This study analyzes the effect that certain characteristics of board of directors in Spanish non-listed family firms have on performance. The results of a hierarchical regression analysis on a database of 544 firms show a negative effect of a higher proportion of executive directors and a positive effect of CEO duality. No effects were found in relation to the diversity of family directors (executive or non-executive). In relation to the effect of outside boards, the influence on performance is negative except when this variable was considered in interaction with CEO duality. In this case, the effect on performance was positive.

General literature on boards of directors includes numerous studies that attempt to identify the effect of certain variables related to the composition of the board of directors on company performance (for some recent contributions see Dalton and Dalton, 2011; Finegold et al., 2007; Kiel and Nicholson, 2007). However, few studies have dealt with boards of directors in family firms (Bettinelli, 2011; Uhlaner et al., 2007b). The review of the literature on boards and family firms shows that most empirical literature uses data of public family firms (e.g. Anderson and Reeb, 2004; Braun and Sharma, 2007; Chen and Hsu, 2009; García-Ramos and García-Olalla, 2011a,b; Lam and Lee, 2007; Leung et al., 2014; Prabowo and Simpson, 2011; San Martin-Reyna and Duran-Encalada, 2012) or uses combined samples of private and public family firms (e.g. Oswald et al., 2009). From the scant literature that focuses on boards in private family firms, some papers analyze the factors that determine a specific board composition (e.g. Bammens et al., 2008; Jaskiewicz and Klein, 2007; Voordeckers et al., 2007) and fewer studies specifically analyze the relationship between board composition and performance (e.g., Arosa et al., 2010; Maseda et al., 2014; Schulze et al., 2001; Westhead and Howorth, 2006). Appendix 1 presents an overview of the empirical studies on the relationship of board composition and performance in family firms.

Previous research has obtained mixed results when analyzing the link between board composition and performance, and this link is especially unclear in the case of private family firms (Maseda et al., 2014). However, boards can have a significant role in the performance of non-listed firms (Voordeckers et al., 2007), and could prevent failure in a significant number of them (Bammens et al., 2008). Therefore, it is important to study the function of boards in private family firms, so that the findings and recommendations of general studies on governance can be better defined and adapted to this specific type of organization (Bartholomeusz and Tanewski, 2006; Chen and Nowland, 2010; Chrisman et al., 2009; Uhlaner et al., 2007a).

The literature on boards of directors in family businesses highlight that the two main tasks of the board, as an internal administrative body, are the exercise of control and the provision of advice (Bammens et al., 2011) with agency and stewardship theories being the two main theoretical approaches (Bammens et al., 2011; Benavides-Velasco et al., 2011).

The exercise of control is based on the principles of the agency theory. From this point of view the aim of the board of directors is to mitigate the moral hazard problems specific to family firms. The sources of these problems are: the owning-family's pursuit of its own economic and/or non-economic interests thereby harming the interests of non-family stakeholders (mainly minority shareholders); the parents’ altruism and the associated problems of self-control; and the intra-family divergence of interests associated to the generational evolution of the firms (Bammens et al., 2011).

However, according to stewardship theory (Davis et al., 1997) decision-makers can show certain psychological and situational factors such as strong firm identification and involvement, and needs for personal and social fulfillment. These motivations can lead decision-makers to show pro-organization behavior and not the opportunistic behavior explained in the agency theory and, therefore, the main board's task is to support and advise the management instead of controlling them (Bammens et al., 2011).

On these bases, the aim of this study is to provide new evidence on the scarcely researched relationship between board composition and performance in non-listed family firms, focusing on the special features of these firms. Thus we argue that stewardship behavior and psychosocial altruism (as opposed to asymmetric altruism and the agency related problems of self-control) are more likely in non-listed family firms than in their listed counterparts. These special features are expected to have an influence on the tasks of the board in private family firms, and therefore on its composition.

Concretely, we analyzed the proportion of executive directors and CEO duality. These issues are usually addressed in general research on board composition but barely studied in family firms, especially in non-listed ones. This is a gap in the literature because there is evidence that the presence of executive directors and the existence of CEO duality are particularly high in private family firms. (Arosa et al., 2010; Cabrera-Suárez and Santana-Martín, 2004) and therefore it is important to analyze the consequences on performance of these special features. We also analyze the diversity of family directors (executive and non-executive). This variable is considered to be relevant when studying board composition in private family firms because it can be expected that the majority of directors in these firms are family members and that differences between them may derive in specific agency problems. The literature addressing the problem of intrafamily divergence of interest has suggested analyzing this aspect which has not been empirically studied yet. Moreover, we have addressed the issue of independence of the board in terms of the majority presence of outside directors, that is, non-executive and non-family directors. The variable related to board independence has received a great amount of attention in general literature on boards and it is the most addressed variable by the few articles focusing on boards in private family firms (see Appendix 1). Even though empirical evidence is not conclusive, it seems that recommendation on good governance tends to support the idea that outside boards are more efficient (García-Ramos and García-Olalla, 2011a). However, this may not be the case for family firms, and especially for non-listed ones (Arosa et al., 2010). The influence of outside boards on performance has been analyzed in this study both in general and also in interaction with CEO duality and with the diversity of family directors.

In order to reach these goals, a specific database has been created for this study which includes 544 private family firms. Among others, we have obtained data related to the composition of the boards distinguishing the different types of directors (executives versus non-executives, family versus non-family). As far as we know this is the first study including such kind of data about the boards in private family firms.

The study is structured as follows. Firstly, the theoretical framework begins with a discussion of the special nature of the private family firm. Then, the analysis of the consequences of these special features on the roles of the board and on its composition allows the hypotheses of the study to be proposed. Secondly, the methodology used to obtain and process the data and define the variables is outlined. After the results are presented, the final section presents the main conclusions drawn from the discussion of the results and establishes the limitations of the study, making suggestions for future research.

Theory and hypothesesThe private family firm: stewardship and psychosocial altruismOur line of argument, and consequently our hypotheses, is based on the premise that private family firms possess more defining characteristics of the essence of family firms than public family firms. Thus, private family firms correspond to what the literature considers typical family firms, with a concentrated shareholder base and family member insiders active in management and the board (Lane et al., 2006).

Privately held family businesses are often used as vehicles for sustaining the family's transgenerational economic and socio-emotional needs (Bammens et al., 2011; García-Ramos and García-Olalla, 2011b). Families are actively involved not only in ownership, but also in the management of the firm (Sciascia and Mazzola, 2008; Westhead and Howorth, 2006). Thus, family ties and relationships have a great influence in the functioning of the firm (Miller et al., 2007). On the contrary, listed firms will include non-family owners that will want to play an active role in the governance of the firms and in the decision-making process, probably wanting to impose economic and financial criteria over psychosocial criteria. Listed family firms are subjected to other pressures and conditioning factors over and above fulfilling the interests, aspirations and the approach of the family (Bammens et al., 2011; Combs, 2008; Dyer, 1986). Also, when numerous non-family members have ownership in the firm the intimacy and ease of communication that are often present in family firms may be damaged (O’Boyle et al., 2012).

Non-listed family firms are probably smaller than their listed counterparts, and this size difference is reflected both in the firm and the family. Smaller family firms could probably have stronger family ties that could aid in developing certain advantages in terms of social capital (Arregle et al., 2007; Hoffman et al., 2006; Pearson et al., 2008). A strong family social capital provides closure that ensures family members and other employees perform within established social norms (Danes et al., 2009; Hoffman et al., 2006). High-intensity ties and strong bonds between group (family) members can act to encourage reliability and transparency which enhance the capacity of the group to control member behavior and compliance with the group's norms (Björnberg and Nicholson, 2007; Calabrò and Mussolino, 2011; Long and Mathews, 2011; Salvato and Melin, 2008). Thus, strong bonds encourage family members to create conditions conducive to ethical behavior in the firm (Kidwell et al., 2012). Also, social capital can enable family firms easier access to valuable resources and capacities such as better customer service, long-standing relationship with other stakeholders, and a high level of goodwill (Kowalewski et al., 2010).

