Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common sarcoma of soft tissues in childhood and adolescence, with an annual incidence of 4–7 cases per million children aged 15. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma is common in adults younger than 30 years, and are usually presented as a large painless, palpable mass (>5cm). Survival in the case of paratesticular sarcoma in men is approximately 50%.

Clinical caseMale 27 years of age with no history of importance, was seen in a clinic with an increased, painless, left testicular volume 3 years onset. Intrascrotal left testicle increased volume, with dimensions of 20cm×12cm×8cm, a stone and left inguinal node in induratum measuring 2cm×2cm. Microscopically, it showed a pattern of an embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma with left inguinal node metastases.

ConclusionEarly diagnosis of testicular tumours, and especially of primary intratesticular rhabdomyosarcomas, and aggressive surgical treatment in combination with chemotherapy reduces the incidence of local recurrence and may improve the rate of disease-free survival and overall survival in adult patients with metastases.

El rabdomiosarcoma es el sarcoma de tejidos blandos más común en la infancia y adolescencia, con incidencia anual de 4 a 7 casos por millón de niños de 15 años de edad. El rabdomiosarcoma embrionario es común en adultos menores de 30 años, y se presenta usualmente como una masa indolora, palpable grande (>5cm). La sobrevida en el caso de hombres con sarcoma paratesticular es aproximadamente del 50%.

Caso clínicoPaciente masculino de 27 años de edad, sin antecedentes de importancia. Acude a consulta por presentar 3 años con aumento de volumen testicular izquierdo, indoloro. A la exploración física del testículo izquierdo, es intraescrotal con aumentado de volumen, con dimensiones de 20×12×8cm, pétreo y con ganglio en región inguinal izquierda indurado de 2×2cm. Microscópicamente, con patrón de rabdomiosarcoma embrionario y ganglio inguinal izquierdo con metástasis de rabdomiosarcoma embrionario.

ConclusiónEl diagnóstico temprano de los tumores testiculares, y en especial de los rabdomiosarcomas intratesticulares primarios, así como el tratamiento quirúrgico agresivo en combinación con la quimioterapia disminuyen la incidencia de recurrencia local y podrían mejorar la tasa de supervivencia libre de enfermedad y la supervivencia global en pacientes adultos con metástasis.

Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common sarcoma of soft tissues in childhood and adolescence, with an annual incidence of 4–7 cases per million children aged 15.1 The aetiology of pure primary testicular rhabdomyosarcomas is unclear.2,3 They are extremely rare, with only 14 cases having been reported in the literature.3–8

