Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a global healthcare burden. According to the latest GLOBOCAN, in 2022, liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer deaths globally, of which HCC accounts for 80 % of liver cancer [1]. The main etiological risk factors for HCC include chronic infection such as hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [2,3]. Although the implementation of HBV universal vaccination [4], and the widespread use of highly effective antiviral therapies for HBV and HCV have reduced the incidence of cirrhosis and hence viral related-HCC [5,6], the rise of patients with MASLD, and the increasingly aging population in many parts of the world are expected to increase the disease burden of HCC. In certain places, MASLD may even become the leading etiology of HCC [7].

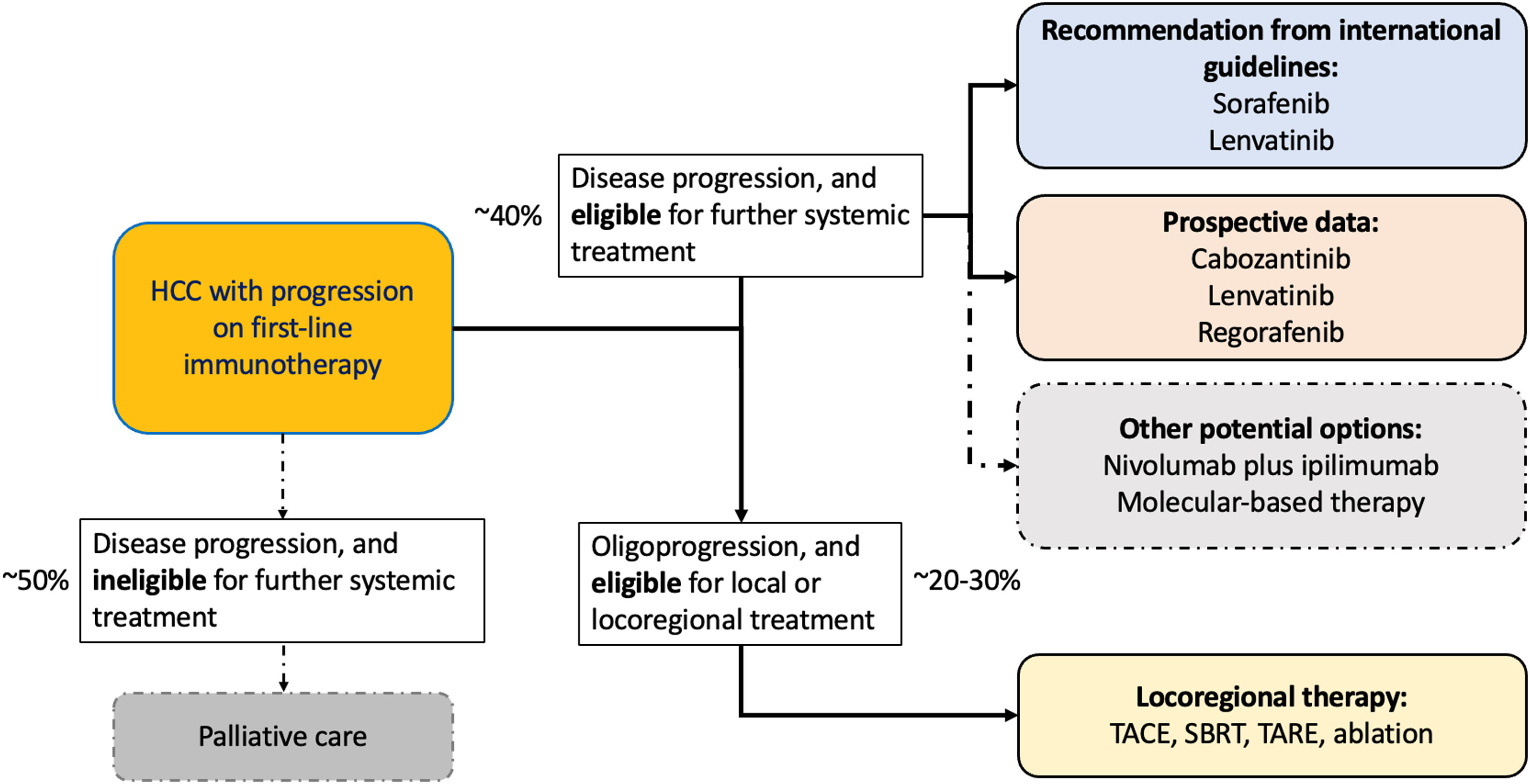

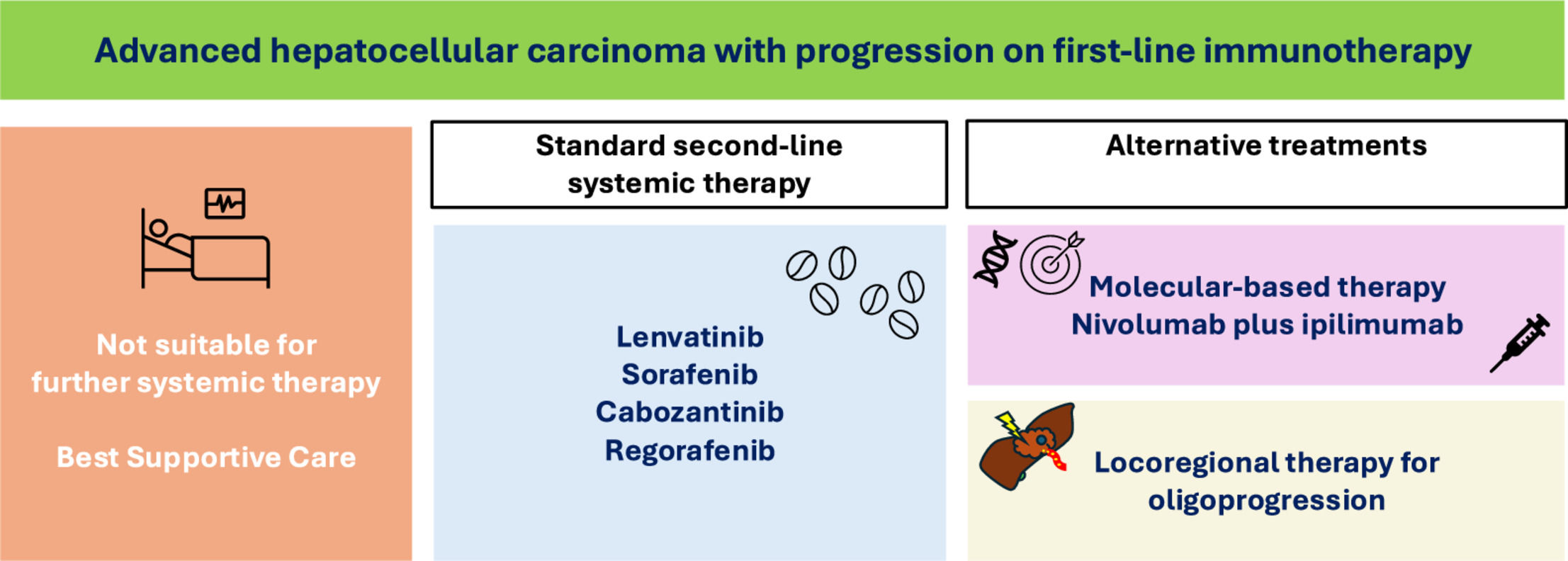

The introduction of immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), has revolutionized the treatment landscape of HCC. These therapies have significantly improved overall survival, increasing from a mere 6 to 10 months during the era of sorafenib [8,9], the first systemic treatment approved for HCC in 2008, to almost 2 years currently based on the latest phase III trials in 2024 [10,11]. Unfortunately, only about 30 % of patients respond to ICI, and long-term survivors were only seen in 20 to 30 % of patients [10–13]. Most patients would develop disease progression within 6 months. Upon disease progression, about 40 to 50 % of these patients will be eligible for subsequent treatments [10,11,14–17]. Currently, international guidelines recommend that patients who progress on first-line immunotherapy be treated with multi-kinase inhibitors (MKIs). These agents have been approved in the first-line setting due to their established efficacy and safety, the rationale of offering an alternative mechanism of action, and their accessibility, despite the lack of high-quality data to guide management in this context [18–20].

Recently, three phase II prospective trials have reported promising safety and efficacy signal of MKI-based regimens in the post-immunotherapy setting [21–23]. These trials represent the first prospective evidence to demonstrate second-line MKIs following immunotherapy are effective and safe. Furthermore, emerging retrospective studies suggest that addition of an anti-CTLA-4, or local therapy in oligoprogression, may bring benefits in some patients who progressed on first-line immunotherapy [24,25]. Molecular-driven treatment is another feasible treatment strategy in a minority of patients who harbour actionable mutations [26]. In this Review, we provide an overview of the latest evidence in the setting of post immunotherapy treatment for HCC and propose a pragmatic approach on treatment strategies following progression on first-line immunotherapy.

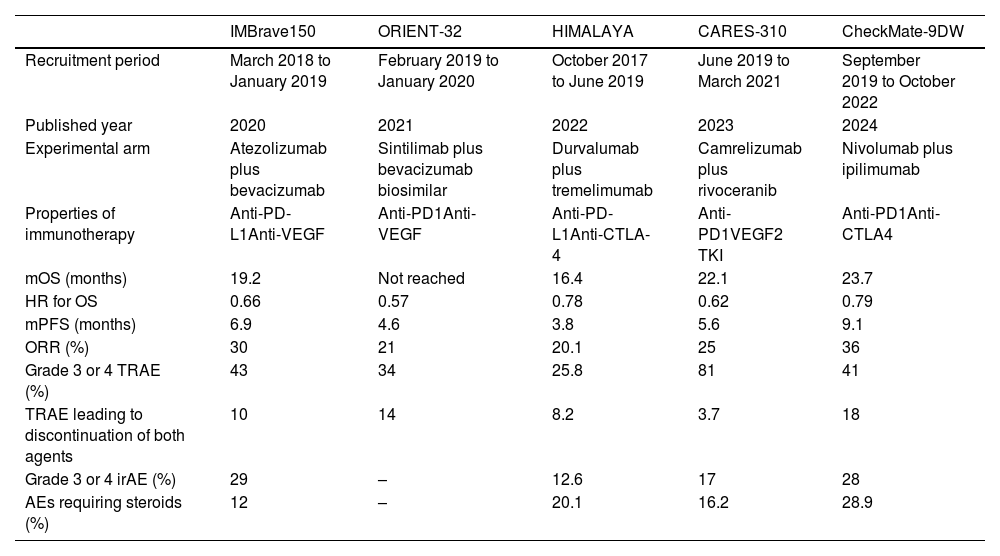

2Current first-line immunotherapy landscapeImmunotherapy has transformed the treatment landscape for unresectable HCC. HCC is typically a hypervascular tumour with a relatively ‘hot’ tumor microenvironment. It represents an excellent model to illustrate the importance of targeting different steps in the cancer-immunity cycle in order to restore effective immunosurveillance [27,28]. MKIs such as lenvatinib or sorafenib had remained as the first-line standard of care for unresectable for HCC for more than a decade, with a median overall survival (OS) of around 1 year and unsatisfactory