Thus, family members in smaller private family firms may have a higher propensity to display stewardship behaviors (Le Breton-Miller et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2008; O’Boyle et al., 2012). The main assumptions of stewardship theory (Davis et al., 1997) support the idea that executive behavior may be motivated by the general interests of a firm and not only by the private interests of executives. Thus, owner-managers of privately held family firms often use their firms as vehicles for sustaining the family's transgenerational economic and socio-emotional needs. However, in publicly traded family firms, where there is a higher distance between the family and the firm, the family incentive to exploit rather than nurture the business becomes stronger (Bammens et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2008).

Similarly, these elements associated to social capital and stewardship attitudes can also be linked to the concept of psychosocial altruism mentioned by Lubatkin et al. (2007). This type of altruism is based on the predisposition of parents to transmit their offspring a set of socially embedded values and norms to enable their psychological and social development. These values and norms are transferred through mimetic and normative forms of influence (socialization). This generates dynamics of reciprocity and interdependence which strengthen family bonds and improve communication between family members. These dynamics help transmit the firm's story, identity and language. This type of altruism encourages feelings of loyalty and trust between family members, facilitates communication and lengthens the decision-making time frame, all of which ultimately reduces agency costs (Bartholomeusz and Tanewski, 2006; Benavides-Velasco et al., 2011; Karra et al., 2006; Muñoz-Bullon and Sánchez-Bueno, 2012; Sciascia and Mazzola, 2008).

Private family firms tend to show stewardship behavior and psychosocial altruism. This could help explain why this type of family firm often relies on informal social controls (relational governance) rather than on contractual governance. Dynamics such as trust, shared vision and commitment to the firm play a fundamental role (Calabrò and Mussolino, 2011; Uhlaner et al., 2007a). These specific governance characteristics of private family firms are expected to influence board composition and management. In the following paragraphs we will develop the arguments based on a set of relevant variables and propose our hypotheses.

The role of executive directorsFrom a classical agency theory perspective, the presence of executive directors in the board could compromise the board's correct supervision of management teams. The management team (the agents) could make decisions to their own advantage rather than in the interests of company owners (the principals) (Fama and Jensen, 1983; Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Therefore, a greater presence of executives on the board could negatively affect this supervisory role and, ultimately, company performance.

However, the supervisory role of the board may not be the most important in private family firms where there is a strong presence of family members in management teams and board of directors (Cabrera-Suárez and Santana-Martín, 2004; Dyer, 1986; Lane et al., 2006; Lubatkin et al., 2005; Maseda et al., 2014). Thus there is a high level of correspondence between managers and company owners. This means that the classical agency problem related to divergence of interests between principal and agent loses relevance (Chrisman et al., 2004; García-Ramos and García-Olalla, 2011a).

On a similar vein, the problem of power abuse and extraction of private benefits at the expense of non-family minority shareholders, that is common in public family firms (Bammens et al., 2011; Kowalewski et al., 2010; Le Breton-Miller et al., 2011), may not affect private family firms, as the presence of non-family shareholders in these firms is unlikely (Cabrera-Suárez and Santana-Martín, 2004; Dyer, 1986; Lane et al., 2006; Lubatkin et al., 2005). In private family firms where family control is overwhelming there are more incentives to care for the business that is to be motivated by stewardship behavior, than to exploit their personal property (Kowalewski et al., 2010; Le Breton-Miller et al., 2011). Thus specific agency problems associated with self-control of family owner-managers are likely to be less important. Then, regarding the supervisory role, the presence of executive directors in the boards of private family firms does not have to cause any effects on performance.

However, the task of providing advice is especially relevant when relationships are based on stewardship attitudes. From this point of view the board's main task is to counsel stewards (executives) in their pro-organizational endeavors (Davis et al., 1997), complementing the knowledge of management teams (Bammens et al., 2011). In private family firms decisions on promotion toward managerial positions are likely to be based more on kinship criteria than on professional criteria related to capability and suitability for the position (de Kok et al., 2006). This is because family directors are considered a better option to preserve the values, culture and socioemotional wealth of the family firm (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). Executive directors have more in-depth, specific knowledge of the firm, but they may lack general business knowledge normally acquired at university and from previous experience outside the family firm (Bammens et al., 2011). Thus, private family firms can be especially vulnerable to deficits of expertise because they often have self-imposed personnel selection criterion that gives preferential or even exclusive consideration to family stakeholders (Chrisman et al., 2004). This can limit the strategic options considered by the board, as well as the depth and quality of contributions to the assessment and discussion of the firm's strategic alternatives (Bammens et al., 2008; Brunninge et al., 2007; Johannisson and Huse, 2000; Le Breton-Miller et al., 2011; Muñoz-Bullon and Sánchez-Bueno, 2012; Voordeckers et al., 2007). Therefore, the following hypothesis can be proposed:H1 In non-listed family firms, a higher proportion of executive directors on the board will negatively affect performance.

CEO duality occurs when the position of chief executive in a firm is held by the same person who serves as chair of the board of directors (Dalton et al., 1998). The literature includes controversy as to whether this circumstance has positive and/or negative consequences on decision making and company performance. In fact, this debate has been prevalent in literature on boards of directors for some time (Braun and Sharma, 2007).

The classical agency theory-based arguments state that having the chief executive holding the highest position of power on the board reduces the ability to supervise. Without appropriate monitoring, chief executives may abuse their power, put their own interests first and make decisions that are detrimental to the firm, such as hiring incompetent staff or making overly risky or conservative decisions and lead to strategic standstill (Combs et al., 2007; García-Ramos and García-Olalla, 2011b; Kor, 2006; Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2006).

However, in the case of private family firms, characteristics concerning the prevalence of stewardship attitudes and psychosocial altruism lead to the assumption that there will be fewer problems of power abuse and self-control. What is more, arguments in favor of CEO duality can be found. Thus, if the chief executive behaves as a steward, CEO satisfaction is tied to that of the other stakeholders in the firm, which means there is no risk of opportunistic behavior and the concentration of power and decision-making capacity in this person will be positive for the firm (Chen and Hsu, 2009). In this way, duality will be an advantage insofar as it would provide the firm with a clear focus and unity of command at the highest management levels, as well as greater autonomy and response capacity in top decision makers and improved flow of communication between the board of directors and the management team (Braun and Sharma, 2007; Palmon and Wald, 2002).

Similarly, high committed CEOs holding their positions during long periods of time may be more able to develop a series of specific advantages related to greater opportunities for learning and acquiring specific knowledge about their firms (Kowalewski et al., 2010; Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2006; Sacristán-Navarro and Gómez-Ansón, 2009). Therefore:H2 In non-listed family firms, having the same person serving as chair and chief executive (duality) will positively affect performance.

Over time, family firm structures are likely to evolve from controlling owner into sibling partnerships where varying proportions of ownerships are held by members of a single generation. They can also evolve into cousin consortiums where ownership is more fractionalized between members of third and later generations (Gersick et al., 1997). As a consequence vote control is going to be spread across different family members who normally occupy different roles (e.g. managers vs directors) and have different incentives and interest (Bammens et al., 2008; Gersick et al., 1997; Le Breton-Miller et al., 2011; Lubatkin et al., 2005; Thomas, 2009). This evolution in ownership is parallel to the development and growth of both the firm and the family, which in turn usually involves a weakening of family ties (Gersick et al., 1997; Neubauer and Lank, 1998).