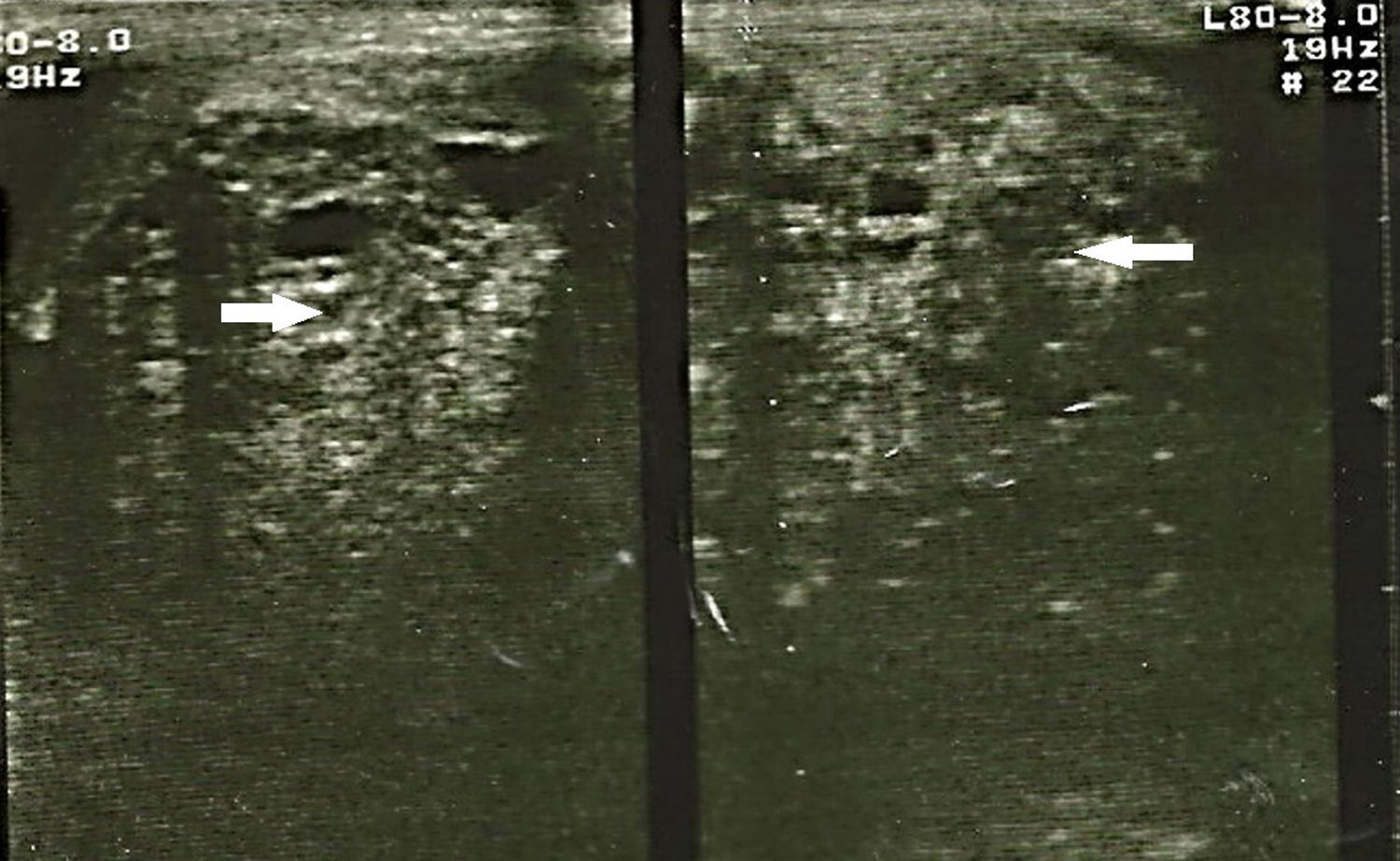

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma is common in adults under 30 years of age and usually present as a large painless, palpable mass (>5cm). Testicular ultrasound imaging shows a solid mass, although at times no distinction may be made between benign and malignant tumours.

The procedure of choice is an inguinal approach with a wide incision and high ligation of the spermatic cord and the testicle. Few publications exist to report on the results of testicular rhabdomyosarcoma treatment. Six cases of primary testicular rhabdomyosarcoma in adults were recently published in which aggressive surgical strategies and chemotherapy were used, resulting in a reduction in local recurrence and an improvement in the disease-free survival rate and overall survival rate in adult patients with metastases.8 There is an approximate survival rate of 50% in paratesticular sarcoma.2

The aim of this study is to present a clinical case study of primary testicular rhabdomyosarcoma in an adult, its aggression and management.

Clinical caseMale 27 years of age patient who presented at a clinic with an increased, painless, left testicular volume of 3 years onset. He also presented with a 6 month history of left hemi-abdominal pain, accompanied by nausea, immediately vomiting after meals and a weight loss of 12kg during the last 2 months. On physical examination the patient had a Karnofsky performance score of 50, the abdomen had increased in volume due to the tumour which had spread to the left hemi-abdomen, it was palpably painful and adherent to deep tissue. The intrascrotal right testicle measured 4cm×3cm×2cm, was of normal consistency, with normal spermatic cord; the intrascrotal left testicle had increased in volume, measured 20cm×12cm×8cm, contained a stone and uneven edges. It moved within the testicular sac, was not palpably painful and the spermatic cord was normal to the touch. A left inguinal node in induratum measuring 2cm×2cm was observed.

