The goal of this study is to analyze the incidence of dominant owners in the probability of the presence of political directors and the effect of said presence on firm value. The study uses a sample of non-financial Spanish companies listed on the Spanish Stock Exchange over the period 2003–2012. The results show that around half of the firms have at least one ex-politician on their board of directors. Furthermore, the results indicate that dominant shareholders’ voting rights and family nature have a negative effect on the likelihood of having ex-politicians on the board of directors. Moreover, the results show that the presence of political connections positively affects firm value. Further analyses show that this relationship is dependent upon the nature of the dominant owner, the use of pyramidal structures, the tenure of board members and the political directors’ ownership stake.

Spain, like most countries in Continental Europe, is in the process of changing its corporate governance system. In this context, institutions, academics, politicians and firms highlight the need to improve corporate governance in order to limit potential conflicts between internal agents as dominant owners and managers and minority shareholders. At the same time, the economic, financial and institutional crises affecting Europe since mid-2007, particularly in countries such as Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Spain, has led to an increased interest in the study of political and business ties and their effect on firm behaviour. The Spanish business environment is characterized by a high level of corruption. According to the Corruption Perceptions Index 2013 (Transparency International), Spain and Italy are two of the largest European countries with the highest levels of corruption. Moreover, according to the Global Competitiveness Report 2013–2014 (World Economic Forum), out of the 148 countries surveyed, Spain ranks 101st in terms of citizen trust in politicians, 93rd in terms of board of directors effectiveness and 138th in terms of ease of access to bank loans.

The low transparency associated with the links between corporate and political elites, as well as the absence of previous empirical evidence on the presence of political connections in the Spanish context, shows that the level of knowledge about this phenomenon does not exceed the level of anecdotal evidence and the number of cases with significant media coverage, such as the appointment of ex-Spanish president Don Felipe González Márquez as director of Gas natural, S.A. in 2010 or the hiring of the ex-Spanish president Don José María Aznar López as an external consultant for Endesa in 2011.

The studies focusing on political connections face two important challenges. First, the links between corporate and political elites are often characterized by their opacity to facilitate political rent-seeking, especially those rents of dubious legality (Leuz and Oberholzer-Gee, 2006). Thus, the connections between politicians and entrepreneurs can be made using private channels that remove the company from the scrutiny faced by politically connected firms (e.g., Riahi-Belkaoui, 2004; Chaney et al., 2011; Boubakri et al., 2012). Second, the analysis of explicit political connections in a firm faces the difficulty arising from the absence of a generally accepted definition of political connection. This makes it difficult to empirically study the relationship between political ties and corporate behaviour (Chen et al., 2011). A firm's political ties can be the result of politicians moving from the political arena to the business environment (revolving door) or vice versa (reverse revolving door). In this paper, we focus on revolving door cases. More specifically, following earlier literature (e.g., Faccio, 2006; Goldman et al., 2009; Chaney et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2011; Boubakri et al., 2012; Duchin and Sosyura, 2012), we consider the presence of politicians on a firm's board of directors as a proxy for the existence of political connections.

Previous studies have found several motivations for the existence of politically connected firms. Thus, Khwaja and Mian (2005) argue that politically connected firms enjoy increased access to capital from financial institutions, and Boubakri et al. (2012) show that these firms have less budget constraints and are less sensitive to competitor pressure than firms without political connections. Moreover, Qian et al. (2011) find that dominant shareholders’ tunnelling and self-dealing activities are more pronounced in politically connected firms when the goal of the connection is to ensure access to bank financing. Chen et al. (2011) find that politically connected firms increase information asymmetries, and Chaney et al. (2011) and Bona et al. (2014) show a lower quality of accounting information in politically connected firms. Additionally, political directors could be an important source of benefits for the company because they provide knowledge on bureaucratic and regulatory procedures (e.g., Agrawal and Knoeber, 2001; Goldman et al., 2009). Faccio (2006) notes that political connections favour preferential treatment for companies in terms of tax benefits, award of government contracts, less regulatory control over the company or greater control over rivals. Thereby, considering the above arguments and the findings of Agrawal and Knoeber (2001), politicians on the board play a “political role”, i.e., they primarily serve as an instrument to promote the systematic exchange of favours between political and business elites (Chaney et al., 2011).

In Continental Europe, the presence of dominant shareholders in large public companies is extensive (e.g., La Porta et al., 1999; Faccio and Lang, 2002). These owners shape the business elite and, therefore, may possess high political and economic influence (e.g., Morck and Yeung, 2004; Morck et al., 2004). In this context, dominant owners have the ability and incentive to play an active role in designing the corporate governance system (e.g., Shleifer and Vishny, 1997; La Porta et al., 1999, 2000; Cuervo, 2002; Burkart et al., 2003; Villalonga and Amit, 2006). This is particularly true of boards of directors because dominant owners have the power to influence board composition, defining the different roles that encompass this internal governance device (e.g., Yeh and Woidtke, 2005; Durnev and Kim, 2005; Kim et al., 2007; Dahya et al., 2008).

As such, the aim of this paper is to analyze the relationship between the presence of political directors on the board and dominant owners’ effective control, as well as to study the effect of political connections on firm value. For this purpose, we used a sample of non-financial Spanish firms listed on the Spanish Stock Exchange over the period 2003–2012. Moreover, we used the control chain methodology to identify the dominant owner for each firm and determine if said owner exercises effective control through a pyramidal structure (e.g., La Porta et al., 1999; Claessens et al., 2000; Faccio and Lang, 2002; Santana and Aguiar, 2006; Sacristán and Gómez, 2007; Pindado et al., 2012). The study of board composition and ownership structure is conducted for each year and firm in the sample to reduce problems associated with the assumption that the ownership structure remains stable over the entire sample period. Another feature of this study is that the unit of analysis is the company and not the country, thereby reducing the problems related to international studies of corporate governance that address different legal, regulatory and institutional frameworks, which make it complicated to distinguish firm-level effects on the results achieved from country-level effects (King and Santor, 2008). In this line, Faccio (2010) argues that the costs and benefits of political connections depend on the specific characteristics of each country.

The results of this study reveal that around half of listed Spanish companies have at least one ex-politician on its board of directors. Furthermore, the results indicate that both the dominant owner's voting rights and his/her family nature affect the likelihood that an ex-politician might be appointed as director. Moreover, the results show that the presence of a politically connected board positively affects firm value. Further analysis shows that this incidence is dependent upon the nature of the dominant owner, the use of pyramidal structures, the political director's tenure and his/her ownership stake.

Our study contributes to the literature on the effect of political ties and board composition in three ways. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that focuses on the presence of political directors over a large time period (ten years) in a country in Continental Europe. Second, it is the first work that analyses the relationship between the power of dominant owners and the presence of politicians on the board of directors in a country without a planned economy. In this sense, the study shows the power of the dominant owners in determining the composition of the board of directors and defining the different roles played by the appointed directors. The results are particularly relevant for increasing the knowledge of factors that determine the composition of the board in environments with concentrated ownership. In this line, Hermalin and Weisbach (1988) argue that to understand how board members are elected it is crucial to understand the role that the board plays in the whole system of corporate governance. Third, most studies on the impact of political connections on firm value have focused on the Anglo-Saxon countries or on the Asian environment using an event methodology and small samples; therefore, their results are hardly generalizable (Cooper et al., 2010).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In section “Theoretical arguments”, we develop our hypotheses on the relationship between firms’ political connections and dominant owners. In section “Research design”, we describe our research design, and in section “Results” we present our empirical results. Finally, in the last section, we provide a summary and conclusion.

