55 | 110/21 | 6.0 | 131 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 12-24 | 123 | 6 relapses, 1 breakthrough |

| Welzel et al. [36] | 2016 | Germany, Austria, Netherlands, Sweden, and Norway | 84.9% with cirrhosis, 60.2% treatment experienced | NA | NA | NA | NA | 93 | SOF (400mg)+DCV (60mg)±RBV | 24 | 82 | NA |

NA: Data not available for HCV GT3-infected patients; DSV: Dasabuvir; LDV: Ledipasvir; OBV/PTV-r: Ombitasvir/paritaprevir-ritonavir; VEL: Velpatasvir.

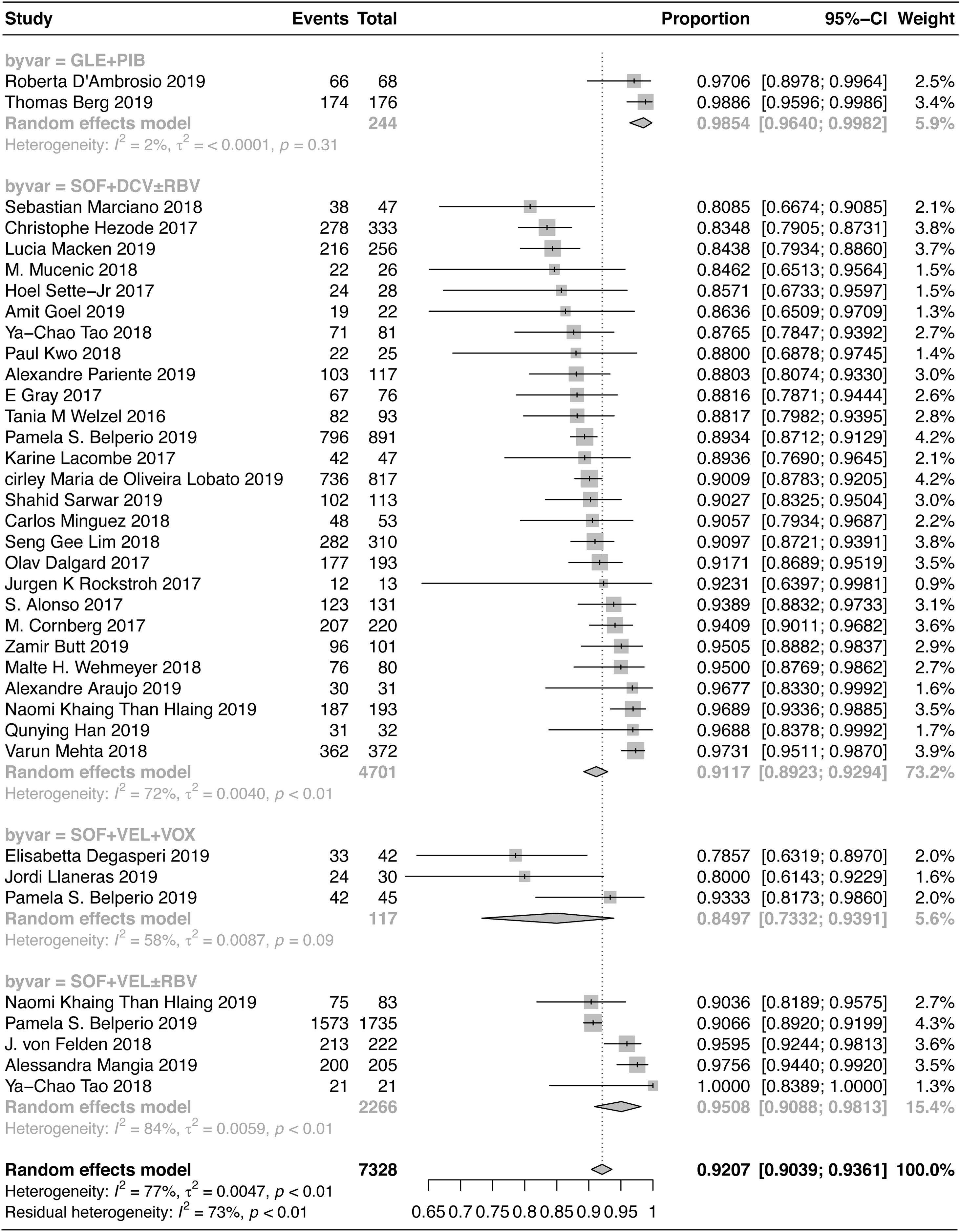

A total of 7328 patients with HCV-GT3 infection were treated with SOF+VEL+VOX, SOF+DCV±RBV, SOF+VEL±RBV, and GLE+PIB. The pooled SVR12/24 rate was 92.07% (95% CI: 90.39–93.61%), as shown in Fig. 2. The SVR12/24 rate was 84.97% (95% CI: 73.32–93.91%) in patients treated with SOF+VEL+VOX; 91.17% (95% CI: 89.23–92.94%) in patients treated with SOF+DCV±RBV; 95.08% (95% CI: 90.88–98.13%) in patients treated with SOF+VEL±RBV; and 98.54% (95% CI: 96.40–99.82%) in patients treated with GLE+PIB.

The results of Chi-square test indicated a significant difference in the SVR of four treatment regimens (P<0.001). The two-by-two comparisons showed that GLE+PIB was superior to the other three regimens. The SOF+VEL±RBV regimen was superior to SOF+VEL+VOX, which could be related to the selection of populations with a history of DAA (SOF+VEL or LDV or DCV or OBV/PTV-r+DSV) treatment failure in the SOF+VEL+VOX group. However, there was no significant difference between SOF+DCV±RBV and SOF+VEL±RBV or between SOF+DCV±RBV and SOF+VEL+VOX.

