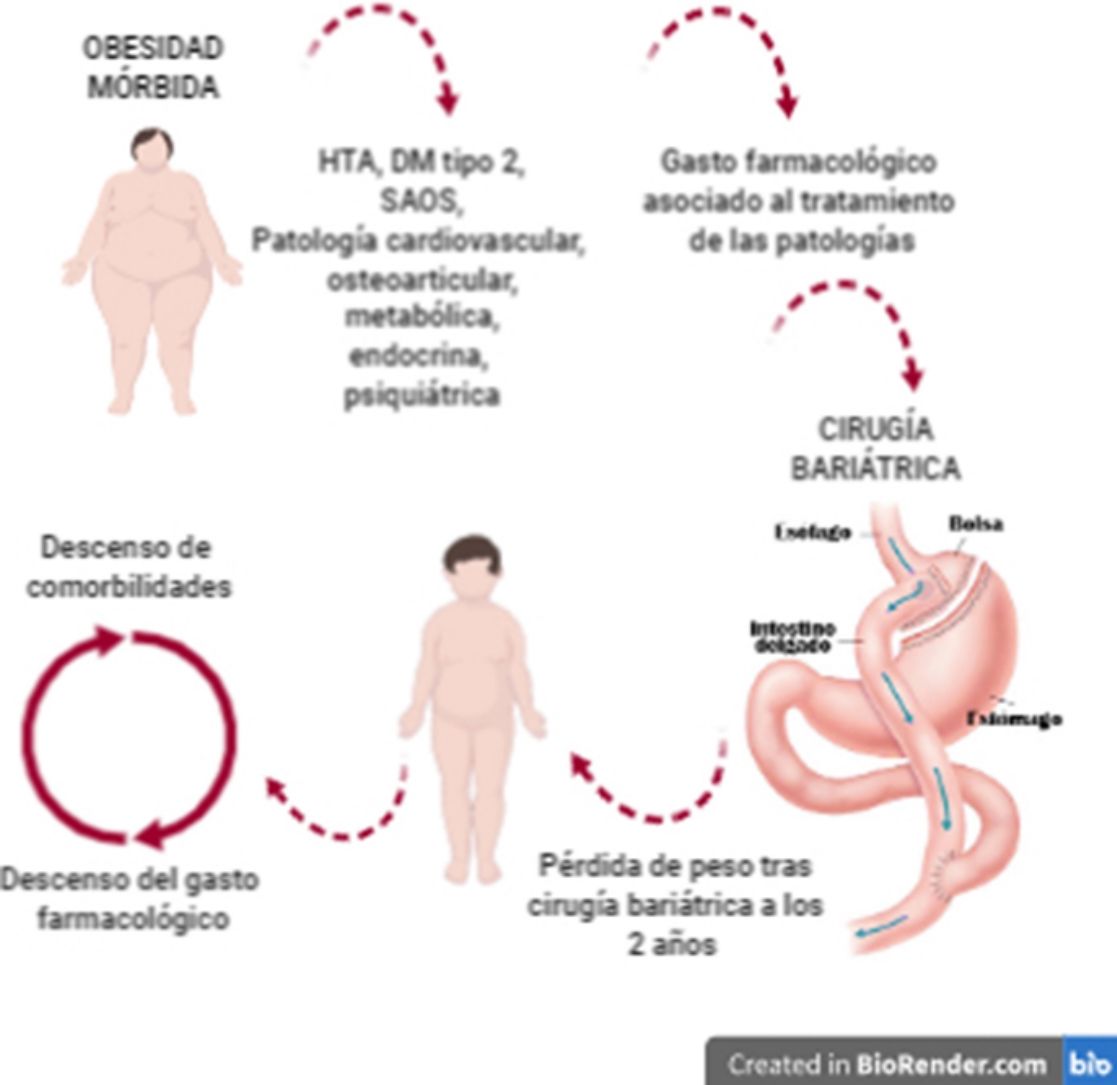

Obesity and associated diseases represent an important health and economic problem since pharmacological treatment for many of these pathologies needs lifelong subsidies. Theoretically, bariatric and metabolic surgery decreases the medication requirements of patients for these diseases but may result in other types of pharmacological needs. This study aims to demonstrate whether there is a real decrease in pharmacological expenditure after bariatric surgery.

Material and methodsRetrospective cross-sectional analysis of patients who were treated in our centre between 2012 and 2016, comparing different associated comorbidities and pharmacological expenses one month before and 2 years after surgery.

Results400 patients were operated. The results were presented, showing the differences between the resolution of the different comorbidities and the pharmacological savings generated for each of the surgical techniques studied. The most cost-effective comorbidity in the study was type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2). The surgical technique with the best results was metabolic bypass, presenting a cost difference after surgery of 507 euros per month (P < 0.001).

ConclusionsIn a 2-year follow-up after bariatric surgery, a decreased prevalence of obesity-related diseases and associated pharmacological expenditure was observed, showing the efficiency of this intervention over the medium term.

La obesidad y las enfermedades asociadas a ella suponen un importante problema, y no solo sanitario, sino también económico, ya que muchas de esas patologías son subsidiarias de tratamiento farmacológico de por vida. La cirugía bariátrica y metabólica, a priori, disminuye la demanda de medicamentos de estos pacientes, pero puede condicionar otro tipo de necesidades farmacológicas. El objetivo del estudio es demostrar si existe un descenso real del gasto farmacológico tras la cirugía bariátrica.

Material y métodosAnálisis retrospectivo transversal de los pacientes intervenidos en nuestro centro entre 2012 y 2016, comparando las distintas comorbilidades y los gastos farmacológicos asociados a ellas un mes antes y a los 2 años de la cirugía.