response rates [8,29]. However, these MKIs have been superseded by immunotherapy combination, with multiple international phase III trials showing immunotherapy combinations prolong OS to about 2 years, with an expected response rate of 20 % to 30 %, which is unprecedent in the history of HCC [11,13,16,30,31]. Furthermore, approximately 20 % of patients who received dual immunotherapy would be alive beyond 3 to 4 years after initiation of systemic treatment, signifying long-term survival is now possible even in advanced disease [11,14]. Of note, majority of patients would still progress between 3 and 9 months while on first-line immunotherapy combination, which imply that the prolonged OS seen in recent trials must have been driven by the availability of subsequent treatments (Table 1). In this section, we will first review the findings of the latest positive phase III trials in first-line immunotherapy combination for advanced HCC (Table 1).

Positive phase 3 clinical trials evaluating efficacy and safety of immunotherapy combination in advanced HCC.

| IMBrave150 | ORIENT-32 | HIMALAYA | CARES-310 | CheckMate-9DW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment period | March 2018 to January 2019 | February 2019 to January 2020 | October 2017 to June 2019 | June 2019 to March 2021 | September 2019 to October 2022 |

| Published year | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| Experimental arm | Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab | Sintilimab plus bevacizumab biosimilar | Durvalumab plus tremelimumab | Camrelizumab plus rivoceranib | Nivolumab plus ipilimumab |

| Properties of immunotherapy | Anti-PD-L1Anti-VEGF | Anti-PD1Anti-VEGF | Anti-PD-L1Anti-CTLA-4 | Anti-PD1VEGF2 TKI | Anti-PD1Anti-CTLA4 |

| mOS (months) | 19.2 | Not reached | 16.4 | 22.1 | 23.7 |

| HR for OS | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.79 |

| mPFS (months) | 6.9 | 4.6 | 3.8 | 5.6 | 9.1 |

| ORR (%) | 30 | 21 | 20.1 | 25 | 36 |

| Grade 3 or 4 TRAE (%) | 43 | 34 | 25.8 | 81 | 41 |

| TRAE leading to discontinuation of both agents | 10 | 14 | 8.2 | 3.7 | 18 |

| Grade 3 or 4 irAE (%) | 29 | – | 12.6 | 17 | 28 |

| AEs requiring steroids (%) | 12 | – | 20.1 | 16.2 | 28.9 |

HR: hazard ratio; irAE: immune-related adverse events; mOS: median overall survival; mPFS: median progression free survival; TRAE: treatment-related adverse events; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

The first phase III trial that demonstrated superiority of immunotherapy combination over MKI was the IMbrave150 study. IMbrave150 study was a global, open-label, phase 3 trial that randomized 501 patients with unresectable HCC in a 2:1 ratio into the treatment arm atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1) plus bevacizumab (anti-VEGF) or the control arm sorafenib (Table 2) [32]. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab resulted in improved median OS at 19.2 months compared to sorafenib at 13.4 months [12]. The overall response rate (ORR) was also improved with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab to 30 %, compared to 11 % for sorafenib. High-grade treatment related adverse events (TRAEs) was seen 43 % of patients treated with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab, compared to 46 % in the sorafenib arm. However, adverse events (AEs) leading to withdrawal from atezolizumab plus bevacizumab was uncommon at 10 % and the requirement of steroids for immune-mediated events were only seen in 12 % of patients [12,33].

