Due to virological, host and socio-economic factors, the clinical presentation and treatment of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) differs between developing and developed countries and may differ between one low-income country and another. National healthcare prevention and treatment policies, environmental factors, social habits and personal life-styles all influence HBV transmission and the clinical management and therapy of CHB. These factors can have a strong impact on the natural history of the disease and on access to treatment and may eventually determine substantial changes in disease progression and the development of serious complications and hepatocellular carcinoma. In this review article, we analyze the clinical characteristics and access to antiviral treatment of CHB patients in low-income countries in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America.

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection affects nearly 240 million people worldwide,1 with intermediate or high endemicity levels in low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe and Asia. In these areas, various political and socio-economic factors hamper the prevention and control of HBV infection and the correct follow-up and the most appropriate treatment of the disease. The data on the clinical presentation, course of the disease and treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) in low-income countries with an intermediate or high HBV endemicity (HBsAg sero-prevalence over 2%) will be presented and discussed in this review article.

Clinical Presentation of HBV InfectionHBV infection progresses to chronicity in 90% of newborn babies born of HBeAg-positive mothers, in 80-90% of infants infected during the first year of life,1 in 20-50% of children under 6, in 6% of those aged 5-15 years and in 1-5% of subjects in the older population.2 The clinical course of HBV infection varies from an asymptomatic, silent progression over decades to a rapid evolution to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).3–6

Several factors have been associated with the severity of CHB: virus-related factors (genotype, viral load, length of infection), co-morbidities (immunosuppression of different nature, co-infection with hepatitis delta virus, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus), host-related factors (immune response) and environmental factors (alcohol abuse).7–16 The majority of CHB patients remain asymptomatic for years until liver cirrhosis, an end-stage liver disease, or HCC develops.17 The factors associated with the development of HCC are male gender, an older age, the reversion from anti-HBe to HBeAg, being infected with HBV-genotype C, having a core promoter mutation, or the presence of cirrhosis.18–22 In CHB patients who acquired HBV infection at birth or in infancy, HBeAg positivity and high levels of HBV DNA have been identified as independent predictors of cirrhosis and HCC development.23–27 In western countries, HCC occurs in 2-3% of cirrhotic patients per year, but in developing countries with a high HBV endemicity it is more frequent and may even occur in CHB patients without cirrhosis.

TreatmentAnti-HBV treatment favorably modifies the natural history of chronic hepatitis B and reduces HBV replication and the rate of disease progression to liver cirrhosis, to an end-stage liver disease and most probably to HCC.28 Several drugs have been extensively used to treat this disease: standard and pegylated interferon (Peg-IFN), the nucleoside analogues (NUCs) lamivudine (LAM), telbivudine (LdT) and entecavir (ETV) and the nucleotide analogues, adefovir (ADV) and tenofovir (TDF).

Peg-IFN treatment is a finite treatment followed by a sustained response in 25-40% of cases, by anti-HBe seroconversion in 30% of HBeAg-positive patients and a longterm HBV suppression in nearly 20% of anti-HBe-positive patients.29,30

Lamivudine has been widely used to treat CHB, with an excellent antiviral action and relatively low cost. This drug, however, has a low genetic barrier and its long-term treatment is associated with a rate of viral resistance up to 70% of treated patients on a 5-year administration. In particular, the mutations conferring resistance to lamivudine occur in the highly conserved YMDD (Y: tyrosine; M: methionine; D: aspartic acid; D: aspartic acid) motif of the catalytic domain (C domain) of the polymerase. Several studies have reported that this mutation can also occur spontaneously.31–36 Although LAM has been extensively used for years37,38 and the addition of ADV in the case of LAM resistance has been demonstrated to be successful,39 the administration of ETV or TDF is recommended as a first-line treatment.29,40 These two drugs are highly effective in suppressing HBV replication, are safe even if administered for years and, due to their high genetic barrier, rarely induce viral resistance.41–43 Recently, ETV has been demonstrated to be superior to LAM in reducing the risk of death and liver transplantation, but not the risk of HCC development.44

Telbivudine is less effective than ETV and TDF because of its lower genetic barrier, particularly for patients with a high HBV-DNA serum concentration at the baseline and those still HBV-DNA-positive after 6 months of treatment. It should be used only for patients with a low baseline viral load.29,30

Currently, ETV and TDF are used singularly in developed countries, but their cost is a serious obstacle to their use in low-income countries.