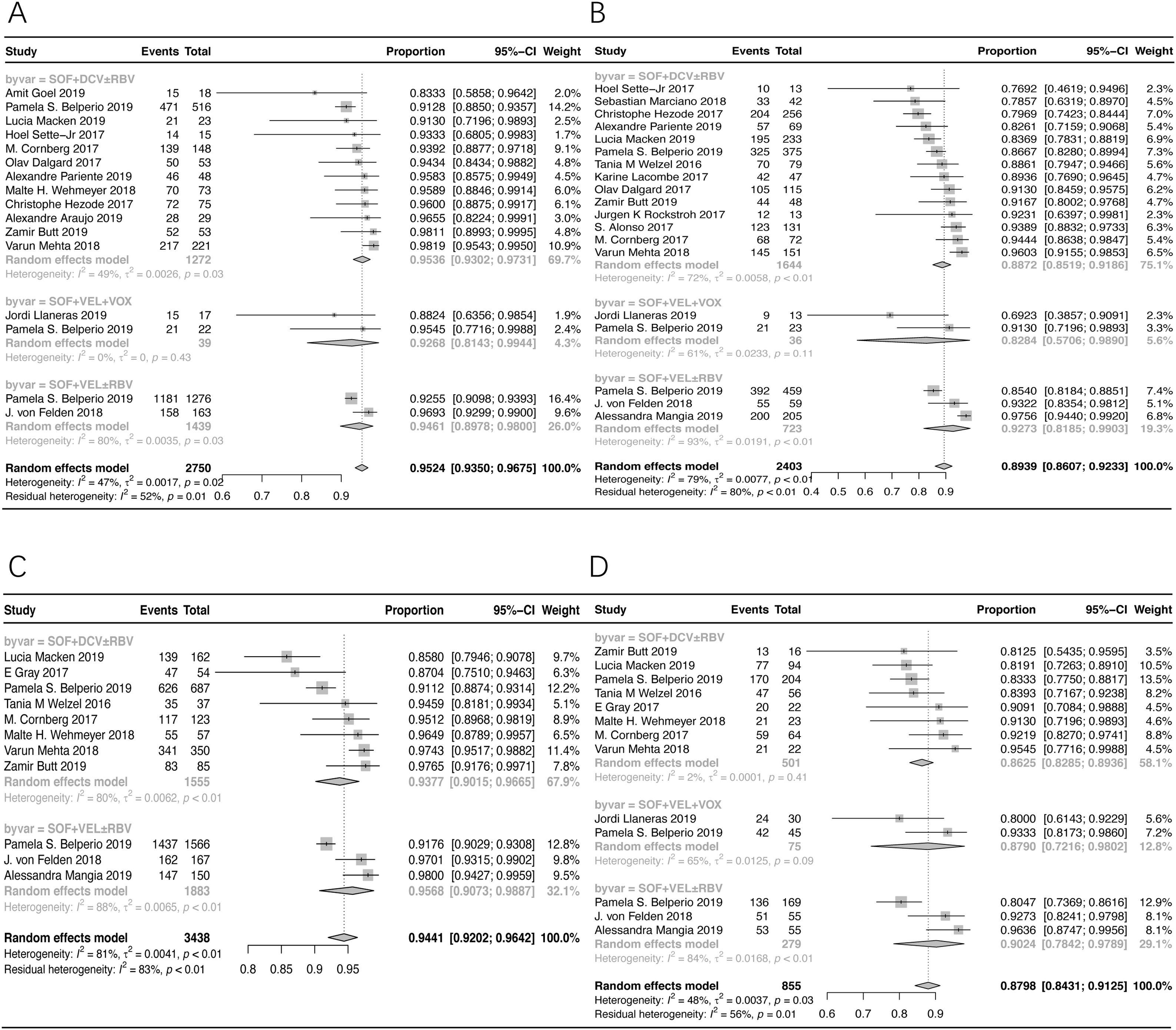

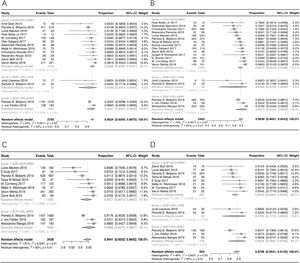

3.3Stratification analysis (non-cirrhotic patients)According to the subgroup analysis of non-cirrhotic patients, the pooled SVR12/24 rate was 95.24% (95% CI: 93.50–96.75%) in patients treated with SOF+DCV±RBV, SOF+VEL+VOX, and SOF+VEL±RBV, as shown in Fig. 3A. The SVR12/24 rate was 95.36% (95% CI: 93.02–97.31%) in patients treated with SOF+DCV±RBV; and 94.61% (95% CI: 89.78–98.00%) in patients treated with SOF+VEL±RBV.

The forest plots of stratification analysis. (A) The forest plots of SVR rates in non-cirrhotic patients. (B) The forest plots of SVR rates in cirrhotic patients. (C) The forest plots of SVR rates in treatment-naive patients. (D) The forest plots of SVR rates in treatment-experienced patients.

The pooled SVR12/24 rate was 89.39% (95% CI: 86.07–92.33%) in cirrhotic patients treated with SOF+DCV±RBV, SOF+VEL+VOX, and SOF+VEL±RBV, as shown in Fig. 3B. Based on the results, the SVR12/24 rate was 88.72% (95% CI: 85.19–91.86%) in patients treated with SOF+DCV±RBV; and 92.73% (95% CI: 81.85–99.03%) in patients treated with SOF+VEL±RBV.

3.5Stratification analysis (treatment-naive patients)According to the subgroup analysis of treatment-naive patients, the pooled SVR12/24 rate in patients treated with SOF+DCV±RBV and SOF+VEL±RBV was 94.41% (95% CI: 92.02–96.42%), as shown in Fig. 3C. Also, the SVR rates in patients treated with SOF+DCV±RBV and SOF+VEL±RBV were 93.77% (95% CI: 90.15–96.65%) and 95.68% (95% CI: 90.73–98.87%), respectively.

3.6Stratification analysis (treatment-experienced patients)The pooled SVR12/24 rate of treatment-experienced patients with HCV-GT3 infection, treated with SOF+VEL+VOX, SOF+VEL±RBV, and SOF+DCV±RBV, was 87.98% (95% CI: 84.31–91.25%), as shown in Fig. 3D. Also, the corresponding SVR12/24 rates were 87.90% (95% CI: 72.16–98.02%), 90.24% (95% CI: 78.42–97.89%), and 86.25% (95% CI: 82.85–89.36%), respectively.

3.7Sensitivity analysis of heterogeneityChanges in the results of sensitivity analysis ranged from 91.75% to 92.39% after excluding articles one by one, which is a very small range, indicating stable results.

