Weekend admissions has previously been associated with worse outcomes in conditions requiring specialists. Our study aimed to determine in-hospital outcomes in patients with ascites admitted over the weekends versus weekdays. Time to paracentesis from admission was studied as current guidelines recommend paracentesis within 24h for all patients admitted with worsening ascites or signs and symptoms of sepsis/hepatic encephalopathy (HE).

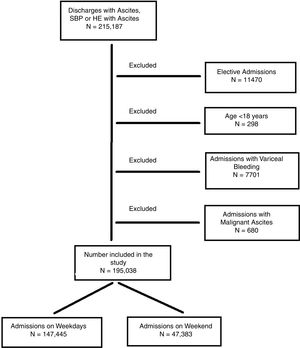

PatientsWe analyzed 70 million discharges from the 2005–2014 National Inpatient Sample to include all adult patients admitted non-electively for ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), and HE with ascites with cirrhosis as a secondary diagnosis. The outcomes were in-hospital mortality, complication rates, and resource utilization. Odds ratios (OR) and means were adjusted for confounders using multivariate regression analysis models.

ResultsOut of the total 195,083 ascites/SBP/HE-related hospitalizations, 47,383 (24.2%) occurred on weekends. Weekend group had a higher number of patients on Medicare and had higher comorbidity burden. There was no difference in mortality rate, total complication rates, length of stay or total hospitalization charges between the patients admitted on the weekend or weekdays. However, patients admitted over the weekends were less likely to undergo paracentesis (OR 0.89) and paracentesis within 24h of admission (OR 0.71). The mean time to paracentesis was 2.96 days for weekend admissions vs. 2.73 days for weekday admissions.

ConclusionsWe observed a statistically significant “weekend effect” in the duration to undergo paracentesis in patients with ascites/SBP/HE-related hospitalizations. However, it did not affect the patient's length of stay, hospitalization charges, and in-hospital mortality.

Cirrhosis is an increasing cause of morbidity and mortality, including in western countries. Ascites is the most common cause of hospital admissions and thus, contingent costs in patients with cirrhosis [1]. Management of ascites requires close monitoring and management by specialists who are proficient in procedures like paracentesis. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is one of the most common and dreaded complications of ascites, occurring in 25% of patients and is fatal in 30% [2,1]. For the timely diagnosis of SBP, a diagnostic paracentesis should be performed during index admission for all patients with ascites admitted to the hospital for evaluation and management of symptoms related to ascites or encephalopathy [3]. Data indicate that there are significant deficits in many aspects of the process of care of patients with cirrhosis. For example, a VA health system audit found that diagnostic paracentesis is done in less than 60% of indicated cases [4].

Differences in hospital staffing patterns and the lower availability of physicians and other support staff on weekends may have an impact on the outcomes in cirrhosis patients. Higher mortality for patients admitted to the hospital on the weekends than on weekdays for certain acute conditions, including upper GI bleeding, have been shown in several studies [5,6]. We aimed to examine whether admissions over the weekend had worse outcomes than weekdays for patients with cirrhosis and ascites.

2MethodsWe performed a retrospective, observational study using data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), an administrative database maintained by Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, consisting of all hospitalizations (until 2012) taken from a sample of 20% of the US hospitals, and then weighted so as to be nationally representative of all US hospitalizations [7].

