The impact of the Social Determinants of Health (SDH) needs to be analyzed. Upon evaluating SDH in developed countries, we observed broad differences. Mexico, compared with countries belonging to the Organization for Cooperation and Economic Development (OCED), shows low ratings in many of the indicators for childhood well-being.

On the positive side, our international position has improved as well as revealing significant deficiencies. Emphasis is placed on the impact of SDH on both rural and urban localities where there are areas of opportunity to improve the conditions of children. In the context of Latin American and the Caribbean, some countries demonstrate better performance than Mexico.

In Mexico, important differences exist according to various indicators of childhood well-being in both rural and urban areas where there are still major shortcomings: the childhood population with disabilities, the family composition, the right to autonomy, the actual health conditions, education, poverty, housing, child labor and the regulation and protection of rights provided by the government.

Therefore, Mexico requires strengthening of all actions within the shortest time possible in order to achieve standards equal to other OECD countries. Essential to this is a strong, close and simultaneous collaboration among the public sectors to impact on deficiencies in education, housing, safety and health conditions of the various localities, among others.

El impacto de los Determinantes Sociales de la Salud (DSS) en los niños requiere ser analizado. Al evaluar los DSS en países desarrollados se observan amplias diferencias que deben ser analizadas. México, comparado con los países de la Organización por la Co-operación y el Desarrollo Económico (OCDE), muestra bajas calificaciones en la mayoría de los indicadores de bienestar infantil.

Si bien nuestra posición internacional ha mejorado, aún revela importantes deficiencias. Destaca el impacto que los DSS tienen tanto en los ámbitos rurales como en los urbanos, en los que existen áreas de oportunidad para mejorar las condiciones de los niños. En el contexto Latinoamericano y del Caribe también existen algunos países con mejor desempeño que el nuestro.

En México existen importantes diferencias en varios indicadores de bienestar infantil entre las entidades federativas, como la proporción de comunidades rurales y urbanas, la situación de la población infantil con discapacidad, la composición de las familias, el ejercicio del derecho a la identidad, las condiciones propias de la salud, la educación, la pobreza, la vivienda, el trabajo infantil y la regulación y protección del Estado sobre estos derechos.

Por lo anterior, México requiere reforzar todas aquellas acciones que permitan, en el menor tiempo posible, lograr resultados más cercanos a los estándares del resto de los países de la OCDE. Para ello es indispensable una firme, estrecha y simultánea colaboración entre los sectores públicos, que incidan en las deficiencias en educación, vivienda, seguridad y condiciones sanitarias de las localidades, entre otras.

1. Social Determinants of Health

Existing inequities in a same population favor that certain groups of the population have less access to formal education, jobs and adequate remuneration. Also, they are born and live in disadvantage. In the case of health, these disadvantages encourage diseases and death at higher rates than the rest of the population living under more favorable conditions.1 This association is identified through the cycle of life and paradoxically what was thought a few decades ago, social and health inequities still exist in developed or "rich" countries. Regardless of the fact that they have universal systems of education and health, these contrasts remain and, in some cases, increase.2,3

A significant number of health problems can be attributed to socioeconomic conditions of a population, but it is also true that health policies have focused on the application of curative strategies. In addition, those countries that have incorporated redistributive social and economic policies and formal employment have achieved success in improving the health of the population and reducing inequalities. Such policies have been driven since the 1980s by the World Health Organization (WHO).4

As the concept spread, a large number of countries began to apply research models on the impact of social determinants of health (SDH) in different population groups and throughout the life cycle. One of the pioneering models of SDH—and frequently used as a theoretical basis in case studies—is the Rainbow Model by Dahlgren and Whitehead.5 This model places the individual and the sociodemographic characteristics in the center and around the over lapping groups of determinants: lifestyle, social networks, living and working conditions and, finally, socioeconomic, cultural and environmental conditions. This approach clearly distinguishes multiple social factors to which individuals are exposed. At the center of this representation are the biological and inherited attributes.