ResultadosFueron intervenidos 400 pacientes. Se presentaron los resultados mostrando para cada una de las técnicas quirúrgicas estudiadas las diferencias entre la resolución de las distintas comorbilidades y el ahorro farmacológico generado. La comorbilidad más coste-efectiva del estudio fue la diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2). La técnica quirúrgica con mejores resultados fue el bypass metabólico, presentando una diferencia de costes tras la cirugía de 507 euros mensuales (p < 0,001).

ConclusionesEn un seguimiento de 2 años tras la cirugía bariátrica se produce un descenso en la prevalencia de las enfermedades asociadas a la obesidad y del gasto farmacológico asociado a ellas, lo que demuestra que este tipo de intervención resulta eficiente a medio plazo.

In the most developed and developing countries, obesity is a serious health problem, not only by itself, but also due to associated pathologies. Obesity is currently considered a global pandemic.1,2

In the long term, bariatric surgery leads to a decrease in body weight and an improvement of the diseases associated with obesity, which are resolved in many cases.3

These pathologies usually require pharmacological treatments to be controlled, generating a pharmacological need that is usually life-long if the obesity is not resolved or improved. This entails significant costs for healthcare systems and for patients themselves.4

The objective of this study is to analyze the pharmacological needs of patients treated surgically for morbid obesity, comparing the time before surgery and after a 2-year follow-up to assess whether there is a decrease in these needs and, consequently, a decrease in pharmacological costs.

MethodsWe designed a retrospective cross-sectional study that included 400 patients who underwent bariatric surgery between January 2012 and November 2016.

Demographic and clinical variables were studied one month prior to surgery, including age, sex, weight, height and body mass index (BMI), as well as comorbidities associated with morbid obesity, taking into account that their existence always implied pharmacological treatment: hypertension (HTN); type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM); obstructive sleep apnea (OSA); cardiovascular, osteoarticular, endocrine, metabolic, and psychiatric pathologies; and other comorbidities related with morbid obesity (hyperuricemia, vitamin and nutritional deficiencies, hiatal hernia).

Pharmacological costs were calculated in euros for each patient during a period of 30 days, one month prior to surgery and 2 years post-op. To collect the data on the medication administered, we used the Valencian healthcare administration computer system (Agencia Valenciana de Salud, Abucasis® system), taking into account the frequency of administration of the drug or the IU/mL injected each day per patient in the case of insulin. The prices of the drugs were obtained from the Vademecum® International from 2011. OSA was not included as a comorbidity that implied an associated pharmacological expense, as it is only related with the use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).

The following surgical factors were considered: anesthetic ASA, bariatric surgery performed, postoperative complications, need for reoperation, days of hospital stay and presence of sequelae, defined as the pathology produced as a direct consequence of bariatric surgery (cholelithiasis, incisional hernia, internal hernia, etc).

Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) was initially indicated in patients with BMI > 50 kg/m2 as the first stage to facilitate a second stage with a mixed technique. Because of the good results, its indications were subsequently extended to include: BMI 35–40 with major comorbidities; age >60 years; high-risk patients with liver disease, severe heart disease, or chronic kidney failure; and patients with gastric pathology, especially premalignant types.

Gastric bypass was indicated in patients with BMI < 50 and in cases of metabolic alterations. In diabetic patients, a different bypass was created (metabolic bypass) to try to improve the metabolic component, extending the length of the biliopancreatic limb according to the proximal intestine theory. Likewise, the eating habits of the patients were determined, and bypass was chosen in patients with a tendency to peck and those with a sweet tooth, in whom it was also the first choice due to the high failure rate of restrictive techniques.

The outcome variables collected 2 years after surgery were: weight/BMI and persistence; and re-appearance or resolution of the aforementioned comorbidities. By design, the improvement of the pathologies was not considered in this study since the existence of a pharmacological treatment is what defines its prevalence, even though the amount of drugs used for its management had been reduced.

The patients included in the study had undergone bariatric surgery, including SG, conventional bypass (biliopancreatic limb 60 cm and digestive limb 150−200 cm) and metabolic bypass (biliopancreatic limb 100 cm and digestive limb 150−200 cm), with ages between 18 and 60 years, in accordance with the established indications. All techniques were performed laparoscopically. Patients treated with gastric band removal and other revision surgeries were excluded from the study.

Continuous variables were presented as median (interquartile range) and qualitative variables as frequencies (percentages). As statistical tests of inference, the MacNemar test was used for qualitative measures. For quantitative measures, the Mann-Whitney tests were used for the comparison of two independent means, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for two related means. For comparisons of more than two independent means, the ANOVA test or the Kruskal-Wallis test was used, depending on the type of variable. The cost-effectiveness analysis was performed with the heabs and heapbs commands of the STATA program. For the statistical analysis, the SPSS® version 20 software package (IBM, Armonk, New York, United States) and the STATA version 15 statistical package were used. In all cases, a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