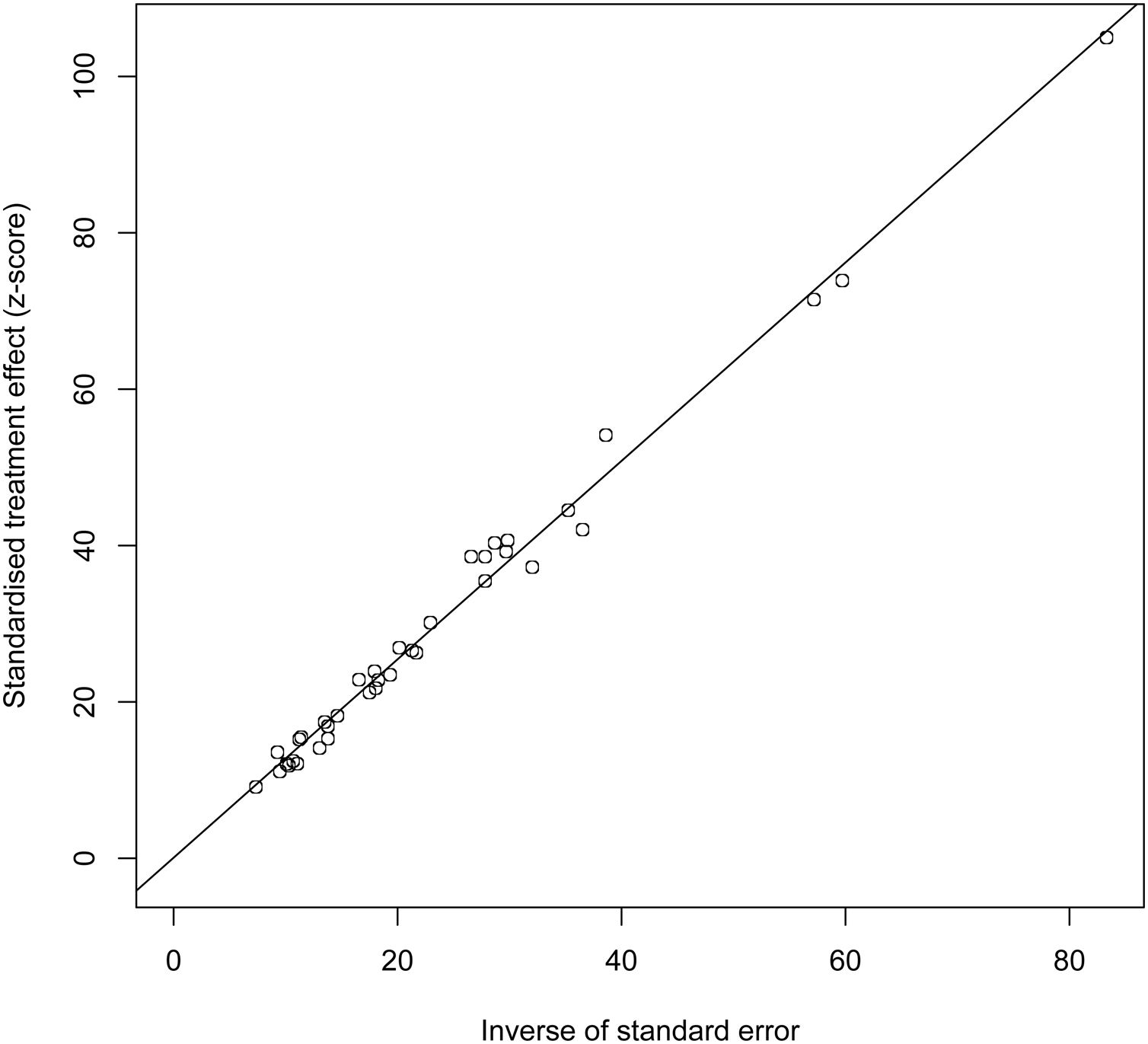

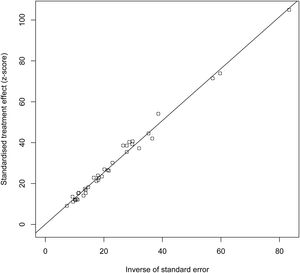

3.8Publication biasThe results of Egger’s test indicated no publication bias (t=0.12404, DF=35, P=0.902), as shown in Fig. 4.

