Introduction

A recent study quoted that approximately 30 000 people/year survive an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in Spain and they go on to join the number of candidates for the secondary prevention of ischaemic heart disease (IHD).1 Many clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of certain treatments in the secondary prevention of IHD, such as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) and other platelet anti-aggregants, beta-blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin-II receptor antagonists (ARA-II) or statins.2-4 There is also a significant consensus on the importance of, advising against smoking, advice on exercise and diet.3,4

The National Health System (NHS) 2004-2007 Ischaemic Heart Disease Integral Plan (PICI, in Spain)5 pointed out the need to treat post-infarction patients with ASA, beta-blockers and statins in indicated cases; although the PICI commented on "insufficient" levels of these measures, it did not give any information on the magnitude of the problem of under treatment.5 The objective of this study is to give an approximation of IHD secondary prevention measures in the Spanish NHS from the results of the observational studies published in the last 10 years.

Methods

Design

Systematic review of the medical literature.

Population

Observational studies published between 1995 and 2004, carried out on patients with IHD in Spain, and which describe the use of certain secondary prevention measures (drug treatments and/or advice) at hospital discharge or in the follow-up after discharge, as well as whether the control was carried out in hospital outpatient clinics or in primary care. Studies which exclusively referred to management while in hospital were excluded.

Literature Search

A search was first carried out in the MEDLINE data base using key words such as, myocardial ischemia or myocardial infarction and the synonymous descriptors of the MeSH thesaurus for these 2 terms. The qualifiers, prevention and control and therapy were used and the search was limited to articles with a summary (to avoid selecting editorials or informative works) and carried out on humans. The search was also restricted to articles in Spanish or which made reference to Spain and published from 1995-2004. This search was completed by a search in the Doyma Publishing data base (using very different terms, giving the non-specificity of the search engine), which include the main cardiology, internal medicine and primary care journals in Spanish, consulting with experts and a manual review of the literature of selected studies and review articles on the subject.

Extraction of Data and Variables

Two of the authors independently reviewed the summaries, or, if necessary, the complete texts obtained from the different sources, and selected the studies that complied with the inclusion criteria. These studies were analysed, first by one author, who extracted data of interest, and then verified independently by a second author. In case of discrepancies, a consensus agreement was reached. The information extracted included, characteristics of the study (period, type of study, setting, follow-up time, location, number and characteristics of the selected population), treatment variables (anti-aggregants, lipid lowering drugs, beta-blockers, ACEI and ARA-II, calcium antagonists, nitrates, and anticoagulants) and interventions on lifestyles (anti-smoking, diet, and exercise advice). The information was collected as it was presented by the authors of each of the studies, usually as a percentage of patients to whom a determined intervention was administered. When clarification of any aspect was required, the authors of the original studies were consulted.

Analysis

A descriptive analysis of the results of the studies included was carried out. The lack of homogeneity between the studies and the time differences was not conducive to summarising the results using meta-analysis or other techniques. The time trends in the use of some drugs (ASA, beta-blockers, ACEI and ARA-II, and statins) were analysed by estimating the linear regression slope during the period reviewed.

In this analysis, and to avoid giving the same weight to studies of different sizes, the figures of each study were weighted by the number of cases included.

Results

A total of 22 studies6-27 that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were found (Table 1). The studies were published between 1996 and 2004, but the inclusion periods were from 1994 to 2003. Fifteen studies were in the hospital setting6,10-14,17-19,21,23-27 (of which 4 presented follow up data from outpatient clinics after the hospitalisation period10,13,21,24 and 1 was carried out by specialised care units26), and 7 were carried out in primary care7-9,15,16,20,22 (although one of them included data at discharge16). A cohort design was used in 13 studies and 9, including all of those from primary care, except PREMISE16 were cross-sectional designs.