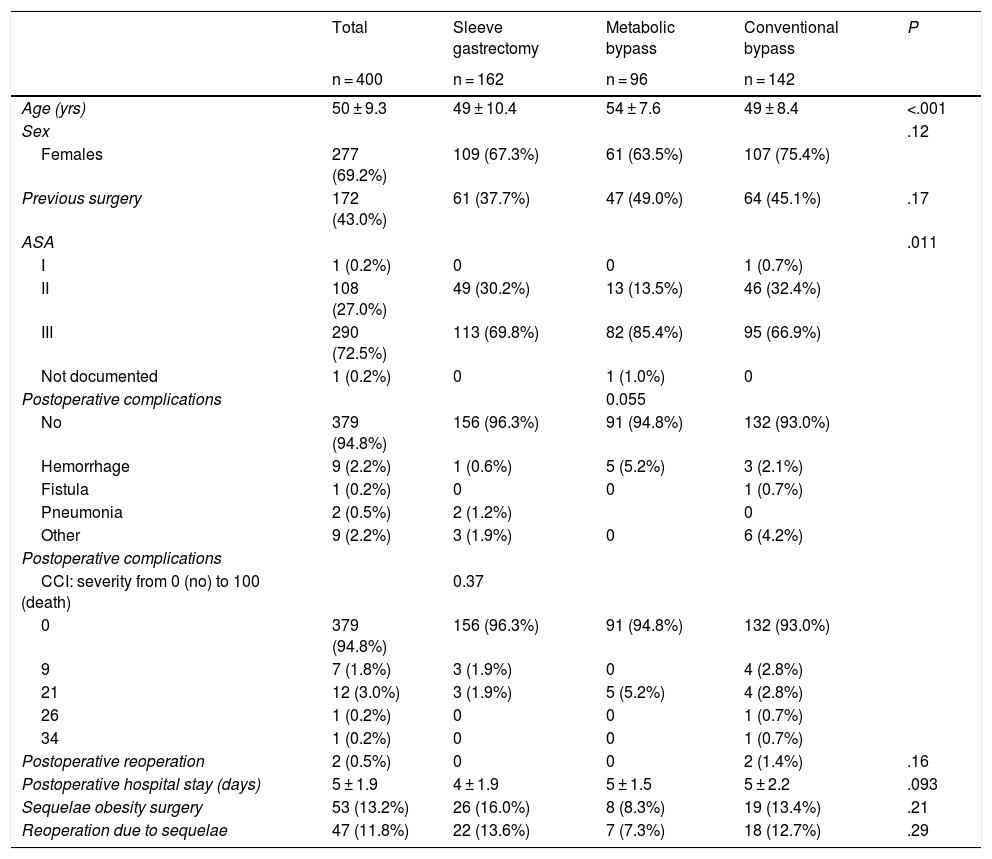

ResultsThe mean age of the surgically treated patients was 50 years, with a predominance of females. Complications were rare and mostly entailed bleeding from the suture. Only two patients required reoperation, and the mean hospital stay was 5 days. Sequelae were observed in 13.2% of the patients and required surgical intervention in 11.8% of cases (Table 1).

Demographic and surgical treatment characteristics.

| Total | Sleeve gastrectomy | Metabolic bypass | Conventional bypass | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 400 | n = 162 | n = 96 | n = 142 | ||

| Age (yrs) | 50 ± 9.3 | 49 ± 10.4 | 54 ± 7.6 | 49 ± 8.4 | <.001 |

| Sex | .12 | ||||

| Females | 277 (69.2%) | 109 (67.3%) | 61 (63.5%) | 107 (75.4%) | |

| Previous surgery | 172 (43.0%) | 61 (37.7%) | 47 (49.0%) | 64 (45.1%) | .17 |

| ASA | .011 | ||||

| I | 1 (0.2%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.7%) | |

| II | 108 (27.0%) | 49 (30.2%) | 13 (13.5%) | 46 (32.4%) | |

| III | 290 (72.5%) | 113 (69.8%) | 82 (85.4%) | 95 (66.9%) | |

| Not documented | 1 (0.2%) | 0 | 1 (1.0%) | 0 | |

| Postoperative complications | 0.055 | ||||

| No | 379 (94.8%) | 156 (96.3%) | 91 (94.8%) | 132 (93.0%) | |

| Hemorrhage | 9 (2.2%) | 1 (0.6%) | 5 (5.2%) | 3 (2.1%) | |

| Fistula | 1 (0.2%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Pneumonia | 2 (0.5%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0 | ||

| Other | 9 (2.2%) | 3 (1.9%) | 0 | 6 (4.2%) | |

| Postoperative complications | |||||

| CCI: severity from 0 (no) to 100 (death) | 0.37 | ||||

| 0 | 379 (94.8%) | 156 (96.3%) | 91 (94.8%) | 132 (93.0%) | |

| 9 | 7 (1.8%) | 3 (1.9%) | 0 | 4 (2.8%) | |

| 21 | 12 (3.0%) | 3 (1.9%) | 5 (5.2%) | 4 (2.8%) | |

| 26 | 1 (0.2%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.7%) | |

| 34 | 1 (0.2%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Postoperative reoperation | 2 (0.5%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.4%) | .16 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (days) | 5 ± 1.9 | 4 ± 1.9 | 5 ± 1.5 | 5 ± 2.2 | .093 |

| Sequelae obesity surgery | 53 (13.2%) | 26 (16.0%) | 8 (8.3%) | 19 (13.4%) | .21 |

| Reoperation due to sequelae | 47 (11.8%) | 22 (13.6%) | 7 (7.3%) | 18 (12.7%) | .29 |

CCI: Comprehensive Classification Index.

Mean ± standard deviation for continuous measures, and frequency (%) for categorical measures.