4DiscussionIn this review, the majority of treatment regimens in real-world studies included SOF+DCV±RBV, which accounted for 73% of treatments. The SOF+DCV±RBV regimen was the first-line therapeutic regimen for all HCV genotypes, as recommended by the FDA and EMA. In our meta-analysis, the pooled SVR12/24 was 91.17% in HCV GT3-infected patients. The SVR rates of cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients were 88.72% and 95.36%, respectively. Also, the SVR rates of treatment-experienced and treatment-naive patients were 86.25% and 93.77%, respectively.

The cirrhosis stage and history of treatment had significant effects on the antiviral effectiveness. In this regard, a phase III clinical study (ALLY-3) [37] showed that the pooled SVR12 rate of HCV GT3-infected patients, treated with SOF+DCV, was 89%, of which there was 63% in patients with cirrhosis and 96% in patients without cirrhosis; therefore, the SOF+DCV regimen was not suitable for cirrhotic and treatment-experienced patients with HCV-GT3 infection. Also, Amit Goel et al. [11] evaluated patients with renal insufficiency (eGFR<30ml/min), treated with SOF (200mg per day), and reported an SVR12 rate of 86.36%. Moreover, Mucenic et al. [22] selected patients with virologic relapse following liver transplantation and reported an SVR12 rate of 84.62%. Also, Carlos Minguez [23], Jurgen K Rockstroh [28], and Karine Lacombe [29] in studies on HIV co-infected patients reported SVR rates of 90.57%, 92.31%, and 89.36%, respectively. Compared to renal insufficiency and virologic relapse following liver transplantation, the effect of HIV co-infection on the antiviral effectiveness of SOF+DCV±RBV was relatively less significant.

The SOF+VEL±RBV regimen, approved in 2017, is the first treatment regimen, which can be used for 12 weeks, regardless of HCV genotype and liver fibrosis stage. In the present study, the SVR rate of patients with HCV-GT3 infection was 95.08%, which is higher than that of SOF+DCV±RBV. The SVR rates of cirrhotic, non-cirrhotic, treatment-naive, and treatment-experienced patients, treated with SOF+VEL±RBV, were 92.73%, 94.61%, 95.68%, and 90.24%, respectively. The effect of treatment history on the antiviral effectiveness of SOF+VEL±RBV was more significant than that of cirrhosis stage.

Belperio et al [16] gained the similar SVR rates of the GT3 HCV patients treated with SOF+VEL±RBV compared with SOF+DCV±RBV. In this meta-analysis the pooled SVR rate of SOF+VEL±RBV was a little higher (95.08%) than that of SOF+DCV±RBV (91.17%). This may be associated with the high SVR rate (100%, 21/21) from Tao’s study [21]. In non-cirrhotic patients, the SVR rates of the two regimens were almost the same (94.61% for SOF+VEL±RBV and 95.36% for SOF+DCV±RBV). However, in patients with cirrhosis, the SVR rate of SOF+VEL±RBV was higher than that of SOF+DCV±RBV (92.73% and 88.72%, respectively). Also, in cirrhotic patients, the SOF+VEL±RBV regimen was found to be more suitable than SOF+DCV±RBV.

The GLE+PIB regimen was approved by the FDA and EMA, regardless of HCV genotypes. This regimen decreases the treatment duration to eight weeks for hepatitis and compensated cirrhotic patients. It can be also used for patients with renal dysfunction or even those undergoing dialysis. In a phase-III clinical study (ENDURANCE-3) [38] on patients treated with GLE+PIB for 8 or 12 weeks, the SVR rate was 95% in treatment-naive hepatitis patients with HCV-GT3 infection. Also, in the SURVEYOR-II Part-3 study [39], the SVR rate of HCV GT3-infected patients was 91% after 12 weeks of treatment; the patients were either treatment-naive or treatment-experienced, with or without cirrhosis. Moreover, in the EXPEDITION-2,4 studies [40,41], the SVR rate was 98% in patients after 8-12 weeks of treatment. In this real-world meta-analysis, the SVR rate of patients with HCV-GT3 infection, treated with GLE+PIB, could reach 97% or higher.

