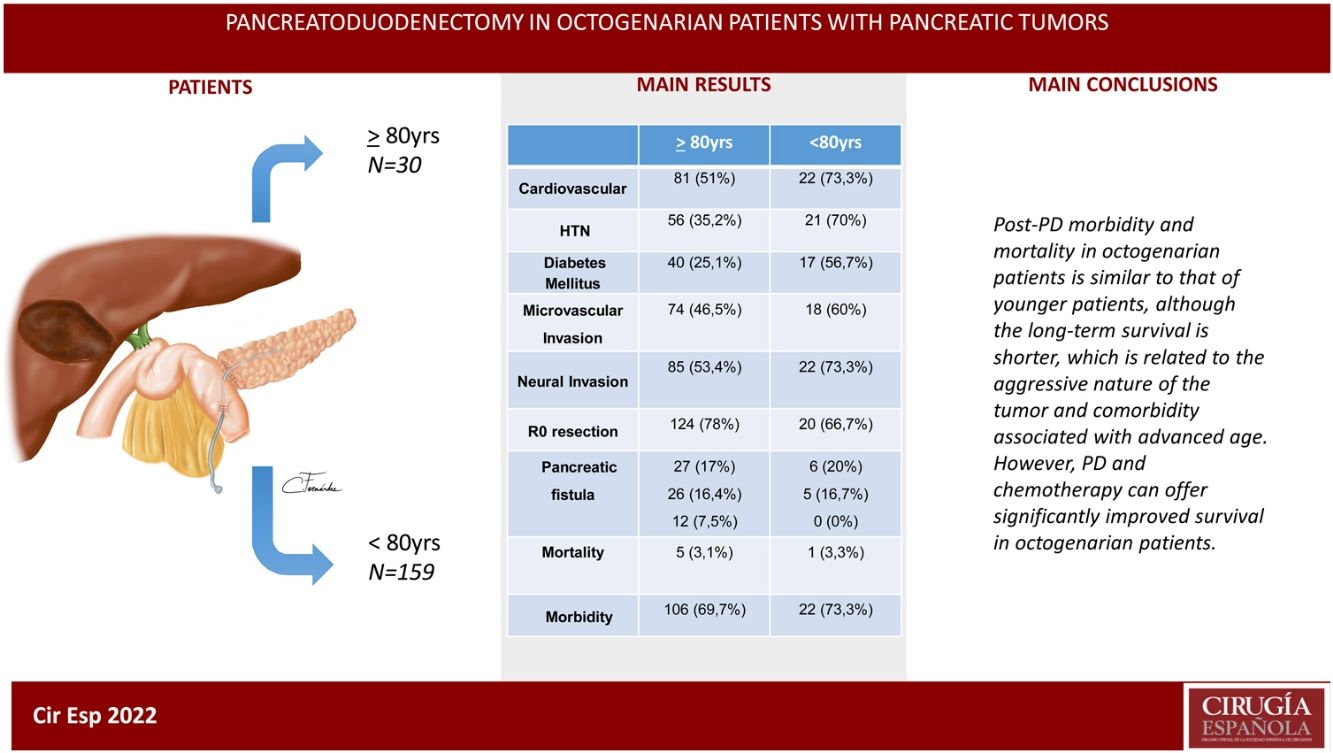

Current literature supports the claim that performing a cephalic pancreaticoduodenectomy (CPD) as treatment for pancreatic cancer (PC) is associated with an increase in median survival, both in octogenarian (≥80 years) patients as well as younger patients.

MethodsThis is a retrospective and comparative trial, comparing results for CPD performed on 30 patients ≥80 years with PC and 159 patients <80 years.