We have already argued that the strength of family social capital is determined by the stability of the relationship between family members, the interaction and interdependence between them and the interconnections within the family. Thus, aspects such as trust, a sense of mutual obligation, norms of cooperation, and identification with the family group and the firm, which constitute the relational dimension of social capital, could weaken as family ties lessen (Salvato and Melin, 2008). Reduced family cohesion can make the firm more susceptible to experiencing destructive conflicts capable of dividing the family into factions based on generations or branches of the family, which detracts from performance (Björnberg and Nicholson, 2007; Kellermanns and Eddleston, 2007). Family rivalry and jealousy, in addition to decreased involvement of family members in company management, can be detrimental to communication and knowledge exchange (Zahra et al., 2007).

The weakening of family ties could have as a consequence that private family firms could lose their advantages in terms of social capital and could resemble listed family firms and even non-family firms. Consequently, from a stewardship theory perspective, the conditions for the alignment of objectives between family owners and family managers, that is, intrinsic motivations related to the welfare of the business, the importance of non-financial goals, emotion and sentiment-laden long term relational contracts (Chrisman et al., 2007), can be eroded. From an agency theory perspective this could lead to an increase in intrafamily divergence of interests produced by a change in the nature of the predominant altruism in family relations (Lubatkin et al., 2005). Psychosocial altruism could be replaced by asymmetric altruism with each family branch having its own set of economic and non-economic preferences and placing their own nuclear household's welfare ahead of the welfare of the extended family. This would consequently lead to an increase in agency problems and costs (Bammens et al., 2008, 2011; García-Ramos and García-Olalla, 2011b; Lubatkin et al., 2005). Therefore,H3 In non-listed family firms, a higher diversity of family directors will negatively affect performance.

In general literature on boards of directors, board effectiveness is argued to rely on its independence and this may be enhanced by including outsiders in it (Chen and Hsu, 2009). In general terms, outside directors are identified as board members who do not belong to the management team (Dalton et al., 1998). In the specific case of family firms, outside directors are regarded as those that do not belong to either the management team or the controlling family (Bettinelli, 2011; Brunninge et al., 2007; Fiegener et al., 2000; Jaskiewicz and Klein, 2007).

On the basis of the assumptions of agency theory, boards primarily consisting of outside directors have a greater incentive to fulfill the role of supervising and controlling the executive directors (including the CEO) so that their actions are aimed at satisfying owner interests and preventing opportunistic behavior. On this basis, most recent governance reforms are based on the premise that board of directors of publicly held corporations should work truly independently from management teams. In order to do so, boards of directors are recommended to be formed by a majority of outsiders (Fiegener et al., 2000; García-Ramos and García-Olalla, 2011b; Lane et al., 2006).

However, even for the context of public family firms the evidence on this issue is mixed. Anderson and Reeb (2004), for instance, in their study of public firms with founding family ownership, show that outside directors have a positive influence on performance by mitigating conflicts between shareholders groups and protecting the interests of minority investors through their supervisory role. On their part, García-Ramos and García-Olalla (2011b) found that independent boards improved firm performance for European family firms led by their founders and the opposite happens in firms led by descendants. San Martin-Reyna and Duran-Encalada (2012) and Klein et al. (2005) found a negative relationship between independence and performance of Mexican and Canadian public family firms respectively. The scarce evidence for the case of private family firms is also inconclusive. Thus, Schulze et al. (2001) found a negative relationship, Arosa et al. (2010) found a positive relationship but only for the case of firms in first generation, and Maseda et al. (2014) found and inverted U-shaped relationship also with differences between generations.

The literature seems to support the idea that for private family firms the contribution of outside directors in terms of the supervisory role may not be relevant, as the same individuals tend to be both owners and managers. Moreover, in the special context of these firms the influence of outside directors could even have negative consequences (Lane et al., 2006). Thus, insiders who are key stakeholders can be expected to care more than outsiders about the health of their firms (Le Breton-Miller et al., 2011). Also, outsiders will have less knowledge of the firm and its context, as they are not involved in the management teams and neither are they part of the owning families. A board with a predominance of outside directors can therefore suffer from a lack of specific knowledge and information about the firm (Bammens et al., 2008; Chen and Nowland, 2010; García-Ramos and García-Olalla, 2011a,b; Maseda et al., 2014). Furthermore, from a stewardship perspective, when outsiders are included in the boards with the intention of controlling managers, the intrinsic motivation of the managers may decrease, leading them to reduce their pro-organizational behavior and increase opportunism in those domains where they cannot be adequately controlled (Bammens et al., 2011).

Also, in relation to the concept of social capital, a board with a majority of outside directors is less likely to present the levels of trust and collaboration between board members, and subsequently with the management team, that boards dominated by family members may have. The flow of communication can also decline in comparison with a situation in which most or all of the directors belong to the group of insiders (the management team and/or the family) (Calabrò and Mussolino, 2011). Directors with low levels of internal social capital will be less known to the other directors, as well as less liked and trusted by them, which will lead to a decrease in levels of collaboration and communication exchange and the ability of the board to work as a team (Kim and Cannella, 2008). All of these can cause a decline in flexibility and adaptability in the decision-making process, as reaching consensus becomes more difficult (Brunninge et al., 2007; Ensley and Pearson, 2005). This can be detrimental to board effectiveness in terms of the advisor role and ultimately to company performance.H4 In non-listed family firms, a board with a majority of outside directors will negatively affect performance.

However, there can be situations where outside boards could be more beneficial to the firm. As stated above, CEO duality can be positive in terms of unity of command, greater autonomy, better communication flows with the management team and bigger learning opportunities. However, in private family firms, dependence on the chief executive as sole decision maker is usually very high (Calabrò and Mussolino, 2011; Feltham et al., 2005; Voordeckers et al., 2007). This can cause problems such as a lack of delegation and/or limited joint responsibility in decision making in favor of individuals with greater knowledge. It can also lead to difficulties in the process of succession, which can be detrimental to company development, and problems in adapting to changing circumstances in a competitive environment (Cutting and Kouzmin, 2000; Feltham et al., 2005; Harris and Helfat, 1998). In this context, outside directors can contribute important resources to the firm, such as general business knowledge, contacts and reputation, which can foster the advisory role of the board and improve the strategy development and implementation process (Bammens et al., 2011; Gabrielsson and Winlund, 2000; Fiegener et al., 2000; Maseda et al., 2014). Outside directors can play a very important role in the development of strategic change processes in private family firms by making additional, distinctive contributions to the strategic decision-making process (Bammens et al., 2008; Brunninge et al., 2007; Calabrò and Mussolino, 2011; Johannisson and Huse, 2000; Voordeckers et al., 2007). The following hypothesis can therefore be proposed:H5 In non-listed family firms, CEO duality will moderate the effect of an outside board on performance in a way that a board with a majority of outside directors will have a positive effect on performance when chief executive duality exists.

On the other hand, the distinction between executive and non-executive family directors, that is, the diversity of family directors, could lead to an increase in agency conflicts and a decrease in social capital as stated earlier. In these circumstances, outside directors can play a potentially beneficial role in terms of defending the interests of the various groups involved in the firm rather than only defending those of the top management team, or in terms of preventing or solving conflicts between interest groups (Arosa et al., 2010; Bammens et al., 2008, 2011; Voordeckers et al., 2007; Thomas, 2009). Outside directors can help to reduce information asymmetry among branches of the family and can serve as a mechanism to manage divergent point of view among family members bringing clear and objective counsel (Calabrò and Mussolino, 2011; García-Ramos and García-Olalla, 2011b). Also, the presence of outside board members can motivate family members to manage internal conflicts in a more constructive manner (Bettinelli, 2011). In this regard, Jaskiewicz and Klein (2007) conclude that in family firms in which alignment of objectives between family owners and family managers is low, the number of independent directors on the board is likely to be higher. The following hypothesis can therefore be proposed:H6 In non-listed family firms, the diversity of family directors will moderate the effect of an outside board on performance in a way that a board with a majority of outside directors will have a positive effect on performance when the diversity of family directors is higher.