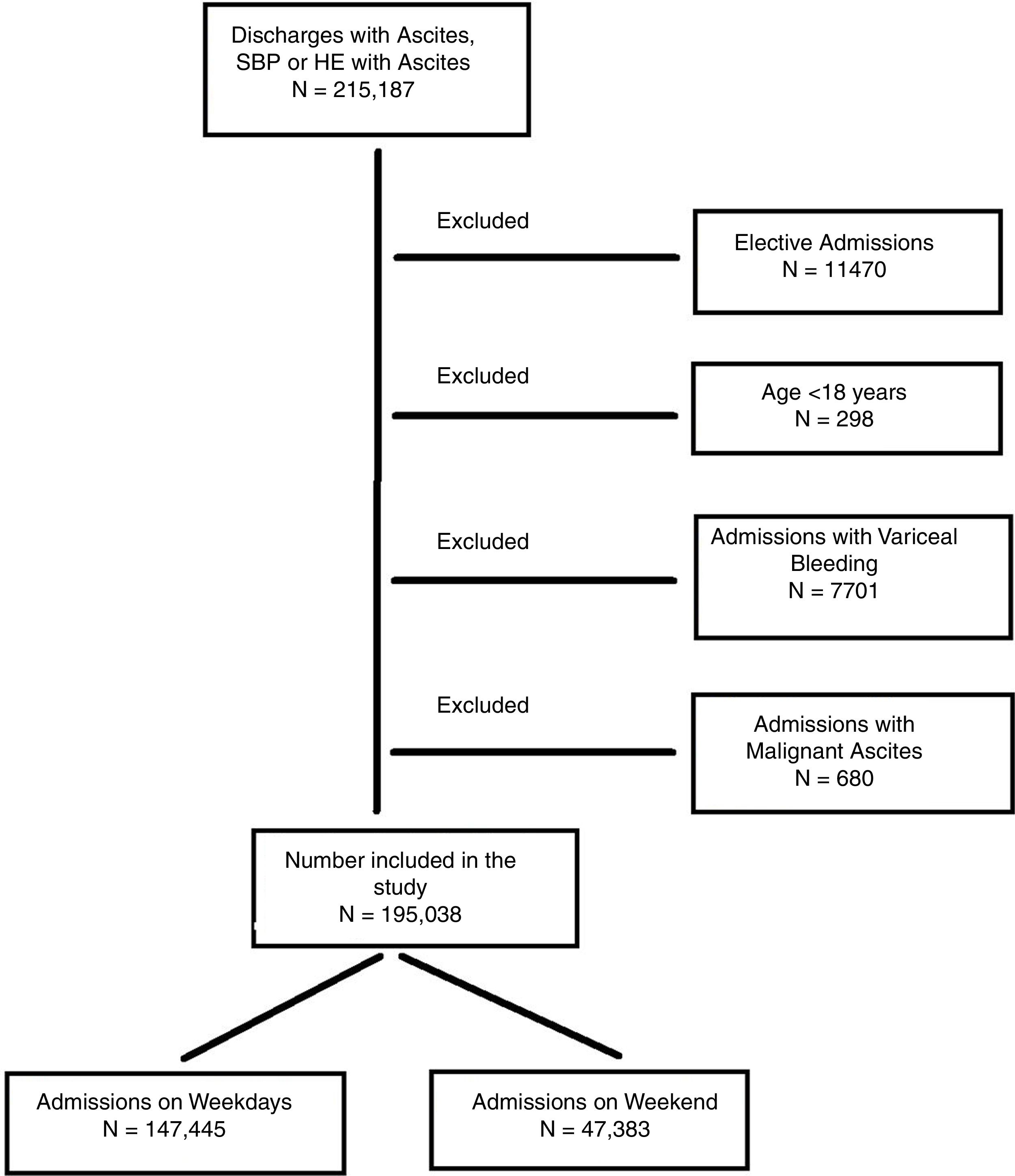

Our principal analysis included all hospitalizations with ascites (ICD 9 CM codes: 789.59) or SBP (567.23) as the first diagnosis. Patients with hepatic encephalopathy (572.2) as the primary diagnosis and a secondary diagnosis of ascites were included as well. To increase the specificity of the inclusion criteria, we required that all patients have a secondary diagnosis of cirrhosis (571.2, 57.15, 571.6). The study cohort and ICD-9 codes used have been previously validated [23]. We excluded patients who were less than 18 years old at the time of admission or who were transferred from another health facility to avoid misclassifying patients who had received a paracentesis before transfer. We further excluded the patients who were admitted electively to prevent skewing of data as elective admissions would be less frequent during weekends. Hospitalizations with variceal GI bleeding or metastatic ascites were also excluded since these patients receive prophylactic antibiotics and the management for ascites differs in these patients. Fig. 1 depicts the flow of the study cohort.

NIS database defines a weekend admission as one occurring between Friday midnight to Sunday midnight. We further calculate time to the procedure in days, as recorded in NIS. Hence, an appropriate paracentesis, i.e. within 24h as if it was done on day 0, or day 1 from the day of admission.

2.1Outcomes variablesOur primary outcome of interest was all-cause in-hospital mortality and all-complication rates. Major in-hospital complications were recorded including cardiogenic shock, respiratory failure requiring ventilation, septic shock, anemia requiring transfusion and acute kidney injury/hepatorenal syndrome, along with complications related to paracentesis like abdominal hemorrhage and hemoperitoneum in patients who underwent paracentesis. Secondary outcomes were (a) proportion of admissions in which an in-hospital paracentesis was performed, (b) early paracentesis (within 24h of admission) was performed, (c) healthcare total hospital charge (THC) and (d) duration of hospitalization (LOS in days), which were all encoded in the data set as unique variables.

2.2Statistical analysisOdds ratios for the primary outcomes were calculated by multivariate regression analysis. Baseline demographics and significant comorbidities based upon previous literature were examined as potential confounders by univariate regression with a cutoff p-value of 0.05. The significant factors were further forced into the multivariate regression model. Logistic regression was used for binary outcomes, and linear regression was used for continuous outcomes.