Regarding the SDH, the most recent work with a wider dissemination originated from the WHO. It analyzed the favorable impact of actions aimed at reducing the effect of some SDH in studies in different countries and formed in 2005 the Commission on Social Determinants of Health composed of decision-makers and government officials, scientists, expert groups and members of society who developed recommendations based on evidence on interventions and policies supported on social determinants in order to improve health and reduce inequities.6

SDH were divided into "structural" and "intermediaries." In the first, at a macro-level, it is recognized as a starting point for a broad socioeconomic and political context, whereas at the micro- or individual level it includes education, employment and income factors, among others. On the other hand, "intermediary" determinants include biological factors, lifestyle, living conditions and the health system responsible for providing those services.

Years later, the Commission published a report whose general recommendations were to carry out specific actions to improve living conditions with particular emphasis on priority groups such as early childhood; to develop social protection policies; create conditions that allow successful aging; fight against the unequal distribution of power, money and resources; and establish or strengthen surveillance systems for health equity. The report also exposes the fact that interventions in the "non-health" or outside the sector are needed to improve health outcomes and achieve health equity within and among nations.6

In order to show the results of the work of different countries in regard to the elimination of health inequities and to address the SDH, in 2011 the World Meeting on Social Determinants of Health was held (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 21-26 October 21-26, 2011), organized by the WHO. Hence arose the document "Closing the gap: policy into the practice on social determinants of health. Discussion Paper." The main theme was the commitment of States to work in the five core subjects: adopt improved governance for health and development, promote participation in policy-making and implementation, further reorient the health sector towards promoting health and reducing health inequities, strengthen global governance and collaborate and monitor progress and increase accountability. As for specific population groups, children's SDH are of particular relevance. Different countries have taken steps to identify and generate interventions to address them. The need to focus on children and childhood is essential, given the growing scientific evidence on Health Development suggesting that early development years play an important role generating and maintaining socioeconomic inequalities in health in adulthood. In this sense, expert groups have stressed the importance of achieving inclusion from the beginning of life and during childhood and adolescence in a system that includes recognition of the rights of children and adolescents, recognition of the limits of the medical model to meet all their needs, primary care models that promote preventive actions, promoting models that focus on the child as part of a social, economic and political context, among others.7

2. Rights of the child as the basis for their welfare

The Convention on the Rights of the Child adopted in 19898 sets out the civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of children. It is guided by four principles: 1) the highest interest in the child, 2) right to life, survival and development, 3) right to express their opinions, which involves the citizenship of children and adolescents, and 4) the principle of nondiscrimination, which means that any denial or exclusion based on race, ethnicity, gender or nationality is unacceptable.

The Convention defines children as subjects of rights. Beyond that, they depend on their families. The Convention recognizes a number of rights on factors that are conceived as constituting child welfare, which in a state of poverty are absent. In this context, the best interest of the child principle requires consideration of the elimination of poverty in childhood and adolescence as a priority in the fight to reduce it through concrete actions implemented in the whole population.

These rights are integral and indivisible and drive a single legal, programmatic and policy framework in which each state, its institutions, community, families and individuals share the responsibility. The universal nature of these rights not only involves its application to all children, but also the monitoring of its implementation, especially in those groups with social disadvantages and, therefore, more difficult to exercise.

Every child has the right to be registered immediately after birth and have a name, a nationality and to preserve his/her identity and, if possible, the right to know and be cared for by their parents. States also accept the responsibility to protect children against discrimination. One of the basic principles of the Convention is the right to express their opinions. The document recognizes the right of children to express their views freely in all matters affecting them and insists that consideration will be given according to the age and maturity of the children.

The Convention recognizes the primary role of parents or guardians in the upbringing and development of children, but stresses the obligation of the State to support families through assistance, development of institutions, facilities and services for the care of children and all appropriate measures to ensure that children of working parents have the right to benefit from the eligible services and facilities. States parties are obliged to ensure the survival and development of children.