The population of this study was Spanish non-listed family firms. In Spain family firms are a predominant form of business with a strong presence of the leading families in their ownership, boards and management teams (Cabrera-Suárez and Santana-Martín, 2004). Spain can be characterized as a country with a legal system based in the principles of the civil law in contrast with the Anglo-Saxon model based on common law. As a consequence, there is a low level of protection of external investors’ interest and boards of directors become very relevant as a mechanism of corporate governance (La Porta et al., 1998). Therefore, the Spanish context is quite suitable for this research given its particular characteristics.

In Spain there is no official database of non-listed family firms, so we have had to create it by indirectly identifying these firms from a general database provided by Informa Dun & Bradstreet. This company was asked to list all the firms on its database whose board of directors and/or management team included a minimum of two individuals with different first names who had the same two surnames in common. Because all individuals in Spain receive two surnames, one from each parent, people whose two surnames are identical are very likely to be siblings. Thus, the initial database comprised 4217 potential family firms. The information available on each of the companies identified can be grouped into two large categories: (a) general data of the company: name, mailing address, NACE code, sector of activity, date of incorporation, legal form and figures on company results, sales and number of employees for the years 1989–2007; and (2) first name and both surnames of members of the board of directors and the members of the management team. A further database was created which, in addition to the preceding variables, included a series of variables on the composition of the board and/or management team. These variables were created based on the above information, analyzing each firm one by one, and using secondary sources such as Internet when necessary to complete the data. These variables are:

- •

Existence or absence of a board of directors; board size or, in the absence of a board, existence of a sole administrator or joint administrators.

- •

Size of the management team and list of positions of responsibility.

- •

Number of siblings on the board of directors and/or in the management team, based on the presence of individuals with different first names whose two surnames were identical. These identical surnames were taken as a reference for identifying other family members involved in the companies.

- •

Number of family members on the board of directors and/or in the management team, based on the occurrence of individuals who had at least one of the surnames identified in common.

- •

Whether or not the chairperson of the board of directors was a member of the family.

- •

Presence and number of CEOs and general managers; whether or not they were members of the family; and correspondence of either of these positions with that of board chair.

- •

Number of executive directors, that is, those who simultaneously appeared as members of the management team, and whether or not they were members of the family.

- •

Number of outside directors, that is, non-family, non-executive directors. That is, those that had neither of the family surnames and were not members of the management team.

On completion of the database, firms in which any of the following circumstances occurred were deleted: (1) full general data were not available; (2) an insolvency administrator had been appointed; (3) the firm was a subsidiary company of another firm already included in the database; (4) the firm included two or more families that were not related in any way; and (5) the firm was chaired by a company. After this selection, the number of firms was 2179.

Lastly, to ensure that the characteristics of the companies would enable the objectives of the study to be achieved, firms in which the following conditions existed were selected:

- •

The chairperson of the board belonged to the family. This ensured that the companies studied were those in which family members held the highest positions of responsibility on the board.

- •

The board of directors had at least three members.

- •

The management team included at least three positions of responsibility.

- •

The number of employees was at least 10. The main reason for only selecting firms with more than 10 employees was to exclude micro-firms, as their organization and management needs are usually met by the management team. Thus, in firms with more than 10 employees, the board of directors is more likely to have a real role; their tasks are more complex, the organization has to be more sophisticated and there is a greater division of duties between the management team and the board of directors.

- •

The firm did not belong to the financial sector and was not listed on the stock market.

Consequently, we consider a firm to be a family firm if it has at least two people with different first names and two identical surnames (i.e. they are siblings) on the board of directors and/or management teams, and the chairperson of the board has at least one of these two surnames (i.e. he/she is a family member). That is how we tried to ensure that the identified firms are in essence family firms. On the one hand, these two criteria ensure there is a real family influence on decision making, which is an essential form of family involvement that shapes the distinctiveness of a family firm (Chua et al., 1999; Fiegener, 2010). On the other hand, the presence of siblings in the governing bodies implies an intention, or in fact, the transmission of leadership between generations in the family; this, in turn, is another key factor in the definition of family firms (Astrachan et al., 2002; Chua et al., 1999; Sirmon and Hitt, 2003; Zellweger et al., 2010). Finally, the presence of family members on the board and the fact that the chair of the board is a family member also allows us to infer that the ownership of the firm is in fact controlled by the family (García-Castro and Casasola, 2011). Previous studies on property and control structures of public family firms in Spain show that in more than two-thirds of the firms that have an individual or a family as ultimate owner, a member of the family holds the post of CEO or chairman of the board (Sacristán-Navarro and Gómez-Ansón, 2007). If this is the case in large listed firms, we can expect this to occur in non-listed family firms.

Thus, 544 firms were finally included in the study. The general characteristics of these firms are shown in Table 1. It can be seen that 28.8 percent of the firms were up to 20 years all, 36 percent of the firms were 21–30 years old, and 35.1 percent were more than 30 years old. More than 75 percent were corporations. Almost 50 percent carried out activities in the industrial sector, with the other 50 percent being involved in the sectors of building, trade and services. 62.7 percent had 50–150 employees and 28.4 percent had more than 150. 48.5 percent had a sales figure of 10–30 million euros in 2007 and 27.9 percent had a sales figure of more than 30 million in the same year. Most of the firms (79.2 percent) had a management team with three or four members.

Profile of the firms analyzed.

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 10 years or less | 48 | 8.8 |

| 11–20 years | 109 | 20.0 |

| 21–30 years | 196 | 36.0 |

| 31–40 years | 99 | 18.2 |

| 41–50 years | 51 | 9.4 |

| More than 50 years | 41 | 7.5 |

| Current legal form | ||

| S.A. (Corporation) | 411 | 75.6 |

| S.L. (Limited liability company) | 133 | 24.4 |

| Sector of activitya | ||

| Final demand products industry | 105 | 19.3 |

| Derived demand products industry | 148 | 27.2 |

| Building | 66 | 12.1 |

| Trade | 127 | 23.4 |

| Services | 98 | 18.0 |

| Number of employees in 2007 | ||

| 10–25 employees | 2 | 0.4 |

| 26–50 employees | 47 | 8.6 |

| 51–75 employees | 136 | 25.0 |

| 76–100 employees | 85 | 15.6 |

| 101–150 employees | 120 | 22.1 |

| 151–200 employees | 40 | 7.4 |

| 201–300 employees | 58 | 10.7 |

| More than 300 employees | 56 | 10.3 |

| 2007 sales figures | ||

| Less than 5,000,000 euros a year | 33 | 6.1 |

| 5,000,001–10,000,000 euros a year | 95 | 17.5 |

| 10,000,001–30,000,000 euros a year | 264 | 48.5 |

| 30,000,001–50,000,000 euros a year | 66 | 12.1 |

| 50,000,001–70,000,000 euros a year | 31 | 5.7 |

| 70,000,001–100,000,000 euros a year | 18 | 3.3 |

| 100,000,001–200,000,000 euros a year | 23 | 4.2 |

| More than 200,000,000 euros | 14 | 2.6 |

| Management team size | ||

| 3 or 4 members | 431 | 79.2 |

| 5 or 6 members | 99 | 18.2 |

| 7 or 8 members | 14 | 2.6 |

| Total | 544 | 100.00 |

The sector labeled as final demand products industry includes firms from the food industry; textile and footwear industry; wood, paper and cardboard industry; furniture industry and other industries related to jewellery, games, sport, music, etc. The sector labeled as derived demand products industry includes firms related to graphic arts, chemical industry, building material manufacture, machine building, electronic and electrical equipment industry, transport industry, and recycling, water and energy industries.