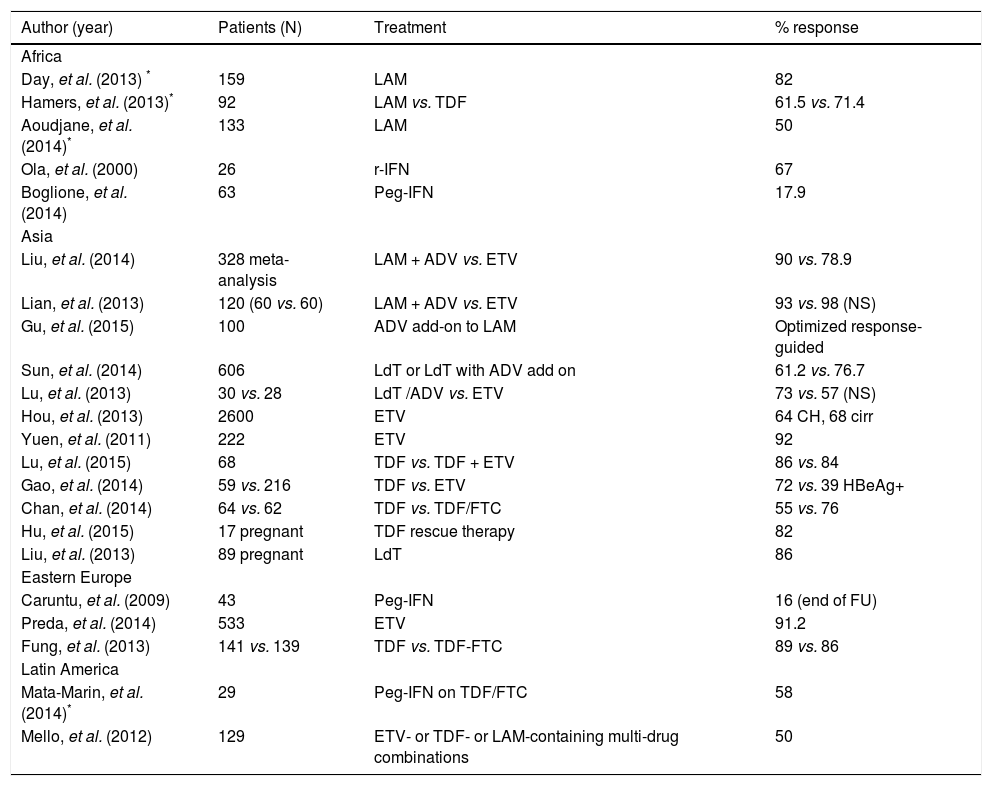

Recent studies on the treatment of chronic HBV infection in low-income countries are shown in table 1.

Recent studies on HBV treatment in developing countries of the four continents studied.

| Author (year) | Patients (N) | Treatment | % response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | |||