3. International perspective of Social Determinants of Health in child welfare

There are two approaches to define and measure the well-being of children. The first is considered as a multidimensional concept in which the dimensions are built by consensus, justified by the scientific literature about the research on children and as stated in the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child.8 The second approach is based on the assessment being conducted directly with children, measuring how they see or perceive their welfare. In practice, child welfare is generally regarded as a multidimensional concept due to the lower capacity of the youngest members of society to answer questions about their welfare.

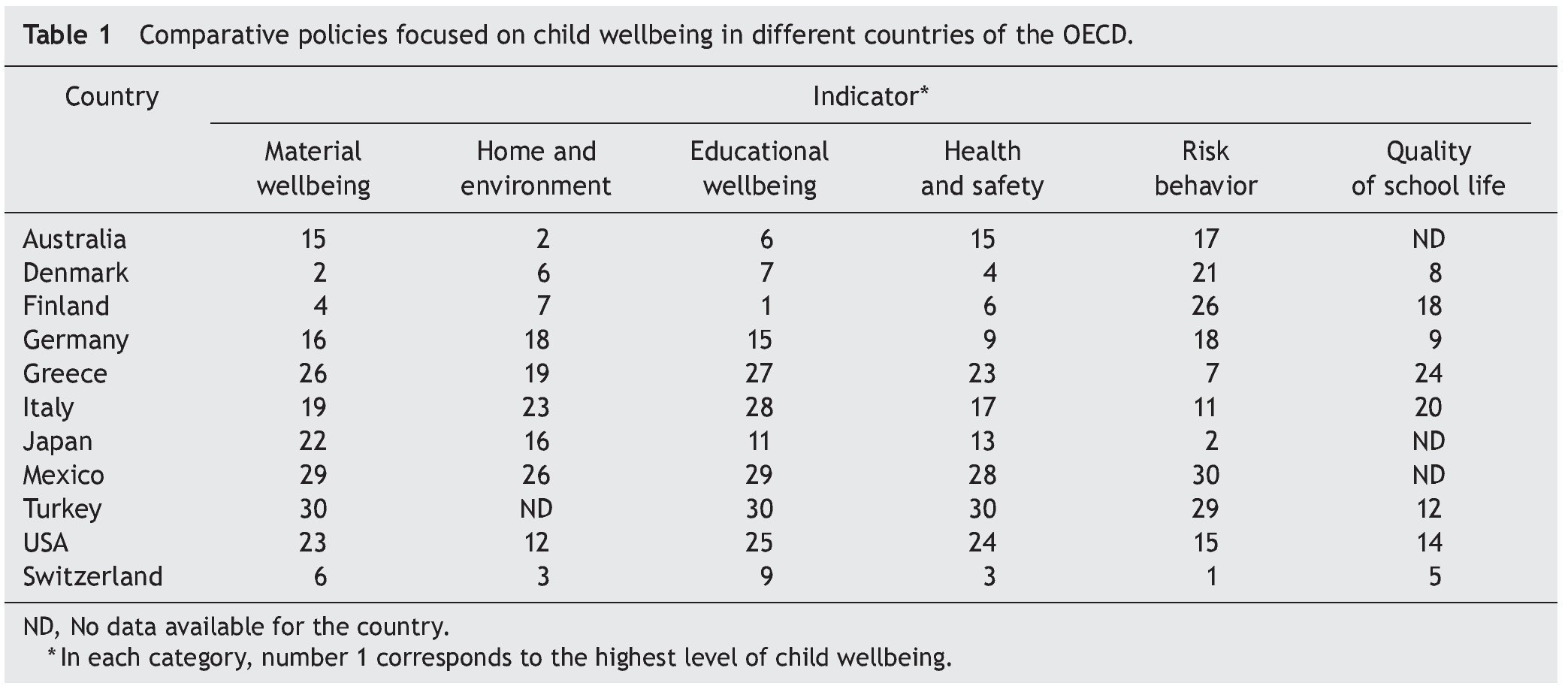

The methodology to assess the welfare of children developed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) considers six aspects comprising material welfare, housing and environment, education, health, risk behaviors and quality of education. At the same time, they are comprised of 21 indicators, which can be disaggregated by age, gender and migrant status.

