Hepatitis E (HEV) is a common infection worldwide and is an emerging disease in developed countries. The presence of extra-hepatic manifestation of HEV infection is important to bear in mind so that the diagnosis is not missed, since HEV is not routinely tested for in acute hepatitis due to perceived rarity of this infection outside of endemic countries. This article reviews the neurological presentations of acute and chronic HEV, and discusses the viral kinetics against symptomatology, and outcomes of specific treatment. Possible mechanisms of pathogenesis are considered.

Hepatitis E (HEV) is an under-diagnosed infection in developed countries, with the potential to cause significant morbidity as well as mortality.1,2 The actual incidence of local HEV in developed countries is uncertain, especially as subclinical infection is common.1

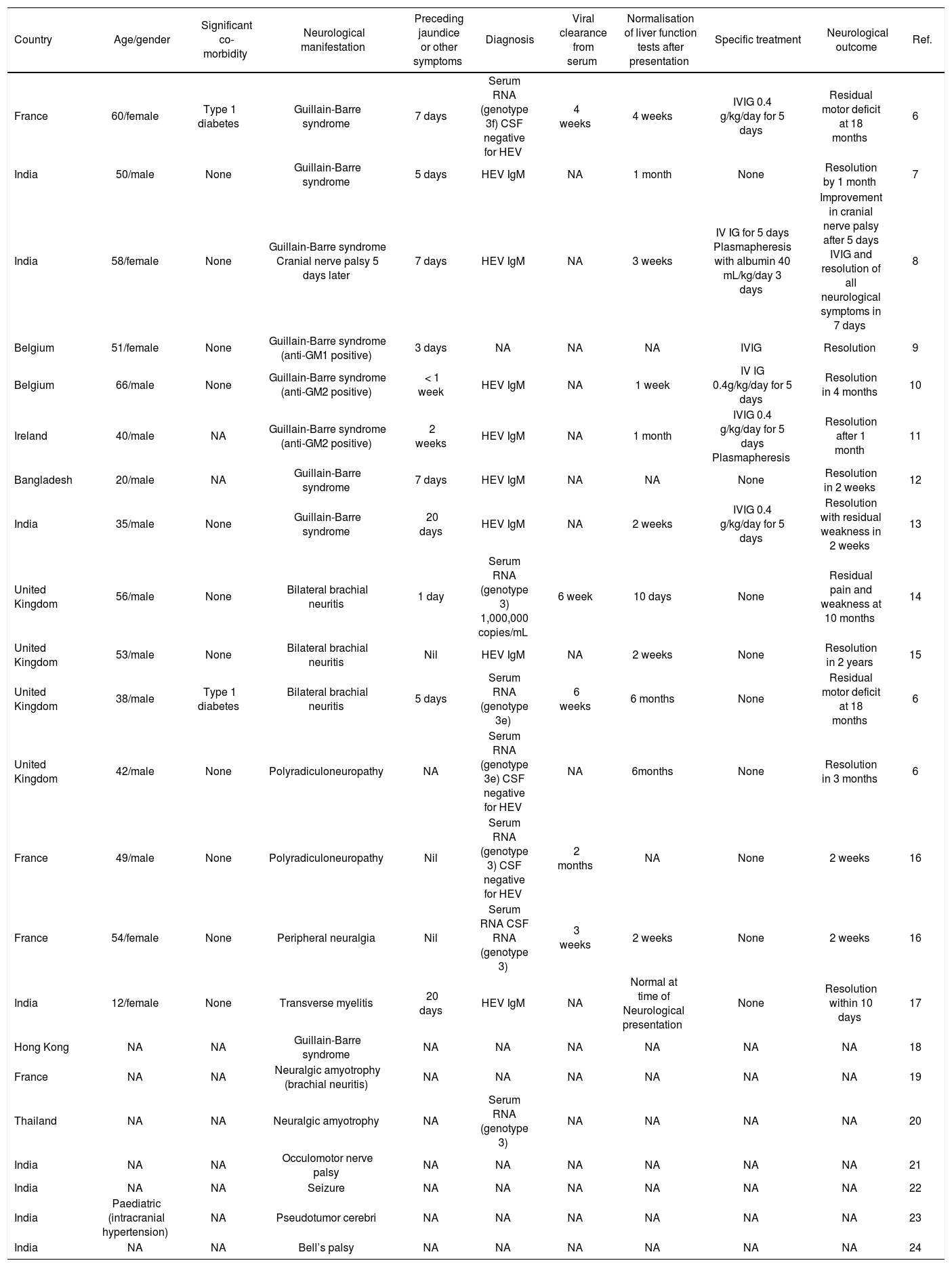

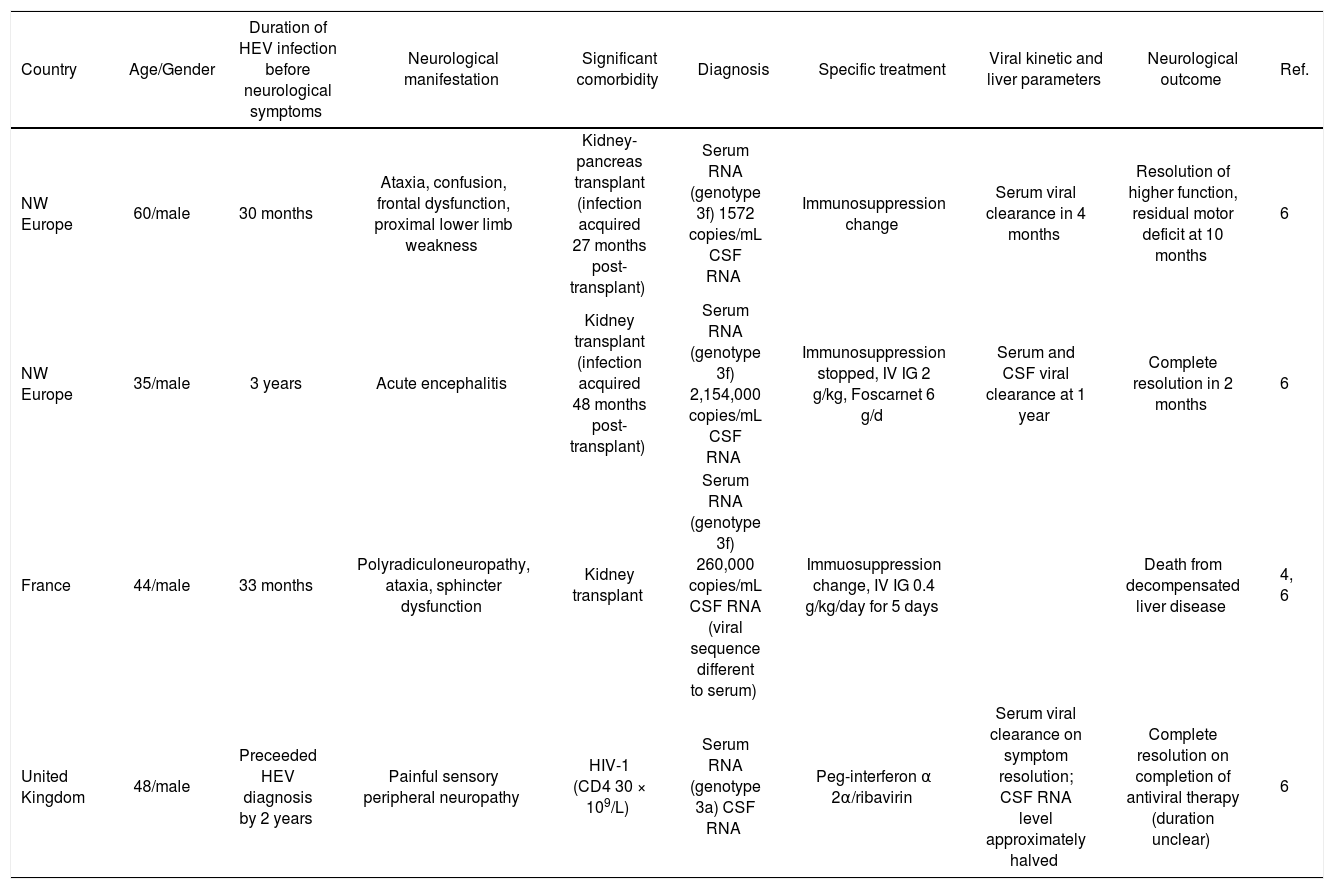

Clinical manifestations of HEV typically include jaundice, fever, malaise, abdominal pain and vomiting, lasting 2 to 18 weeks with a median of 4 weeks.1 As with other viral hepatitises, extra-hepatic manifestations can occur,3 and the spectrum of clinical disorders is still emerging.4-6 In particular, neurological disorders with a predominance of peripheral nerve disorders have been