In order to identify if any missing data may change the results, we utilized multivariate imputation by chained equations (i.e., MICE) method. In the MICE model, first data was assumed to be missing at random, and then the package creates multiple imputations (replacement values) for multivariate missing data. The method is based on Fully Conditional Specification, where each incomplete variable is imputed by a separate model [8]. Results with and without imputation were not meaningfully different. Thus, results without imputation are reported. Data were analyzed using Stata 15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

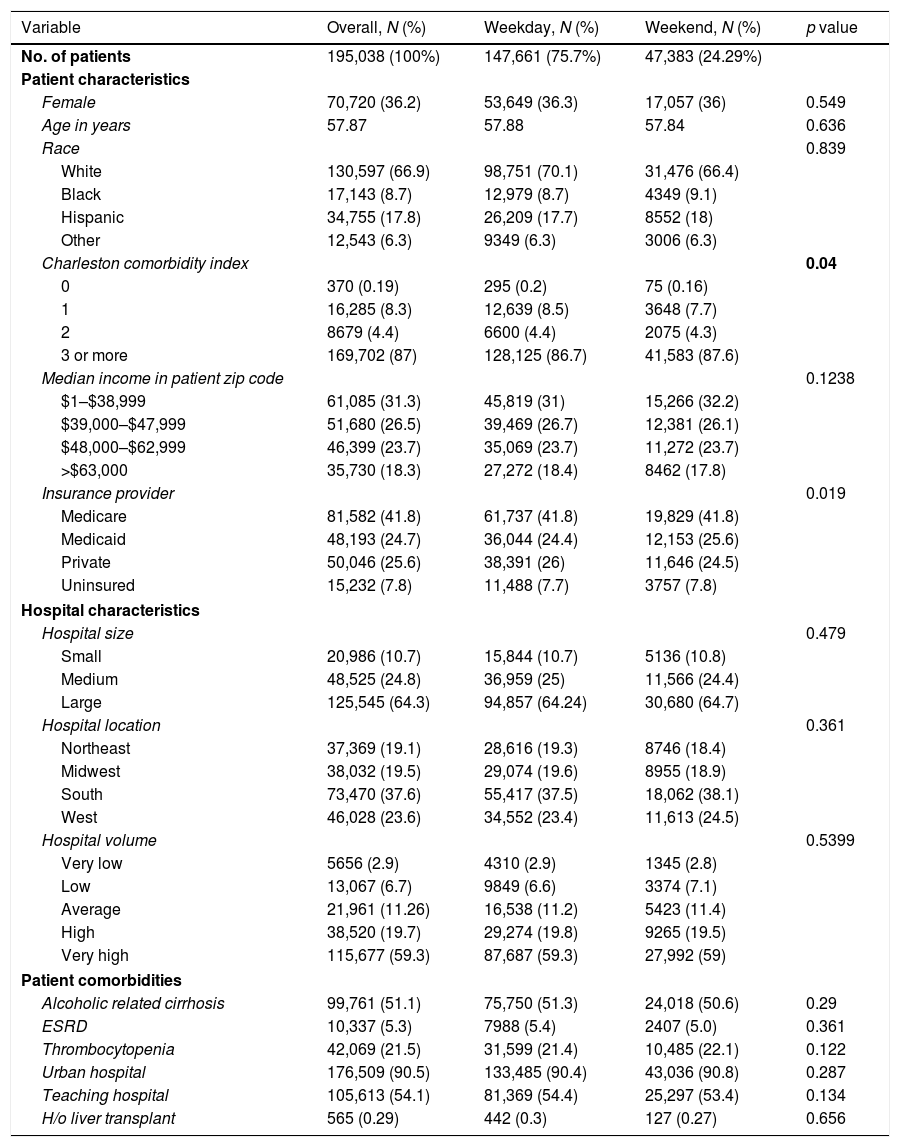

3ResultsBetween January 2005 to December 2014, a total of 78 million patients were discharged from the studied US hospitals, out of which 0.25% or 195,038 patients were admitted with ascites with cirrhosis and met our inclusion criteria. Of these, 147,655 (75.7%) were admitted on a weekday, while 47,383 (24.2%) occurred over the weekend. Table 1 presents a comparison of all hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of ascites with cirrhosis, stratified by admission on the weekend. Overall, the mean age of the population was 57.8 years, and this was no different between the two groups. Weekend and weekday hospitalizations were not changed for sex, race, median income, or hospital factors like hospital size, academic status, or hospital volumes. Patients admitted over the weekends were more likely to be sicker having a Charlson comorbidity index score of >3 (87.6% vs. 86.7%, p=0.04) compared with those admitted during the week. Weekend patients were more likely to have Medicare (25.6% vs. 24.4%, p=0.01) or be uninsured (7.8% vs. 7.7%, p=0.019) compared with those admitted during weekdays. Although these differences were statistically significant, the absolute differences were small. Finally, there were no differences amongst the two groups in the number of patients with a history of a liver transplant, end-stage renal disease, thrombocytopenia, or alcoholic cirrhosis.