Theoretical argumentsPolitical connections and dominant ownersThe previous literature does not provide conclusive results regarding the characteristics of a country that favours links between politicians and businesses. Thus, authors such as Faccio (2006) and Chen et al. (2011) argue that political connections are stronger and more common in countries with weak legal systems and high levels of corruption. However, political connectivity is also relevant in democratic governments because the greater transparency of political connections facilitates the detection of undesirable acts and the implementation of sanctions. Morck et al. (2000) show a large number of political connections in Canadian companies, and Goldman et al. (2009) and Cooper et al. (2010) demonstrate the high political connectivity of U.S. companies. Thereby, business elites have incentives to interact with the political arena in order to affect the development of the legal framework and economic development conditioning the distribution of capital and investment in an economy (La Porta et al., 1998).

The presence of dominant owners facilitates the exchange of favours with political elites, as the concentration of ownership offers the necessary stability to negotiate favours with politicians. On the contrary, this continuity is not guaranteed if control is held by managers or shareholders with a low ownership stake. Thus, Morck et al. (2004) argue that the stability provided by ownership concentration facilitates the collusion between business and political elites. For these authors, the existence of dominant owners allows the presence of an oligarchic capitalism that encourages the development of political lobbying to preserve their status quo. Chen et al. (2011) argue that ownership concentration provides benefits to the relationship between firms and politicians. Therefore, ownership concentration increases the homogeneity of shareholder interests and reduces the costs of carrying out collective actions to establish and maintain connections with the political elites, assuring that the benefits from the connection established by the dominant owner is not diluted by the participation of other shareholders. Finally, the concentration of ownership reduces the need to transfer information on political rents that benefit both dominant owners and politicians, as both have interests in keeping the exchange of favours hidden. Consequently, the concentration of ownership in the hands of a shareholder increases her/his ability to set up private channels with political elites because politicians and entrepreneurs have incentives to provide opacity to their relationships (e.g., Leuz and Oberholzer-Gee, 2006; Bona et al., 2014).

Additionally, previous literature indicates that, outside the Anglo-Saxon environment, dominant owners use pyramid structures to acquire power (e.g., La Porta et al., 1999; Claessens et al., 2000; Faccio and Lang, 2002). These structures allow controlling shareholders to retain control with relatively low levels of investment (Cuervo, 2002). In addition, pyramidal structures facilitate the stability of the dominant owner's control because these devices help him/her defend his/her position (e.g., Amoako-Adu and Smith, 2001; Daines and Klausner, 2001; Santana et al., 2009). Therefore, pyramids reduce transaction costs in developing lobbying policies (Morck et al., 2004). Khanna and Palepu (2000) argue that pyramidal structures allow for the coordination of favours and trust and enable economies of scale through the use of reputation in the relationship between corporate and political elites. This may be of particular interest when the capital markets are less developed and trust relationships are needed to complete contracts.

However, the stability in a company's power is not solely determined by the ownership stake or control through a pyramidal group. In this sense, the nature of the dominant owner may influence the relevance attached to stability in control. Anderson and Reeb (2003) argue that family owners tend to maintain long-term control of a company as a large part of their family wealth is linked to company wealth. Consequently, as a result of their position, family elites may obtain non-pecuniary benefits from political ties. In addition to political rents, family elites can also obtain political influence, social status or a higher degree of impunity in the absence of legal compliance (Morck, 2009).

Nevertheless, in Continental Europe and particularly in Spain, family owners are not the only dominant owners that have traditionally been part of the “oligarchy” of controlling shareholders. Families have shared this role with banks, which have participated significantly in the ownership of listed Spanish firms and have played an active role in corporate governance (Ruiz and Santana, 2011). In this environment, banks have had a significant influence on Spanish economic development and the way of doing business (e.g., Cuervo, 1991; Steinherr and Huveneers, 1994; Zoido, 1998; Fernández, 2001). Beck et al. (2000) argue that financial intermediaries modify the evolution of economic growth because they can influence the distribution of financing as well as technological change and productivity growth. Consequently, in Europe, the dominance of a few large banks facilitates the formation of coalitions and stronger relationships between the state and the banking system (Rajan and Zingales, 2003).

In this context, the dominant owners have the ability and the incentives to influence the design of the corporate governance system, particularly regarding the composition of the board and the different roles of board members (e.g., Yeh and Woidtke, 2005; Durnev and Kim, 2005; Kim et al., 2007; Dahya et al., 2008). Thus, board structure is shaped by the costs and benefits derived from company control and the directors’ ability to advise internal agents (Li et al., 2008). In this sense, when the dominant owner stably controls a significant capital stake, he/she will be more likely to use private channels with political elites because the dominant owner will benefit less from having a political director on the board as it increases scrutiny over company performance (e.g., Riahi-Belkaoui, 2004; Chaney et al., 2011; Boubakri et al., 2012). Therefore, it is expected that the relationship between the dominant owner's control and the presence of a politically connected board would be negative. Therefore, our first hypothesis is as follows:Hypothesis 1 Control in the hands of the dominant shareholder has a negative influence on the probability of having a politically connected board.

Previous literature suggests several motivations for the existence of political connections, including access to privileged financing sources, subsidies or the use of contacts and knowledge to obtain favours when developing new regulations or participating in contracts with government authorities (e.g., Agrawal and Knoeber, 2001; Goldman et al., 2009). Moreover, Faccio (2006) argues that political ties can lead to preferential government treatment through, for instance, increased access to bank financing, lower tax rates, more government contract awards and less regulatory oversight of the connected firm or greater oversight of the connected firm's rivals. Boubakri et al. (2012) show that these firms have fewer budget constraints and are less sensitive to competition pressure than firms without political connections. Duchin and Sosyura (2012) show that politically connected firms receive more public investment.

Therefore, maintaining a relationship with the political elite over time is a strategy that can generate value for a company. Fisman (2001) shows that the market value of Indonesian firms closely related to President Suharto's family experienced a significant decrease upon the release of negative news about the president's health. Similarly, Faccio and Parsley (2009) find a significant decrease in firm value after the death of politicians residing or born in the same geographic area as the head company. In addition, Goldman et al. (2009) show that corporate donations are a less reliable indicator of future performance that the presence of political directors on the board.

Moreover, an environment of ownership concentration and a weak legal system increases the importance of personal networks and reputation as valuable instruments for attenuating expropriation of minority shareholders’ wealth by the dominant shareholders (e.g., Agrawal and Knoeber, 2001; Stafsudd, 2009). In this sense, politically connected firms may be subject to greater scrutiny by financial analysts and the media (e.g., Riahi-Belkaoui, 2004; Chaney et al., 2011; Boubakri et al., 2012). This scrutiny can lead to greater alignment between controlling and minority shareholders’ interests because of the greater importance that stability in control and reputation acquire in this scenario.

However, political connections can be established to achieve goals other than value generation, especially in environments where shareholders are not sufficiently protected by the legal system and dominant owners can benefit from political rent-seeking. Therefore, Morck et al. (2004) consider the presence of an “oligarchic capitalism” in concentrated ownership environments as an incentive for political and business elites to preserve the status quo at the expense of other stakeholders’ interests.

Qian et al. (2011) suggest that political connections can shape dominant owners’ incentive to expropriate minority shareholders because these connections limit capital market discipline. Consequently, as these authors indicate, the possibility of obtaining funds outside the financial market can provide greater incentives to carry out expropriation activities. Therefore, Qian et al. (2011) found that dominant owners’ tunnelling and self-dealing activities are more pronounced in firms where political connection aims to secure bank loan access. For these authors, dominant owners’ expropriation activities face a possible trade-off between short-term benefits and long-term costs arising from the loss of corporate reputation. In this context, this cost depends on future investment opportunities and the financial resources available to fund them. Accordingly, when political connections are established to ensure access to financing sources outside of the capital markets, dominant owners are less concerned about the loss of reputation and will have a greater incentive to obtain private benefits.