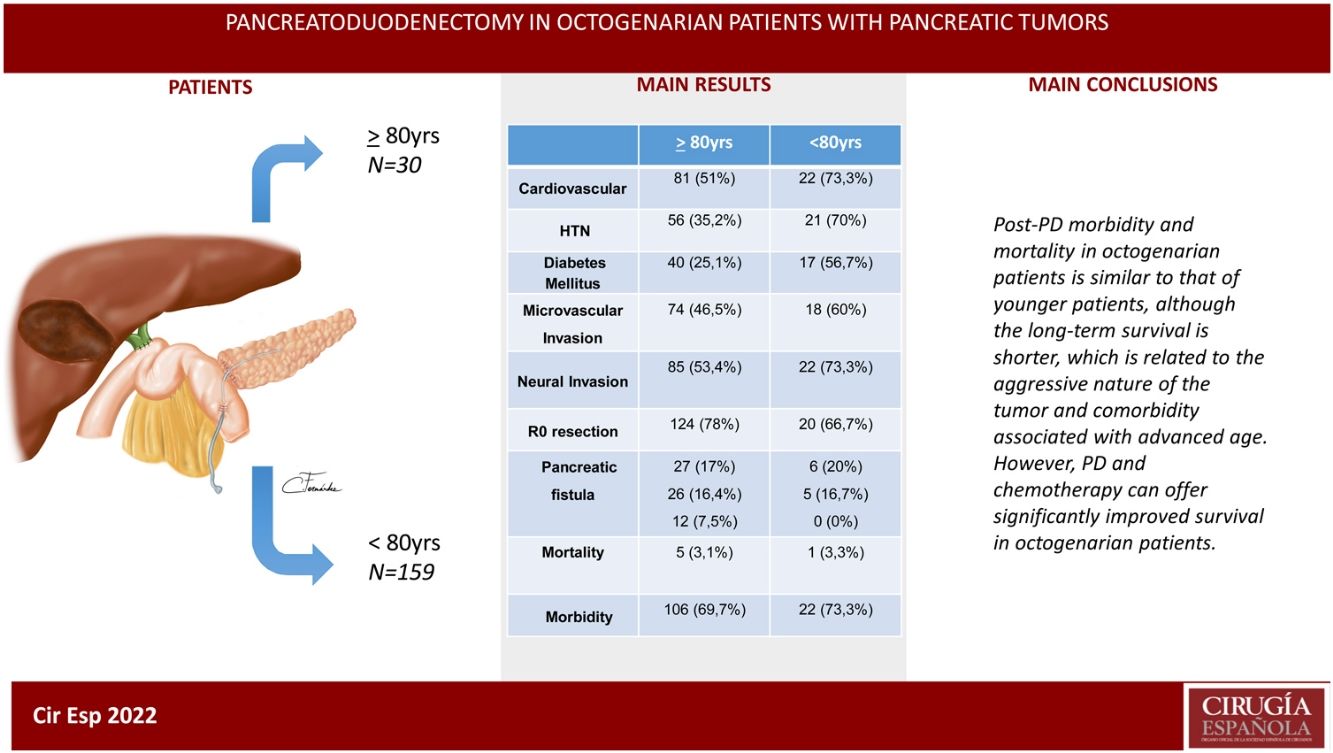

ResultsThe patients in the octogenarian group showed a significantly higher rate of preoperative cardiovascular morbidity and a more aggressive tumoral behaviour, including more significant preoperative anemia, jaundice and levels of CA 19-9, higher vascular and neural invasion, and a lower rate of R0 resection despite using the same surgical technique. There were no significant differences in terms of postoperative complications. Postoperative mortality was similar in both groups (3.3% in octogenarians vs 3.1% in patients <80 years). Mortality during follow-up was mainly due to tumour recurrence, cardiovascular complications and COVID-19 in 2 elderly patients.