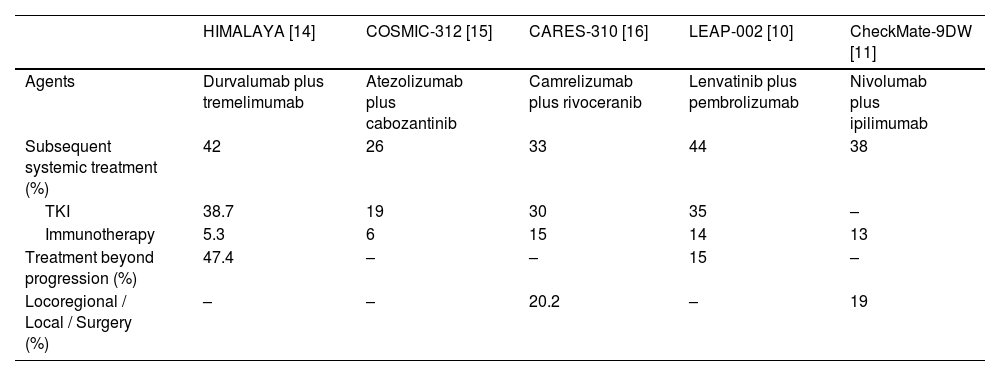

Subsequent therapies in the pivotal phase 3 immunotherapy combination trials in advanced HCC.

| HIMALAYA [14] | COSMIC-312 [15] | CARES-310 [16] | LEAP-002 [10] | CheckMate-9DW [11] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agents | Durvalumab plus tremelimumab | Atezolizumab plus cabozantinib | Camrelizumab plus rivoceranib | Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab | Nivolumab plus ipilimumab |

| Subsequent systemic treatment (%) | 42 | 26 | 33 | 44 | 38 |

| TKI | 38.7 | 19 | 30 | 35 | – |

| Immunotherapy | 5.3 | 6 | 15 | 14 | 13 |

| Treatment beyond progression (%) | 47.4 | – | – | 15 | – |

| Locoregional / Local / Surgery (%) | – | – | 20.2 | – | 19 |

Following IMbrave150, a number of phase III trials evaluating immunotherapy combination have also demonstrated superior outcomes compared to sorafenib, further establishing the role of first-line immunotherapy combination. The HIMALAYA trial was a global, multicentre, phase 3 randomized trial compared the efficacy and safety of durvalumab (anti-PD-L1) and tremelimumab (anti-CTLA-4) with sorafenib [13], which was the first phase 3 trial to evaluate the use of anti-CTLA-4 in advanced HCC (Table 1). 1171 patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio, treated with one dose of tremelimumab 300 mg plus durvalumab 1500 mg every 4 weeks (STRIDE regimen), durvalumab 1500 mg every 4 weeks, and sorafenib 400 mg twice daily. The primary endpoint was median OS comparing STRIDE versus sorafenib. Secondary endpoint included noninferiority for OS between durvalumab and sorafenib. The STRIDE regimen demonstrated superior median OS at 16.4 months compared to sorafenib at 13.8 months. Noninferiority of durvalumab was also achieved at 16.6 months. ORR was superior with the STRIDE regimen at 20.1 % compared to sorafenib at 5.1 %. ORR in the durvalumab arm was 17.0 %. Grade 3 or 4 TRAEs occurred in 25.8 %, 12.9 % and 36.9 % in the STRIDE regimen, durvalumab arm and sorafenib arm respectively. In particular, grade 3 or 4 treatment-related immune-related AEs (irAEs) were only seen in 12.6 % of patients treated with the STRIDE regimen and only about 20 % of patients required use of steroids (Table 1) [13]. In the recent 4-year update, it has been shown that approximately 25 % of patients who were treated with the STRIDE regimen were still alive, showing that long-term survivors are possible in advanced HCC for the first time [14].

Three other phase 3 trials also reported positive results including two China study ORIENT-32 (sintilimab [anti-PD-1] plus bevacizumab biosimilar versus sorafenib) [31], CARES-310 (camrelizumab [anti-PD-1] plus rivoceranib [anti-VEGFR2] versus sorafenib) [16], and CheckMate-9DW (nivolumab [anti-PD-1] plus ipilimumab [anti-CTLA-4] versus sorafenib or lenvatinib) (Table 1) [11]. Of note, CheckMate-9DW using nivolumab 1 mg/kg plus ipilimumab 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for up to four cycles, followed by maintenance nivolumab 480 mg every 4 weeks, reported the highest ORR (36 %) and median OS (23.7 months) seen compared to previous published phase III trials (Table 1). But this apparently comes with a cost of higher toxicity with grade 3 or 4 TRAEs and immune-related AEs occurred in 41 % and 28 % of patients treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab respectively, and 29 % of patients required high-dose steroids as a result [11].