Therefore, the above arguments highlight the importance of considering the environment in which political connections are established because the environment could affect not only the purpose of such connections but also their costs and benefits. Faccio (2010) shows that the differences between connected and unconnected firms are greater in institutional environments characterized by weak protection of external shareholders and that the costs and benefits of political connections depend on the particular characteristics of the institutional environment. Consequently, the above arguments predict opposite effects regarding the relationship between political connections and firm value. Therefore, our second hypothesis isHypothesis 2 Political connections will affect the firm value. Political connections have a positive effect on the firm value. Political connections have a negative effect on the firm value.

The initial sample comprises 115 non-financial firms listed on the Spanish Stock Exchange between 2003 and 2012. In our regression analysis, we apply the method developed by Hadi (1994) to eliminate outliers. As a result, we obtain an unbalanced panel of 999 firm-year observations, with 95% of the firms having six or more observations over the 2003 to 2012 period.

DataWe hand-collect data on board composition and ownership structure, as well as additional information on the economic characteristics of the companies analyzed, for each year of the analyzed period. Thus, we have obtained the financial data from the financial information of listed companies published by the Spanish Securities Exchange Commission (CNMV). We examine the Curriculum Vitae of the board members from the Annual Corporate Governance Reports published by the Spanish Security Exchange Commission and from the firms’ websites. When this information was not available, we asked the firms directly.

Finally, consistent with previous research focused on the Spanish business environment (e.g., Santana and Aguiar, 2006; Sacristán and Gómez, 2007; Ruiz and Santana, 2009, 2011), variables related to the level of voting rights, the nature of the dominant owners and the use of pyramidal structures have been obtained by using the control chain methodology to identify the dominant owner of the company, measure her/his voting and cash flows rights and identify the global structure through which that owner controls the company (e.g., La Porta et al., 1999; Claessens et al., 2000; Faccio and Lang, 2002; Santana and Aguiar, 2006; Sacristán and Gómez, 2007; Pindado et al., 2012). Consequently, a firm has a dominant owner if the main shareholder directly or indirectly holds a percentage of voting rights equal to or above an established level of control, which, consistent with previous literature, is 20%. Therefore, the identification of a family or a bank as the dominant owner through the use of this methodology prevents mistakes that are prevalent in concentrated ownership environments, such as assigning a shareholder a level of voting and cash flow rights that does not correspond with his/her real holding. Moreover, this methodology prevents the researcher from identifying a shareholder as a dominant owner when he/she does not actually occupy the final position in the control chain. To identify such ownership–control relationships, we hand-collect ownership data to allow us to identify a firm's entire ownership control chain for each sample year. We start with information on significant shareholdings published by the Spanish Securities Exchange Commission, which includes data on the direct and indirect participation of shareholders that own at least 5% of a firm's shares, as well as ownership in the hands of the board, regardless of the size of the holding. Next, we complement these data with the Amadeus database (Bureau Van Dijk), which publishes information on board of directors and ownership structure for Spanish listed and non-listed firms. For those cases in which a non-Spanish holds shares of a Spanish firm, we complete our mapping of the ownership structure by examining the firms’ annual reports published online and resolving any remaining question vía email.

VariablesTo analyze the likelihood that a firm is politically connected, we define POLITICIANS as a dummy variable that takes the value of one if at least one of the members of the board of directors has held a political position at the European, Spanish, regional or local level in the past; otherwise, the value is zero. This approach is consistent with previous literature (e.g., Faccio, 2006; Goldman et al., 2009; Chaney et al., 2011; Boubakri et al., 2012; Duchin and Sosyura, 2012; Bona et al., 2014). As an example, we classify the firm Gas Natural as a politically connected firm in 2012 because at least one of the board members had previously held a leadership position in politics. Namely, Mr. Felipe González Márquez was the President of the Spanish Government from 1982 to 1994. Another politically connected firm is Vueling, as board member Mr. Josep Piqué Camps held several political positions in the Spanish government from 1996 to 2003. Thus, as in the previous work, this study focuses on revolving door cases, identifying politicians who enter the private sector as director of a listed company.

The study of the effect of political connections on firm value has been accomplished by using a measure that reflects investor expectations about the ability of the company to produce future earnings. Thus, we define Q.TOBIN as the ratio of the market value of the firm to the book value of its assets (e.g., Morck et al., 1988; McConnell and Servaes, 1990; Cho, 1998; Demsetz and Villalonga, 2001; López and Rodríguez, 2001; Claessens et al., 2002; Seifert et al., 2005; Villalonga and Amit, 2006; Ferreira and Matos, 2008; Ruiz and Santana, 2011).

Therefore, in relationship to the effect of POLITICIANS on firm value, the above theoretical arguments show potential positive and negative impacts on the political connection-value relationship (e.g., Agrawal and Knoeber, 2001; Fisman, 2001; Faccio, 2006; Faccio and Parsley, 2009; Stafsudd, 2009). Consequently, the theoretical arguments do not allow us to expect a particular sign in the relationship between POLITICIANS and firm value.

Moreover, to further explore this relationship, we define the variables POLITICIANS_Famy, POLITICIANS_Bank and POLITICIANS_Pyramid as dummy variables that take the value of 1 if at least one of the board members has held a political position at the European, Spanish, regional or local level in the past and the dominant owner is a family, a bank or control the firm through a pyramid, respectively; otherwise, the value is zero. We define the variable POLITICIANS_TENURE as a measurement of the average tenure of political directors as board members and the variable POLITICIANS_OWN as a measurement of the percentage of voting rights held by political directors. The effect of these two variables on the value of the company will be analyzed in linear and quadratic terms because the theoretical arguments and opposite empirical results in previous literature invite us to analyze this incidence for different political directors’ tenures and ownership stakes.

The remaining corporate governance variables used in the analysis of the likelihood that a company decides to establish political connections are detailed below. The variable VOTING is measured as voting rights in the hands of the dominant owner. The variables FAMILY and BANK are dummy variables that take the value of one if the dominant owner is a family or a bank, respectively; otherwise, the value is zero. The effect of the use of pyramidal structures on the probability that a company will establish a political connection is tested using the variable PYRAMID, a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 when dominant owner control is exercised through a pyramidal structure; otherwise, the value is zero. Based on the theoretical arguments set out in Hypothesis 1, we expect the effect of previous variables on the likelihood of having a politically connected board to be negative.

To control for the effect of other variables that could potentially affect the investigated relationship, we include SIZE, measured as the natural logarithm of the total assets. Therefore, consistent with the previous literature, we expect firm size to positively affect the likelihood of establishing a political connection (e.g., Agrawal and Knoeber, 2001; Faccio, 2006; Faccio et al., 2006; Boubakri et al., 2008; Cooper et al., 2010). Moreover, authors such as Khwaja and Mian (2005), Boubakri et al. (2012) and Cooper et al. (2010) show that politically connected firms are characterized by the use of a higher level of debt; therefore, we include the variable DEBT, measured as total debt divided by total assets as a control variable. Moreover, Cooper et al. (2010) and Chen et al. (2011) show that politically connected firms are characterized by higher profitability and greater investment opportunities. For this reason, we include the effect of growth opportunities MTB, defined as the market value of equity divided by the book value of equity. Additionally, to control for the effect of the bargaining power of the president of the board, we include the variable PRESI_DUAL as a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the president of the board has an executive role and zero otherwise. Following the arguments of Chen et al. (2011), we expect this duality to positively affect the likelihood of having a politically connected board, as the concentration of power facilitates negotiation with politicians and reduces the risks derived from sharing information about the real benefits of the political connection. Finally, we use dummy variables to control the possible industry and time effects on the likelihood that a firm will establish a political connection.