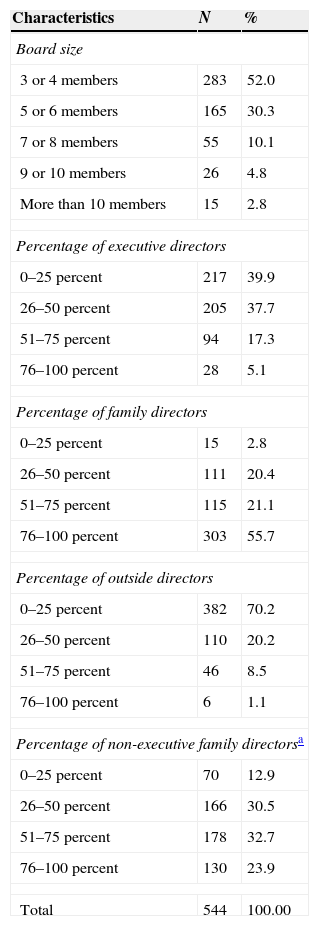

Table 2 shows the structure of the boards of directors in the firms studied. The data show that the size of most of the boards was three to six members (88.3 percent). In 77.6 percent of the firms the percentage of executive directors was lower than 50 percent. Most of the boards (76.8 percent) had a percentage of family directors higher than 50 percent. In 90.4 percent of the firms, the percentage of outside directors on the board was less than 50 percent. In 56.6 percent of the firms, the proportion of non-executive family directors to total family directors was more than 50 percent. The general conclusions that can be drawn from these results are that the boards of the firms analyzed were controlled by families and most included a high presence of non-executive family members.

Board structure in the firms analyzed.

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Board size | ||

| 3 or 4 members | 283 | 52.0 |

| 5 or 6 members | 165 | 30.3 |

| 7 or 8 members | 55 | 10.1 |

| 9 or 10 members | 26 | 4.8 |

| More than 10 members | 15 | 2.8 |

| Percentage of executive directors | ||

| 0–25 percent | 217 | 39.9 |

| 26–50 percent | 205 | 37.7 |

| 51–75 percent | 94 | 17.3 |

| 76–100 percent | 28 | 5.1 |

| Percentage of family directors | ||

| 0–25 percent | 15 | 2.8 |

| 26–50 percent | 111 | 20.4 |

| 51–75 percent | 115 | 21.1 |

| 76–100 percent | 303 | 55.7 |

| Percentage of outside directors | ||

| 0–25 percent | 382 | 70.2 |

| 26–50 percent | 110 | 20.2 |

| 51–75 percent | 46 | 8.5 |

| 76–100 percent | 6 | 1.1 |

| Percentage of non-executive family directorsa | ||

| 0–25 percent | 70 | 12.9 |

| 26–50 percent | 166 | 30.5 |

| 51–75 percent | 178 | 32.7 |

| 76–100 percent | 130 | 23.9 |

| Total | 544 | 100.00 |

Productivity measured as the natural logarithm of the ratio of sales to employees in 2007 was used as the outcome variable and, therefore, as the dependent variable. Productivity has been a well used variable as a measure of performance (e.g. Misterek et al., 1992; Sinclair and Zairi, 2000). Also the use of sales figures to calculate productivity is considered more trustworthy and less subject to manipulation than other figures related to profits (Oswald et al., 2009; Schulze et al., 2001). The logarithmic transformation was applied to make the variable behave according to a normal distribution (Kolmogorov–Smirnov Z=4.698, p=0.000 for the initial variable; Kolmogorov–Smirnov Z=1.267, p=0.081 for the transformed variable).

Independent variablesIn line with the hypotheses of this study, the following independent variables were established using the information entered into the database:

- •

CEO duality (DUAL). This is a dichotomous variable that takes the value “1” when the CEO or general manager also holds the position of board chair, and “0” otherwise. In the sample studied, 63.2 percent of firms showed duality.

- •

The proportion of executive directors (PEXECDIR) as the ratio of executive directors to total number of directors.

- •

The majority of outside directors on the board (MAJOUTDIR). This dichotomous variable takes the value “1” when the proportion of outside directors on the board is more than 50 percent and “0” when it is 50 percent or less. It has been considered that in a board with a majority of outside directors, these will have a considerable influence on the board, rather than a merely residual influence with no real power to make decisions. In fact, according to Schulze et al. (2001), experts in family firms recommend having a percentage of outside directors of 30–40 percent. In the present study this figure was raised to 50 percent, as the methods used to identify family members did not enable in-laws to be identified and therefore, some of the directors thought to be outside the controlling family may in fact not have fallen into this category. In the sample studied, 90.4 percent had a board on which outside directors were a minority.

- •

The diversity of family directors (DIVFAMDIR). This variable is measured as the absolute value of the difference in the percentages of executive and non-executive family directors. The mathematical expression is as follows:

Thus, the higher the value of the variable the lower is the diversity between family directors. That is, when there is a dominance of one type of family directors (less diversity) the value of the variable tends to 100. Conversely, in the case of maximum diversity (each type of family director holds the same percentage of seats at the board), the value of the variable is zero.

Moderator effectsA moderator or an interaction effect occurs when the moderator variable, a second independent variable, changes the relationship between another independent variable and the dependent variable, namely, an effect in which a third independent variable (the moderator variable) causes the relationship between a dependent/independent variable pair to change, depending on the value of the moderator variable. The moderator effect is represented in multiple regression by a compound variable formed by multiplying the independent variable by the moderator variable, which is entered into the regression equation. The two moderator effects proposed in hypotheses H5 and H6 are linked to two interaction variables whose purpose is to determine the extent to which the effect of a majority of outside directors on performance is positive in case of duality and/or a higher diversity of family directors. The two moderating variables therefore correspond to the following interactions of independent variables:

- •

Interaction between the DUAL variable and the MAJOUTDIR variable, labeled “DUAL*MAJOUTDIR”.

- •

Interaction between the DIVFAMDIR variable and the MAJOUTDIR variable, labeled “DIVFAMDIR*MAJOUTDIR”.

The following control variables were included in the multiple linear regression model:

- •

Sector of activity. Four dummy variables were established, with the reference value being the service sector. Thus the DUMSEC1 variable took the value “1” if the activities of the firm belonged to the industrial sector of final demand products, and “0” otherwise; the DUMSEC2 variable took the value “1” if the firm carried out its activity in the industrial sector of derived demand products, and “0” otherwise and so on. As a result, the regression coefficients of the four dummy variables represent the differential effect of each sector on the dependent variable in relation to the reference category (service sector).

- •

Age of the firm (LNAGE). Measured as the number of years since the firm's foundation. In this case, as with the dependent variable, the natural logarithm was applied to minimize asymmetry, given the high variability this variable presented.

- •

Size of the firm (LSIZE). Measured as the number of the employees in 2007. The natural logarithm was applied to minimize asymmetry, given the high variability of this variable.

We made use of a hierarchical multiple regression, which is a variant of the basic multiple regression procedure that allows specifying a fixed order of entry for variables in order to control for the effects of covariates or to test the effects of certain predictors independent of the influence of others. Thus, we were able to analyze: first, the effect of the control variables on the dependent variable; second, the joint effect of all independent variables on the dependent variable, regardless of the significance levels of the control variables; and, third, the additional effect of each of the moderating variables in the explanatory power of the model, because the change in R2 allows us to evaluate how much predictive power was added to the model by the addition of the moderator effect. If the change in R2 is statistically significant, then a significant moderator effect is present. Thus, only the incremental effect is assessed, not the individual variables. Finally, for the overall level of significance of the model the F ratio and the corrected R2 were used. We use the corrected R2 because in practice the use of R2 has some limitations when comparing models from the perspective of the goodness of fit.