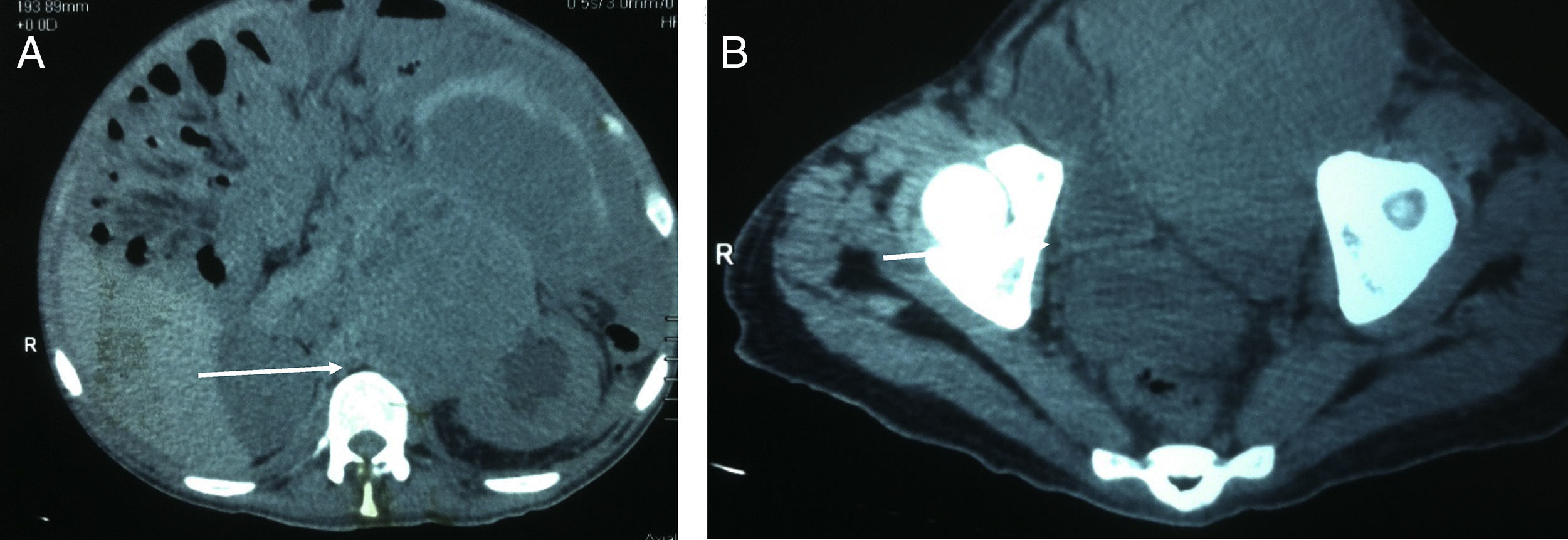

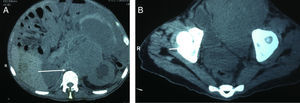

The study protocol for testicular tumours has pre-surgical alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) tumour markers of 1.39UI/ml, human chorionic gonadotrophin beta (GCH-b) of 3.7mUI/ml and lactate dehydrogenase of (DHL) 524UI/l. A chest X-ray revealed no images suggestive of lung metastases or metastases in the mediastinum. Testicular ultrasound imaging is shown in Fig. 1. Simple CAT scanning of the abdomen and pelvis showed a paraaeortic conglomerated node which spread from the inferior mesenteric artery to the pelvic cavity, which led to severe pyelocaliceal ectasia of the left kidney (Fig. 2).

On 4th December 2014 a double j left stent was inserted and left radical orchiectomy was performed. During surgery we observed a left testicular tumour of 18cm×11cm×8cm, of grainy consistency, with no invasion of the scrotum, with congested spermatic cord, and inguinal node induratum of 2cm×3cm.