No developed or underdeveloped country performs adequately in all aspects of child welfare. There are countries where there is gender or migrant status inequity.

The results of recent multidimensional analyses of children in OECD9 countries are summarized in Table 1. For example, child welfare for 11 of the 30 countries assessed in the six aspects above is shown. The values correspond to the place that the countries occupied in the rating of each aspect. The first places correspond to the highest welfare status. The analysis of the results allows countries to objectively identify their shortcomings so that they can introduce public policies for their improvement. It also identifies, in the leading countries, which are their best practices to extend to other countries, adapted to their own economic and social conditions.

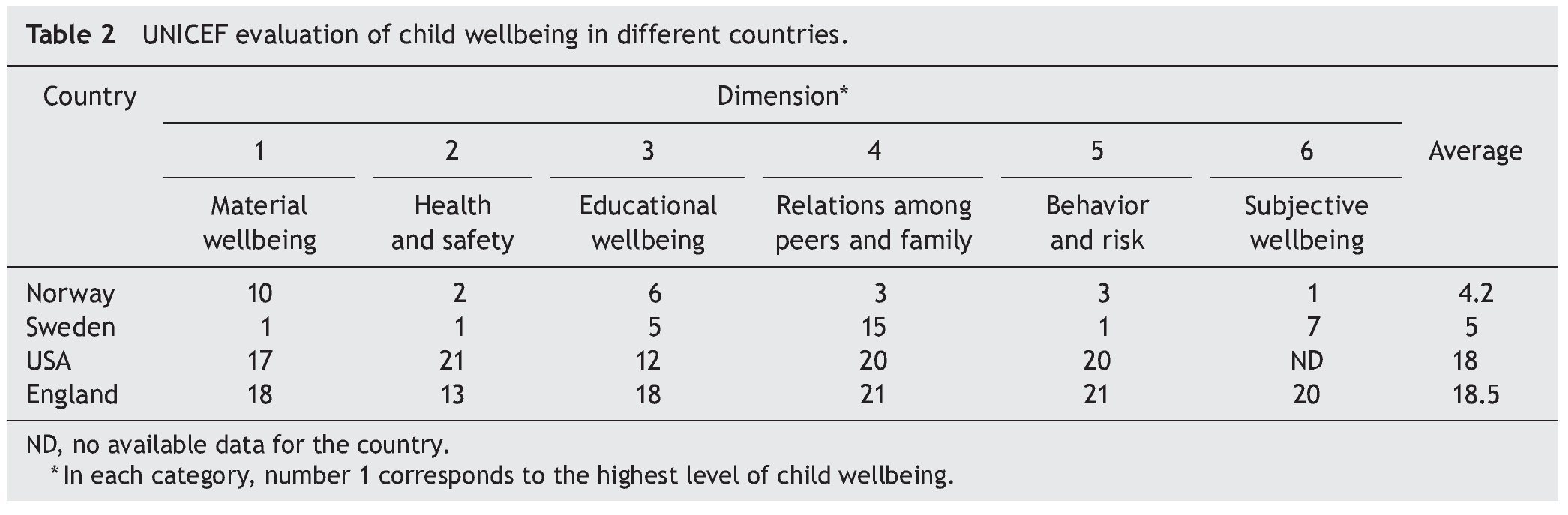

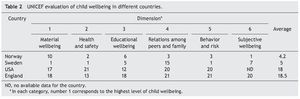

It is worth mentioning that there is another system of evaluation of child welfare developed by UNICEF,9 which has some differences with the OECD evaluation. Although it is based on the SDH, some reviews focused on three fundamental aspects.