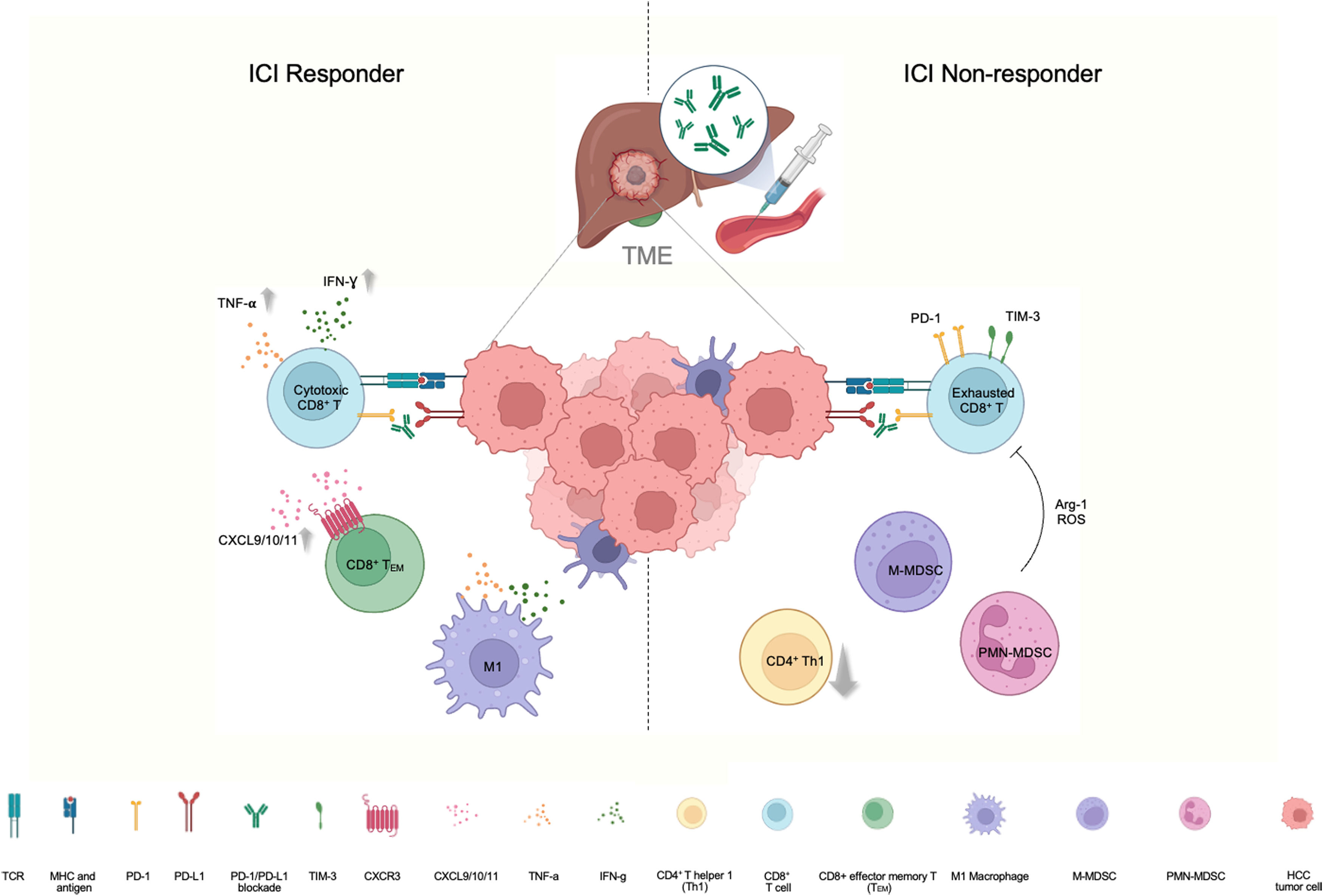

3Immunomodulation of tumour microenvironment and its impact on subsequent treatmentCurrently, systemic treatment for HCC is guided by clinical features rather biological markers, as none have been identified so far. Significant effort is still required to deliver precision care for HCC, akin to that for lung cancer or breast cancer [34,35]. Research into the tumour microenvironment (TME) may offer insights for identifying responders, and uncover new opportunities for the many patients who do not respond to initial immunotherapy (Fig. 1). In a clinical study which examined matched blood and tumour specimens from HCC patients treated with anti-PD-1 therapy, it was found that peripheral enrichment of CXCR3+CD8+ effector memory T (TEM) cells and antigen-presenting cells (APC) were associated with response and survival. Comparison of pre- and on-treatment tumour specimens showed upregulation of genes related to T-cell activation and antigen presentation, echoing the peripheral enrichments of TEM cells and APC. Furthermore, bulk-RNA sequencing of tumor tissues exhibited enrichment of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 in responders. These chemokines are known to bind to CXCR3, further supporting tumour recruitment of CXCR3+CD8+ effector memory TEM cells [36]. For anti-PD-L1-resistant-HCC tumours, preclinical models suggested that the TME became T cell-excluded and immunosuppressive under ICI therapeutic pressure. Specifically, the resistant model displayed reduced CD4+ T helper 1 (Th1) cells and CD8+ T cells but increased monocytic (M)- and polymorphonuclear (PMN)-myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in both Hepa1–6 and RIL-175 HCC tumors upon ICI treatment. Apart from changes in immune cell proportions, the T cell phenotype also transitioned from cytotoxic to exhausted CD8+ T cells in the PD-L1-resistant tumours, exhibiting elevated levels of immune-checkpoint molecules such as PD-1 and T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3), along with reduced levels of cytotoxic cytokines such as interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [37]. Collectively, the recruitment of immuno-active and immuno-suppressive cells and chemokines within the TME and in peripheral blood, may provide insights into response and survival for patients undergoing immunotherapy. This also highlights the need to target alternative immune checkpoints or pathways to enhance therapeutic efficacy of immunotherapy.

Cellular signaling and interaction in the tumor microenvironment (TME) in response to immune-checkpoint targeting.

Left: In ICI responders, there is an increase in IFN-g and TNF-a in cytotoxic T cells, along with an increase in CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, which are key chemokines binding to CXCR3, supporting the recruitment of CXCR3+CD8+ effector memory T (TEM) cells in responders. There is enrichment of M1 macrophages that possess anti-tumor properties with IFN-g and TNF-a secretion. Right: In ICI non-responders, there is an increase in the abundance of immunosuppressive cells, including M-MDSC and PMN-MDSC, which mediate immunosuppressive effects through Arg-1 and ROS, coupled with an increase in checkpoint expression of TIM-3 and PD-1 in CD8+ T cells in an exhausted state, and a decrease in CD4+ T helper 1 cells, leading to HCC tumor escape. (Created with BioRender.com).

Based on experiences from the published phase 3 trials and global retrospective studies, 40 to 50 % of patients who progressed on first-line immunotherapy are treated with subsequent systemic treatments (Table 2) [10,11,14–17,38]. International guidelines support this approach even though there are no high-quality evidence in this context [18–20]. Based on findings of these retrospective studies, the efficacy and safety of second-line sorafenib and lenvatinib after progression on immunotherapy appeared to be comparable to their use in the first-line setting [8,17,29,39].