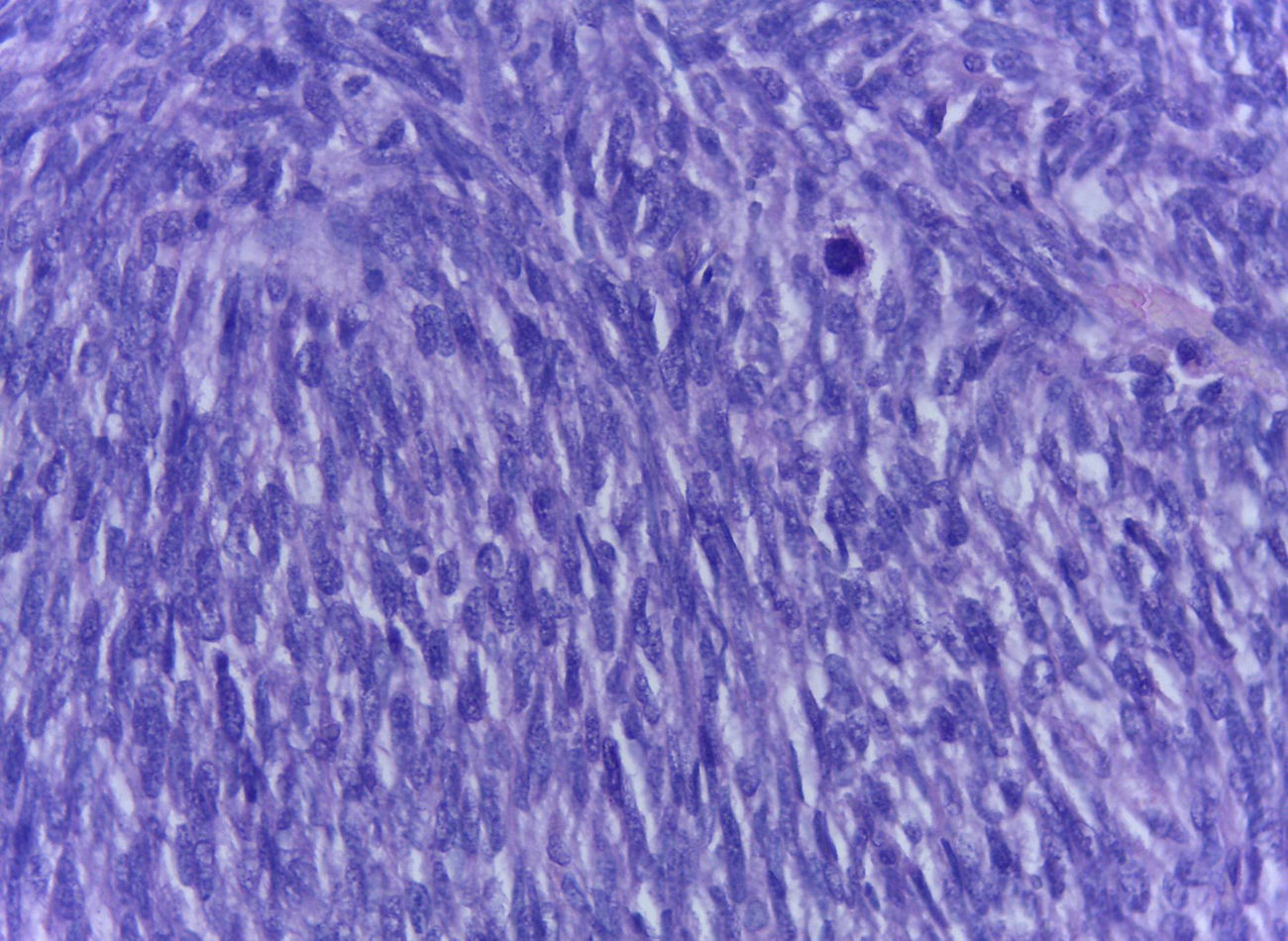

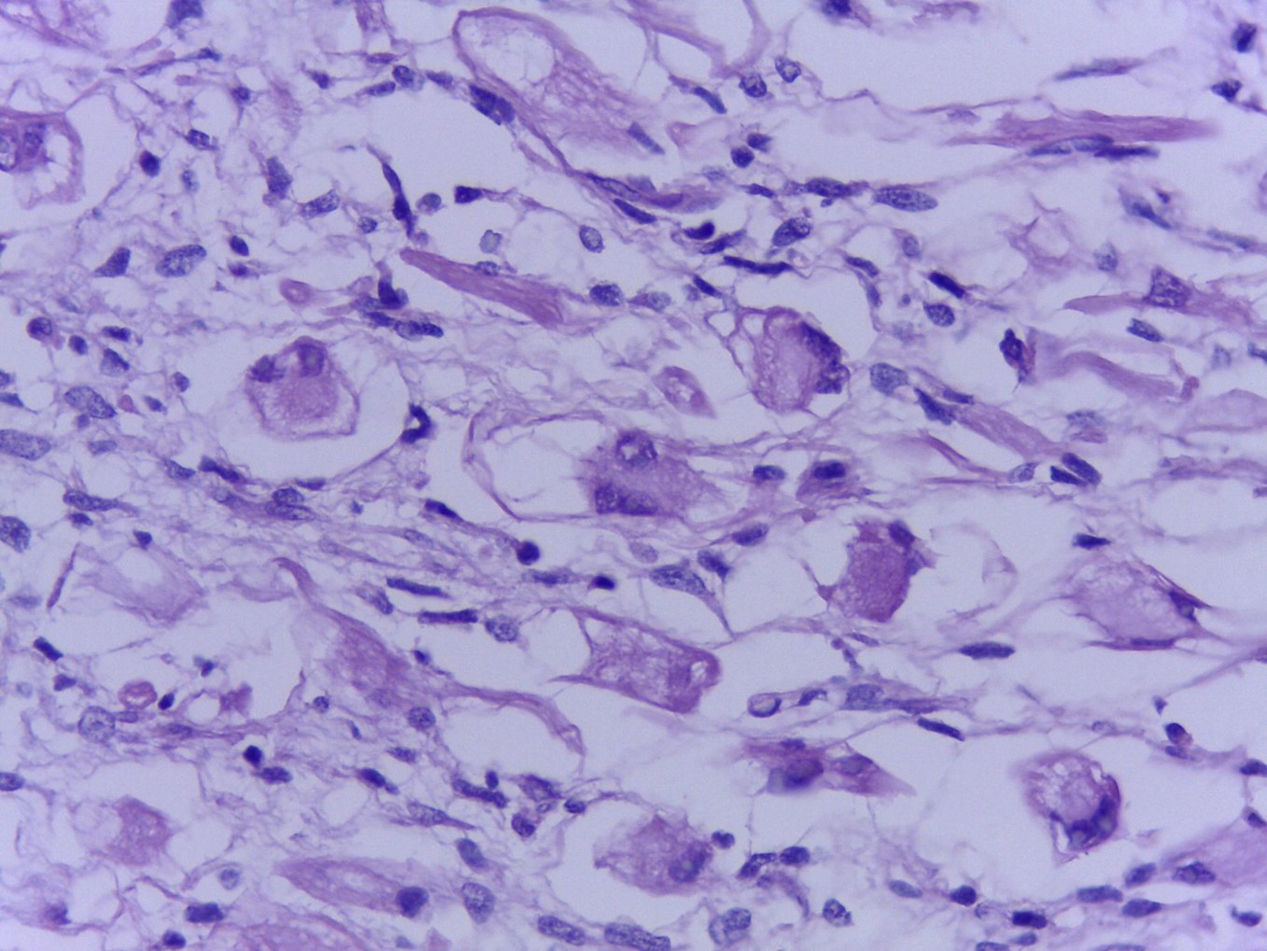

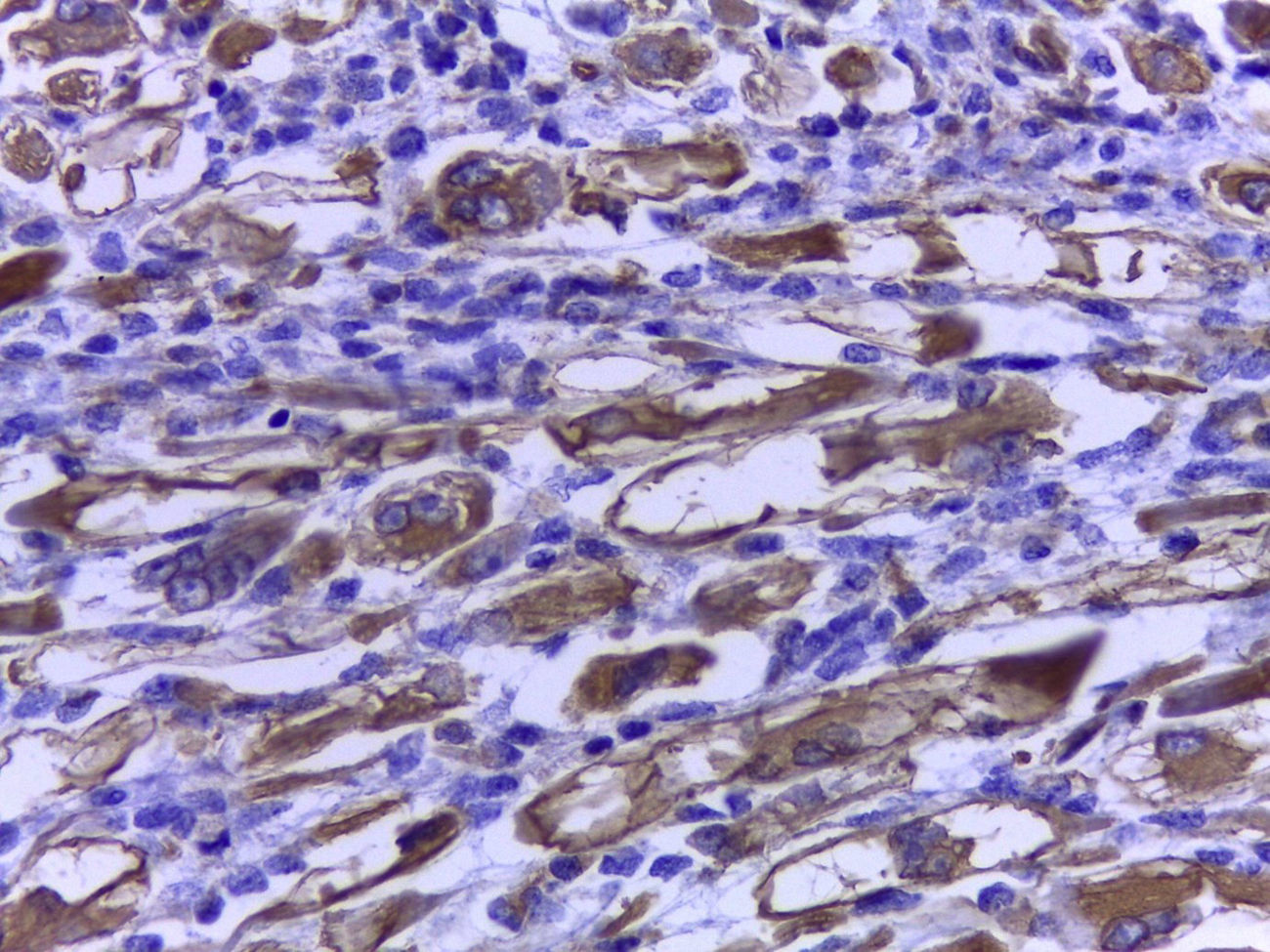

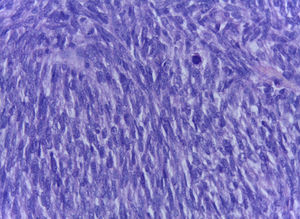

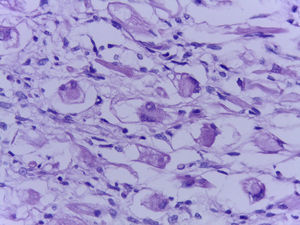

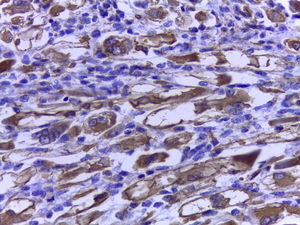

The official histopathological report stated that there was macroscopic evidence of a surgical specimen measuring 17.5cm×11cm, coffee-coloured, with a neoplasic type whitish-grey 13cm tumour inside it, h necrotic areas, and a 9cm congested spermatic cord. Left inguinal node was 5.5cm, grey in colour, with a neoplasic appearance. Microscopically, it showed a pattern of an embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma measuring 13cm, with left inguinal node metastases (Figs. 3–5).

The tumour markers 7 days after radical left orchietrocmy showed an AFP of 1.04UI/ml, (GCH-b) of 3.93mUI/ml and DHL of 497UI/l. Other requested studies showed haemoglobin of 10.2g/dl, 31.3% haematocrits, glucose of 90mg/dl, urea of 91mg/dl, creatinine of 3.9mg/dl, and a creatinine clearance test in urine over 24h of 59ml/min.