described.6 A literature review found 25 cases reporting neurological manifestations of HEV in both acute and chronic infections 4,6-24 (Tables 1 and 2). Guillain-Barre syndrome and brachial neuritis are most frequently reported. Other reported disorders include transverse myelitis, cranial nerve palsies, seizure and intracranial hypertension. 17,21-24

Summary of acute hepatitis E with neurological manifestation.

| Country | Age/gender | Significant co-morbidity | Neurological manifestation | Preceding jaundice or other symptoms | Diagnosis | Viral clearance from serum | Normalisation of liver function tests after presentation | Specific treatment | Neurological outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | 60/female | Type 1 diabetes | Guillain-Barre syndrome | 7 days | Serum RNA (genotype 3f) CSF negative for HEV | 4 weeks | 4 weeks | IVIG 0.4 g/kg/day for 5 days | Residual motor deficit at 18 months | 6 |

| India | 50/male | None | Guillain-Barre syndrome | 5 days | HEV IgM | NA | 1 month | None | Resolution by 1 month | 7 |

| India | 58/female | None | Guillain-Barre syndrome Cranial nerve palsy 5 days later | 7 days | HEV IgM | NA | 3 weeks | IV IG for 5 days Plasmapheresis with albumin 40 mL/kg/day 3 days | Improvement in cranial nerve palsy after 5 days IVIG and resolution of all neurological symptoms in 7 days | 8 |