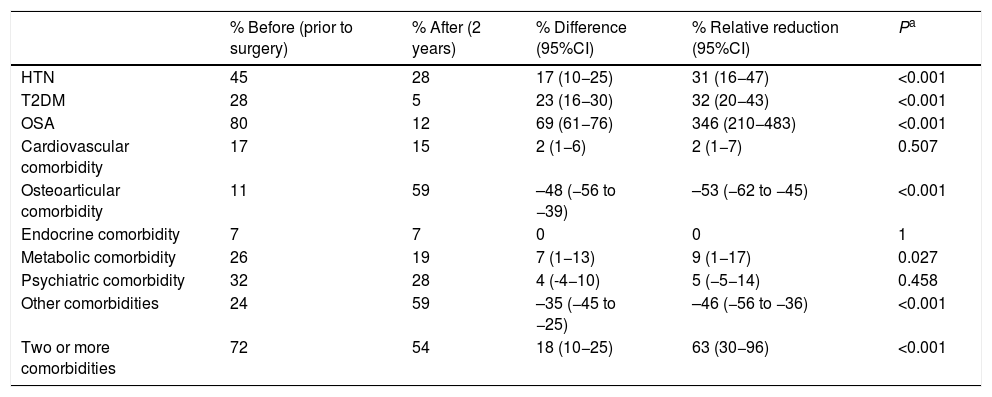

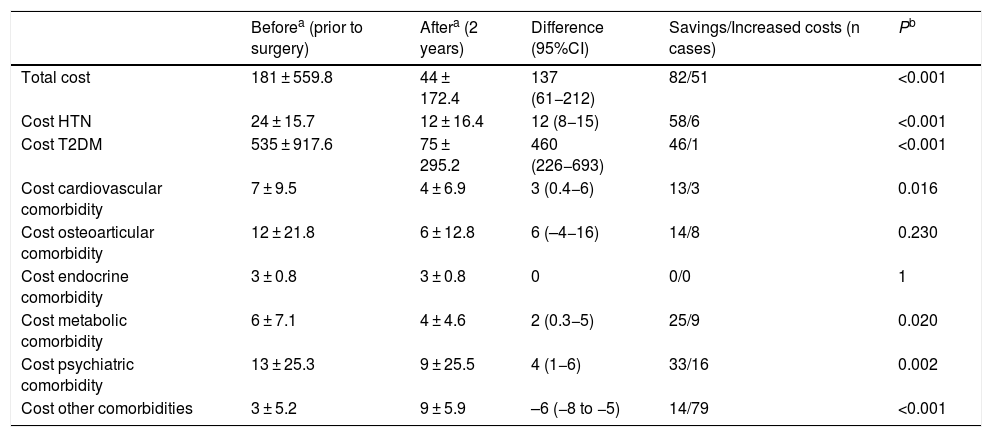

When we analyzed the changes in the different comorbidities in the SG group (Table 2), the best results (resolution) were obtained for OSA, T2DM and HTN. In terms of costs (Table 3), there was a savings in general terms, especially for T2DM and hypertension.

Sleeve gastrectomy (n = 162); comorbidities.

| % Before (prior to surgery) | % After (2 years) | % Difference (95%CI) | % Relative reduction (95%CI) | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTN | 45 | 28 | 17 (10−25) | 31 (16−47) | <0.001 |

| T2DM | 28 | 5 | 23 (16−30) | 32 (20−43) | <0.001 |

| OSA | 80 | 12 | 69 (61−76) | 346 (210−483) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity | 17 | 15 | 2 (1−6) | 2 (1−7) | 0.507 |

| Osteoarticular comorbidity | 11 | 59 | –48 (−56 to −39) | –53 (−62 to −45) | <0.001 |

| Endocrine comorbidity | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Metabolic comorbidity | 26 | 19 | 7 (1−13) | 9 (1−17) | 0.027 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | 32 | 28 | 4 (-4−10) | 5 (−5−14) | 0.458 |

| Other comorbidities | 24 | 59 | –35 (−45 to −25) | –46 (−56 to −36) | <0.001 |

| Two or more comorbidities | 72 | 54 | 18 (10−25) | 63 (30−96) | <0.001 |

T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension; CI: confidence interval; OSA: obstructive sleep apnea.

Sleeve gastrectomy (n = 162); costs (€).

| Beforea (prior to surgery) | Aftera (2 years) | Difference (95%CI) | Savings/Increased costs (n cases) | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost | 181 ± 559.8 | 44 ± 172.4 | 137 (61−212) | 82/51 | <0.001 |

| Cost HTN | 24 ± 15.7 | 12 ± 16.4 | 12 (8−15) | 58/6 | <0.001 |

| Cost T2DM | 535 ± 917.6 | 75 ± 295.2 | 460 (226−693) | 46/1 | <0.001 |

| Cost cardiovascular comorbidity | 7 ± 9.5 | 4 ± 6.9 | 3 (0.4−6) | 13/3 | 0.016 |

| Cost osteoarticular comorbidity | 12 ± 21.8 | 6 ± 12.8 | 6 (–4−16) | 14/8 | 0.230 |

| Cost endocrine comorbidity | 3 ± 0.8 | 3 ± 0.8 | 0 | 0/0 | 1 |

| Cost metabolic comorbidity | 6 ± 7.1 | 4 ± 4.6 | 2 (0.3−5) | 25/9 | 0.020 |

| Cost psychiatric comorbidity | 13 ± 25.3 | 9 ± 25.5 | 4 (1−6) | 33/16 | 0.002 |

| Cost other comorbidities | 3 ± 5.2 | 9 ± 5.9 | –6 (−8 to −5) | 14/79 | <0.001 |

T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension; CI: confidence interval.

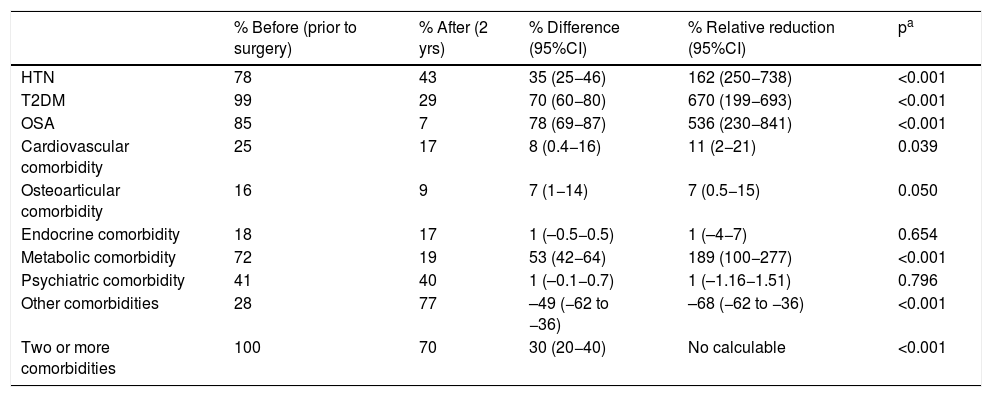

As for metabolic bypass, OSA, T2DM, HTN and metabolic pathology obtained the highest resolution 2 years after surgery (Table 4). The total savings presented by this technique were excellent, especially associated with the decrease in costs in the T2DM group (Table 5).