Patient and hospital baseline characteristics.

| Variable | Overall, N (%) | Weekday, N (%) | Weekend, N (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 195,038 (100%) | 147,661 (75.7%) | 47,383 (24.29%) | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Female | 70,720 (36.2) | 53,649 (36.3) | 17,057 (36) | 0.549 |

| Age in years | 57.87 | 57.88 | 57.84 | 0.636 |

| Race | 0.839 | |||

| White | 130,597 (66.9) | 98,751 (70.1) | 31,476 (66.4) | |

| Black | 17,143 (8.7) | 12,979 (8.7) | 4349 (9.1) | |

| Hispanic | 34,755 (17.8) | 26,209 (17.7) | 8552 (18) | |

| Other | 12,543 (6.3) | 9349 (6.3) | 3006 (6.3) | |

| Charleston comorbidity index | 0.04 | |||

| 0 | 370 (0.19) | 295 (0.2) | 75 (0.16) | |

| 1 | 16,285 (8.3) | 12,639 (8.5) | 3648 (7.7) | |

| 2 | 8679 (4.4) | 6600 (4.4) | 2075 (4.3) | |

| 3 or more | 169,702 (87) | 128,125 (86.7) | 41,583 (87.6) | |

| Median income in patient zip code | 0.1238 | |||

| $1–$38,999 | 61,085 (31.3) | 45,819 (31) | 15,266 (32.2) | |

| $39,000–$47,999 | 51,680 (26.5) | 39,469 (26.7) | 12,381 (26.1) | |

| $48,000–$62,999 | 46,399 (23.7) | 35,069 (23.7) | 11,272 (23.7) | |

| >$63,000 | 35,730 (18.3) | 27,272 (18.4) | 8462 (17.8) | |

| Insurance provider | 0.019 | |||

| Medicare | 81,582 (41.8) | 61,737 (41.8) | 19,829 (41.8) | |

| Medicaid | 48,193 (24.7) | 36,044 (24.4) | 12,153 (25.6) | |

| Private | 50,046 (25.6) | 38,391 (26) | 11,646 (24.5) | |

| Uninsured | 15,232 (7.8) | 11,488 (7.7) | 3757 (7.8) | |

| Hospital characteristics | ||||

| Hospital size | 0.479 | |||

| Small | 20,986 (10.7) | 15,844 (10.7) | 5136 (10.8) | |

| Medium | 48,525 (24.8) | 36,959 (25) | 11,566 (24.4) | |

| Large | 125,545 (64.3) | 94,857 (64.24) | 30,680 (64.7) | |

| Hospital location | 0.361 | |||

| Northeast | 37,369 (19.1) | 28,616 (19.3) | 8746 (18.4) | |

| Midwest | 38,032 (19.5) | 29,074 (19.6) | 8955 (18.9) | |

| South | 73,470 (37.6) | 55,417 (37.5) | 18,062 (38.1) | |

| West | 46,028 (23.6) | 34,552 (23.4) | 11,613 (24.5) | |

| Hospital volume | 0.5399 | |||

| Very low | 5656 (2.9) | 4310 (2.9) | 1345 (2.8) | |

| Low | 13,067 (6.7) | 9849 (6.6) | 3374 (7.1) | |

| Average | 21,961 (11.26) | 16,538 (11.2) | 5423 (11.4) | |

| High | 38,520 (19.7) | 29,274 (19.8) | 9265 (19.5) | |

| Very high | 115,677 (59.3) | 87,687 (59.3) | 27,992 (59) | |

| Patient comorbidities | ||||

| Alcoholic related cirrhosis | 99,761 (51.1) | 75,750 (51.3) | 24,018 (50.6) | 0.29 |

| ESRD | 10,337 (5.3) | 7988 (5.4) | 2407 (5.0) | 0.361 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 42,069 (21.5) | 31,599 (21.4) | 10,485 (22.1) | 0.122 |