Our meta-analysis showed that the SVR rate of SOF+VEL+VOX was 84.97%, which is lower than that of SOF+DCV±RBV, SOF+VEL±RBV, and GLE+PIB; this result may be related to previous resistance to DAA (SOF+VEL or LDV or DCV or OBV/PTV-r+DSV) in patients treated with SOF+VEL+VOX. The SOF+VEL+VOX regimen, which included a combination of three DAAs, was mainly designed as a treatment plan for patients with a history of DAA treatment failure. In this regard, the POLARIS-3 study [42] evaluated patients with liver cirrhosis, who were initially treated with DAAs. After eight weeks of treatment with SOF+VEL+VOX, the SVR rate of patients with HCV-GT3 infection reached 96% (106/110).

Moreover, in the POLARIS-1 study [43], the SVR rate of patients with HCV-GT3 infection was 95% (74/78) after 12 weeks of treatment. In this paper, some real-world studies [8,12,17] on patients with a history of DAA treatment failure reported SVR rates of 80.00%, 78.57%, and 93.33%, respectively. The antiviral effectiveness of SOF+VEL+VOX in real-word studies was lower than that of registered clinical studies in patients with a history of DAA treatment failure. Also, in two real-word studies [8,12], the number of patients with virologic relapse was 6/30 and 3/42 during the follow-up, respectively.

In real-world studies, the SVR rate of SOF+VEL+VOX was low in HCV GT3-infected patients with a history of DAA treatment failure, and the possibility of virologic relapse was still high. Overall, HCV-GT3 infection in patients with a history of DAA treatment failure poses challenges for the current antiviral treatments. In the present study, the pooled SVR rate of the four antiviral regimens for HCV-GT3 infection was 92.07%. The SVR rate of GLE+PIB was the highest (98.54%), and the treatment duration was the shortest (possibly eight weeks).

Clinical trials [37,44] reported that patients with the presence of baseline RASs (Y93H and A30K) in the NS5A gene had lower SVR rates, which was associated with decreased in vitro activity of DCV and VEL. In the ASTRAL-3 study [45], 84% SVR in the presence of Y93H compared to 97% in patients without Y93H was achieved from patients treated with SOF/VEL. However, in this meta-analysis only 6 articles completed RAVs test. It is interesting that all the 6 studies [8,12,13,17,20,34] draw a conclusion that RASs may be not associated with lower SVR rate. High SVR rates in patients completing therapy suggested that pretreatment RAS testing may not be necessary.

This meta-analysis has limitations. We think that no strong conclusions can be drawn due to high heterogeneity in four DAA regimens administration in real-world setting from 22 countries, as well as small numbers of patients treated with SOF+VEL+VOX and GLE+PIB. More studies are needed in the future in order to better analyze the antiviral effectiveness of DAAs in GT3 HCV patients in real-world studies.

5ConclusionAccording to our meta-analysis of real-world studies, the antiviral effectiveness of treatment regimens for HCV-GT3 infection, including SOF+DCV±RBV, SOF+VEL±RBV, GLE+PIB, and SOF+VEL+VOX, was good. The SVR rate of GLE+PIB was higher, and the treatment duration was shorter than other regimens. Based on the findings, SOF+VEL+VOX can be used as a treatment regimen following DAA treatment failure. Also, a history of DAA treatment failure still poses challenges for current treatments.

FundingThis study was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project of China under Gran [grant number 2018ZX10302-206-003-006]; the Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research [grant number CFH 2020-1-2171 and CFH 2018-2-2173]; the Beijing Hospitals Authority Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding [grant number XMLX201837]; the Digestive Medical Coordinated Development Center of Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals [grant number XXT26].

Conflict of interestAll authors had approved the final version of the manuscript for publication and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The authors have read the journal's policy on conflicts of interest and they declare that they have no competing interest.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Liwei Zhuang, and Huichun Xing; initial article screen: Shibo Ji, Yue Li, Ben Li, Ying Duan, Danying Cheng, Yu Zhang, Min Quan, Hong Zhao and Wei Li; finial article screen: Liwei Zhuang, and Yu Zhang; analysis and interpretation of data: Liwei Zhuang, Junnan Li, Yu Zhang, and Huichun Xing; drafting of the manuscript: Liwei Zhuang; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Xiaomei Wang, Weini Ou, and Huichun Xing; statistical analysis: Liwei Zhuang, Junnan Li and Huichun Xing.