Metabolic bypass (n = 96); comorbidities.

| % Before (prior to surgery) | % After (2 yrs) | % Difference (95%CI) | % Relative reduction (95%CI) | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTN | 78 | 43 | 35 (25−46) | 162 (250−738) | <0.001 |

| T2DM | 99 | 29 | 70 (60−80) | 670 (199−693) | <0.001 |

| OSA | 85 | 7 | 78 (69−87) | 536 (230−841) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity | 25 | 17 | 8 (0.4−16) | 11 (2−21) | 0.039 |

| Osteoarticular comorbidity | 16 | 9 | 7 (1−14) | 7 (0.5−15) | 0.050 |

| Endocrine comorbidity | 18 | 17 | 1 (–0.5−0.5) | 1 (–4−7) | 0.654 |

| Metabolic comorbidity | 72 | 19 | 53 (42−64) | 189 (100−277) | <0.001 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | 41 | 40 | 1 (–0.1−0.7) | 1 (–1.16−1.51) | 0.796 |

| Other comorbidities | 28 | 77 | –49 (−62 to −36) | –68 (−62 to −36) | <0.001 |

| Two or more comorbidities | 100 | 70 | 30 (20−40) | No calculable | <0.001 |

T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension; CI: confidence interval; OSA: obstructive sleep apnea.

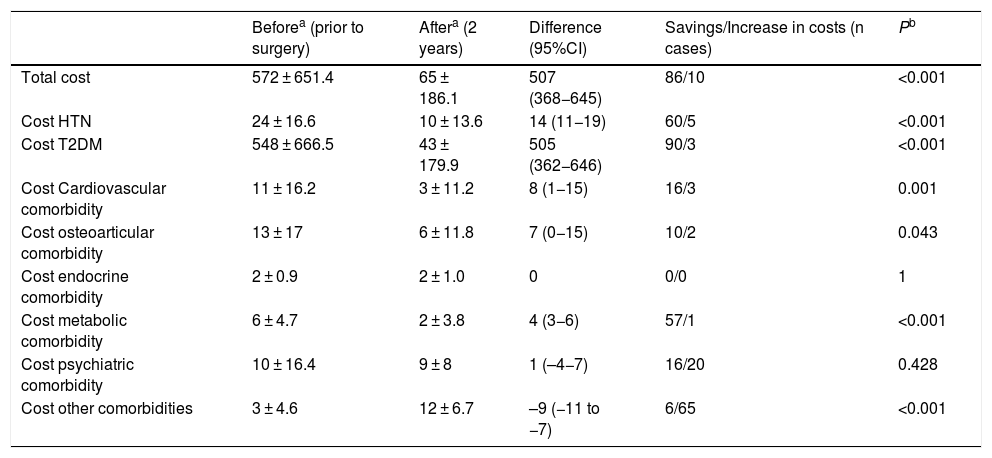

Metabolic bypass (n = 96); costs (€).

| Beforea (prior to surgery) | Aftera (2 years) | Difference (95%CI) | Savings/Increase in costs (n cases) | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost | 572 ± 651.4 | 65 ± 186.1 | 507 (368−645) | 86/10 | <0.001 |

| Cost HTN | 24 ± 16.6 | 10 ± 13.6 | 14 (11−19) | 60/5 | <0.001 |

| Cost T2DM | 548 ± 666.5 | 43 ± 179.9 | 505 (362−646) | 90/3 | <0.001 |

| Cost Cardiovascular comorbidity | 11 ± 16.2 | 3 ± 11.2 | 8 (1−15) | 16/3 | 0.001 |

| Cost osteoarticular comorbidity | 13 ± 17 | 6 ± 11.8 | 7 (0−15) | 10/2 | 0.043 |

| Cost endocrine comorbidity | 2 ± 0.9 | 2 ± 1.0 | 0 | 0/0 | 1 |

| Cost metabolic comorbidity | 6 ± 4.7 | 2 ± 3.8 | 4 (3−6) | 57/1 | <0.001 |

| Cost psychiatric comorbidity | 10 ± 16.4 | 9 ± 8 | 1 (–4−7) | 16/20 | 0.428 |

| Cost other comorbidities | 3 ± 4.6 | 12 ± 6.7 | –9 (−11 to −7) | 6/65 | <0.001 |

T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension; CI: confidence interval.