Three studies included a care improvement intervention,19,21,27 therefore they could not be considered as strictly observational (although they were low intensity treatments, therefore it was eligible for inclusion in the study), and one was an observational type nested in a clinical trial.23

The majority of the studies included those discharged alive after admittance due to an AMI, although patients with different forms of IHD or post-surgical coronary were included in 12 studies. In a mixed study of primary and secondary prevention, only the data applying to the latter patients were included.26 The results obviously varied in setting and number of cases: from studies in only one primary care centre with less than 100 cases8,9 to studies with more than 100 hospitals21 or more than 2000 pacientes.14,18,19,21,25,27 In total, 33 808 patients on hospital discharge (mean of 1610 per study) took part, 5956 in outpatients follow-up (851 per study), and 1556 primary care (194 per study). As regards funding, 8 studies were exclusively financed by the pharmaceutical industry, 6 by a health administration (in 2 cases exclusively and 4 combined with the pharmaceutical industry or private funding), and in 8 the source of funding was not stated.

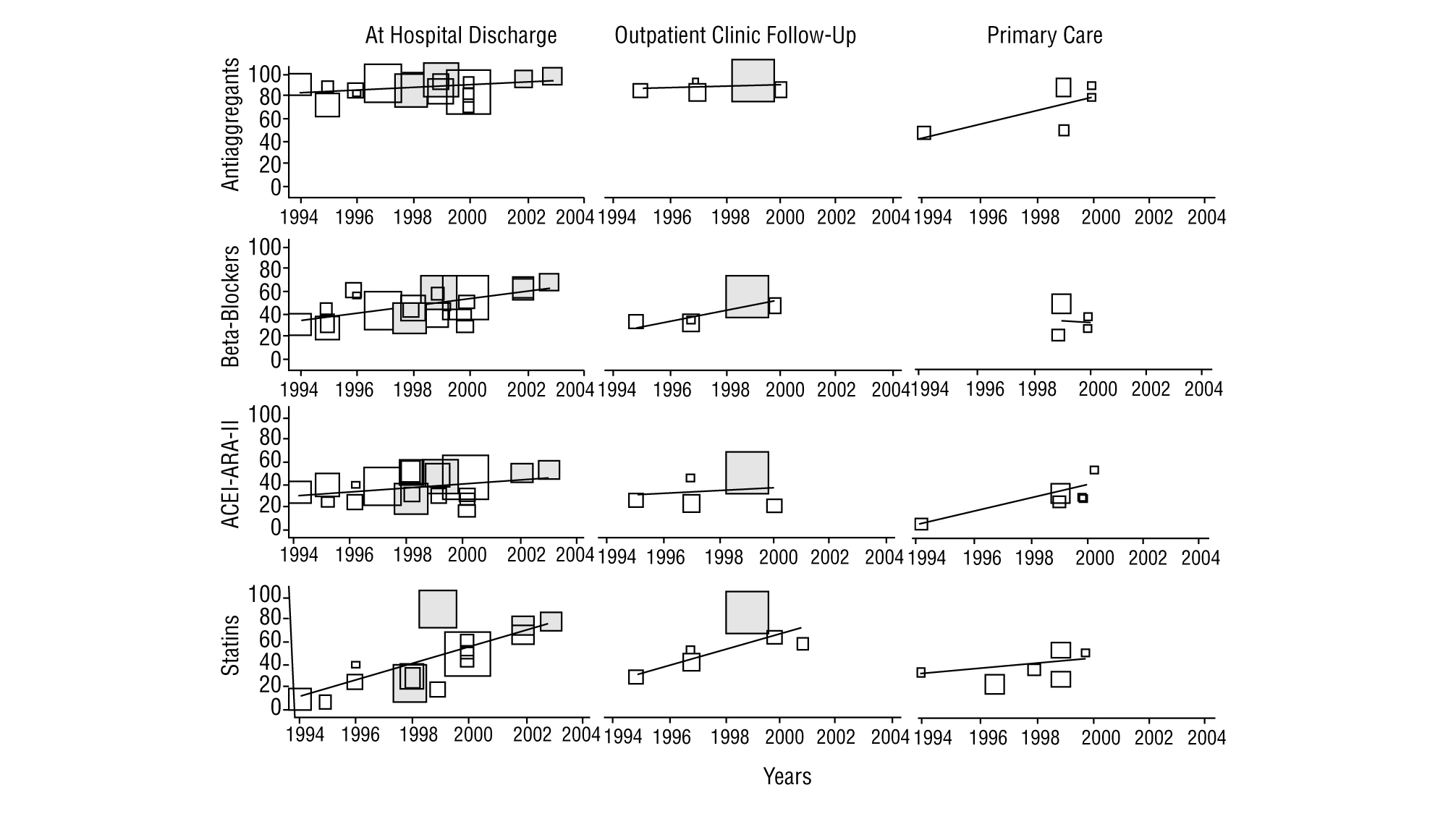

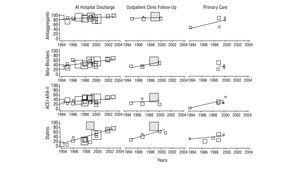

As regards the studies with data on discharge from hospital (Table 2, Figure 1), all except 212,23 exceeded 80% of patients on anti-aggregants. Four6,11,12,23 presented data with less than 35% of the patients on beta-blockers, while 6 exceeded 50%. Nine showed figures of less than 40% for patients treated with ACEI or ARA-II, and varied between 16% in EUROASPIRE-II24 and 52% in CAM.27 Lipid lowering drugs were mentioned in 12 studies, of which 5 of them pointed out a percentage use of less than 30%6,10,13,16,17; on the other hand, PRESENTE21 reported figures very close to 90%. Advice on diet was mentioned in 4 studies and anti-smoking and exercise advice in 3 of them. The percentages of patients advised were above 90%, except in one study,27 although in this case the advice mentioned in the discharge report, was assessed.