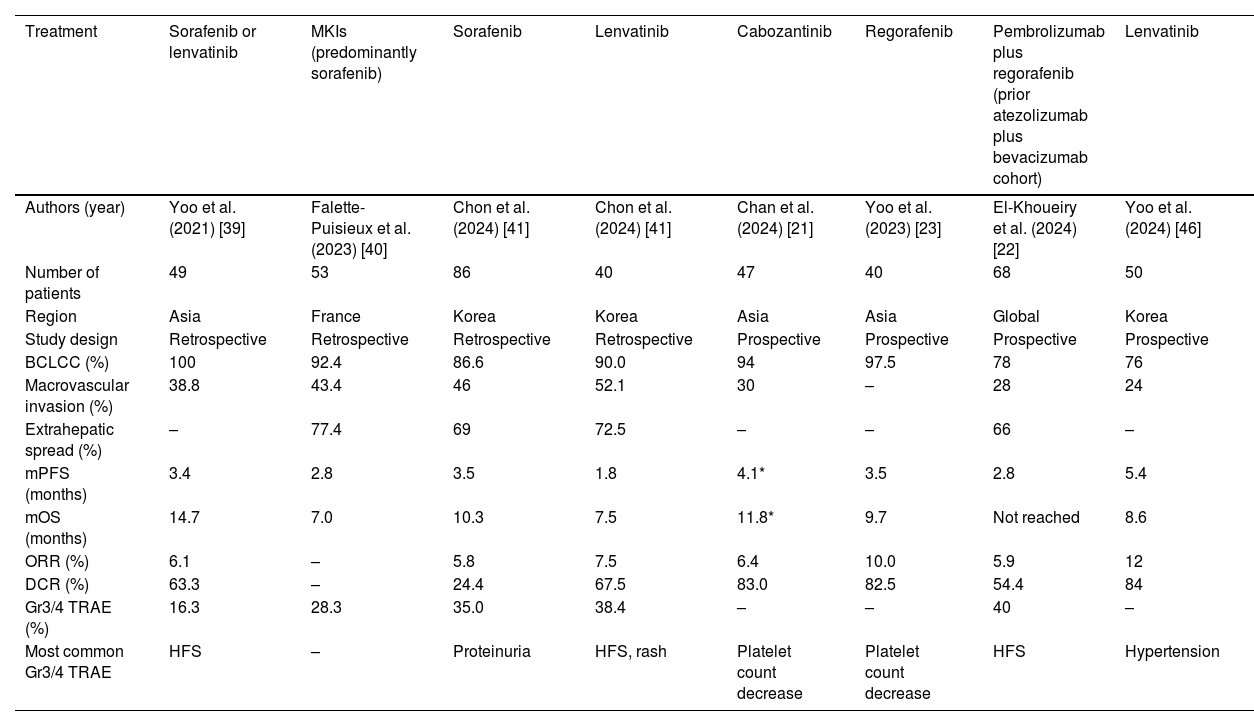

The first report investigating MKIs after progression of immunotherapy in unresectable HCC came from Asia [39]. In this retrospective study, 49 out of 71 patients treated with first-line atezolizumab plus bevacizumab were enrolled. 29 patients were treated with sorafenib, 19 patients were treated with lenvatinib, and 1 patient was treated with cabozantinib. The median PFS was 3.4 months, and median OS was 14.7 months (Table 3). Consistent with the REFLECT trial [29], the median PFS was better in the lenvatinib group compared to the sorafenib group (6.1 months versus 2.5 months; p = 0.004), but the median OS was similar (11.2 months versus 16.6 months; p = 0.35). Overall ORR was 6.1 % and DCR was 63.3 %, but patients treated with sorafenib achieved stable disease (SD) at best. Grade 3 or higher TRAEs occurred in 8 (16.3 %) patients, and the most common grade 3 or higher toxicity was hand-foot syndrome (8.2 %) [39]. Subsequently, a few retrospective studies from Asia and Europe also reported similar outcomes of second-line sorafenib or lenvatinib after progression of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab, with an ORR of around 5 % to 10 %, median PFS of 2 to 3 months, and a median OS of 7 to 10 months [40,41]. Similar results were also observed in retrospective studies evaluating cabozantinib following progression on immunotherapy, although these studies included a heterogeneous group of patients with multiple prior lines of treatments. Nonetheless, cabozantinib resulted in an ORR of 5 %, median PFS of 3 months, and median OS between 7 and 8 months [42,43].

Selected clinical studies reporting efficacy and safety of subsequent MKI treatments following progression of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab.

| Treatment | Sorafenib or lenvatinib | MKIs (predominantly sorafenib) | Sorafenib | Lenvatinib | Cabozantinib | Regorafenib | Pembrolizumab plus regorafenib (prior atezolizumab plus bevacizumab cohort) | Lenvatinib |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors (year) | Yoo et al. (2021) [39] | Falette-Puisieux et al. (2023) [40] | Chon et al. (2024) [41] | Chon et al. (2024) [41] | Chan et al. (2024) [21] | Yoo et al. (2023) [23] | El-Khoueiry et al. (2024) [22] | Yoo et al. (2024) [46] |

| Number of patients | 49 | 53 | 86 | 40 | 47 | 40 | 68 | 50 |

| Region | Asia | France | Korea | Korea | Asia | Asia | Global | Korea |

| Study design | Retrospective | Retrospective | Retrospective | Retrospective | Prospective | Prospective | Prospective | Prospective |

| BCLCC (%) | 100 | 92.4 | 86.6 | 90.0 | 94 | 97.5 | 78 | 76 |

| Macrovascular invasion (%) | 38.8 | 43.4 | 46 | 52.1 | 30 | – | 28 | 24 |

| Extrahepatic spread (%) | – | 77.4 | 69 | 72.5 | – | – | 66 | – |

| mPFS (months) | 3.4 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 1.8 | 4.1* | 3.5 | 2.8 | 5.4 |

| mOS (months) | 14.7 | 7.0 | 10.3 | 7.5 | 11.8* | 9.7 | Not reached | 8.6 |

| ORR (%) | 6.1 | – | 5.8 | 7.5 | 6.4 | 10.0 | 5.9 | 12 |

| DCR (%) | 63.3 | – | 24.4 | 67.5 | 83.0 | 82.5 | 54.4 | 84 |

| Gr3/4 TRAE (%) | 16.3 | 28.3 | 35.0 | 38.4 | – | – | 40 | – |

| Most common Gr3/4 TRAE | HFS | – | Proteinuria | HFS, rash | Platelet count decrease | Platelet count decrease | HFS | Hypertension |

BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; DCR: disease control rates; HFS: hand-foot syndrome; mOS: median overall survival; mPFS: median progression-free survival; ORR: objective response rates.

Recently, a global collaborative study provided real world evidence on the treatment outcomes of MKIs following progression on first-line immunotherapy. In a prospectively collected, international cohort of patients (n = 464) from 46 centres in 5 countries (Italy, Germany, Portugal, Japan, the Republic of Korea) with advanced or intermediate HCC treated with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab between 2018 and 2022, 233 out of 464 (50.2 %) patients who received second-line systemic treatment following progression on atezolizumab plus bevacizumab. Majority received MKIs including sorafenib (n = 43, 18.4 %), lenvatinib (n = 84, 36 %) or cabozantinib (n = 23, 9.9 %) [17]. Only 6 patients received immunotherapy afterwards. The overall median OS in those who received subsequent MKIs was 15.7 months. Individually, the median OS for patients treated with subsequent sorafenib, lenvatinib, or cabozantinib were 14.2 months, 17.0 months and 12.3 months respectively [17]. In another prospectively collected, international cohort from 13 tertiary-care referral centers located in Europe, the United States and Asia, 364 patients with unresectable HCCs undergoing immunotherapy treatment between 2017 and 2021 were recruited. Most patients (n = 292, 80.2 %) received anti-PD-(L)1 monotherapy first-line. Only 23 (6.3 %) patients received first-line anti-PD-(L)1 plus anti-CTLA-4 combination, and 17 (4.7 %) patients received prior atezolizumab plus bevacizumab. It was found that 55 % of patients received subsequent anticancer therapy after disease progression [38]. 64 (17.6 %) patients continued immunotherapy beyond progression. Another 108 (29.7 %) patients switched to MKIs [38]. In patients who received immunotherapy beyond progression, their median OS was 5.6 months. In patients who received MKIs after progression on immunotherapy, their median OS was 10.4 months.