ResultsDescriptive statisticsTable 1 shows the evolution of political connections in Spanish listed companies for the period 2003–2012. Thus, the table details the percentage of politically connected firms, both when considering ex-politicians at local, regional, national and European levels and when analysing only high-level politicians, i.e., those who have held positions at the national or European level. The results show that around half of the listed companies have at least one director who has held a political position. In addition, high-level politicians are present in 46% of the companies analyzed. These results are not consistent with those obtained in Faccio's study (2006), in which the author finds that only 1.5% of Spanish companies are politically connected. This discrepancy may be due to Faccio's data. In fact, the previous author uses data from 2001, a year in which the level of transparency about the governance practices of Spanish listed companies was limited. In addition, Faccio analyzed the composition of the board through the Worldscope database, which only reports information about the President, Vice President, CEO and Secretary.

Politically connected firms in the Spanish stock market.

| 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of political directors (%) | ||||||||||

| Politically connected firmsa | 51.19 | 50.57 | 55.43 | 54.00 | 55.36 | 53.57 | 54.63 | 57.69 | 56.44 | 52.53 |

| Politically connected firms (only high-level politicians)b | 48.81 | 47.13 | 48.91 | 45.00 | 45.54 | 44.64 | 42.59 | 44.23 | 46.53 | 47.47 |

| Types of political directors (%) | ||||||||||

| Independents | 65 | 66.1 | 65.6 | 65.1 | 69.6 | 70.4 | 73.1 | 75 | 75.8 | 75.4 |

| Significant shareholder representatives | 21.7 | 20.4 | 22.9 | 22.2 | 18.8 | 19.8 | 19.5 | 17.6 | 16.6 | 14.8 |

| Executives | 13.3 | 13.5 | 11.5 | 12.7 | 11.6 | 9.8 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 9.8 |

| Characteristics of political directors | ||||||||||

| Tenure of political director (years) | 5.63 | 6.15 | 5.81 | 6.05 | 5.71 | 6.15 | 6.18 | 6.32 | 6.93 | 7.45 |

| Ownership of political directors (%) | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.26 |

| Politically connected firms and regulated industries (% of firms) | ||||||||||

| Regulated industriesc | 62.50 | 60.00 | 61.54 | 58.06 | 62.16 | 62.16 | 62.86 | 64.71 | 63.64 | 54.84 |

| Non-regulated industries | 46.67 | 46.77 | 53.03 | 52.17 | 52.00 | 49.33 | 50.68 | 54.29 | 52.94 | 51.47 |

| Politically connected firms and industry (% of firms) | ||||||||||

| Oil and energy | 87.5 | 75 | 87.5 | 100 | 72.7 | 72.7 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Consumer goods | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 40.9 | 36.4 | 33.3 | 35 | 30.7 | 28.6 |

| Consumer services | 62.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 55.6 | 63.6 | 63.6 | 63.6 | 63.6 | 63.6 | 45.4 |

| Basic materials, Industry and Construction | 48.3 | 48.3 | 51.7 | 53.3 | 54.8 | 51.6 | 53.1 | 60 | 62.1 | 62.1 |

| Real Estate Agencies | 37.5 | 44.4 | 40 | 35.7 | 53.3 | 53.3 | 42.8 | 42.8 | 42.8 | 36.4 |

| Transport and telecoms | 45.4 | 46.1 | 64.7 | 57.9 | 59.1 | 59.1 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 57.8 |

| Number of firms | 84 | 87 | 92 | 100 | 112 | 112 | 108 | 104 | 101 | 99 |

Regarding the typology of political directors, the results show that 70% are independent directors, 20% represent significant shareholders and only 10% have an executive role in the company. Moreover, Table 1 shows that political directors have, on average, six years tenure, showing a growing trend for this variable. Therefore, the average tenure increases from 5.63 years in 2003 to 7.45 years in 2012. These results reflect the stability of political directors in the companies in which they have been appointed. Moreover, these directors hold, on average, 0.2% of the voting rights, keeping this ownership stake stable over the period analyzed.

Concerning the distribution of politically connected firms according to industry, the results show a greater presence of political connections in companies belonging to regulated industries. However, we can observe that the differences between regulated firms and unregulated sectors are decreasing. Thus, if we analyze the sectorial distribution of connected firms according to the classification used by the Madrid Stock Exchange, we note that 100% of boards in the Oil and Energy Industry are politically connected in the last three years analyzed, the increase in politically connected boards in the “Basic Materials, Industry and Construction” industries being relevant. In contrast, Real Estate Agencies and Consumer Goods sectors are less politically connected.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the empirical study. Hence, regarding the ownership variables, the results reflect a 32.08% average ownership stake in the hands of the dominant owner. Moreover, 48.43% of the listed companies are family-controlled, while the domain of a bank is present in around the 12.09%. These percentages are consistent with previous studies focused on the Spanish context (e.g., Santana and Aguiar, 2006; Sacristán and Gómez, 2007; Bona et al., 2011a; Ruiz and Santana, 2011). On average, family firms are controlled by the same family for 91% of the 10 years analyzed (100% in terms of median) and 96.3% of those firms have family members on the board. When the controlling shareholder is a bank, this bank remains in control for 67.6% of the years analyzed (70.7% in terms of median) and 90.32% of this controlling shareholder has representation on the board of directors. Moreover, in 79.92% of the companies, the control of the dominant owner is exercised through a pyramid structure. These results are consistent with those obtained for the Spanish context by Santana and Aguiar (2006), Sacristán and Gómez (2007), Bona et al. (2011a,b) and Ruiz and Santana (2009, 2011). Finally, regarding the presence of political connections, depending on the nature of the dominant owner and the use of pyramid structures, the results show that 63.64% of the companies controlled by a bank have at least one political director. This percentage is reduced to 51.39% for family firms, while approximately 50% of pyramidal structures have at least one political connection on the board of directors.

Descriptive statistics.

| Average | Median | S.D. | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Continuous variables | |||||

| VOTING | 32.08 | 25.08 | 21.12 | 0.82 | 91.30 |

| Q.TOBIN | 1.51 | 1.18 | 1.19 | 0.66 | 7.43 |

| SIZE | 13.89 | 13.66 | 1.87 | 10.42 | 18.35 |

| MTB | 3.24 | 1.74 | 13.75 | 0.91 | 24.03 |

| DEBT | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.92 |

| Panel B. Dummy variables (%) | |||||

| POLITICIANS | 54.25 | ||||

| FAMILY | 48.43 | ||||

| BANK | 12.09 | ||||

| PYRAMID | 79.92 | ||||

| POLITICIANS_Famya | 51.39 | ||||

| POLITICIANS_Banka | 63.64 | ||||

| POLITICIANS_Pyramida | 52.63 | ||||

| PRESI_DUAL | 71.67 | ||||

VOTING is the voting rights in the hands of the dominant owner. Q.TOBIN is the ratio of the market value of the firm to the book value of its assets. SIZE is the natural logarithm of the total assets. MTB is the market value of equity divided by the book value of equity. DEBT is total debt divided by total assets. POLITICIANS is a dummy variable that takes the value of one if at least one of the members of the board of directors has held a political position at the European, Spanish, regional or local level in the past; otherwise, the value is zero. FAMILY and BANK are dummy variables that take the value of one if the dominant owner is a family or a bank, respectively; otherwise, the value is zero. PYRAMID is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 when dominant owner control is exercised through a pyramidal structure; otherwise, the value is zero. POLITICIANS_Famy, POLITICIANS_Bank and POLITICIANS_Pyramid are dummy variables that take the value of 1 if at least one of the board members has held a political position at the European, Spanish, regional or local level in the past and the dominant owner is a family, a bank or control the firm through a pyramid, respectively; otherwise, the value is zero. PRESI_DUAL is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the president of the board has an executive role and zero otherwise.