1. Some elements analyzed do not accurately reflect the total welfare of children

2. Some indicators were taken at different times among countries, which does not reflect the same reality

3. Largely focused on assessing adolescents and not children at all stages

As an example of the UNICEF study, results from 4/21 countries tested (Table 2) are shown. It can be seen that Norway and Sweden were the countries with the highest level of welfare (lowest scores on the average of the six aspects as well as in each of them) compared with the United States and England, which within the context of the 21 countries evaluated were the lowest performing. This confirms that, even in the most developed countries, health inequalities and disadvantages of some population groups persist.

In 2000, world leaders gathered in New York to mark the start of the millennium and formed the International Foundation for Millennium Development Goals. These goals included, among others, universal access to education and the reduction of child mortality by 2015. At the same meeting, developed countries committed to support poor countries to achieve these objectives. In 2008, in order to assess the progress of the welfare of children, the program "Save the Children"10 developed the Child Wellbeing Index as a global tool for evaluating the performance of 141 countries on all continents on infant mortality, nutrition and access to primary education. The Year 2012 Report showed substantial progress in these indicators for 2011 compared to 2000. It was possible that more than two thirds of the children attend school, and the probability of a child dying before the first year decreased by one-third. Moreover, since 2000, underdeveloped countries achieved greater advances than developed countries, although the poorest countries, most of them sub-Saharan and those of Southeast Asia, had the lowest levels of welfare. However, not all news is good because malnutrition was one of the areas where there was no substantive progress (only 13%). In fact, it was identified that severe malnutrition increased in the second half of the decade (2000-2010); therefore, specific measures should have been considered.

4. Social Determinants of Health and welfare of children in urban world areas

In 2009, 21 urban agglomerations were scored as world megacities. This represents 9.4% of the world's urban population. In 1975, New York, Tokyo and Mexico City were the only megacities. Currently, 11 are in Asia, four in Latin America, two in Africa, two in Europe and two in North America. Eleven of these are the capitals of their countries.11

Rapidly and progressively, most children in any country, including Mexico, will grow in urban areas. It is estimated that by the middle of this century, more than two-thirds of the world's population (currently estimated at one billion persons) will live in urban areas. Children living in urban areas have better living conditions than their rural counterparts as a result of the highest standards of health, welfare, education and sanitation. However, progress has not been uniform in marginalized urban areas where children are daily subjected to great challenges and shortcomings, with very few guarantees to fulfill with the provisions of the Charter of Children's Rights.

When countries have detailed information of urban areas, wide disparities are found in survival rates, nutritional status, and access to health care or education for children living in informal urban settlements and impoverished neighborhoods. According to the UN with the information obtained of human settlements (UN-Habitat), it has been estimated that one in three urban inhabitants lives in slums with insecurity, overcrowding, unsanitary housing, pollution, traffic and crime, with a high cost of living, poor service coverage and competition for resources.

UN-Habitat defines a slum household as a group of individuals living under the same roof in an urban area and who lack one or more of the following: easy access to safe water in sufficient amounts at an affordable price, durable housing of a permanent nature that protects against extreme climate conditions, access to adequate sanitation in the form of a private or public toilet shared by a reasonable number of people, sufficient living space, which means not more than three people sharing the same room, security of tenure of land with documents that guarantee the protection against forced evictions, durability and safe housing.

Physical proximity to a type of service in large urban areas does not necessarily guarantee access. In fact, many urban inhabitants live near schools and hospitals but are unlikely to use these services. Poor people may lack the right and the necessary empowerment to request services from those institutions that are perceived as the domain of high economic status. Inadequate access to sanitation and drinking water places children at greater risk of disease, malnutrition and death. Studies have shown that, in many countries, children living in urban poverty have bad or worse conditions than those living in rural poverty in terms of weight for height or mortality in those <5 years old.11 The challenges are greater in countries with a low or medium level of development where the rapid growth of urban populations rarely is in accord with adequate growth in infrastructure and services. Children living in urban poverty are geographically close to the institutions responsible for the full range of civil, political, social, cultural and economic rights recognized by international human rights instruments. However, they do not often have access to them. Over a third of children in urban areas worldwide are not registered at birth, and in urban areas of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, only half are registered. The invisibility that derives from the lack of a birth certificate or an official identity increases the vulnerability of children to exploitation of all kinds, from recruitment by armed groups to be forced into early marriage or hazardous work. Obviously, the record itself is not a guarantee of access to services or protection from abuse. However, without a birth certificate, a child could be tried and punished by the court system as an adult or may be unable to access vital services and opportunities including education.