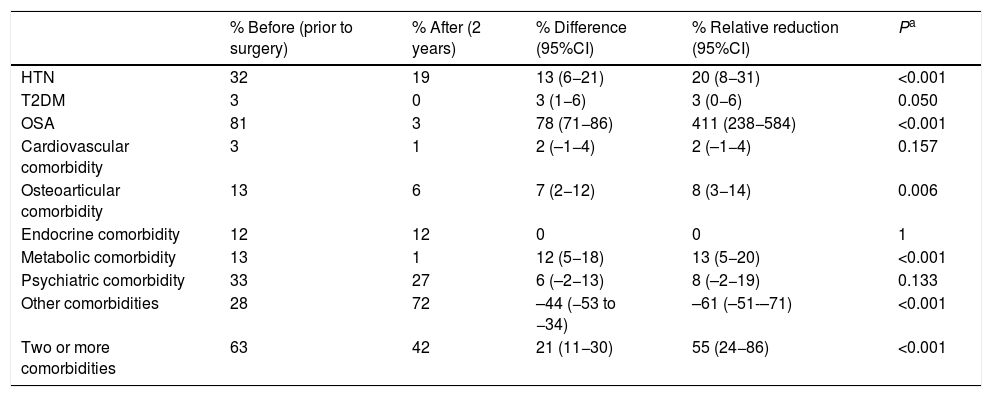

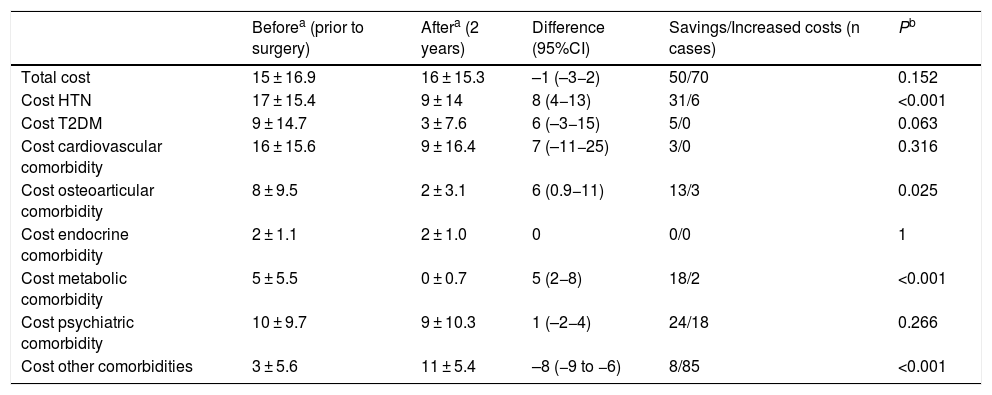

Regarding conventional bypass, the comorbidities with the best results were OSA, HTN and metabolic pathology (Table 6). In terms of expenses, this was the only technique that showed an increase in total costs (Table 7).

Conventional bypass (n = 142); comorbidities.

| % Before (prior to surgery) | % After (2 years) | % Difference (95%CI) | % Relative reduction (95%CI) | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTN | 32 | 19 | 13 (6−21) | 20 (8−31) | <0.001 |

| T2DM | 3 | 0 | 3 (1−6) | 3 (0−6) | 0.050 |

| OSA | 81 | 3 | 78 (71−86) | 411 (238−584) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity | 3 | 1 | 2 (–1−4) | 2 (–1−4) | 0.157 |

| Osteoarticular comorbidity | 13 | 6 | 7 (2−12) | 8 (3−14) | 0.006 |

| Endocrine comorbidity | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Metabolic comorbidity | 13 | 1 | 12 (5−18) | 13 (5−20) | <0.001 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | 33 | 27 | 6 (–2−13) | 8 (–2−19) | 0.133 |

| Other comorbidities | 28 | 72 | –44 (−53 to −34) | –61 (–51-–71) | <0.001 |

| Two or more comorbidities | 63 | 42 | 21 (11−30) | 55 (24−86) | <0.001 |

T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension; CI: confidence interval; OSA: obstructive sleep apnea.

Conventional bypass (n = 142); costs (€).

| Beforea (prior to surgery) | Aftera (2 years) | Difference (95%CI) | Savings/Increased costs (n cases) | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost | 15 ± 16.9 | 16 ± 15.3 | –1 (–3−2) | 50/70 | 0.152 |

| Cost HTN | 17 ± 15.4 | 9 ± 14 | 8 (4−13) | 31/6 | <0.001 |

| Cost T2DM | 9 ± 14.7 | 3 ± 7.6 | 6 (–3−15) | 5/0 | 0.063 |

| Cost cardiovascular comorbidity | 16 ± 15.6 | 9 ± 16.4 | 7 (–11−25) | 3/0 | 0.316 |

| Cost osteoarticular comorbidity | 8 ± 9.5 | 2 ± 3.1 | 6 (0.9−11) | 13/3 | 0.025 |

| Cost endocrine comorbidity | 2 ± 1.1 | 2 ± 1.0 | 0 | 0/0 | 1 |

| Cost metabolic comorbidity | 5 ± 5.5 | 0 ± 0.7 | 5 (2−8) | 18/2 | <0.001 |

| Cost psychiatric comorbidity | 10 ± 9.7 | 9 ± 10.3 | 1 (–2−4) | 24/18 | 0.266 |

| Cost other comorbidities | 3 ± 5.6 | 11 ± 5.4 | –8 (−9 to −6) | 8/85 | <0.001 |

T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension; CI: confidence interval.

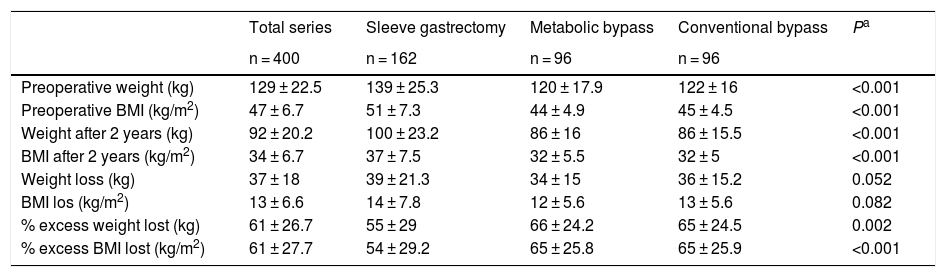

Table 8 analyzes the changes in weight values by surgical technique. The values of the three groups were within the quality indicators of weight loss established for bariatric surgery, although the two bypass techniques were higher.

Weight values according to surgical technique.

| Total series | Sleeve gastrectomy | Metabolic bypass | Conventional bypass | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 400 | n = 162 | n = 96 | n = 96 | ||

| Preoperative weight (kg) | 129 ± 22.5 | 139 ± 25.3 | 120 ± 17.9 | 122 ± 16 | <0.001 |

| Preoperative BMI (kg/m2) | 47 ± 6.7 | 51 ± 7.3 | 44 ± 4.9 | 45 ± 4.5 | <0.001 |

| Weight after 2 years (kg) | 92 ± 20.2 | 100 ± 23.2 | 86 ± 16 | 86 ± 15.5 | <0.001 |

| BMI after 2 years (kg/m2) | 34 ± 6.7 | 37 ± 7.5 | 32 ± 5.5 | 32 ± 5 | <0.001 |

| Weight loss (kg) | 37 ± 18 | 39 ± 21.3 | 34 ± 15 | 36 ± 15.2 | 0.052 |

| BMI los (kg/m2) | 13 ± 6.6 | 14 ± 7.8 | 12 ± 5.6 | 13 ± 5.6 | 0.082 |

| % excess weight lost (kg) | 61 ± 26.7 | 55 ± 29 | 66 ± 24.2 | 65 ± 24.5 | 0.002 |

| % excess BMI lost (kg/m2) | 61 ± 27.7 | 54 ± 29.2 | 65 ± 25.8 | 65 ± 25.9 | <0.001 |

BMI: body mass index.