The descriptive analysis completed in Table 3 reports the correlations among the variables and suggests that multicollinearity does not affect subsequent estimations. Nevertheless, we conduct a formal test to ensure that multicollinearity is not a problem. In particular, we calculate the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for each independent variable included in the estimated model. The results show that the highest VIF value is 4.75, and the average is 1.41 and 2.30 for the study of the variables POLITICIANS and Q.TOBIN, respectively. The highest VIF ratio is well below 5, with the threshold value indicating that multicollinearity might be a problem (Studenmund, 1997). We therefore conclude that multicollinearity is not a problem in our sample.

Correlation matrix and VIF ratios.

| POLÍTICIANS | POLÍTICIANS_Famy | POLÍTICIANS_Bank | POLÍTICIANS_Pyramid | Q.TOBIN | VOTING | FAMILY | BANK | PYRAMID | SIZE | MTB | DEBT | VIF (POLÍTICIANS) | VIF (Q.TOBIN) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POLÍTICIANS | 3.62 | |||||||||||||

| POLÍTICIANS_Famy | 0.67*** | 4.75 | ||||||||||||

| POLÍTICIANS_Bank | 0.26*** | −0.21*** | 2.03 | |||||||||||

| POLÍTICIANS_Pyramid | 0.78*** | 0.74*** | 0.26*** | 4.60 | ||||||||||

| Q.TOBIN | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| VOTING | −0.03 | 0.21*** | −0.08*** | 0.16*** | 0.06** | 1.23 | 1.20 | |||||||

| FAMILY | −0.08*** | 0.50*** | −0.42*** | 0.15*** | −0.04 | 0.34*** | 2.31 | |||||||

| BANK | 0.06** | −0.27*** | 0.77*** | 0.09*** | −0.04 | −0.11*** | −0.54*** | 1.74 | ||||||

| PYRAMID | −0.06** | 0.22*** | 0.05 | 0.42*** | 0.01 | 0.33*** | 0.43*** | 0.08*** | 1.62 | |||||

| SIZE | 0.36*** | 0.17*** | 0.18*** | 0.36*** | −0.14*** | 0.09*** | −0.16*** | 0.15*** | 0.11*** | 1.20 | 1.32 | |||

| MTB | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.08*** | 0.02 | 0.21*** | 0.02 | −0.05* | 0.05* | 0.01 | −0.02 | 1.01 | 1.02 | ||

| DEBT | 0.06** | 0.07** | 0.02 | 0.1*** | 0.09*** | 0.12*** | 0.05* | 0.008 | 0.05* | 0.23*** | 0.02 | 1.08 | 1.08 | |

| PRESI_DUAL | 0.23*** | 0.09*** | 0.07** | 0.14*** | −0.10*** | −0.08*** | −0.08*** | −0.04 | −0.10*** | 0.18*** | −0.07** | 0.10*** | 1.07 | 1.10 |

| Average VIF | 1.41 | 2.30 | ||||||||||||

POLITICIANS is a dummy variable that takes the value of one if at least one of the members of the board of directors has held a political position at the European, Spanish, regional or local level in the past; otherwise, the value is zero. POLITICIANS_Famy, POLITICIANS_Bank and POLITICIANS_Pyramid are dummy variables that take the value of 1 if at least one of the board members has held a political position at the European, Spanish, regional or local level in the past and the dominant owner is a family, a bank or control the firm through a pyramid, respectively; otherwise, the value is zero. Q.TOBIN is the ratio of the market value of the firm to the book value of its assets. VOTING is the voting rights in the hands of the dominant owner. FAMILY and BANK are dummy variables that take the value of one if the dominant owner is a family or a bank, respectively; otherwise, the value is zero. PYRAMID is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 when dominant owner control is exercised through a pyramidal structure; otherwise, the value is zero. SIZE is the natural logarithm of the total assets. MTB is the market value of equity divided by the book value of equity. DEBT is total debt divided by total assets. PRESI_DUAL is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the president of the board has an executive role and zero otherwise.

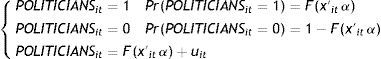

To test Hypothesis 1, we have performed two specifications. First, we have estimated a Probit multivariate panel model whose dependent variable is POLITICIANS, defined as a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 when at least one of a company's directors has held a political position at the European, Spanish, regional or local level; otherwise, the value is zero. Thus, we have estimated a binary choice model whose probability should be between 0 and 1. Therefore, the probability that a company has a political advisor is determined by the following distribution:

where (x'itα) is the vector of parameters to estimate and uit is the error term. Thus, to test Hypothesis 1, we have performed the specification of the vector of parameter and the error term of the initial model as follows:Therefore, the variable δk estimates the industry effect and the variable θj estimates the year effect, both through dummy variables. Second, we have specified a Probit model with instrumental variables to solve potential endogeneity problems. In this sense, the concentration of voting rights can influence the presence of politicians on the board, but it is also possible that the presence of politicians leads to a greater concentration of power in the hands of the dominant owner. In this model we consider ownership as an endogenous variable that is estimated using a set of instrumental variables Zit uncorrelated with the error term.1Table 4 shows the results of estimating the Probit models and the consideration of the endogeneity of the variables by estimating a Probit model with instrumental variables. In this sense, exogeneity tests show a more adequate estimation in Probit models with instrumental variables, with the exception of the analysis of pyramidal structures (models 4 and 8). Accordingly, consistent with Hypothesis 1, the results suggest that voting rights and the family nature of the dominant owner have a significant negative influence on the probability that the board has at least one political director. In addition, the estimated coefficients in Model 6 indicate that participation in the voting rights of the dominant family does not affect the likelihood of establishing political connections on the board of directors; i.e., the negative impact of family control on the probability of establishing political ties through the presence of political directors is independent of the voting rights in the hands of the dominant family.2 Moreover, the estimates indicate that the banking nature of dominant owners and the use of pyramidal structures do not significantly affect the likelihood of having a politically connected board.

Political directors and dominant owner.

| Estimated sign | Probit multivariate panel models | Probit models with instrumental variables | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | ||

| VOTING | − | −0.174**(−2.00) | −0.048**(−2.20) | −0.018**(−2.03) | −0.010*(−1.71) | −0.024**(−2.43) | −0.054**(−2.53) | −0.026**(−2.41) | −0.023(−0.27) |

| FAMILY | − | 0.323(0.58) | −1.142**(−2.53) | ||||||

| VOTING X FAMILY | − | 0.033(1.48) | 0.054**(2.50) | ||||||

| BANK | − | −0.600(−0.68) | −0.563(−1.27) | ||||||

| VOTING X BANK | − | −0.014(−0.43) | 0.016(1.14) | ||||||

| PYRAMID | − | 0.343(0.57) | 0.020(0.1) | ||||||

| VOTING X PYRAMID | − | −0.007(−0.27) | −0.021(−0.25) | ||||||

| SIZE | + | 0.821***(4.59) | 1.408***(5.28) | 0.8445***(4.51) | 1.311***(5.18) | 0.226***(6.62) | 0.244***(7.4) | 0.226***(6.31) | 0.243***(7.43) |

| MTB | + | 0.0002(0.04) | 0.060(0.48) | 0.001(0.24) | 0.076(0.64) | 0.004(1.05) | 0.004(1.24) | 0.004(1.13) | 0.004(1.01) |

| DEBT | + | 0.966**(2.41) | −0.103(−0.09) | 0.991**(2.47) | 0.168(0.14) | 0.020(0.10) | 0.238(1.34) | 0.007(0.4) | 0.226(1.05) |

| PRESI_DUAL | + | 1.639***(4.64) | 1.855 ***(4.52) | 1.594***(4.33) | 1.772***(4.54) | 0.361**(2.48) | 0.295*(1.77) | 0.326**(2.02) | 0.525***(4.77) |