5. Social Determinants of Health in children in Latin America and the Caribbean

"A child is poor when he cannot exercise any of his rights, if only one."

In a recent study by the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC) and UNICEF, it was found that one of five children in this region is extremely poor, a scourge that affects more than 32 million children, and one out of three in extreme poverty is affected according to more than one of his/her fundamental rights. In rural areas, three of four children live in poverty, whereas in urban areas one of three children is reported in this situation. On the other hand, 2.3 million children are underweight for age and 8.8 million are affected by chronic malnutrition.12

Four of ten children in rural areas face hardships associated with inadequate housing conditions. The sanitation problem is more common in rural areas than access to drinking water: 9.4% of children (16.8 million) suffer serious hardships because they do not access to a sewage drainage system, resulting in pollution of their environment. Another 16.3% suffer moderate deprivation because the mechanisms for waste disposal are inadequate. Children with privations, severe or moderate, are just over 46 million in rural regions. Additionally, 22 million are either moderately or severely affected because they have poor access to drinking water. Regarding the hardships associated with housing conditions, 11.1 million children are severely affected and 32.1 million are moderately affected due to these inadequate conditions.12

Indigenous and Afro-descendent children present deprivation related to access to education and information.12 Breakthroughs in the region regarding the access to education affirm that the lowest proportion of children register deprivation: <1% have never attended school, although in absolute terms this represents 1.4 million children.

On the other hand, 5.6% of children in the region (10 million) have dropped out school with the risk of entering the labor market and sometimes experience forms of exploitation prohibited by Convention 182 of the International Labor Organization. This situation is particularly widespread in some Central American countries and Peru where >10% of children aged 6-17 years do not attend school. Unfortunately, in those places and in social groups where greater deprivation in education and child poverty are observed, access to media and communication is also poorer. For example, whereas in urban areas >97% of children correctly exercised their right to information, only 78% in rural areas do so.

According to the method used for the measurement of poverty,12 in 2008 10% of households in the region were classified as destitute, i.e., with insufficient income to cover the nutritional needs of their members, affecting about 14 million households.

By 2007, in Latin America there were ~84.5 million children in poor households (47% of the child population of the region) of which 18.7% belonged to households in extreme poverty. Ethnic conditions, geographic isolation, living in urban, suburban and rural areas and adult unemployment are important factors related to household welfare and, in particular, children's welfare.12 However, the heterogeneity of the children's reality greatly differs from country to country. In those with the highest child poverty (Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Peru), almost 41% of children were extremely poor. In countries with intermediate child poverty (Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay and Dominican Republic), extreme poverty affected a little less than 14% of children and in the countries with the lowest child poverty, only 8% of children were in that situation. Moreover, 53% of the extremely poor children were concentrated in Brazil (8.5 million), Mexico (4.3 million) and Peru (4.1 million).

6. Conditions of the Social Determinants of Health of children in Mexico

6.1. Urban and rural childhood populations

According to the National Population Census of 2010 implemented by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography, it was found that from a total of 39,226,744 children between 0 and 17 years of age, 10,428,007 (26.6%) lived in 171.993 rural areas (<2,500 inhabitants), mainly located in the states of Chiapas, Guerrero, Guanajuato, Mexico, Oaxaca, Puebla, San Luis Potosi and Veracruz and, of that total, 4,438,961 children lived in a household with at least one indigenous speaking family member. The eight states with the largest indigenous presence of children concentrated about 78% of the national total are Chiapas, Guerrero, Hidalgo, State of Mexico, Oaxaca, Puebla, Veracruz and Yucatan. The Third Periodic Report of Mexico based on Article 44 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child reported a great concern about the limited practice of rights of indigenous children in our country, especially migrant workers and in particular the limited access to education and health and the rate of infant mortality and maternal malnutrition. The high number of indigenous children who were working was also noted.13,14