The patient's tumour was staged as pT2 N3 M0, clinical stage IIIC, and as a result chemotherapy based on Ifosfamide and Epirubicin was offered. However, the patient died 2 weeks after surgery, prior to the first cycle of chemotherapy, due to patient withdrawal from treatment.

DiscussionPrimary intratesticular rhabdomyosarcomas are extremely rare and aggressive, and only 20 cases have been reported in the literature to date.1–9

Primary intratesticular rhabdomyosarcomas present as a painless intrascrotal mass in adult patients. Serum levels of AFP, GCH-b and DHL are normal on occasion. Macroscopic, microscopic and immunohistochemical studies are the gold standard for rhabdomyosarcoma diagnosis and distinguish intratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma from paratesticular or spermatic spinal rhabdomyosarcoma.1,6,9

At diagnosis rhabdomyosarcomas often present with node compromise or metastasis. Multidisciplinary treatment may improve the prognosis of this disease.10

Histologically, several types may be identified: the embryonal, the botryoidal (variation of embryonal), the alveolar (with its solid variant), the pleomorphic and subtypes such as fusocellular and sclerosing pseudovascular. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma is the most aggressive type; it progresses rapidly and frequently presents with early metastases, leading to raised mortality compared with embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma.11–14

Immunohistochemistry is a powerful tool for identifying the cancer cell lines of all these tumours. Anti desmin, actin and myoglobin antibodies have been used as muscular markers. Myoglobin is a more sensitive marker, and only presents in differentiated rhabdomyoblasts. However, it must be considered that myoglobin may frequently test negative in poorly differentiated rhabdomyosarcomas. The sarcomeric actin is only present in well differentiated rhabdomyoblasts and has occasionally been described in leiomyosarcomas. Myogenin and MyoD1, which recognize nuclear proteins of the transcription factor family, are sensitive and specific for rhabdomyosarcomas.12,13

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma may present in 2 translocations: t (2;13) in over 50% of cases and t (1;13) in 22%. These translocations are not present in other types of rhabdomyosarcoma.11

Radical orchiectomy is obligatory for all patients, meeting the requirements of complete resection of the primary tumour. There is greater probability of retroperitoneal disease in adults in testicular cancer, and as a result retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy is recommended in these cases. It is necessary in the case of adults, even those with disease-free lymph nodes showing up in pre-operative imaging studies.15

Chemotherapy is generally effective in this type of sarcoma and currently vincristine, actinomycin-D and cyclophosphamide (VAC) and isophosphamide, vincristine and actinomycin-D regimens continue to be the basis of treatment for rhabdomyosarcomas16; however, if these regimens are applied to the adult patient, a high dose of vincristine (maximum dose 2mg/body) should be administered and thus, in general, the vincristine dose is relatively reduced (low relative dose intensity). As a result, the effect of chemotherapy is affected in adult patients with rhabdomyosarcoma and prognosis in these patients is extremely poor. Surgery for metastatic tumours may be effective in selected patients. For those patients whose tumours were initially considered unresectable, a secondary procedure should be considered following initial chemotherapy.8,15

In adults, rhabdomyosarcomas of the bladder and prostate, adjuvant radiotherapy is not considered necessary when the patient has had a complete surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy.17,18

Radiotherapy is more frequently recommended to control the local recurrence of rhabdomyosarcomas or for unfavourable histological results, such as alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma.19,20

ConclusionsPrimary intratesticular rhabdomyosarcomas are rare, with only 20 cases having been reported in the literature worldwide. As a result little knowledge exists on this type of tumour. It has been reported in recent series that early diagnosis of testicular tumours, and particularly of primary intratesticular rhabdomyosarcomas, in addition to aggressive surgical treatment in combination with chemotherapy reduces the incidence of local recurrence and may improve the disease-free survival rate and overall survival rate in adult patients with metastases.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consent.The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Mejía-Salas JA, Sánchez-Corona H, Priego-Niño A, Cárdenas-Rodríguez E, Sánchez-Galindo JA. Rabdomiosarcoma testicular primario: reporte de un caso. Cir Cir. 2017;85:143–147.