| Urban hospital | 176,509 (90.5) | 133,485 (90.4) | 43,036 (90.8) | 0.287 |

| Teaching hospital | 105,613 (54.1) | 81,369 (54.4) | 25,297 (53.4) | 0.134 |

| H/o liver transplant | 565 (0.29) | 442 (0.3) | 127 (0.27) | 0.656 |

Significant P Value are in bold

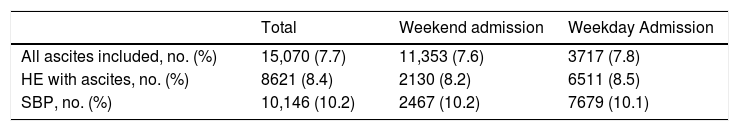

The total mortality rate for patients admitted with ascites was 7.7%, as described in Table 2. On univariate regression, weekend admission was not an independent predictor of overall in-hospital mortality compared with weekday admission (adjusted OR 1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.94–1.15). Even on multivariate regression after adjusting for the variables associated with higher inpatient mortality on univariate analysis (history of alcohol abuse, history of end stage renal disease, history of coagulopathy, admitted to medium and large size hospitals, older age), weekend admissions was not an independent predictor of death (adjusted OR 1.12; 95% CI 0.91–1.23). Similarly, on subgroup analysis, weekend admissions did not produce worse outcomes with regards to inpatient mortality for SBP patients (OR 0.99; 95% CI 0.94–1.04) or hepatic encephalopathy with ascites (OR 1.02; 95% CI 0.97–1.08).

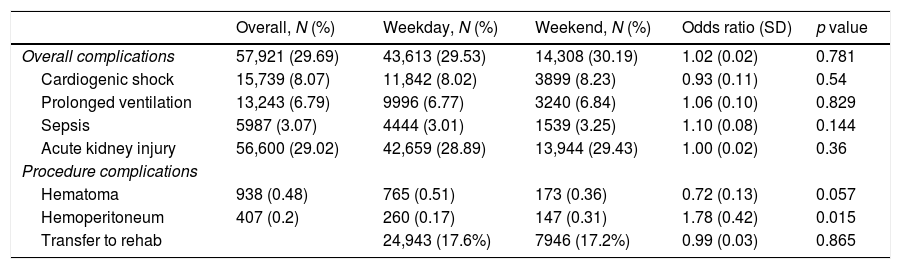

In the total cohort of ascites patients, 29.6% or 57,921 developed major complications (Table 3). Day of admission was not a significant predictor of total complication rates (adjusted OR for weekday admission vs. weekend admission: 0.60, 95% confidence interval 0.28–1.30). Weekend admissions were not found to be predictors for any major complications studied: cardiogenic shock (aOR 0.93; 95% CI 0.73–1.18), respiratory failure requiring invasive ventilation (aOR 1.06; 95% CI 0.88–1.27), sepsis (aOR 1.10; 95% CI 0.96–1.25), requirement of blood transfusion (aOR 1.04; 95% CI 0.98–1.11) and acute kidney injury or hepatorenal syndrome (aOR 1.03; 95% CI 0.95–1.05). However, weekend admission was a significant factor in the rate of hemoperitoneum in patients undergoing paracentesis (OR 1.83; 95% CI 1.49–2.25). On univariate analysis, factors associated with increased complications rates were patients advanced age, higher comorbidity index, possessing Medicare or private insurance, having thrombocytopenia on admission and admission to hospitals affiliated with academic institutions (all p<0.01).

Total in-hospital complication rates.

| Overall, N (%) | Weekday, N (%) | Weekend, N (%) | Odds ratio (SD) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall complications | 57,921 (29.69) | 43,613 (29.53) | 14,308 (30.19) | 1.02 (0.02) | 0.781 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 15,739 (8.07) | 11,842 (8.02) | 3899 (8.23) | 0.93 (0.11) | 0.54 |

| Prolonged ventilation | 13,243 (6.79) | 9996 (6.77) | 3240 (6.84) | 1.06 (0.10) | 0.829 |

| Sepsis | 5987 (3.07) | 4444 (3.01) | 1539 (3.25) | 1.10 (0.08) | 0.144 |

| Acute kidney injury | 56,600 (29.02) | 42,659 (28.89) | 13,944 (29.43) | 1.00 (0.02) | 0.36 |

| Procedure complications | |||||

| Hematoma | 938 (0.48) | 765 (0.51) | 173 (0.36) | 0.72 (0.13) | 0.057 |

| Hemoperitoneum | 407 (0.2) | 260 (0.17) | 147 (0.31) | 1.78 (0.42) | 0.015 |

| Transfer to rehab | 24,943 (17.6%) | 7946 (17.2%) | 0.99 (0.03) | 0.865 | |

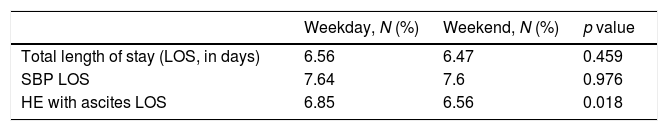

Weekend admissions as compared to weekday admission are not a predictor of increased resource utilization, namely length of stay in days (6.4 days vs. 6.5 with adjusted regression coefficient 0.12, 95% CI −0.23 to 0.49), total hospitalization charges in US$ (33,940 vs. 34,709 with adjusted regression coefficient −52, 95% CI −3006.498 to 2901.882) and total costs of hospitalization ($10,646 vs. $11,570; −$370, −$1274 to $649).