For patients who progressed on the combination of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-(L)1 therapy, a similar proportion continued to receive second-line therapies compared to those who progressed on atezolizumab plus bevacizumab. In the HIMALAYA trial, 166 out of 393 patients (42.2 %) received subsequent anticancer treatment after discontinuing the STRIDE regimen [14]. Among these, 152 out of 166 patients (91.6 %) received targeted therapy, while 21 out of 166 patients (12.7 %) continued with another form of immunotherapy. In the recently reported CheckMate-9DW trial, 128 out of 335 patients (38.2 %) who progressed on nivolumab plus ipilimumab received subsequent therapies (see Table 2). The most common subsequent systemic therapy was anti-VEGF agents (73.4 %), and immunotherapy was continued in 44 patients (34.3 %).

4.2Prospective evidence on second-line MKIsAlthough sorafenib and lenvatinib are commonly selected as the choice of MKIs following progression on first-line immunotherapy, there is no high-quality evidence to support this approach. Retrospective studies provided insights in their efficacy and safety, but these studies were prone to various bias (e.g. selection bias, recall bias) and often included a heterogeneous population, making it difficult to interpret their outcomes [44].

Four phase II prospective trials investigated the efficacy and safety of MKIs in the post-immunotherapy setting (Table 3) [21–23]. The first prospective trial published was a multicentre phase II study conducted in Asia on cabozantinib in patients with advanced HCC who progressed on immunotherapy [21]. The study included 47 patients who had received one or more prior lines of immunotherapy. Most of them (94 %) had BCLCC disease and 30 % of them had portal vein thrombosis. All patients received cabozantinib 60 mg daily, but the median dose received was 40 mg daily. The overall median PFS was 4.1 months, and the median OS was 9.9 months. When restricting the use of cabozantinib in the second-line setting, cabozantinib was associated with a median PFS of 4.3 months and median OS of 14.3 months. When focusing on the patients who progressed on atezolizumab plus bevacizumab, the median PFS was 4.3 months and median OS was 11.8 months respectively (Table 3). The safety profile of cabozantinib was consistent with previously reported [45], with the most frequent AEs including hand-foot skin reaction (42.6 %), fatigue (38.3 %), diarrhea (21.2 %), hypertension (21.2 %) and proteinuria (21.2 %). Nonetheless, grade 3 or higher AEs was uncommon and the most common grade 3 or higher toxicity was thrombocytopenia (6.4 %) (Table 3) [21].

The REGONEXT trial is a Korean study that evaluated the use of regorafenib in 40 patients who progressed on initial atezolizumab plus bevacizumab [23]. All but one patients (97.5 %) had BCLCC disease. The overall median PFS was 3.5 months, and the median OS was 9.7 months. The median OS since the start of prior atezolizumab plus bevacizumab was 16.6 months. ORR and DCR were 10.0 % and 82.5 % respectively. The most common grade 3 or higher TRAEs were thrombocytopenia (5.0 %), palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (2.5 %) and fatigue (2.5 %) (Table 3) [23].

In the 2024 ASCO meeting, another phase II study reported the outcomes of patients who were treated with regorafenib plus pembrolizumab following progression on first-line immunotherapy [22]. In this study, 95 patients were enrolled internationally, with patients who had received prior atezolizumab plus bevacizumab comprising cohort 1 (n = 68) and those who had received a different prior immunotherapy in cohort 2 (n = 27). About 80 % had BCLCC disease, and 28 % had macrovascular invasion. Among the 68 patients who progressed on atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and received regorafenib plus pembrolizumab, the median PFS was 2.8 months, and ORR was 5.9 %. For the remaining 27 patients who received a different immunotherapy in the first-line setting, the median PFS was 4.2 months, and ORR was 11.1 %. Due to the relatively short follow-up time (median 7.1 months), the median OS for both cohorts are not mature yet. TRAEs were generally consistent with previous studies on regorafenib and pembrolizumab, but one patient developed cardiac arrest resulted in mortality (Table 3).

In the ESMO Asia 2024 meeting, a phase II study showed that lenvatinib provided similar efficacy with other MKIs in the post atezolizumab plus bevacizumab setting [46]. In this Korean multicentre study, 50 patients who progressed on atezolizumab plus bevacizumab were prospectively recruited to receive lenvatinib. The median PFS was 5.4 months, and the median OS was reported to be 8.6 months but the data was immature. ORR was observed in 6 (12 %) patients and DCR was 84 %. Grade ≥3 TRAEs were consistent with previous experience of lenvatinib, with the most common grade ≥3 toxicity being hypertension, anorexia and proteinuria.