| Day, et al. (2013) * | 159 | LAM | 82 |

| Hamers, et al. (2013)* | 92 | LAM vs. TDF | 61.5 vs. 71.4 |

| Aoudjane, et al. (2014)* | 133 | LAM | 50 |

| Ola, et al. (2000) | 26 | r-IFN | 67 |

| Boglione, et al. (2014) | 63 | Peg-IFN | 17.9 |

| Asia | |||

| Liu, et al. (2014) | 328 meta-analysis | LAM + ADV vs. ETV | 90 vs. 78.9 |

| Lian, et al. (2013) | 120 (60 vs. 60) | LAM + ADV vs. ETV | 93 vs. 98 (NS) |

| Gu, et al. (2015) | 100 | ADV add-on to LAM | Optimized response-guided |

| Sun, et al. (2014) | 606 | LdT or LdT with ADV add on | 61.2 vs. 76.7 |

| Lu, et al. (2013) | 30 vs. 28 | LdT /ADV vs. ETV | 73 vs. 57 (NS) |

| Hou, et al. (2013) | 2600 | ETV | 64 CH, 68 cirr |

| Yuen, et al. (2011) | 222 | ETV | 92 |

| Lu, et al. (2015) | 68 | TDF vs. TDF + ETV | 86 vs. 84 |

| Gao, et al. (2014) | 59 vs. 216 | TDF vs. ETV | 72 vs. 39 HBeAg+ |

| Chan, et al. (2014) | 64 vs. 62 | TDF vs. TDF/FTC | 55 vs. 76 |

| Hu, et al. (2015) | 17 pregnant | TDF rescue therapy | 82 |

| Liu, et al. (2013) | 89 pregnant | LdT | 86 |

| Eastern Europe | |||

| Caruntu, et al. (2009) | 43 | Peg-IFN | 16 (end of FU) |

| Preda, et al. (2014) | 533 | ETV | 91.2 |

| Fung, et al. (2013) | 141 vs. 139 | TDF vs. TDF-FTC | 89 vs. 86 |

| Latin America | |||

| Mata-Marin, et al. (2014)* | 29 | Peg-IFN on TDF/FTC | 58 |

| Mello, et al. (2012) | 129 | ETV- or TDF- or LAM-containing multi-drug combinations | 50 |

In Africa, particularly in sub-Saharan countries, the decision to treat a patient with CHB should be based on a comprehensive evaluation of the stage of the liver disease, the HBV load, the HBeAg/antiHBe status, the HBV genotype, the presence or absence of HIV coinfection, and the socio-economic and cultural levels of the country where the patient lives.45

Many African people are co-infected with chronic HBV and HIV. For these patients, the current international guidelines strongly encourage the use of TDF as part of the antiretroviral therapy (ART).46 Indeed, early administration of ART including TDF for HBV-HIV co-infected subjects is recommended as the treatment of choice,47 since it offers improved health benefits and reduces mortality.48 Instead, most sub-Saharan patients have been treated with lamivudine49–53 and have experienced drug resistance, a virological and clinical breakthrough and liver disease progression. At present, replacing LAM with TDF in the ART therapy is limited by the high cost, even though governments or insurance companies54 take on a large part of the costs.

Few data are available on standard or Peg-IFN treatment in African populations. An old study on a small group of Nigerian patients reported a 67% sustained response to recombinant IFN with an HBsAg loss of 22%,55 whereas a recent Italian study on African immigrants infected with HBV-genotype E found a 17.9% response to Peg-IFN with HBsAg loss of 2.5%.56

Urgent coordination of the prophylactic and therapeutic measures against HBV infection in countries of sub-Saharan Africa is warranted to reduce the spread of the infection and the rate of disease progression.

Treatment of CHB in AsiaIt can be difficult to obtain a complete therapeutic suppression of HBV-DNA replication in HBeAg-positive CHB patients with a high viral load, a clinical condition frequent in Asian CHB patients.

Although TDF and ETV are both considered firstline therapies for CHB, in several Asian contexts they are reputed to be too expensive and, consequently, are not widely used, whereas LAM has been used extensively. A virological and biochemical breakthrough during LAM treatment has been observed more frequently in patients with natural YMDD mutations than in those without.57

The efficacy and safety of the de novo combination LAM + ADV have been reviewed by Liu, et al., who found this combination superior to ETV monotherapy in obtaining a biochemical response, seroconversion to anti-HBe in HBeAg-positive cases and protection against resistance development.58 In another study, the combination of LAM + ADV showed similar efficacy compared to ETV in controlling viral replication, in improving liver function tests and in reducing the occurrence of mortality in patients with decompensated cirrhosis.59 In addition, a multicenter study showed that also add-on therapy of ADV to LAM maintains long-term suppression of HBV replication and improves liver function in CHB patients with compensated cirrhosis.60

Chinese clinical researchers carried out a randomized trial on the efficacy of LdT to treat CHB. In the arm including the addition of ADV for patients with a sub-optimal response at week 24, they obtained a good virological response in 76.7% of cases, low resistance emergence (2.7%) and limited side effects.61 LdT has also been added successfully to ADV in the case of ADV resistance in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis, with a significantly higher rate of HBeAg seroconversion than in patients receiving Entecavir.62