ResultsBefore testing the hypotheses, the existence of multicollinearity between the variables in the model was tested, as this is one of the problems encountered in regression models, particularly in moderated regression analyses. To this end, three processes were used: analysis of correlation levels between the continuous variables, analysis of the values of the variance inflation factor (VIF), and analysis of tolerance levels.

Table 3 shows the correlation coefficients between the continuous variables used in the regression models. It can be seen that discriminant validity exists insofar as all correlation coefficients are low and therefore it can be assumed that there is no multicollinearity. The same conclusion can be drawn on observing the VIF values and tolerance levels, as the VIF values are far from the threshold of 10 and the tolerance levels are higher than 0.10.

Correlation coefficients between continuous variables in the model.

| Continuous variables | Mean | S.D. | LNSALEMPL07 | LNAGE | LSIZE | PEXECDIR | DIVFAMDIR | PNONEXECFADIR*MAJOUTDIR | DIVFMADIR*MAJOUTDIR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNSALEMPL07 | 12.035 | 0.822 | 1 | ||||||

| LNAGE | 3.196 | 0.603 | 0.099** | 1 | |||||

| LSIZE | 4.738 | 0.746 | −0.088** | 0.042 | 1 | ||||

| PEXECDIR | 36.827 | 25.194 | −0.024 | −0.130*** | −0.209*** | 1 | |||

| DIVFAMDIR | 36.672 | 28.019 | −0.038 | −0.055 | −0.001 | −0.012 | 1 | ||

| PNONEXECFADIR*MAJOUTDIR | 0.046 | 0.209 | 0.067 | −0.071 | 0.099** | −0.142*** | −0.198*** | 1 | |

| DIVFMADIR*MAJOUTDIR | 1.566 | 6.417 | −0.114*** | −0.007 | 0.104** | −0.235*** | −0.077* | 0.339*** | 1 |

The hypotheses were tested using hierarchical regression analysis, in which the variables are entered in successive blocks (Table 4). Thus Model I, which is the baseline model, includes only the control variables: sector of activity (DUMSEC1, DUMSEC2, DUMSEC3 and DUMSEC4), age of the firm (LNAGE) and size of the firm (LSIZE). Model II includes, in addition to the control variables, all the independent variables introduced in block, that is, the CEO duality (DUAL), the proportion of executive directors (PEXECDIR), the majority of outside directors on the board (MAJOUTDIR) and the diversity of family directors (DIVFAMDIR). Model III additionally includes an interaction term between the variables CEO duality (DUAL) and majority of outside directors on the board (MAJOUTDIR) – called “DUAL*MAJOUTDIR” – which allow recording the combined of the CEO duality and the majority of outside directors on the board on the ratio of sales to employees. Finally, Model IV added to the Model II the interaction term between the diversity of family directors (DIVFAMDIR) and the majority of outside directors (MAJOUTDIR) – called “DIVFAMDIR*MAJOUTDIR” – which allow recording the combined of both variables on the ratio of sales to employees. It should be noted that the moderating effect is significant if the change in the determination coefficient is significant. In this regard, empirical evidence indicates that an increase of more than 1 percent can be considered significant and therefore indicates the existence of a large moderating effect.

Results of multiple linear hierarchical regression models.

| Independent variables | Model I | Model II | Model III | Model IV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized beta coefficients | t | Standardized beta coefficients | t | Standardized beta coefficients | t | Standardized beta coefficients | t | |

| Constant | 38.258*** | 35.451*** | 35.781*** | 35.146*** | ||||

| DUMSEC1 | 0.325 | 5.784*** | 0.317 | 5.649*** | 0.292 | 5.153*** | 0.314 | 5.576*** |

| DUMSEC2 | 0.377 | 6.452*** | 0.363 | 6.237*** | 0.347 | 5.971*** | 0.364 | 6.264*** |

| DUMSEC3 | 0.329 | 6.290*** | 0.319 | 6.056*** | 0.310 | 5.901*** | 0.320 | 6.079*** |

| DUMSEC4 | 0.307 | 6.112*** | 0.304 | 6.045*** | 0.293 | 5.838*** | 0.302 | 6.009*** |

| LNAGE | 0.061 | 1.360 | 0.041 | 0.914 | 0.057 | 1.276 | 0.046 | 1.032 |

| LNSIZE | −0.052 | −1.162 | −0.064 | −1.416 | −0.076 | −1.690* | −0.062 | −1.366 |

| DUAL | 0.142 | 2.942*** | 0.101 | 2.003** | 0.139 | 2.866*** | ||

| PEXECDIR | −0.146 | −2.865*** | −0.138 | −2.721*** | −0.143 | −2.803*** | ||

| MAJOUTDIR | −0.088 | −1.857* | −0.204 | −3.183*** | −0.023 | −0.324 | ||

| DIVFAMDIR | −0.054 | −1.162 | −0.055 | −1.190 | −0.045 | −0.954 | ||

| DUAL*MAJOUTDIR | 0.170 | 2.666*** | ||||||

| DIVFAMDIR*MAJOUTDIR | −0.085 | −1.293 | ||||||

| Corrected R2 | 0.129 | 0.150 | 0.162 | 0.172 | ||||

| F | 12.312*** | 9.126*** | 9.055*** | 8.460*** | ||||

| ΔR2 | 0.029 | 0.013 | 0.003 | |||||

| ΔF | 3.878*** | 7.106*** | 1.672 | |||||

The results of the first regression model, shown in the second column of Table 4 (Model I), indicate that the sector of activity in which the firm is involved is a variable that influences company performance. Concretely, it is shown that the ratio of sales to employees is higher for the firms in no service industries as could be expected. However, the age of the firm and its size do not have influence on productivity.

The next step was to estimate the regression model by adding the results of the four explanatory variables considered in this study (shown in column three of Table 4 – Model II). It can be seen that a significant change occurred in the determination coefficient (ΔR2=2.9 percent; ΔF=3.878; p=0.004) in this model, indicating the significant effect of the explanatory variables considered on the dependent variable and therefore the effect of board of director structure on company performance. More specifically, the results of this regression analysis enabled the following conclusions:

- •

A negative relation exists between the proportion of executive directors on the board and non-listed family firm performance (t=−2.865, p=0.004), which means that hypothesis H1 is accepted, since it was expected that a higher proportion of executive directors would have a negative effect on the performance of the firms.

- •

The positive and significant coefficient for the DUAL variable indicates that having the same person holding the positions of board chair and chief executive is positively related to performance (t=2.942, p=0.003), which means that hypothesis H2 is accepted.

- •

A higher diversity of family directors does not have a significant effect on non-listed family firm performance (t=−1.162, p=0.246). Also the negative sign of the coefficient is not the expected one because it means that the higher the value of this variable (less diversity) the worse the effects on performance. Therefore hypothesis H3 is rejected.

- •

A majority presence of outside directors on family firm boards has a significant negative effect on family firm performance (t=−1.857, p=0.064), which means that hypothesis H4 is accepted.

An estimation was made of Models III and IV, which incorporate to Model II the two moderating effects considered independently. Results of these models are also shown in Table 4. As seen in the results obtained, the incorporation of the first moderating variable (DUAL*MAJOUTDIR) into Model II significantly increased the determination coefficient (ΔR2=1.3 percent; ΔF=7.106; p=0.008). Because of this, the effect of this variable is significant (t=2.666, p=0.008). This implies that a majority of outside directors on non-listed family firm boards has a positive effect on performance when CEO duality exists, so hypothesis H5 is accepted. Thus, if there is CEO duality, the positive effect of this variable on performance is stronger because CEO duality has a positive moderator effect on the relationship between the majority of outside directors and performance. The standardized beta coefficient (0.170) shows the unitary change in the effect of CEO duality on performance when the proportion of outside directors changes. Thus, if this proportion is more than 50 percent, the total effect of CEO duality on performance is 0.271 (0.101+0.170); but when it is lower or equal to 50 percent the effect is 0.101.