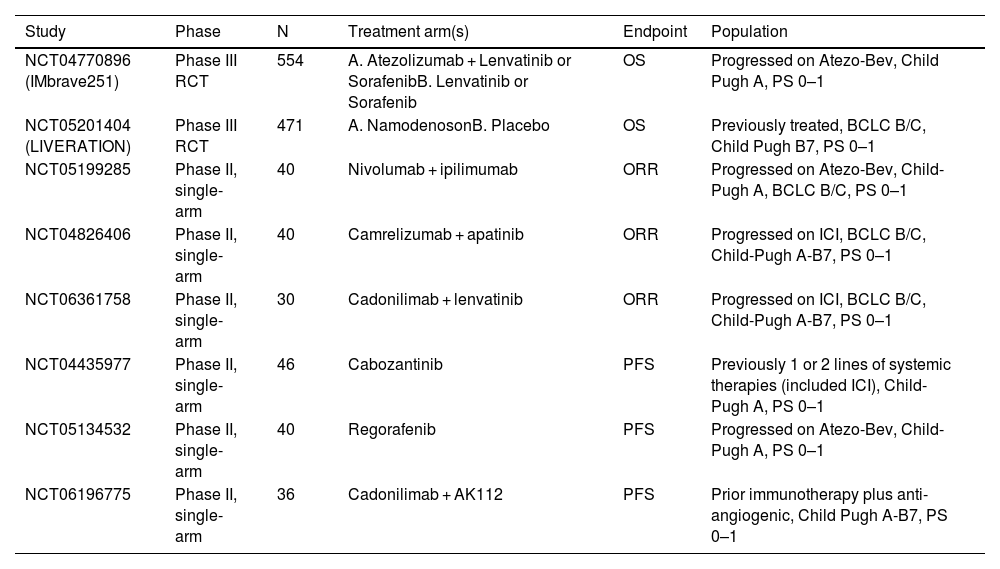

The two phase II studies that examined regorafenib generated some interesting observations for patients who progressed on atezolizumab plus bevacizumab. Although patients enrolled in REGONEXT appeared to have more advanced disease (e.g. higher proportion of BCLCC), the median PFS and ORR reported were similar. It would seem to suggest that the continuation of immunotherapy with pembrolizumab, which targets the same immune checkpoint as atezolizumab, in patients who progressed on atezolizumab plus bevacizumab did not provide substantial clinical benefits to regorafenib alone. A phase 3 trial (IMBrave251) is ongoing, and hopefully will provide the answer to the question on whether continuation of immunotherapy following progression is needed. The study randomized patients who progressed on atezolizumab plus bevacizumab into atezolizumab plus lenvatinib or sorafenib versus lenvatinib or sorafenib alone (Table 4). The study has already completed accrual and is expected to report its findings in 2025.

Ongoing studies on systemic treatment following progression on immunotherapy.

| Study | Phase | N | Treatment arm(s) | Endpoint | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04770896 (IMbrave251) | Phase III RCT | 554 | A. Atezolizumab + Lenvatinib or SorafenibB. Lenvatinib or Sorafenib | OS | Progressed on Atezo-Bev, Child Pugh A, PS 0–1 |

| NCT05201404 (LIVERATION) | Phase III RCT | 471 | A. NamodenosonB. Placebo | OS | Previously treated, BCLC B/C, Child Pugh B7, PS 0–1 |

| NCT05199285 | Phase II, single-arm | 40 | Nivolumab + ipilimumab | ORR | Progressed on Atezo-Bev, Child-Pugh A, BCLC B/C, PS 0–1 |

| NCT04826406 | Phase II, single-arm | 40 | Camrelizumab + apatinib | ORR | Progressed on ICI, BCLC B/C, Child-Pugh A-B7, PS 0–1 |

| NCT06361758 | Phase II, single-arm | 30 | Cadonilimab + lenvatinib | ORR | Progressed on ICI, BCLC B/C, Child-Pugh A-B7, PS 0–1 |

| NCT04435977 | Phase II, single-arm | 46 | Cabozantinib | PFS | Previously 1 or 2 lines of systemic therapies (included ICI), Child-Pugh A, PS 0–1 |

| NCT05134532 | Phase II, single-arm | 40 | Regorafenib | PFS | Progressed on Atezo-Bev, Child-Pugh A, PS 0–1 |

| NCT06196775 | Phase II, single-arm | 36 | Cadonilimab + AK112 | PFS | Prior immunotherapy plus anti-angiogenic, Child Pugh A-B7, PS 0–1 |

BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; ICI: immune checkpoint inhibitor; PS: ORR: objective response rates; OS: overall survival; PFS: progression-free survival; WHO performance status; RCT: randomized controlled trial.

TP53, TERT, and CTNNB1 are common mutations identified in HCC but they are undruggable [47]. As a result, progress in molecular directed therapy for HCC has been slow, compared to other cancer types such as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) or breast cancer. However, small percentage of patients may harbour actionable mutations that might benefit from targeted therapies. A proof-of-concept study under the “French Medicine Genomic program 2025” examined the molecular adapted approach in patients with advanced HCC who were refractory to standard systemic treatment atezolizumab plus bevacizumab [26]. In this study, 16 HCC patients and 4 hepato-cholangiocarcinoma (HCCK) patients who progressed on atezolizumab plus bevacizumab were recruited. These patients underwent genomic analysis including whole-genome/-exome sequencing on tumour and blood samples, as well as RNA sequencing on the tumour if feasible. Among them, druggable mutations were identified in 14 patients, and 9 of them (7 HCC and 2 HCCK) subsequently received a matched targeted therapy. Among the 9 patients who received the matched systemic therapy, 3 had CCND1/FGF19 amplification and they received a MEK inhibitor trametinib, 3 patients were treated with everolimus for TSC1, TSC2 and PTEN inactivating mutation, 1 patient received olaparib for homologous recombination deficiency (HRD), 1 patient received olaparib plus trastuzumab due to combined homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) and overexpression of ERBB2, and 1 patient received palbociclib due to CDK4 amplification. Survival at 1 year for these patients was 60 %, with 3 patients achieved either stable disease or an objective radiological response. In particular, the patient with TSC2 Leu423fs mutation treated with everolimus achieved complete remission at 6 months [26]. Everolimus is a mTOR inhibitor which can target hyperactive signaling along the PI3 K pathway such as TSC1 and TSC2 [48]. Of note, everolimus was evaluated in the EVOLVE-1 trial in patients with advanced HCC who failed sorafenib. In this molecular unselected population, the trial failed to demonstrate overall survival benefits with everolimus over placebo, despite a higher DCR was observed (56.1 % vs. 45.1 %, p = 0.01) [49]. In a subsequent translational study of the EVOLVE-1 trial, it was observed that 6 out of 10 patients with TSC2 expression loss and were treated with everolimus, had a substantially longer survival than that reported in the trial for the overall population (9.53 to 32.72 months versus 7.56 months) [48]. Given these findings, a molecular directed approach might be an option when existing therapies have been exhausted, in particular in patients with TSC1/2 inactivating mutation, which is observed at a rate of 5 to 10 % overall and may be enriched in HBV-HCC [48,50].

5Addition of anti-CTLA-4 as a salvage therapy for immunotherapy progressionAfter progression on a previous immunotherapy agent, it remains uncertain whether continuation of further immunotherapy, which can be in the form of either addition of CTLA-4 blockade with an PD-(L)1 agent, or continuation of PD-(L)1 agent (either the same or a different one) with or without a MKI partner. This can be a particularly attractive strategy in patients who developed severe side effects from anti-VEGF, such as bleeding events, which render them no longer suitable for majority of the MKIs. Preclinical studies have shown that addition of an anti-CTLA-4 agent to PD-(L)1 therapy led to enhance anti-tumour efficacy such as greater expansion of activated CD8+ T-cells, expansion of Th1-like CD4 effector T-cells, and decreases in Tregs [51]. Efficacy of addition of an anti-CTLA-4 agent as a way to reverse resistance to anti-PD-(L)1 has also been reported in multiple prospective trials in advanced melanoma [52–54].

The addition of anti-CTLA-4 as a salvage strategy for patients progressed on anti-PD-(L)1 or other immunotherapy combination has been tested in advanced HCC. In a small cohort of 10 patients who received combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab after progression on atezolizumab plus bevacizumab or nivolumab plus lenvatinib, 3 patients (30 %) experienced confirmed objective responses [55]. In another small cohort of 32 patients who progressed on anti-PD-(L)1-based therapy subsequently treated with combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab, the ORR was 22 % (7/32) [56]. Half of these patients had received prior atezolizumab plus bevacizumab. The median PFS was 2.9 months and the median OS was 9.2 months. However, irAEs were observed in 13 (41 %) patients, with 6 patients experienced grade 3 to 4 irAEs and 1 patient developed fatal autoimmune hepatitis. These results suggest that salvage anti-CTLA-4 could potentially be another option for patients who progressed on prior immunotherapy, but the higher rates of high-grade irAEs may restrict their widespread use in the clinic.