| Industry effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Constant | −12.623***(−5.34) | −19.687***(−5.98) | −12.991***(−5.35) | −18.498***(−5.72) | −2.695***(−4.23) | −2.305***(−3.01) | −2.607***(−3.68) | −3.647**(−2.29) | |

| Long pseudo–likelihood | −292.987 | −243.410 | −291.763 | −249.722 | −492.75 | 418.55 | 490.71 | 403.15 | |

| Wald χ2 | 86.42*** | 83.58*** | 86.78*** | 87.89*** | 291.23*** | 278.36*** | 308.74*** | 240.42*** | |

| Test rho=0 | 501.58*** | 428.85*** | 507.65*** | 407.67*** | |||||

| Test Wald of exogeneity | 3.56* | 3.07* | 3.39* | 0.14 | |||||

Dependent variable: POLITICIANS is a dummy variable that takes the value of one if at least one of the members of the board of directors has held a political position at the European, Spanish, regional or local level in the past; otherwise, the value is zero. VOTING is the voting rights in the hands of the dominant owner. FAMILY and BANK are dummy variables that take the value of one if the dominant owner is a family or a bank, respectively; otherwise, the value is zero. PYRAMID is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 when dominant owner control is exercised through a pyramidal structure; otherwise, the value is zero. SIZE is the natural logarithm of the total assets. MTB is the market value of equity divided by the book value of equity. DEBT is total debt divided by total assets. PRESI_DUAL is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the president of the board has an executive role and zero otherwise.

Thus, the results indicate that the dominant owner's level of voting rights and some qualitative aspects linked to family control influence board composition and, in particular, the presence of political directors. Thus, our results are consistent with previous studies that show dominant owners having an active role in the design of the governance system and, in particular, board composition (e.g., Yeh and Woidtke, 2005; Durnev and Kim, 2005; Kim et al., 2007; Dahya et al., 2008).

Regarding the control variables, the results are as expected when we consider the size of the company and the dual role of president of the board and chief executive, in that both variables positively and significantly affect the likelihood of having a politically connected board. However, the results do not show a statistically significant effect of either debt or investment opportunities on propensity to have a politically connected board.

Political directors and firm valueThe test of the hypothesis related to the effect of political connections on firm value has been performed by estimating regressions using the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM). The GMM procedure allows us to address potential endogeneity problems by using the right-hand-side variables in the model lagged as instruments; the only exceptions are the year and industry effects variables, which are considered exogenous. The original Arellano and Bond (1991) approach can perform poorly, however, if the autoregressive parameters or the ratio of the variance of the panel-level effect to the variance of the idiosyncratic error are too large. Drawing on Arellano and Bover (1995), Blundell and Bond (1998) develop a system GMM estimator that addresses these problems by expanding the instrument list to include instruments for the level equation. The consistency of GMM estimates depends on both an absence of second-order serial autocorrelation in the residuals and on the validity of the instruments. To check for potential model misspecification, we use the Hansen statistic of over-identifying restrictions. We next examine the m2 statistic developed by Arellano and Bond (1991) to test for the absence of second-order serial correlation in the first difference residual. Finally, we conduct three Wald tests, specifically, a Wald test of the joint significance of the reported coefficients (z1), a Wald test of the joint significance of the industry dummies (z2) and a Wald test of the joint significance of the time dummies (z3). Therefore, the specification of the initial model used to test Hypothesis 2 is as follows:

Thus, model 9 (Table 5) shows the presence of political directors to have a positive and significant effect on firm value, which is consistent with Hypothesis 2a. Furthermore, to extend the analysis of the effect of political connections on firm value in Models 10, 11 and 12, we analyze the effect of political connections on firm value when the dominant owner is a family, bank or control is exercised through a pyramid structure, respectively. Thus, the results are consistent with Hypothesis 2a in the case of family firms and when control is exercised through a pyramid, while when a bank is the dominant owner, the political connection negatively affects firm value as Hypothesis 2b predicts. In this line, we estimate the effect of directors’ tenure on firm value. The results show a nonlinear relationship (+/−) between directors’ tenure and firm value (model 13). Finally, we completed the analysis with model 14, which estimates the effect of ownership in the hands of political directors on firm value. The results show a nonlinear relationship (−/+) between both variables.

Political connections and firm value.

| Estimated sign | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POLITICIANS | +/− | 0.177***(7.64) | 0.139***(2.65) | 0.185***(5.43) | 0.312***(3.15) | ||

| FAMILY | +/− | 0.155***(3.89) | |||||

| POLITICIANS_Famy | +/− | 0.081*(1.75) | |||||

| BANK | +/− | −0.121***(−2.62) | |||||

| POLITICIANS_Bank | +/− | −0.167***(−3.56) | |||||

| PYRAMID | +/− | 0.046(0.55) | |||||

| POLITICIANS_Pyramid | +/− | 0.268**(2.21) | |||||

| POLITICIANS_TENURE | +/− | 0.022***(11.56) | |||||

| POLITICIANS_TENURE2 | +/− | −0.001***(−12.19) | |||||

| POLITICIANS_OWN | +/− | −0.063***(−9.23) | |||||

| POLITICIANS_OWN2 | +/− | 0.005***(10.22) | |||||

| SIZE | − | −0.047***(−7.29) | −0.079***(−5.78) | −0022**(−2.19) | −0.222***(−11.59) | −0.046***(−6.88) | −0.028***(−8.43) |

| DEBT | + | 0.323***(6.67) | 0.55***(6.65) | 0.137*(1.79) | 0.260***(11.41) | 0.176**(2.21) | 0.158***(3.78) |

| MTB | + | 0.009***(16.08) | 0.001***(8.31) | 0.001***(9.69) | 0.019***(16.75) | 0.009***(8.41) | 0.002**(2.57) |

| PRESI_DUAL | +/− | 0.154***(9.84) | 0.049(1.14) | 0.115***(6.05) | 0.358***(4.48) | 0.0786***(4.89) | 0.171***(14.38) |

| Industry effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Constant | 0.916***(7.94) | 1.239***(6.42) | 1.50***(7.92) | 1.624***(7.43) | 1.204***(10.32) | 0.898***(9.36) | |

| F | 1712.65*** | 3156*** | 2766.36*** | 210.58*** | 802.11*** | 1050.4*** | |

| M2 | 0.60 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.23 | 0.66 | 0.30 | |

| Z1 | 162.90*** | 189.17*** | 35.38*** | 169.78*** | 53.14*** | 104.58*** | |

| Z2 | 77.06*** | 154.95*** | 59.45*** | 25.84*** | 66.46*** | 44.41*** | |

| Z3 | 260.24*** | 168.15*** | 101.75*** | 45.02*** | 327.58*** | 154.01*** | |

| Hansen test | 101.01 (103) | 87.76 (140) | 96.71 (178) | 64.29 (62) | 89.62 (125) | 97.67 (124) | |

Dependent variable: Q.TOBIN, is the ratio of the market value of the firm to the book value of its assets. POLITICIANS, is a dummy variable that takes the value of one if at least one of the members of the board of directors has held a political position at the European, Spanish, regional or local level in the past; otherwise, the value is zero. FAMILY and BANK are dummy variables that take the value of one if the dominant owner is a family or a bank, respectively; otherwise, the value is zero. PYRAMID, is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 when dominant owner control is exercised through a pyramidal structure; otherwise, the value is zero. POLITICIANS_Famy, POLITICIANS_Bank and POLITICIANS_Pyramid are dummy variables that take the value of 1 if at least one of the board members has held a political position at the European, Spanish, regional or local level in the past and the dominant owner is a family, a bank or control the firm through a pyramid, respectively; otherwise, the value is zero. POLITICIANS_TENURE, is the average tenure of political directors as board members. POLITICIANS_OWN, is the percentage of voting rights held by political directors. VOTING, is the voting rights in the hands of the dominant owner. SIZE, is the natural logarithm of the total assets. DEBT, is total debt divided by total assets. MTB, is the market value of equity divided by the book value of equity. PRESI_DUAL, is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the president of the board has an executive role and zero otherwise. Hansen, test of over-identifying restrictions, under the null hypothesis that all instruments are uncorrelated with the disturbance process. m2, statistic test for lack of second-order serial correlation in the first-difference residual. z1, Wald test of the joint significance of the reported coefficients. z2, Wald test of the joint significance of the industries dummies. z3, Wald test of the joint significance of the time dummies. In parentheses, t-statistics based on robust standard errors.