In relation to the second moderating variable (DIVFAMDIR*MAJOUTDIR), its effect is not significant (t=−1.293, p=0.197). In fact, the incorporation of this second moderating variable into Model II does not significantly increase the determination coefficient (ΔR2=0.3 percent; ΔF=1.672; p=0.197). Therefore, H6 must be rejected.

Lastly, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov Z-test was applied to the non-standardized residuals of Models III and IV to test the normality of the residuals and guarantee the reliability and validity of the results. The results obtained showed the normality of the residuals (Kolmogorov–Smirnov Z=1.324, p=0.060 for Model III and Kolmogorov–Smirnov Z=1.378, p=0.045 for Model IV).

To validate the model, a robustness check was carried out using an industry-adjusted regression analysis, where the natural logarithm of firm productivity relativized in terms of the productivity of the firm's economic sector was used as the dependent variable (Appendix 2). The results can be considered robust as there were no significant differences when it came to verifying the hypotheses. There is also no significant difference in the standardized coefficients.

Discussion and conclusionsThis study contributes empirical evidence to the little-studied area of governance in family firms, with particular emphasis on non-listed family firms. The special features of these firms in terms of stronger family ties, steward-like attitudes and of psychosocial altruism give special relevance to the advisor role of the board. Therefore, we have included complementary theoretical approaches to agency theory, such as the stewardship theory, to explain board composition and its influence on performance, due to the specific features of decision making and governance dynamics conferred on these firms by their family aspect. Therefore, we believe that this paper contributes significantly to the literature on family firms. Published research on family firm governance uses samples mainly from listed firms, and their theoretical line of argument is often based on the traditional literature on family firms, which really refers to the nature and behavior of private family firms (Combs, 2008). This paper starts from this premise and argues hypotheses on board composition and performance which are somewhat different to the ones proposed in the general literature on governance and which take into account the specific nature of private family firms. The overall conclusion that can be drawn from the results obtained is that the structure of the board of directors affects the performance of non-listed family firms, and that the suitable structure is somewhat different to the one suggested in the general literature on boards or in the literature on boards in public family firms.

According to our findings, a higher proportion of executive directors negatively affects performance, just as we expected. Although the typical agency problems associated to asymmetric altruism and opportunistic behavior are less common in private family firms, a board with a high presence of executives allows little room for alternative points of view from those of the management team. This can limit the strategic options considered by the board, as well as the depth and quality of contributions to the assessment and discussion of strategic alternatives, negatively affecting the advisor role of the board. This problem of a lack of quality in decision-making processes can be accentuated if, as usually happens, decisions on promotion toward managerial positions in private family firms are based more on kinship criteria than on professional criteria related to capability and suitability for the position (de Kok et al., 2006). Thus, an interesting line for future research could explore the relationship between governance and the management of human resources in family firms.

As expected, the results also show that having the same person holding the top position of responsibility both on the board and in the management team has a positive effect on family firm performance. These results differ from those obtained by Braun and Sharma (2007) for family-controlled public firms. These authors state that duality by itself does not influence firm performance and that the relationship between duality and performance is moderated by the level of family ownership. They conclude that non-duality is more effectual in relation to performance when the family has a lower level of ownership, because in that situation noncontrolling (i.e. nonfamily) stakeholders are more able to mitigate expropriation from the part of the family. Therefore, Braun and Sharma (2007) found support for the arguments of agency theory in the case of the public family firm. On their part, Lam and Lee (2007), also studying public firms, found a negative relationship between CEO duality and performance. They explained this result based on agency theoretical arguments related to managerial entrenchment and expropriation of minority stakeholders. However, García-Ramos and García-Olalla (2011b) found that the relationship between CEO duality and firm performance is positive for family firms run by descendants and non-significant for family firms led by founders. The authors suggest that these results are consistent with the position of stewardship theorists who argue that CEO duality can have a positive influence on performance. This may be especially true for the context of private family firms, where high levels of family ownership could enhance the level of commitment of family leaders and therefore their motivation toward stewardship behavior (Le Breton-Miller et al., 2011). As a result, duality could be a way of providing firms with the advantages derived from the unity of command at top management levels, such as a clearer strategic orientation, greater autonomy and greater response capacity. Also, in private family firms, family leaders tend to hold their positions for a long period of time, which can be advantageous in terms of learning and acquiring specific knowledge of their firms (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2006).

No evidence was found to support the hypothesis proposed in this study that a higher diversity of family directors negatively affects company performance. The distinction between executive and non-executive family directors may not necessarily imply an increase in the divergence of interests or, therefore, of agency conflicts between the two types of directors. Similarly, the family ties and the associated advantages in terms of social capital may not necessarily be adversely affected by a differentiation between family directors. That depends, among other things, on the capacity of the families to govern themselves and to keep unity between family members using specific family governance mechanisms like family protocols or family councils (Lubatkin et al., 2005; Neubauer and Lank, 1998). Therefore, to be able to test these possible explanations, it would have been useful to have data on the distribution of ownership among family members, the type of economic and non-economic objectives pursued by the owners, the degree of congruity between the objectives of individual groups of relatives, the quality of family relationships and the existence of governance mechanisms within the family. These variables were not available due to the sources of information used, although these issues would constitute interesting areas for future research.

As expected, we found a negative relation between the existence of outside boards and performance. This result seems to support the idea that, in non-listed family firms, the benefits of an outside board in terms of a higher supervisory capacity and a wider base of resources could be offset by the losses in terms of specific knowledge about the firm, level of commitment, emotional ties, trust, and other benefits related to social capital that insiders are more likely to posses.

However, the results also show that the influence of outside boards becomes positive when it is considered in interaction with CEO duality. That is, outside directors play a significant positive role in situations where maximum power is held by the chief executive. Given that the occurrence of CEO duality is higher in first generation family firms (Cabrera-Suárez and Santana-Martín, 2004) these results are somehow congruent with those obtained by García-Ramos and García-Olalla (2011b) for public family firms and by Arosa et al. (2010) and Maseda et al. (2014) also in the context of Spanish non-listed family firms. García-Ramos and García-Olalla (2011b) and Arosa et al. (2010) found that outside directors have a positive effect on the performance of family firms but only for those in the first generation. On their part, Maseda et al. (2014) found a non-linear inverted U-shaped relationship between the proportion of outsiders and performance, with the optimal proportion being higher for first generation firms than for second generation ones. It seems that when there is a powerful family Chair/CEO, outside directors are not perceived as a threat and their contribution may be perceived to be positive in terms of knowledge, experience and contacts, which could complement the benefits provided by the chief executive and the rest of the management team. Specifically, earlier studies in closely held firms suggest that outside directors could have an important role in improving strategic decision making and achieving strategic change (e.g. Bammens et al., 2008; Brunninge et al., 2007; Johannisson and Huse, 2000; Voordeckers et al., 2007). These change processes, and specifically succession, can be particularly difficult for the family firms in first generation due to their lack of experience, and this can give a higher value to the advice provide by the outside directors (Calabrò and Mussolino, 2011; Fiegener et al., 2000).

Finally, even though the evidence obtained does not reach significance, the results suggest that the influence of outside boards could turn positive when the diversity of family directors grows. It seems that outside directors could play a role of balancing the interests of diverse family members and preventing specific agency problems related to the evolution of business families. Thus, we could agree with authors such as Bammens et al. (2008) and Uhlaner et al. (2007a), who state that the nature of the board's role in privately held firms may change over their life-cycle. This could also be an interesting point for future research.