Entecavir treatment has been found to be effective and safe both in clinical trials63 and in real-world experience on large cohorts of HBsAg-positive Asian patients.64,65 ETV treatment was followed by a rapid reduction in serum HBV-DNA levels, which became undetectable in 75% of cases by week 48. Response rates were lower in HBeAg-positive than in HBeAg-negative patients. The efficacy of ETV was similar in compensated and decompensated cirrhosis and therapy-naïve and experienced patients,66 with a resistance rate estimated at approximately 1%.63,65 The antiviral efficacy of ETV has been demonstrated to be superior to LAM, ADV or LdT.66

Tenofovir was found to be effective in patients with a partial response to ETV67 and superior to ETV in suppressing high HBV-DNA levels.68,69 The data from a recent study suggest the combination embricitabine + TDF for highly viremic HBeAg-positive patients with normal ALT.70 Cohort studies have demonstrated that ETV reduces in a period of 5 years the occurrence of HCC and death in Asiatic patients with cirrhosis.71,72 A recent real-world study on 5,374 Korean patients showed that ETV-treated patients have a lower risk of death or liver transplantation, but not of HCC development, than those treated with lamivudine.73

Tenofovir has been demonstrated to be safe and effective in reducing HBV-DNA serum concentration to low or undetectable levels in pregnant women, and thereby in reducing the risk of intra-uterine and perinatal transmission of HBV when combined with passive and active immunization of new-born babies.74–77 TDF has also been demonstrated to be safe and effective in pregnant women with LAM- or LdT-resistant HBV chronic infection.78 Despite having a low genetic barrier, LdT has also been found to be safe and effective in pregnant women.79

Information on the effect of NUC therapy on the HB-sAg serum concentration is scanty. However, it has been demonstrated that both a low baseline HBsAg serum concentration and its consistent reduction under LAM therapy predict HBsAg sero-clearance,80 and that TDF treatment of patients experienced for other NUCs induces variable patterns of decline in the HBsAg serum concentration, a slow reduction being associated with low baseline HBsAg serum values.81

Although NUC therapy has been shown to be safe and effective in treating HBsAg-positive chronic hepatitis, interferon therapy still maintains a role in treating CHB patients in Asia, because it is cheaper than NUCs and provides an immune-mediated control of HBV replication with a finite course of treatment.

Treatment of CHB in Eastern EuropeA multicenter European study showed different approaches to CHB treatment in different countries of Eastern Europe, but, in general, high ALT and/or HBV-DNA serum concentrations were the most frequent drivers of treatment initiation, whereas an unsatisfactory viral load under treatment was the most frequent driver of a treatment switch.82 Furthermore, in Poland and Romania, pegylated interferon or LAM or ADV or LdT monotherapy were more frequently used (about 70%) than ETV or TDF (about 20%) compared to Germany, France and Turkey (about 30% and 65%, respectively), probably due to cost and reimbursement issues.83 Other studies performed on this topic in Eastern Europe are small and some present structural problems. In 2013, however, practical guidelines for treating patients with HBsAg-positive chronic hepatitis were published in Poland.84 Some studies in Eastern Europe evaluated the effect of Peg-IFN and some sought parameters predictive of a sustained virological response (SVR). For example, in 43 HBsAg-positive patients treated with Peg-IFN, Caruntu, et al.85 observed a significant reduction in the HBV-DNA and ALT serum values, together with seroconversion to negative by the end of the follow-up period in 11.6% of the HBeAg-positive cases. In a Romanian study 38.6% of patients achieved SVR and a decrease in HBsAg and HBV-DNA serum concentrations were found to be predictive of SVR.86 These data show the results of a less expensive finite treatment, but which are inferior to those obtained by suppressing HBV replication with NUCs.