FIGURE 1 Time trends of the percentage of patients treated with the respective drug in studies on the secondary prevention of ischaemic heart disease. ARA-II indicates angiotensin II receptor antagonists; ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. The size of the symbols of each study is proportional to the number of patients included. The shaded blocks indicate intervention studies.

The figures on other treatments are also shown in Table 2, such as nitrates (from less than 10%27 to more than 80%13,16,17 depending on the different studies), calcium antagonists (from less than 5%27 to more than 40%13,23), and anticoagulants (from 6%21 to 8.6%24).

Of the 12 studies (5 hospital based and 7 carried out in primary care) with after discharge follow-up data (Table 3, Figure 1), 8 give anti-aggregant figures that, except in 2 studies with figures lower than 50%,7,20 are similar to those of studies at discharge. Beta-blockers (7 studies) have percentages of patients treated of between 34% and 59% for hospital based ones, and between 22% and 50% in primary care. As regards ACEI and ARA-II (8 studies), 5 studies state percentages around or below 25%,7,10,13,20,24 while another 2 exceeded 50%.9,21 With the lipid lowering drugs, the variation detected in the treatments at discharge are maintained, with figures that go from 89.5% in PRESENTE21 to around 25%.10,22 The nitrates, calcium channel antagonists and anticoagulants also maintain significant ranges of variation, similar, though not as wide as those in treatments at discharge, and only one study recorded different types of advice (rates of 100%, although referred to the population with the respective health problem).26

The time trends (Figure 1) of the treatment rates, show, on the whole, a significant increase in the use of statins and beta-blockers and, to a lesser extent in ACEI and/or ARA-II. ASA, based on the high figures, also shows a definite improvement. Two intervention studies,21,27 tend to maintain the highest treatment rates. The trends in primary care are difficult to interpret owing to the lack of studies and their concentration in the 1998-2000 period.