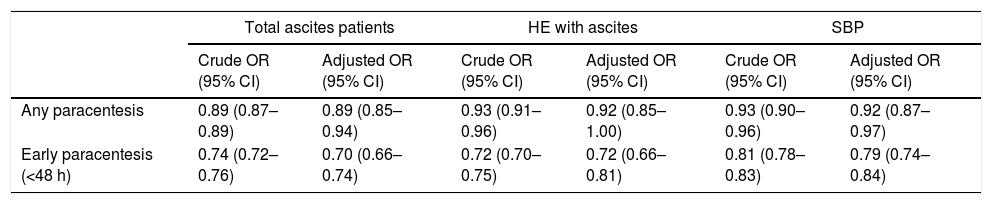

In-hospital paracentesis rates and time to paracentesis based on day of admission Table 4.

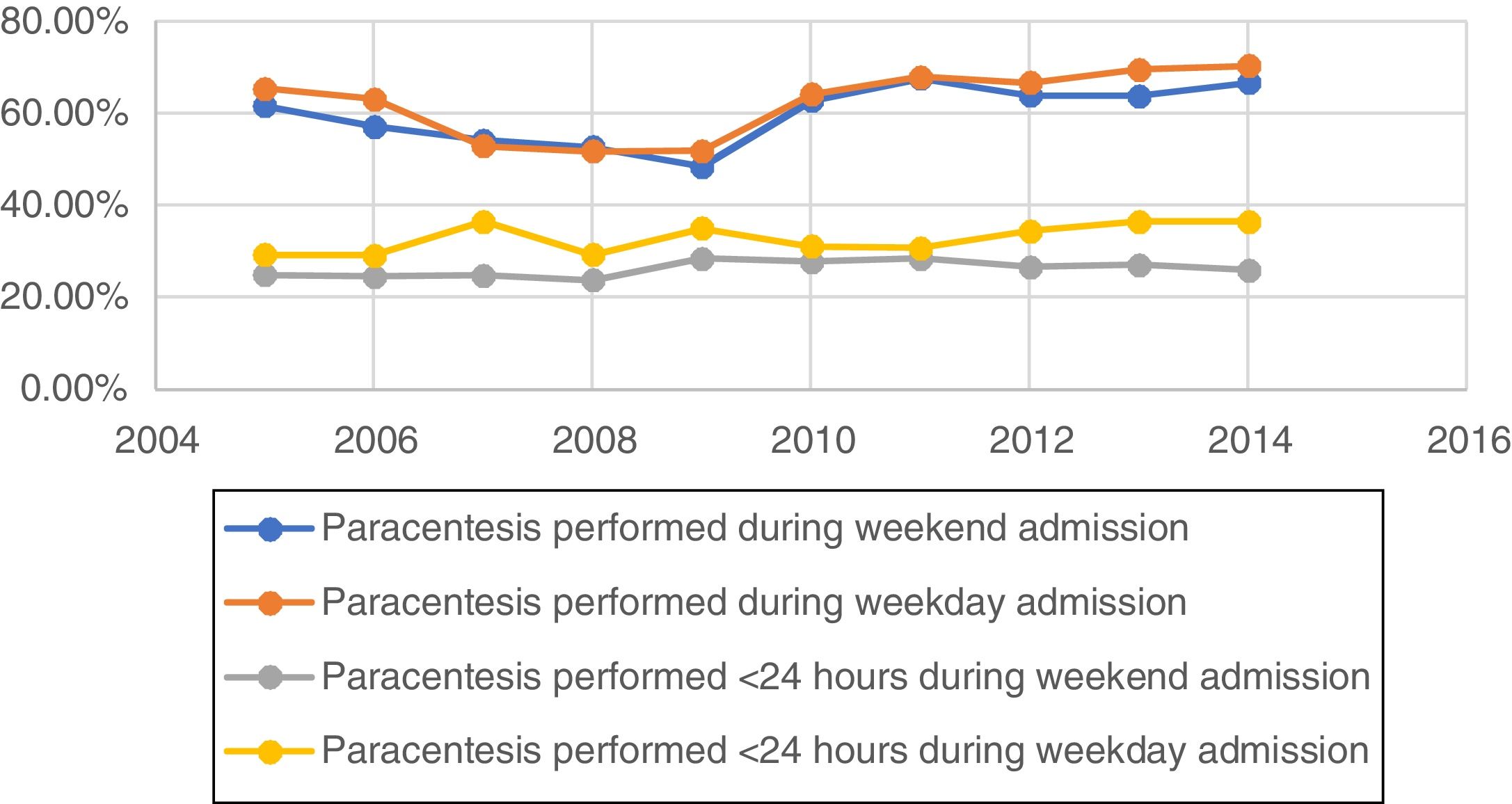

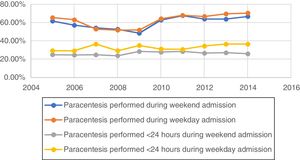

For all patients with ascites, only 62% underwent paracentesis during their total hospitalization, 31.2% underwent paracentesis within 24h and 42.2% underwent paracentesis within 48h. Patients admitted on the weekends were less likely to undergo paracentesis during their whole hospitalization (62.7% vs. 60.1%, adjusted OR 0.89; 95% CI: 0.87–0.89). The difference between paracentesis utilization was even more stark when early paracentesis was studied, as depicted in Table 5. Patients admitted over the weekend were less likely to undergo paracentesis within 24h of presentation (32.8% vs. 26.3%, adjusted OR 0.74; 95% CI: 0.72–0.76) or within 48h of admission (46.6% vs. 42.2%, adjusted OR 0.83; 95% CI: 0.81–0.85). The mean time to paracentesis for the weekend group was 2.92 days (±0.07 days) whereas for the weekday group was 2.67 days (±.04 days). Analyzing the rates of paracentesis from 2005 to 2012 showed a bimodal distribution in total paracentesis as shown in Fig. 2, with the trough in the year 2009. On dividing the study period from 2006 to 2014 in 3-year intervals, we found that the latest interval from 2012 to 2014 showed significantly higher total paracentesis rates, for both weekdays and weekend admissions, and early paracentesis rates for weekday admissions than the other 2 intervals. However, rates of early paracentesis rates for weekend admissions were significantly higher for the middle interval, from 2009 to 2011 and decreased from 2011 onwards.

Adjusted odds ratio of the procedure being done on weekends compared with weekdays.

| Total ascites patients | HE with ascites | SBP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Any paracentesis | 0.89 (0.87–0.89) | 0.89 (0.85–0.94) | 0.93 (0.91–0.96) | 0.92 (0.85–1.00) | 0.93 (0.90–0.96) | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) |

| Early paracentesis (<48 h) | 0.74 (0.72–0.76) | 0.70 (0.66–0.74) | 0.72 (0.70–0.75) | 0.72 (0.66–0.81) | 0.81 (0.78–0.83) | 0.79 (0.74–0.84) |