| Belgium | 51/female | None | Guillain-Barre syndrome (anti-GM1 positive) | 3 days | NA | NA | NA | IVIG | Resolution | 9 |

| Belgium | 66/male | None | Guillain-Barre syndrome (anti-GM2 positive) | < 1 week | HEV IgM | NA | 1 week | IV IG 0.4g/kg/day for 5 days | Resolution in 4 months | 10 |

| Ireland | 40/male | NA | Guillain-Barre syndrome (anti-GM2 positive) | 2 weeks | HEV IgM | NA | 1 month | IVIG 0.4 g/kg/day for 5 days Plasmapheresis | Resolution after 1 month | 11 |

| Bangladesh | 20/male | NA | Guillain-Barre syndrome | 7 days | HEV IgM | NA | NA | None | Resolution in 2 weeks | 12 |

| India | 35/male | None | Guillain-Barre syndrome | 20 days | HEV IgM | NA | 2 weeks | IVIG 0.4 g/kg/day for 5 days | Resolution with residual weakness in 2 weeks | 13 |

| United Kingdom | 56/male | None | Bilateral brachial neuritis | 1 day | Serum RNA (genotype 3) 1,000,000 copies/mL | 6 week | 10 days | None | Residual pain and weakness at 10 months | 14 |

| United Kingdom | 53/male | None | Bilateral brachial neuritis | Nil | HEV IgM | NA | 2 weeks | None | Resolution in 2 years | 15 |

| United Kingdom | 38/male | Type 1 diabetes | Bilateral brachial neuritis | 5 days | Serum RNA (genotype 3e) | 6 weeks | 6 months | None | Residual motor deficit at 18 months | 6 |