6.2. Children with disabilities

The 2010 Census reported 567,095 children aged 0-17 years with a disability, representing 1.4% of the childhood population of Mexico. The prevalence of disability was 0.8% in children 0-4 years of age, 1.6% in the 5- to 9-year-old age groups, 1.8% in 10- to 14-year-old age group and 1.6% in the 15- to 17-year-old age group. At the national level, in 2006 the organization La Infancia Cuenta14 stated that although the national average of children between 6 and 14 years old who did not attend school was 8.7%, the average instrument for children with disabilities in that same age category quadrupled. In Oaxaca, for example, it reached about 47%. On the other hand, for the age group of 8-14 years, illiteracy reached 4.5%, and for children with disabilities it was almost ten times higher. In the state of Guerrero, it reached almost half of its children with disabilities. The most prevalent disability among children was a mental disability followed by motor, auditory, visual, and finally language disability. However, the latter has its greatest recurrence in the adolescent population compared to other age groups.

6.3. Single-parent families

The traditional two-parent family model has been losing ground in the past two decades, making way for single-parent families, blended families (where members have no relation) and single family households. The number of children has steadily declined since the 1970s, and female-headed households have increased. Changes in size, structure and organization, especially those linked to the incorporation of women into the workforce and increasing migration, among others, have impacted families in everyday life and in their sociocultural construction.13,14

6.4. Right to autonomy

In Mexico there are large gaps to ensure the right to autonomy of children. In 2004, 25.3% of children <1 year old were not registered, whereas in 2009 the percentage was 19.2%. The gap, although it has decreased, requires substantive progress in this regard.13

6.5. Health conditions

The infant mortality rate per 1000 live births has declined. In 2000 it was 16.8, whereas in 2006 it was 14.2. However, to be compared with developed countries, it is required to be decreased to at least 8/1000 live births.13

Coverage of complete vaccination for 1-year-old children in 2005 was 95.2%, which was maintained in 2010. These results can be considered very satisfactory even compared to those in developed countries.

Regarding the leading causes of morbidity in children, acute respiratory infections and diarrheal diseases persist, a situation that is accentuated in the states of Chiapas, Oaxaca, Puebla and Tabasco. It is not surprising then that almost one of four deaths of children <5 years old occur in Chiapas, one of five in the State of Mexico and about one of six in Puebla and Oaxaca, either by a diarrheal illness or respiratory infection, which could be avoided with appropriate care. The total number of malnourished children attended in 2009 was 3,444,828, of which 79.4% were classified as having mild malnutrition, 18.7% as moderate and 1.9% as severe. These results contrast with the high proportion of obese children in our country.

6.6. Adolescent health

Even though it is recognized that health inequities are universal, in the past decades specific SDH of certain population groups or specific health conditions have been studied such as maternal and adolescent mortality.14-16 It is considered essential to focus on the various age groups due to the growing evidence of health development, which suggests that in addition to the importance of acting in the early years of life it should be extended also to teenagers. It is then necessary to have comprehensive primary care models that promote preventive actions and models that focus on the child, viewing the child as a member of a social, economic and political context, among others.15

Like children in the first stages of their life, adolescents deserve special attention because of the diverse of factors influencing their full development. Several authors argue that, given Mexico's situation and the changes in the epidemiological, demographic and social profile, it is necessary to meet the health needs of adolescents from a holistic approach, with emphasis on the promotion of healthy lifestyles that promote a fair and equitable development and help focus the organized social response.