The ‘weekend effect’ describes poorer outcomes and increased adverse events for patients being admitted on weekends for specific conditions such as upper gastrointestinal bleeding, myocardial infarction, ruptured aortic aneurysm, pulmonary embolism, or stroke [9–12]. Current evidence attributes the poorer outcomes on the weekend to possible factors such as limited resources in hospital staffing to carry the same workload compared with weekdays [13], healthcare providers are less experienced [14], specialists such as gastrointestinal subspecialists and proceduralists, mainly interventional radiologists are limited [15], and continuity of care is reduced [16]. Another possibility is that patients admitted on the weekend might have a more severe illness with increased comorbidities [17], as supported by our study, which showed the patients admitted over the weekend had higher comorbidity burden and were more likely to require intensive unit care. Nevertheless, another study found that a higher Charlson comorbidity score was not associated with a significant weekend effect after adjusting for comorbidity [18]. It is also plausible that patients with minor symptoms, like abdominal distention not causing respiratory distress, would be more inclined to wait over the weekend and see their primary caretaker the following day. A study in the United States reported that patients are admitted on the weekend at a lower rate than on weekdays [19].

In-hospital mortality did not differ between patients hospitalized on weekends versus weekdays for ascites with liver cirrhosis. Similarly, weekend admission was not an independent predictor of total complication rates, hospitalization charges, hospitalization cost or length of stay. On further subgroup analysis, no link was obtained between weekend admission and of any of these outcomes in patients with SBP or hepatic encephalopathy. Factors associated with increased complication rates were advanced age, higher comorbidity index, possessing Medicare or private insurance, having thrombocytopenia on admission and admission to hospitals affiliated with academic institutions, but weekend admissions were not one of them. To our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the weekend effect in patients with cirrhosis and presenting with ascites. Since patients with ascites, SBP or hepatic encephalopathy often have more risk factors, such as more severe liver disease estimated by the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score [20], portal hypertension, hepatocellular carcinoma, and circulatory dysfunction [21], the time of admission played only a small role in mortality.