Regarding the control variables, the results indicate that firm size has a negative impact on value, which is consistent with the higher agency problems associated with larger companies. However, debt level, investment opportunities and the dual role of president of the board positively affect firm value.

Sensitivity analysisTo determine the robustness of our results, we first analyze the likelihood of having a politically connected board through the use of high-level politicians. Therefore, we define the variable POLITICIANS_HIGH as a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 when at least one director has held a political position at the European or Spanish level and zero otherwise. The results shown in Table 6 are consistent with those obtained when we analyzed all politicians.

Political connections and dominant owner (sensitivity analysis).

| Robit multivariate panel models | Probit models with instrumental variables | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (15) | (16) | (17) | (18) | (19) | (20) | (21) | (22) | |

| VOTING | −0.018**(−2.23) | −0.049***(−2.60) | −0.017**(−1.97) | −0.021*(−1.76) | −0.024***(−2.68) | −0.056***(−2.85) | −0.027***(−2.68) | −0.081(−0.78) |

| FAMILY | −0.076(−0.15) | −1.305***(−3.22) | ||||||

| VOTING X FAMILY | 0.034*(1.72) | 0.056***(2.82) | ||||||

| BANK | 0.177(0.21) | −0.405(−0.92) | ||||||

| VOTING X BANK | −0.034(−1.06) | 0.017(1.24) | ||||||

| PYRAMID | 0.072(0.14) | −1.66(−0.95) | ||||||

| VOTING X PYRAMID | 0.003(0.13) | 0.081(0.76) | ||||||

| SIZE | 0.825***(4.87) | 0.853***(4.91) | 0.828***(4.80) | 0.823***(4.85) | 0.225***(6.54) | 0.234***(7.14) | 0.218***(6.12) | 0.136***(5.70) |

| MTB | −0.0008(−0.19) | 0.0001(0.03) | 0.00005(0.01) | −0.0008(−0.18) | 0.004(1.11) | 0.005(1.25) | 0.004(1.10) | 0.004(0.85) |

| DEBT | 1.318**(2.51) | 1.367***(2.56) | 1.344**(2.54) | 1.330**(2.52) | 0.187(0.94) | 0.451***(2.65) | 0.195(0.99) | 0.172(0.35) |

| PRESI_DUAL | 0.707**(2.29) | 0.649 **(2.03) | 0.621*(1.94) | 0.716**(2.31) | 0.294**(2.13) | 0.211(1.35) | 0.269*(1.76) | 0.225(0.46) |

| Industry effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −13.191***(−5.69) | −13.567***(−5.61) | −13.286***(−5.68) | −13.246***(−5.58) | −2.664***(−4.17) | −2.202***(−2.71) | −2.497***(−3.56) | −0.602(−0.12) |

| Long pseudo-likelihood | −292.073 | −287.722 | −289.851 | −292.014 | 494.39 | 420.13 | 492.26 | 405.19 |

| Wald χ2 | 85.24*** | 85.54*** | 87.61*** | 85.49*** | 278.27*** | 289.64*** | 297.67*** | 395.86*** |

| Test rho=0 | 540.82*** | 545.30*** | 543.11*** | 536.41*** | ||||

| Test Wald of exogeneity | 4.10** | 4.27** | 4.06** | 0.27 | ||||

Dependent variable: POLITICIANS_HIGH is a dummy variable that takes the value of one if at least one of the members of the board of directors has held a political position at the European or Spanish level in the past; otherwise, the value is zero. VOTING is the voting rights in the hands of the dominant owner. FAMILY and BANK are dummy variables that take the value of one if the dominant owner is a family or a bank, respectively; otherwise, the value is zero. PYRAMID is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 when dominant owner control is exercised through a pyramidal structure; otherwise, the value is zero. SIZE, is the natural logarithm of the total assets. MTB is the market value of equity divided by the book value of equity. DEBT is total debt divided by total assets. PRESI_DUAL is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the president of the board has an executive role and zero otherwise.

Moreover, regarding the study of the effect of political connections on firm value, Table 7 shows the estimation results when the analysis focuses on high-level politicians (model 23) and the impact of political directors is analyzed in terms of their classification as independent, significant shareholder representatives or executives (models 24, 25 and 26). With the exception of banks as dominant owners, in the remaining situations the results show that political connections have a positive and significant effect on firm value.

Political connections and firm value (sensitivity analysis).

| (23) | (24) | (25) | (26) | (27) | (28) | (29) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POLITICIANS_HIGH | 0.309***(17.20) | 0.178***(3.75) | 0.175***(6.08) | 0.272***(3.91) | |||

| FAMILY | 0.081**(2.14) | ||||||

| POLÍTICIANS_HIGH_Famy | 0.103***(2.86) | ||||||

| BANK | −0.215***(−2.64) | ||||||

| POLITICIANS_HIGH_Bank | −0.284***(−3.77) | ||||||

| PYRAMID | 0.025(0.28) | ||||||

| POLITICIANS_HIGH_Pyramid | 0.450***(5.14) | ||||||

| POLITICIANS_INDP | 0.057***(3.21) | ||||||

| POLITICIANS_DOMI | 0.200***(4.42) | ||||||

| POLITICIANS_EXC | 0.233***(3.06) | ||||||

| SIZE | −0.062 ***(−9.75) | −0.094***(−6.00) | −0.075***(−9.61) | −0.193***(−10.04) | −0.027***(−5.43) | −0.045***(−8.23) | 0.003(0.20) |

| DEBT | 0.291***(5.97) | 0.634***(8.74) | 0.371***(5.32) | 0.172***(11.95) | 0.300***(7.20) | 0.179***(3.63) | 0.290***(4.41) |

| MTB | 0.007***(13.47) | 0.001***(12.08) | 0.003***(11.29) | 0.019***(19.92) | 0.007***(13.64) | 0.008***(13.64) | 0.010***(3.35) |

| PRESI_DUAL | 0.149***(7.30) | 0.003***(0.1) | 0.240***(8.38) | 0.351***(5.33) | 0.150***(7.88) | 0.218***(12.58) | 0.142***(5.18) |

| Industry effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 1.038***(9.51) | 1.504***(6.56) | 1.359***(6.35) | 1.184***(5.85) | 0.792***(8.02) | 1.072***(9.26) | 21.970***(7.59) |

| F | 1013.70*** | 6931.56*** | 6835.39*** | 407.76*** | 3701.08*** | 2219.91*** | 338.82*** |

| M2 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 3.87 |

| Z1 | 143.65*** | 186.62*** | 49.38*** | 222.66*** | 67.97*** | 152.21*** | 15.17*** |

| Z2 | 102.31*** | 57.42*** | 178.77*** | 18.1*** | 113.95*** | 40.26*** | 74.53*** |

| Z3 | 412.07*** | 291.84*** | 192.93*** | 43.98*** | 676.04*** | 286.35*** | 153.15*** |

| Hansen test | 96.90 (103) | 96.53 (153) | 94.02 (119) | 60.58 (64) | 100.93 (103) | 91.14 (98) | 67.82 (71) |