At present, only a few studies have been performed on the effectiveness of NUC treatment in Eastern Europe. In a large Romanian study, ETV treatment achieved a suppression of HBV replication in more than 90% of cases,87 whereas LAM therapy did not substantially affect survival in a Serbian study.88 In the former study, a low fibrosis score, low viral load, the HBeAg-negative status and being naïve to antiviral treatment were predictive of a virological response; ETV was administered also to LAM-resistant patients, with a 15% rate of non-responders, possibly because of pre-existing cross-resistance to ETV.87 In a multicentre study involving many countries in Eastern Europe, TDF, administered with or without emtricitabine to LAM-resistant patients, was found to be highly effective, and no case of TDF resistance was registered during the 96 weeks of treatment.89

Despite the marked diversities between Western and Eastern European countries in managing several HBV-related problems, a recent investigation on a large number of CHB patients in 5 European countries showed that similar schedules are in use in Germany, France, Poland, Romania and Turkey to monitor treated and untreated patients.90 Also similar are the parameters used to monitor the course of the diseases (ALT and HBV-DNA serum concentrations) both in treated and untreated patients.

Treatment of CHB in Latin AmericaMost studies carried out in countries in South America enrolled HBV/HIV co-infected patients and confirmed the favorable effects of TDF, LAM and FTC in inhibiting both HIV and HBV replication. Treatment with PEG-IFN was shown to be well tolerated and effective (HBV-DNA suppression obtained in 51.7% of the cases) in HBV/HIV co-infected patients also receiving a TDF/FTC-containing treatment against HIV.91 These patients were infected with HBV genotypes H or G and were HBeAg-positive.91 In HIV/HBV co-infected patients with chronic hepatitis receiving LAM as part of antiretroviral treatment, a significant reduction in the HBV-DNA serum concentration was observed once ETV was added to the treatment schedule.92

A study performed in Mexico showed that nearly 5% of the HBV strains examined presented pre-treatment LAM genotypic resistance.93 A Brazilian study94 showed that more than 50% of the 129 patients were HBV-DNA-positive under ETV or TDF monotherapy or LAM containing a multi-drug combination, due to a LAM-resistance mutation in 47% of them.

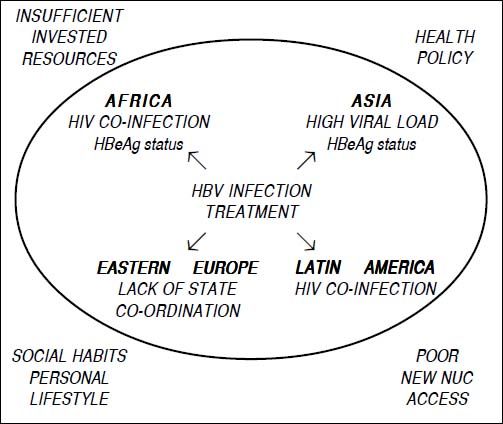

Final CommentsThere are several political, cultural and socio-economic obstacles hampering a correct approach for monitoring and treating patients with CHB in low-income countries, namely HIV co-infection, high HBV load, low economic resources, patients’ poor adherence or insufficiency of the healthcare system of some countries (Figure 1). These factors may favor the deterioration of CHB and the progression to cirrhosis or HCC. Correct management of chronic HBV infection and the application of appropriate treatment schedules in low-income countries could be achieved by investing more resources to apply the procedures suggested in the current international guidelines. The healthcare system of each country should organize or further promote screening programs for subjects who are at risk of acquiring HBV infection, as well as nationwide educational campaigns, universal vaccination campaigns against HBV infection and access of HBV patients to a clinical evaluation and possible treatment.

Abbreviations- •

ADV: adefovir.

- •

anti-HBe: hepatits B virus e antibodies.

- •

anti-HBs: hepatits B virus surface antibodies.

- •

ART: antiretroviral therapy.

- •

CHB: chronic hepatitis B.

- •

ETV: entecavir.

- •

HBeAg: hepatits B virus e antigen.

- •

HBsAg: hepatits B virus surface antigen.

- •

HBV: hepatitis B virus.

- •

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

- •

LAM: lamivudine.

- •

LdT: telbivudine.

- •

NUCs: nucleoside analogues.

- •

Peg-IFN: pegylated interferon.

- •

TDF: tenofovir.