As a general conclusion, the recommendations on “good governance” usually found in the general literature on corporate governance need to be better clarified in the case of non-listed family firms, as suggested earlier (e.g. García-Ramos and García-Olalla, 2011a; Lam and Lee, 2007; Lane et al., 2006; Uhlaner et al., 2007a). This, in turn, has relevant practical implications for the decisions on board composition in this type of firms. One important point is that boards of directors in private family firms may present a strong family influence without damaging performance. This family influence may be exerted through a majority of family directors (different from the members of the management team) or through a family chairman also occupying the position of CEO. However, the combination of the two circumstances (majority of family directors and family CEO duality) seems not to be an optimal situation. It may create a decision making context characterized by too much endogamy and uniformity of criteria that could hinder performance. Therefore, when there is duality, a board with a majority of outside directors would be preferable. That is, family commitment, unity of command and idiosyncratic knowledge of the business should be combined with external advice and a wider range of points of view. However, given the importance of certain factors such as trust for the functioning of private family firms, it may be advisable that these outside directors should belong to the category of affiliates, as suggested in previous studies on private family firms (e.g. Arosa et al., 2010). Affiliate board members are outside directors with business or social ties to family firms actors (for example, consultants or advisers). These ties allow them to develop trust bonds with members of the owning family that will make them more effective in performing the advisory task (Bammens et al., 2011; Jones et al., 2008).

The present study has limitations that must be taken into account when evaluating the conclusions drawn. On the one hand, no data were available on the ownership of the firms, which is a significant governance variable. However, it must be noted that the study focuses on non-listed firms, in which owners who are not part of the families controlling company management are infrequent and the ownership structures are very concentrated (Cabrera-Suárez and Santana-Martín, 2004; Lane et al., 2006). In this situation, the variable of interest could be the distribution of ownership inside the family. Thus, future research could aim to obtain data on this issue.

The criteria used to identify family firms (mainly presence of siblings in the boards or in the management teams and family chairman) imply that the study is limited to a specific type of family firm. It has been argued that this type could be the one that better represent the typical family firm. However, future research could aim to deepen in the identification and analysis of different categories of private family firms, and the effects of these differences on the composition and functioning of the board and other governance mechanisms.

The cross-sectional nature of the data meant that temporal delay between the independent and dependent variables could not be included. However, findings on Spanish listed family firms show that board structure is quite stable (García-Ramos and García-Olalla, 2011a). It can therefore be assumed that this stability is even greater in the case of non-listed family firms. In any case, future studies could focus on obtaining more complete databases that include data panels over several years, or on conducting in-depth studies that allow the relevant variables to be studied longitudinally (Benavides-Velasco et al., 2011). Also, due to the limitations in our database we could not prove the robustness of our results using other measures of performance (e.g. ROA) as would be desirable (O’Boyle et al., 2012). In fact, future research should try to include multiple performance measures, particularly some that accounted for non-economic goals, as suggested by Chrisman et al. (2004).

Similarly, with the data available we could not distinguish between outside directors who could be considered totally independent and those that are known as affiliate directors. Thus, the directors we have defined as outsiders do not belong to the board of management team or the family, but that does not mean they are independent. These directors could have some type of professional or social link with family members and/or the firm. Future lines of investigation could make that distinction and clarify if outside directors in private family firms should be totally independent or if a certain degree of affiliation is advisable to improve trust and collaboration between family members, as has been suggested in the literature (Bammens et al., 2011).

Lastly, the influence of boards of directors on company performance cannot be understood only in terms of board composition. Aspects associated with the dynamics that occur within a board must also be taken into account (Huse, 2000). In this sense, a behavioral approach should be adopted in the study of boards that focuses on decision-making processes and the problems of coordination, exploration and knowledge management (van Ees et al., 2009). In this respect, future research adopting methodologies that allow in-depth analysis of these dynamics would be advisable. In studies of this type, the theoretical framework related to the concept of familiness, particularly in terms of its association with the concept of social capital, could be particularly relevant.

Overview of the empirical studies on the relationship of board composition and performance in family firms.

| Reference | Type of family firms | Independent variable in relation to board composition | Relationship with performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson and Reeb (2004) | Public | Fraction of independent directorsRatio of inside (family) directors to independent directorsFraction of affiliate directors | Positive for the fraction of independent directorsInverted U-shaped for the ratio of family directors to independent directorsNegative for affiliate directors |

| Arosa et al. (2010) | Private | Fraction of outside directors (affiliate and independent) | Positive for the fraction of affiliate directorsPositive for the fraction of independent directors but only for firms in first generation |

| Braun and Sharma (2007) | Public | CEO duality | Relationship moderated by the level of family ownership |

| García-Ramos and García-Olalla (2011a) | Public | Proportion of independent directorsInternal ownership | Negative for the proportion of independent directorsInverted U-shaped for internal ownership |

| García-Ramos and García-Olalla (2011b) | Public | Proportion of independent directors | Positive for firms run by their foundersNegative for firms run by descendants |

| CEO duality | No effect for firms run by their foundersPositive for firms run by descendants | ||

| Klein et al. (2005) | Public | Index of board composition (independence) | Negative |

| Lam and Lee (2007) | Public | CEO duality | Negative |

| Leung et al. (2014) | Public | Board independence | Non-significant |

| Maseda et al. (2014) | Private | Proportion of outsiders | Inverted U-shaped |

| Prabowo and Simpson (2011) | Public | Fraction of independent directors | Non-significant |

| San Martin-Reyna and Duran-Encalada (2012) | Public | Number of independent directors, shareholder directors and affiliate directors | Negative for independent directorsPositive for shareholder and affiliate directors |

| Schulze et al. (2001) | Private | Percentage of outside directors | Negative |

| Villalonga and Amit (2006) | Public | Proportion of independent directors | Non-significant |

| Westhead and Howorth (2006) | Private | Proportion of family directors | Non-significant |

| Yeh and Woidtke (2005) | Public | Board affiliation | Negative |

Robustness check: results of multiple linear hierarchical regression models.

| Independent variables | Model I | Model II | Model III | Model IV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized beta coefficients | t | Standardized beta coefficients | t | Standardized beta coefficients | t | Standardized beta coefficients | t | |

| Constant | −0.904 | −0.021 | 0.064 | −0.158 | ||||

| LNAGE | 0.074 | 1.595 | 0.051 | 1.103 | 0.066 | 1.417 | 0.057 | 1.217 |

| LNSIZE | −0.066 | −1.408 | −0.076 | −1.608 | −0.087 | −1.846* | −0.073 | −1.554 |

| DUAL | 0.159 | 3.095*** | 0.110 | 2.054** | 0.155 | 3.011*** | ||

| PEXECDIR | −0.156 | −2.887*** | −0.147 | −2.742*** | −0.153 | −2.831*** | ||

| MAJOUTDIR | −0.103 | −2.061** | −0.232 | −3.437*** | −0.034 | −0.457 | ||

| DIVFAMDIR | −0.050 | −1.026 | −0.054 | −1.111 | −0.041 | −0.828 | ||

| DUAL*MAJOUTDIR | 0.189 | 2.820*** | ||||||

| DIVFAMDIR*MAJOUTDIR | −0.090 | −1.299 | ||||||

| Corrected R2 | 0.005 | 0.031 | 0.046 | 0.033 | ||||

| F | 2.180 | 3.472*** | 4.158*** | 3.222*** | ||||

| ΔR2 | 0.034 | 0.016 | 0.004 | |||||

| ΔF | 4.089*** | 7.950*** | 1.688 | |||||