Values in mean ± standard deviation.

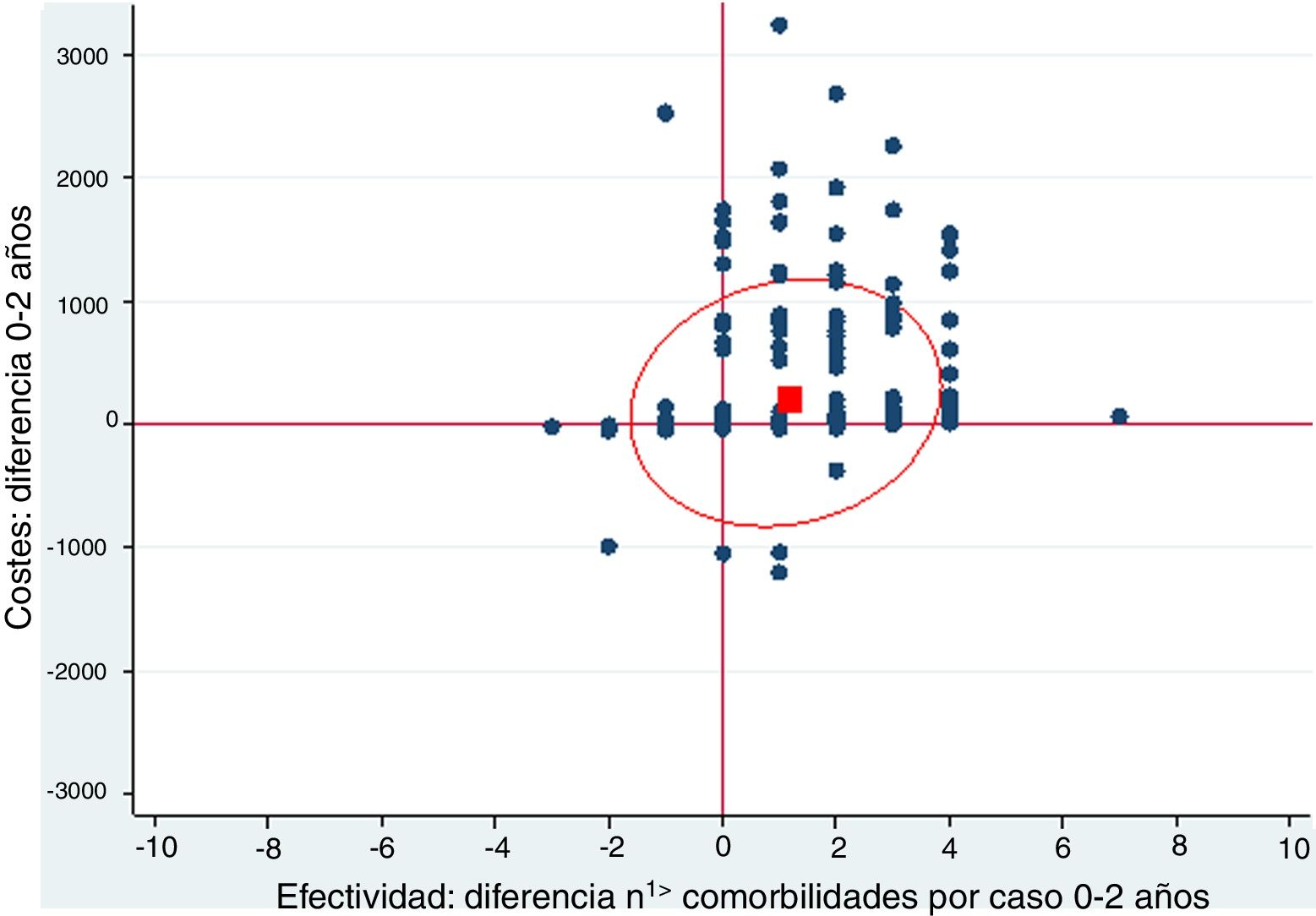

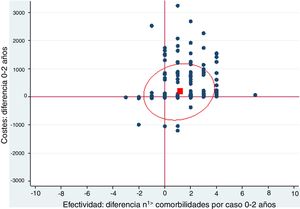

A cost-effectiveness chart was created, in which the X-axis expressed the general effectiveness of bariatric surgery as a function of the difference in the number of comorbidities, and the Y-axis represented cost, referring to the difference in expenses after surgery. Due to the great heterogeneity of drugs and prices, there was no clear proportionality between the decrease in the number of comorbidities and savings. The outcome obtained showed that the majority of points were located in the area of cost-effectiveness, indicating that the surgery was cost-effective in general (Fig. 1).

Cost-effectiveness chart.

‘Positive difference’ means ‘savings’. The fact that the values are positive is because the data are presented as differences. The effectiveness is expressed as the difference in comorbidities the month prior and 2 years after surgery; therefore, in most cases this difference is a positive value because the number of comorbidities descends. In the costs, the result is expressed as difference in costs, and in most cases this difference is positive because there is a predominance of savings.

The red box represents the mean cost-effectiveness; the ellipse represents the confidence interval of the mean. Each point can represent one or more cases.