Dependent variable: Q.TOBIN, is the ratio of the market value of the firm to the book value of its assets. POLITICIANS_HIGH, is a dummy variable that takes the value of one if at least one of the members of the board of directors has held a political position at the European or Spanish level in the past; otherwise, the value is zero. FAMILY and BANK are dummy variables that take the value of one if the dominant owner is a family or a bank, respectively; otherwise, the value is zero. PYRAMID, is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 when dominant owner control is exercised through a pyramidal structure; otherwise, the value is zero. POLITICIANS_HIGH_Famy, POLITICIANS_HIGH_Bank and POLITICIANS_HIGH_Pyramid are dummy variables that take the value of 1 if at least one of the board members has held a political position at the European or Spanish level in the past and the dominant owner is a family, a bank or control the firm through a pyramid, respectively; otherwise, the value is zero. POLITICIANS_INDP, POLITICIANS_DOMI and POLITICIANS_EXC are dummy variables that take the value of 1 if at least one of the board members has held a political position at the European, Spanish or local level in the past and this director is independent, significant shareholder representatives or executives, respectively; otherwise, the value is zero. SIZE, is the natural logarithm of the total assets. DEBT, is total debt divided by total assets. MTB, is the market value of equity divided by the book value of equity. PRESI_DUAL, is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the president of the board has an executive role and zero otherwise. Hansen, test of over-identifying restrictions, under the null hypothesis that all instruments are uncorrelated with the disturbance process. m2, statistic test for lack of second-order serial correlation in the first-difference residual. z1, Wald test of the joint significance of the reported coefficients. z2, Wald test of the joint significance of the industries dummies. z3, Wald test of the joint significance of the time dummies. In parentheses, t-statistics based on robust standard errors.

* Statistically significant at 1%.

In this paper, we have analyzed the relationship between dominant owners’ control and the presence of a politically connected board, as well as the impact of a politically connected board on firm value, in a sample of Spanish listed companies over the period 2003–2012. The results show that about half of the listed companies have a politically connected board. Furthermore, the results show that most of the political directors are independent, have an average tenure of six years and have an approximately 0.2% share in the company's voting rights. These results place Spain in between US and Asian companies. The studies of Agrawal and Knoeber (2001) and Goldman et al. (2009) show that 30% of US firms have politically connected boards, and Qian et al. (2011) and Firth et al. (2012) show that in China and Shangai, respectively, the percentage of politically connected firms is 80%.

Furthermore, the results show that voting rights and the family nature of the dominant owner have a negative impact on the probability of having a politician on the board. Thus, the results obtained reveal that political connections may determine the structure of corporate governance and, in particular, the composition of the board of directors. In this sense, the results are in line with those obtained by Yeh and Woidtke (2005), Durnev and Kim (2005), Kim et al. (2007) and Dahya et al. (2008) and show the importance of the dominant shareholder's ability to influence the composition of the board. Our study suggests that concentration of ownership and control stability facilitate the establishment of relationships and private channels between the dominant owner and political elites (Chen et al., 2011), which may reduce the need for a director with a “political role” because this role can be assumed by the dominant owner.

Additionally, the results show that family control's negative effect on the likelihood of having a politically connected board is independent of the voting rights of the dominant family. This result may reflect the importance of the qualitative aspects related to family control. Therefore, the family long-term commitment, the stability in control or the importance of the family reputation (Anderson and Reeb, 2003) seem to have a greater influence on board composition than the concentration of ownership in the hands of the controlling family. Thus, in line with the arguments of Morck (2009), the results seem to indicate that family control, regardless of ownership stake, has the social status and political influence necessary to obtain political rents without establishing explicit political connections on the board, thereby avoiding greater scrutiny (e.g., Riahi-Belkaoui, 2004; Chaney et al., 2011; Boubakri et al., 2012).

Regarding the impact of political connections on firm value, the results obtained show the presence of political directors to have a positive effect on firm value, irrespective of the political level of the director and the type of director (independent, significant shareholder representative or executive). Moreover, this positive effect is shown when we analyze the presence of political connections in family controlled firms and when the control is exercised through a pyramid structure. In this sense, the positive impact of political connections on firm value can reflect that political directors create value through their knowledge and influence on the development of laws that affect company performance or through the achievement of favours that benefit the company, and these advantages are expanded through pyramidal structures (e.g., Agrawal and Knoeber, 2001; Fisman, 2001; Faccio, 2006; Goldman et al., 2009; Boubakri et al., 2012; Duchin and Sosyura, 2012). Besides, the positive impact of political connections on firm value can be associated with such connections increasing social and media scrutiny and creating a growing concern for the reputation of the dominant owners and the political directors (e.g., Agrawal and Knoeber, 2001; Stafsudd, 2009). However, the results indicate that the presence of political directors in companies controlled by banks has a negative effect on firm value. This result may reflect behaviour contrary to firm value maximization when the company jointly incorporates the advantages of political connections with an eased access to bank financing and reduced discipline from the capital market (Qian et al., 2011).

Our study reveals a U-shaped reverse relationship (+/−) between tenure and firm value. That is, the firm value-tenure relationship has a tendency to grow until a certain point, at which the relationship becomes negative. This result may reflect that the advantages linked to the role of political directors that positively impact firm value will deteriorate over time, possibly resulting in the director losing power or influence in the political arena. In this sense, the estimation obtained indicates that the positive relationship holds during a 11-year tenure. Considering the average political director tenure in our sample (six years), we can conclude that most of the Spanish listed companies are on the positive end of the tenure-firm value relationship. Furthermore, the results indicate a nonlinear U-shaped effect (−/+) of ownership in the hands of political directors on firm value. This result shows that the effect of ownership in the hands of the political directors is negative up to a certain point, from which the relationship is positive. This result may reveal that the market expects that when a politician assumes lower costs of expropriation activities, he/she is more likely to perform these expropriation practices until his/her ownership stake reaches a certain threshold, at which point the market expects political directors to have greater incentives for adopting value-maximizing behaviour. Thus, the results obtained indicate a negative relationship until ownership stake reaches 6.3%, from which point the relationship begins to be positive. The average ownership stake for this type of board member is 0.2%, so we can conclude that the majority of Spanish listed companies are on the decreasing side of the relationship between voting in the hands of the political directors and firm value.

Our research provides evidence for regulators and economic agents of the need for greater transparency in the relationship between business “oligarchs” and political elites. In a context where the main role of the board of directors would be the protection of minority shareholders’ interests, the results obtained in this study point to the need for greater transparency about the role and professional profile of all directors, beyond the role of executives, significant shareholders’ representatives or independent directors.

This study does have some limitations, mainly related to the difficulty of measuring the existence of political connections. We focused on one type of political connection, but there may be other nexuses between political and business elites not captured in the current study; for example, those derived from family or corporate links.

Finally, this work opens up opportunities for future research on the analysis of the relationship between political connections and firm behaviour. Thus, the results indicate the need to further explore the relationship between political connections and family control or the incidence of political ties in corporate decisions.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments and suggestions received from the referees and from the Associate Editor, Susana Menéndez. We also thank the Research Agency of the Spanish Government for financial support (Project ECO2011-29144-CO3-02).

In this case we used the inclusion of the company in the Ibex-35 and the 12-month Euribor rate as instrumental variables, with both variables measured at the end of each of the years analyzed.

This is because although the coefficients are statistically significant, the value of these coefficients implies that the effect of the voting rights in the hands of the dominant family is zero. Therefore, the influence of family control on the likelihood of the presence of political connection on the board would be (if FAMILY=1): −0.054×VOTING−1.142×1+0.054×VOTING×1=−1.142+(−0.054+0.054)×VOTING=−1.142.