6Local or locoregional treatment in patients with oligoprogressive diseaseRadiological progression on systemic treatment in patients with HCC can be classified into intrahepatic growth (IHG), new intrahepatic lesions (NIH), extrahepatic growth (EHG), new extrahepatic lesions (NEH) and new vascular invasion (nVI) [57]. These patterns of progression have been suggested to provide prognostic values and may aid in the design of clinical trials in HCC [57]. Interestingly, patients with NIH upon progression on immunotherapy tend to have improved survival compared to other patterns of progression [38]. One reason for this observation could be due to the availability of locoregional treatments for NIH. These NIH could be tackled by a variety of locoregional treatment such as radiofrequency ablation, external beam radiotherapy, or transarterial (chemo)embolization readily. Treatment of these resistant clones with locoregional therapies thus may improve survival by prolonging the use of systemic therapy.

Although the conventional classification of progression pattern may provide prognostic implications, it does not capture the tumour burden of progression, which is important in deciding whether locoregional therapies should be offered, or switching systemic therapies would be more beneficial. A relatively novel concept known as oligoprogression that describes the phenomenon of an overall responding or stable disease on systemic therapy apart from a limited number, typically 3 to 5, of lesions showing discordant progression [58]. This phenomenon is commonly reported in lung cancer [59], colorectal cancer [60], and prostate cancer [61], but it is less described in HCC. Treating oligoprogression may be of particular benefit in HCC given the possibility of second primary tumors to arise due to the field effect of underlying hepatitis and cirrhosis, as well as the genomic divergence between the primary and metastasis [62,63]. suggesting the potential for differential response to immunotherapy in different disease clones and the addition of local treatment to resistant clones could be a reasonable approach.

It has become clear that about 20 to 30 % of patients with advanced HCC who progressed on immunotherapy would be eligible for some forms of local or locoregional treatments (Table 2) [25,64]. For example, in the recently announced CheckMate-9DW trial, among patients who progressed on nivolumab plus ipilimumab, 21 (6 %) patients received subsequent radiotherapy, 12 (4 %) received subsequent surgery, and 29 (9 %) patients received locoregional therapies [11] In a recent retrospective study from Taiwan, about 30 % of patients with HCC who achieved durable response from immunotherapy initially followed by oligoprogression were eligible for local or locoregional therapies [25].

Evidence in the treatment of oligometastatic or oligoprogressive HCC are emerging. In the first case series that reported the treatment outcome of utilizing locoregional therapy to tackle oligoprogression, five patients with very advanced HCC, including the presence of extrahepatic metastases or major portal vein tumour thrombosis, were treated with radiotherapy to intrahepatic oligoprogressive sites while continuing immunotherapy. This treatment strategy has resulted in improvement in survival (median OS ∼ 24 months) compared to historical cohorts [24,65]. The Taiwan retrospective study also reported patients with oligoprogression who received locoregional therapies achieved a longer median OS compared to those without (46.2 versus 22.2 months) [25]. In another prospective phase II study that examined the use of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) in 40 patients with oligometastatic HCC, the median PFS was 5.3 months, and the 2-year OS was 80 %. Overall ORR of the treated lesions was 75.8 % and DCR was 98.4 %. Of note, 24 (60 %) patients received systemic treatment concurrently or sequentially with SBRT. Among these patients, 4 (10 %) patients received immunotherapy alone or immunotherapy combination, with another 18 (45 %) patients received MKIs. Overall, the delivery of SBRT to oligometastatic sites appeared to be safe and only 5 (12.5 %) patients experienced SBRT-related adverse events.

7Conclusion and future directionsThe treatment landscape for patients with advanced HCC has been transformed by the introduction of immunotherapy. In the era of MKIs, durable responses and long term survivors were rarely seen. However, with immunotherapy, about 20 % to 30 % of patients would response to treatment and up to 25 % of patients could survive beyond 4 years. Despite remarkable improvement in survival, more than half of them would progress on immunotherapy within 6 months and about 10 to 20 % of patients discontinued immunotherapy due to toxicity. The optimal subsequent management after progression on immunotherapy has become a therapeutic challenge and an unmet clinical need (Fig. 2).

As 40 to 50 % of patients with advance HCC who progressed on immunotherapy are still eligible for subsequent systemic treatments, evidence-based guidance on subsequent therapies is urgently needed. MKIs such as sorafenib and lenvatinib are generally recommended after progression on first-line immunotherapy. These agents demonstrated similar efficacy and safety compared to their respective first-line setting. However, prospective data with these agents are not available. The recent prospective phase II trials have provided evidence to additional agents such as cabozantinib and regorafenib which are of similar efficacy in the post-immunotherapy setting. At the moment, a number of phase II trials are ongoing (Table 4) and they will provide additional evidence on MKIs in this setting.

Retrospective studies have suggested that additional of anti-CTLA-4, an immune checkpoint inhibitors that acts on the priming phase of the cancer immunity cycle may salvage patients who progressed on anti-PD-(L)1 therapy. These data provided support for continuation of immunotherapy beyond progression, or in patients who were not fit for further agents with anti-VEGF properties, such as bleeding events. There were also evidence to suggest that molecular-directed therapy such as the use of everolimus in patients with inactivating mutations along the mTOR pathway or TSC1/2 gene may lead to response and improve survival. But this strategy remain exploratory without a well-conducted phase II or III trials in genomically enriched population.

Oligoprogression represents a form of progression following immunotherapy that were seen in about 20 to 30 % of patients. These patients should be considered for the opportunities of local or locoregional therapies such as with TACE or SBRT to those resistant clones, and continue on the immunotherapy because majority of the disease sites are still responding systemic therapy. Retrospective studies have shown that selected patients treated with this strategy has prolonged survival, and the concomitant use of local therapies and systemic treatments appear to be safe. However, prospective trials are lacking and should be a priority for future research.

To conclude, treatment landscape in advanced HCC is rapidly changing, not only in the first-line setting but also in the subsequent line setting. Multiple strategies are available for patients who progressed on first-line immunotherapy but the evidence that guides the optimal choice of subsequent therapies remain limited. A key element in the formulation of management decision thus is to discuss complex cases in the multidisciplinary team meeting (MDT), considering patients’ performance status, liver function, and comorbidities. The MDT also enables experts of different fields to share experiences and to comment on feasibility and practicality of each treatment options. The results of prospective trials are eagerly awaited to elucidate the optimal management options for patients who progressed on first-line immunotherapy.