Costs: difference 0–2 years

Effectiveness: difference n1> comorbidities per case 0–2 years

Morbid obesity is a serious health problem, but it also poses a challenge for financing the public healthcare system. Thus, medical interventions that reduce the percentage of obese people and their associated diseases will result in significant savings in healthcare costs for the population.5–7

The prospective Delphi study8 describes that, in Spain, obesity is responsible for 43% of the total cost of T2DM, 32% of arthropathies and more than 30% of heart conditions, which demonstrates both its clinical and economic relevance.

There are several studies and meta-analyses with series between 3000 and 12 000 patients that show the evolution of comorbidities after undergoing bariatric surgery.9–12 Along general lines, remission of T2DM has been demonstrated in 86.6%, improved or resolved hyperlipidemia in 70%, HTN in 61.7% and OSA in 83%. Therefore, it can be said that bariatric surgery is the best treatment for morbid obesity and its associated comorbidities.

In our study, the pathology with the best remission rate in the three surgical groups was OSA. T2DM had excellent results after metabolic bypass, which is the technique that encompasses the largest number of diabetic patients due to its indication. In SG, the resolution results were good, and in conventional bypass they were not significant due to the small number of patients presented. HTN obtained good remission in the three surgical groups. In both types of bypass, there was a significant resolution of the metabolic pathology, especially in metabolic bypass.

A more modest decrease that is not statistically significant is described in cardiovascular, osteoarticular and psychiatric pathologies. In general, these results can be justified because their relationship with obesity is not as direct as in the aforementioned pathologies and because they are established, chronic pathologies that are difficult to resolve despite weight loss. As an exception, it should be noted that there was a significant increase in osteoarticular pathology after SG surgery, but this is probably due to the fact that this surgical group included patients with the highest BMI.

In endocrine pathology, there were no changes in prevalence after surgery, suggesting that obesity is a consequence of hypothyroidism, but not the other way around. It is important to highlight the group of ‘other comorbidities’, since this was the only one that presented an increase in prevalence in the three surgical groups, mainly due to vitamin and nutritional deficiencies secondary to bariatric surgery.

Regarding the total savings in medications brought about by the post-bariatric surgery improvement in comorbidities, the data in the literature are controversial due to the variety between different studies. In the prospective study by Sampalis et al.13 the mean number of treatments per patient decreased by 66%, and the cut-off point for the cost-effectiveness ratio was 2.5 years after surgery. The study by Mäklin et al.14 concluded that the bariatric surgery option represents a saving of €16 130 per patient. In the study by Christou,15 the healthcare costs of the non-treated group far exceeded the cost of the surgical patients after the third year of follow-up.

When represented in a cost-effectiveness chart, our general data demonstrate that, as effectiveness increases through the reduction in the number of comorbidities, pharmacological expenditure is reduced, which suggests that bariatric surgery is a cost-effective technique.16–19 However, the different particularities of each surgical group must be taken into account.

In the SG group, the resolution of comorbidities is accompanied by a cost difference of €137 per month. T2DM is the pathology that represents the most important savings, not only because of its good response but also because antidiabetic drugs are the most expensive in the study. The next best result is obtained in HTN. The rest of the pathologies that are resolved after surgery also involve savings, although somewhat less striking. The increased prevalence of osteoarticular pathology that is evident after 2 years does not translate into an increase in costs, and the group of ‘other comorbidities’ is the only one that increased the costs.

In metabolic bypass, the resolution of different comorbidities implies a total difference in monthly costs of €507. This good result is justified by the association between T2DM and metabolic bypass, since its diagnosis determines the indication for the technique, and this pathology is the most cost-effective in the study. The remission of hypertension generates the next-best savings, although it is very far from T2DM. In the case of metabolic pathology, it is striking that the good resolution is not accompanied by significant savings, but the drugs in this group are very inexpensive. On the other hand, this technique has the highest percentage of patients in the ‘other comorbidities’ group 2 years after surgery, meaning a higher cost in terms of vitamin and nutritional supplements, which would translate into an increase in costs. However, the significant savings in T2DM render this slight increase in pharmacological costs insignificant.

Compared to conventional bypass, the results are very different. The costs involved are very low and may even slightly increase after surgery. The key to this poor outcome is the absence of T2DM, as only 2.8% of diabetic patients were included in this group. This reflects the first few cases collected, when the difference between the two bypass techniques was not yet so standardized in our hospital. Therefore, the savings involved are due to the resolution of hypertension and metabolic pathology, which, as already mentioned, are quite modest values. On the other hand, as it is a mixed technique, a significant increase in the group of ‘other comorbidities’ was observed 2 years after surgery because of vitamin and nutritional supplements, implying an increase in costs like in metabolic bypass. But in this case, this increase is not offset by savings, contrary to what happens in metabolic bypass.

The strengths of this study are the large number of patients, which provides greater rigor, and the numerous variables analyzed. Having collected the pharmacological expenditure in euros per month, despite having been carried out with maximum objectivity, would perhaps be a weakness because of its lower reproducibility. Another limitation would be that, after 2 years of follow-up, the group of ‘other comorbidities’ includes both comorbidities resulting from bariatric surgery as well as those related to obesity itself, so the origin of drug expenditure within this group cannot be determined.

After bariatric surgery, the results may worsen 5 years after surgery, including regained weight, re-appearance of comorbidities, and increased pharmacological costs. Thus, we should consider an analysis of these data as a future line of research.

We conclude that the decrease in pharmacological costs 2 years after bariatric surgery is demonstrated in general terms, implying that the role of this procedure is fundamental for the resolution of the comorbidities associated with morbid obesity. However, the peculiarities of each surgical technique and the comorbidities studied must be considered, as all cases do not demonstrate the same benefit.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Granel Villach L, Laguna Sastre JM, Ibáñez Belenguer JM, Beltrán Herrera HA, Queralt Martín R, Fortea Sanchis C, et al. Análisis del impacto de la cirugía bariátrica en el gasto farmacológico a medio plazo. Cir Esp. 2021;99:737–744.