| United Kingdom | 42/male | None | Polyradiculoneuropathy | NA | Serum RNA (genotype 3e) CSF negative for HEV | NA | 6months | None | Resolution in 3 months | 6 |

| France | 49/male | None | Polyradiculoneuropathy | Nil | Serum RNA (genotype 3) CSF negative for HEV | 2 months | NA | None | 2 weeks | 16 |

| France | 54/female | None | Peripheral neuralgia | Nil | Serum RNA CSF RNA (genotype 3) | 3 weeks | 2 weeks | None | 2 weeks | 16 |

| India | 12/female | None | Transverse myelitis | 20 days | HEV IgM | NA | Normal at time of Neurological presentation | None | Resolution within 10 days | 17 |

| Hong Kong | NA | NA | Guillain-Barre syndrome | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 18 |

| France | NA | NA | Neuralgic amyotrophy (brachial neuritis) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 19 |

| Thailand | NA | NA | Neuralgic amyotrophy | NA | Serum RNA (genotype 3) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 20 |

| India | NA | NA | Occulomotor nerve palsy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 21 |

| India | NA | NA | Seizure | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 22 |

| India | Paediatric (intracranial hypertension) | NA | Pseudotumor cerebri | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 23 |

| India | NA | NA | Bell’s palsy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 24 |

IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin. CSF: cerebrospinal fluid.

Summary of chronic hepatitis E with neurological manifestation.

| Country | Age/Gender | Duration of HEV infection before neurological symptoms | Neurological manifestation | Significant comorbidity | Diagnosis | Specific treatment | Viral kinetic and liver parameters | Neurological outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NW Europe | 60/male | 30 months | Ataxia, confusion, frontal dysfunction, proximal lower limb weakness | Kidney-pancreas transplant (infection acquired 27 months post-transplant) | Serum RNA (genotype 3f) 1572 copies/mL CSF RNA | Immunosuppression change | Serum viral clearance in 4 months | Resolution of higher function, residual motor deficit at 10 months | 6 |

| NW Europe | 35/male | 3 years | Acute encephalitis | Kidney transplant (infection acquired 48 months post-transplant) | Serum RNA (genotype 3f) 2,154,000 copies/mL CSF RNA | Immunosuppression stopped, IV IG 2 g/kg, Foscarnet 6 g/d | Serum and CSF viral clearance at 1 year | Complete resolution in 2 months | 6 |

| France | 44/male | 33 months | Polyradiculoneuropathy, ataxia, sphincter dysfunction | Kidney transplant | Serum RNA (genotype 3f) 260,000 copies/mL CSF RNA (viral sequence different to serum) | Immuosuppression change, IV IG 0.4 g/kg/day for 5 days | Death from decompensated liver disease | 4, 6 | |

| United Kingdom | 48/male | Preceeded HEV diagnosis by 2 years | Painful sensory peripheral neuropathy | HIV-1 (CD4 30 × 109/L) | Serum RNA (genotype 3a) CSF RNA | Peg-interferon α 2α/ribavirin | Serum viral clearance on symptom resolution; CSF RNA level approximately halved | Complete resolution on completion of antiviral therapy (duration unclear) | 6 |

IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin. CSF = cerebrospinal fluid.

Neurological disease occurred in sporadic and endemic infection within this cohort. Most case reports come from developing countries, reflecting the geographical distribution of HEV. All genotyped cases showed genotype 3 infection, which is found in developed countries. Cases from the Indian subcontinent are likely to be genotype 1.

A recent case series from Southwest England and Toulouse found a 5.5% prevalence (7 out of 126 over five years) of neurological complications in locally-acquired HEV infections.6 Most of the reported cases of acute HEV were evidenced only by positive serology (anti-HEV IgM), which persists after viral clearance and therefore does not indicate duration of infection.1 However the temporal relationship between development of transaminitis and neurological symptoms with evidence of HEV infection, and exclusion of other hepatotrophic causes, suggest this association is causal. Moreover, the presence of similar cases which were confirmed by RNA isolation substantiates a true association between HEV infection and neurological disorders.