Discussion

On looking at the studies on hospital discharges, the results of this study show acceptable prescription percentages of anti-aggregants and a rapid and significant increase in the use of beta-blockers, ACEI and statins. Even so, there is room for improvement in the majority of the figures obtained, if we take the PRESENTE21 or CAM27 studies as a reference. It is possible that the improvements with time may have not been homogeneous, since the studies carried out in the 1999-2000 period, such as ICAR23 and EUROASPIRE II,24 show low rates of ACEI use (27% and 16%, respectively).

As regards nitrates and calcium antagonists, the figures are erratic, without any obvious time trend and, above all, without any clinical logic, especially as regards the relatively high use of calcium agonists in patients with AMI. The use of anticoagulants appears to have remained stable in the period. The scarcity of studies which give figures on anti-smoking, exercise and diet advice, means that trends cannot be interpreted. The studies carried out after hospital discharge, show a similar pattern to that discussed: acceptable rates of anti-aggregants and improvements in the use of beta-blockers, ACEI and statins, which are, however, lower than the follow up figures from PRESENTE21 or those established as possible by Brotons et al, on reviewing the

PREMISE28 patients. Aspects which suggest a significant room for improvement in care. The studies based in primary care, with two exceptions,9,16 show low treatment figures, although their characteristics (cross-sectional except in one case,16 with patients in different periods of follow up, lower sample size and without data on patients recruited after the year 2000), makes them difficult to interpret. In any case, the differences between the extra-hospital studies could be explained by: a) decrease in the intensity of treatment during the period studied, either due to withdrawals or because patients discharged years ago received less treatment at that time and the guidelines may not have been subsequently updated; in this event, the follow up windows used in hospital studies (usually 6 months) collected recent patients, while the cross-sectional designs of primary care would include patients at different periods of follow-up, and b) due to significant local and regional variations in the use of drugs, clearly demonstrated in some studies on the within-hospital management of AMI.25,29

The review carried out has important limitations in trying to specify the current situation of updates in secondary prevention of IHD, since there is no recent data and, as our own review shows, there have been significant improvements in the treatment percentages. This limitation could be even more important in primary care (studies with patients treated between 1994 and 1999). Similarly, and even with the exception of multicentre hospital studies, the studies combine restricted territorial settings and a significant variation, which makes it difficult to extrapolate to the whole NHS. Also, the particular design of the majority of studies, developed by professionals who take part in them voluntarily, where it is hoped that more interest is taken on the problem, leaves them open to the possibility of biases in the referred figures as regards those of the NHS overall.

In any case, the review carried out suggests that, along with significant advances in the pharmacological management of the secondary prevention of IHD, more evident in specialised care than primary care, there is still a lot of room for improving care, particularly as regards the under use of beta-blockers, ACEI and statins. Although it is anticipated that the current figures in primary care may be higher, partly because they have a close relationship with the prescription figures of the specialists and these have increased, to obtain information on the current situation in the management of these patients in primary care is a priority research objective where the analysis of determined sub-groups (by gender, age groups, diabetics and others) should not be forgotten. These investigations should also look into the analysis of the factors (of the patient, the doctor, the setting) associated with the sub-optimal management of the secondary prevention of IHD. The available data probably points to the urgency of starting improvement interventions in different settings, particularly in primary care.

Acknowledgements

The anonymous evaluators of the manuscript and for their suggestions and recommendations.

Spanish version available at www.atencionprimaria.com/141.944

A commentary follow this article (pág. 257)

This study forms part of a research project entitled "Impact of health care on health. Implications for the conciliation between technological innovation and sustainability of the state of well-being in Europe", financed by a research grant from the BBVA Foundation.

Conflict of interests: none in relation to this study.

Correspondence:

S. Peiró.

EVES. Juan de Garay, 21. 46017 Valencia. España.

E-mail: peiro_bor@gva.es

Manuscript received October 27, 2005.

Manuscript accepted for publication January 2, 2006.