Patients admitted on weekends with ascites were less likely to undergo an early paracentesis (<24h of admission), or any paracentesis during their whole hospitalization. One study utilizing the US national database showed that paracentesis was associated with reduced mortality in patients, although the results were not significant when adjusted for confounders [22]. One explanation could be that the patients who are clinically suspected of having SBP may receive prophylactic antibiotics and albumin without performing a diagnostic paracentesis, thus obscuring any direct relationship between paracentesis and survival. However, this is not consistent with the best practices since some patients having SBP may be missed clinically. Delays/failure in performing paracentesis have been associated with increased mortality in patients with SBP [23]. One such study showed a 3.3% increase in mortality with delay of every hour in performing a paracentesis [24]. The delay and decreased rates of paracentesis could be because of safety concerns and the lack of support staff. Incidence of hemoperitoneum due to paracentesis performed over the weekend was almost double than the weekdays supports this notion.

One major factor for the delay in time to paracentesis is that many hospitalists do not perform paracentesis, despite it being delineated a core procedure that a hospitalist is likely to perform as per society of hospital medicine [25,26]. The possible main ground lies in the inadequate training and lack of confidence in doing bedside procedures of the recently graduated internal medicine residents [27,28]. In addition, a lesser number of work hours and the wider availability of other specialties such as interventional radiology may be included in the overall decline of certification rates in residents [29]. NIS does not contain data about the availability of specialists like interventional radiologists or gastroenterologists/hepatologists in each hospital. However, there are three indirect measure that can be used to determine the likelihood of availability of specialists. Those are teaching hospitals, hospital bed size and hospital volumes. None of these measures showed any difference in rates of paracentesis between weekends and weekdays. It is to be noted that our study showed paracentesis to be a safe procedure with the rates of complications, mainly abdominal hematoma, and hemoperitoneum, were less than 0.3%. Innovative training models such as resident driven procedure service and simulators have shown to significantly improve certification rates for paracentesis [29,30]. Rates of paracentesis have significantly increased overall from 2005 to 2012, but the rate of early paracentesis <24h have been unchanged over the study period. Since the publication of AASLD guidelines in 2012 recommending paracentesis in all patients with new ascites within 24h of admission, we have seen a steady increase in the rates of paracentesis in United States, increasing by 3.4% overall from 2012 to 2014.

The limitations of our study arise from the use of administrative data, which is vulnerable to potential misclassification of subjects and variables. To reduce the sampling bias, we used previously validated codes to define the study sample [31,32]. Our estimate of underutilization and delayed paracentesis should be reliable given coding for paracentesis had >80% sensitivity [33]. Patients with insignificant ascites seen on imaging only might have been incorrectly included in the study. Second, because of the administrative nature of our database, we could not use liver disease severity scales such as MELD scoring or the grade of ascites to account for the decision to perform paracentesis. Still, we were able to apply a validated general prognostic scale, the Charlson comorbidity index. It is a common perception that severely ill patients may not receive a paracentesis because of calculated risks, coagulopathy, or futility. However, Kanwal et al. found that patients with worse liver disease were more likely to receive the recommended ascites care [4]. Third, our study was technically limited to accurately capture patients who developed ascites after admission. However, inpatient development of ascites is commonly reported in postoperative patients undergoing liver transplantation, which formed a tiny percentage of our study sample [34]. Fourth, since the exact cause of death is not captured in the NIS. However, previous literature studying the weekend effect has also examined the all-cause mortality rates [9–11]. Finally, ours was an observational study and the association between day of admission and early paracentesis rates should be viewed with caution. The hypothesis can be a basis for future randomized trials to allow definitive conclusions concerning this relationship to be drawn.

5ConclusionsCases with cirrhosis who are hospitalized with ascites have comparable in-patient mortality rates, total complication rates, hospitalization charges and hospitalization length, regardless of the time of admission whether on weekends or on weekdays. However, those who are presenting on the weekends, are comparatively less likely to undergo a paracentesis within 24h from admission or during their complete hospitalization.AbbreviationsAASLD

American Association for Study of Liver Diseases

HEhepatic encephalopathy

NISNational Inpatient Sample

SBPspontaneous bacterial peritonitis

ORodds ratio

VA health systemVeterans Affairs health system

MICEmultivariate imputation by chained equations

THCtotal hospital charge

MELDmodel for end-stage liver disease

Ethical approvalThis article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consentInformed consent was not required as the study contains deidentified patient data, individual participants were not contacted and no intervention was performed.

Financial supportThe authors declare that there was no grant or financial support received whatsoever for the research conducted by us and writing of this article.

Conflict of interestAll the listed authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.