Acute HEV infection is self-limiting. In cases of Guillain-Barre, where intravenous immunoglobulin and plasma exchange both have established effectiveness,25 its use was associated with complete resolution of symptoms, but benefit over supportive treatment cannot be concluded. Cases of brachial neuritis were comparatively slower to resolve and none received specific therapies.

Severity of HEV infection is related to viral load 1 but the number of cases with established level of viraemia is too small to ascertain if HEV has a dose effect on neurological symptoms and outcomes. There is no clear correlation between viral clearance, liver enzyme tests and duration of neurological symptoms.

Four reports exist of neurological symptoms in chronic HEV in immunosuppressed patients following organ transplant or HIV infection.4,6 The temporal relationship between viral kinetics and symptom onset and resolution is variable in chronic HEV. The duration of infection before onset of neurological symptoms ranged from 18 months to 3 years. Chronic infection was evidenced by liver biopsy showing chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis and detection of RNA; serology in these patients may be unreliable. Demonstration of HEV RNA in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) may account for involvement of the central nervous system, however, two patients with virus in CSF did not display disturbance of higher functions. Development of liver cirrhosis and decompensation are potential confounding factors. Despierres, et al. suggested the presence of HEV in the CSF may be related serum viral load,16 but in Kamar's case there was low serum viral low but detectable virus in CSF and marked central nervous system disturbance (60). Therefore this is insufficient explanation for the selective occurrence of central nervous system symptoms.

There is no established treatment for chronic HEV; lowering of immunosuppression therapy is recommended26 and pegylated interferon alpha has been used successfully in liver transplants.26,27 In one case the use of pegylated interferon alpha with ribavarin resulted in viral clearance and neurological symptom resolution.6

Several mechanisms of HEV causing neurological disease have been proposed. In neuropathies following infections such as Guillain-Barre syndrome after Campylobacter, influenza and cytome-galovirus, anti-ganglioside antibodies are thought to play a pathogenic role.28 Anti-ganglioside antibodies were positive in 3 out of 6 cases of HEV-GBS where they were measured, with one case of GM1 antibody and remainder of GM2.9-11 Their production may be triggered by HEV infection which in turn leads to autoimmune inflammatory polyneuropathy via molecular mimicry. Treatment with immunoglobulin targets the autoimmune nature of GBS but due to the small number of HEV-associated cases, it is difficult to comment on treatment response.

Brachial neuritis is also thought to be autoimmune in origin in genetically susceptible individuals. 29 More than half of patients develop an immune event preceding neurological symptoms, such as viral infections (HIV, coxsackie, EBV), vaccination and pregnancy.29 HEV may cause brachial neuritis by precipitating such an autoimmune response.

The isolation of different viral sequences within CSF and serum of the same patient suggest the possible emergence of neurotropic quasispecies which can directly affect the nervous system.4,6 However in acute infection which can resolve within days, this mechanism is less probable.

The pathogenesis of HEV causing peripheral neuropathy and other neurological disorders may involve multiple mechanisms, predisposing and host immune factors, to account for the variety in manifestations, but the small number of cases and distribution in developing countries makes further investigations difficult.

ConclusionHepatitis E infection has well-documented neurological manifestations which can lead to significant morbidity. The spectrum of disease is wide and natural history variable. Specific therapies targeting the potential autoimmune aetiology did not produce consistent responses in the few cases used. Clinicians are challenged with uncertainties in prognosis and management. Hepatitis E is increasingly seen in developed countries as locally-acquired infections, and should be tested for in acute hepatitis, especially in seronegative or suspected drug-related cases. In addition, HEV infection should be considered in neurological disturbance associated with abnormal liver function tests.

Conflict Of InterestStatement of conflicts of interests: none declared.

Statement of funding sources: none declared.