The General Management of Epidemiology of the Ministry of Health reported that, in 2010, the proportion of adolescents with high levels of marginalization was 17%, representing ~3.6 million. In education, enrollment continues to increase. In 2010, 78.5% of adolescents passed high school, 15.4% failed their grade and 6.1% dropped out of school. For high school, these figures estimate that 60% passed their grade, 31.7% failed and 8.3% dropped out.14

In 2010, the leading causes of death in adolescents were accidents, at a rate of 39.4/100,000 inhabitants in those from 10 to 19 years of age; assaults (homicides) at a rate of 11.6/100,000 and malignant tumors at a rate of 11.5/100,000. It is important to note that in 2009 of a total of 11,360 girls aged 10-14 years, the rate of having one living child was only one and, in adolescents aged 15-17 years, the rate was 204,547.13 Mortality data and teenage mothers make clear the need to strengthen self-care campaigns and reduce risky lifestyles. This is even more important because the country is changing from a population with a marked predominance of minors to one of adolescents.

6.7. Housing

Approximately 14.6 million children live in households without water, 13.4 million have no access to adequate sanitation, 1.1 million have no electricity, 5.2 million live in homes with a dirt floor, and 18.6 million in conditions where there is overcrowding.13 The right to drinking water is stated in the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which says that States Parties shall pursue the full application of available technology for the provision of adequate nutritious foods and drinking water. The percentage of the childhood population living in crowded housing increased from 42.6% in 2000 to 49.2% in 2005. The states with the highest percentage of children in insufficient living spaces are Chiapas, Guerrero and Oaxaca.

6.8. Education

There are several inequities that are largely influenced by social determinants. For example, in 2010 there were a total of 326.684 children aged 5-11 years who did not attend school. Regarding education in the period 2000/2001, the net rate was 50.5. This increased to 81.8 in the period from 2010 to 2011. Despite the increase, it should be noted that the quality of education is poor. This was observed in the high percentage of students in sixth grade with an underachievement result on the ENLACE test, which in 2006 was 84.2% for Spanish and 87.1% in mathematics. This deficiency decreased in 2011 to 60.27% and 67.93%, respectively. The same ENLACE test for students in the third year of middle schools in the same year showed an unsatisfactory result of 85.6% for Spanish and 96.6% in mathematics, whereas for 2011 was 96.6% and 88.4%, respectively. Finally, it is worth noting that, in 2010, 9.1% of the population (1,186,250 children 12-17 years old) neither worked nor studied.14

6.9. Child labor

Two of five children between 12 and 17 years of age are part of the economically active population (EAP) in our country. The highest rates of economic participation of children (>26%) are presented in Campeche, Chiapas, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Nayarit, Sinaloa and Zacatecas, whereas the lowest (<15%) are located in Baja California, Baja California Sur, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Mexico City and the State of Mexico.13

6.10. Protection laws in the states

In 2006, 22 states already had laws regarding the rights of children and adolescents; 82% of the 22 state laws that currently exist in the country clearly define that their purpose or "protected legal entity" is the protection of the rights of children. Also, all children are considered as full subjects of law. However, by 2006, 18% of states (Baja California, Morelos, Guerrero and Zacatecas) have not yet incorporated this concept into their legislation.13

Regarding the age criterion, the Convention on the Rights of the Child states that individuals up to 18 years old are considered as a child or adolescent. It is noteworthy that the legislation of Tamaulipas establishes the age of 16 as the age limit to be considered as a child. Another important element observed is the use of the term "minor" to refer to children in the laws prevailing in the states of Baja California, Guerrero and Morelos.

Mexico requires strengthening all actions in the shortest time possible, achieving results comparable to the standards of OECD countries. To achieve this, a steady, close and simultaneous collaboration is essential between the public sectors of the country, which can have an influence on the deficiencies of education, housing, safety, and health conditions of the localities, among others, with specific goals that achieve significant progress measured in 5-year periods.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest of any nature.

Received 13 December 2013;

accepted 21 January 2014

* Corresponding author.

E-mail:ljasso@himfg.edu.mx, jassogut@prodigy.net.mx (L. Jasso-Gutiérrez).