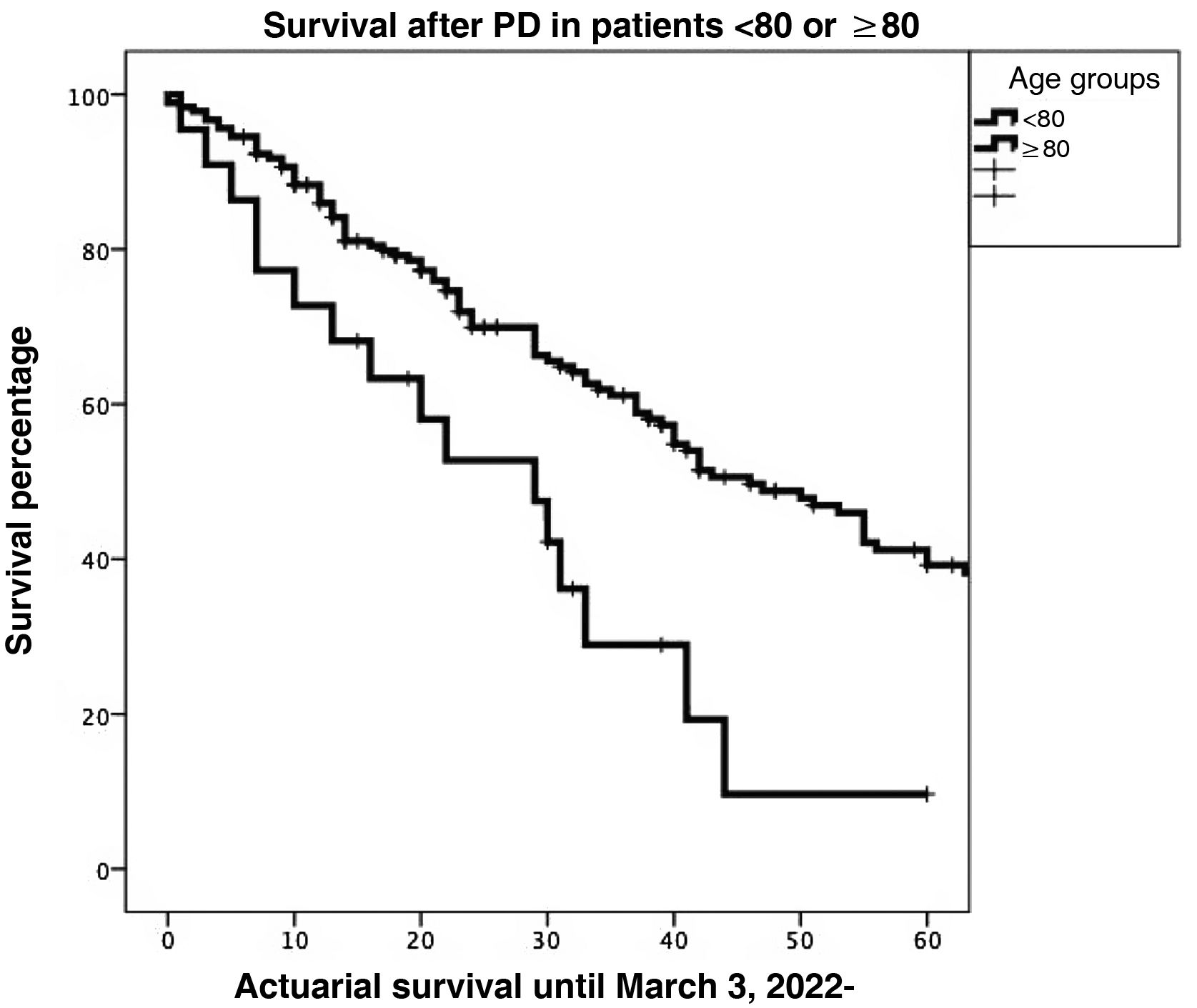

Actuarial survival at 1, 3 and 5 years was significantly larger for patients <80 years old, as compared to octogenarians (85.9%, 61.1% and 39.2% versus 72.7%, 28.9% and 9.6%, respectively; P = 0.001). The presence of a pancreatic fistula and not using external Wirsung stenting were significantly associated with 90-day postoperative mortality after a CPD.

ConclusionsMorbidity and mortality post-CPD is similar in octogenarians and patients younger than 80, although long-term survival is shorter due to more aggressive tumours and comorbidities associated with older age.

Según estudios previos, la duodenopancreatectomía cefálica (DPC) por cáncer de páncreas (CP) se asocia a un incremento de la supervivencia mediana tanto en pacientes octogenarios como en pacientes de menor edad.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo y comparativo de la DPC realizada en 30 pacientes ≥ 80 con CP y en 159 pacientes < 80 años.

ResultadosLos pacientes octogenarios presentaban una tasa significativamente mayor de morbilidad cardiovascular preoperatoria y un comportamiento tumoral más agresivo (mayor anemia, ictericia y CA 19-9 preoperatorios, invasión vascular y neural y menor frecuencia de resección R0 a pesar de utilizar la misma técnica quirúrgica). No hubo diferencias significativas en cuanto a complicaciones postoperatorias. La mortalidad postoperatoria fue similar en ambos grupos (3,3% en octogenarios versus 3,1% en < 80 años). Las causas de mortalidad durante el seguimiento fueron fundamentalmente por recidiva tumoral, complicaciones cardiovasculares y COVID-19 (2 octogenarios).

La supervivencia actuarial a 1, 3 y 5 años fue significativamente mayor en pacientes < 80 años que en octogenarios (el 85,9%, el 61,1 y el 39,2% versus el 72,7, el 28,9 y el 9,6%, respectivamente; p = 0,001). En el estudio multivariable, la presencia de una fístula pancreática y la no utilización de tutor externo del Wirsung influyeron de forma estadísticamente significativa sobre la mortalidad a 90 días post-DPC.

ConclusionesLa morbimortalidad post-DPC es similar en octogenarios y < 80 años, aunque la supervivencia a largo plazo es menor por la agresividad tumoral y comorbilidad asociada a la edad avanzada.

The incidence of pancreatic cancer (PC) has progressively increased in recent decades,1 a fact that has been attributed to obesity, diabetes, a sedentary lifestyle, and consumption of tobacco and fats.2-4 Due to the low survival rate of PC, the associated incidence and mortality present similar rates (4.8 and 4.4/100 000 people, respectively).4 In Europe, PC is currently predicted to surpass breast cancer in incidence, becoming the 3rd leading cause of cancer-related death.5 Spain has a population of 2 285 352 (4.76%) octogenarians6 with the longest life expectancy in Europe (82.3 years in 2020), which logically also involves a higher incidence of PC (8697 cases in 2021)7 due to the increase in incidence as age progresses, even in those over 85 years of age.8

Pancreatectomy associated with chemotherapy is the standard therapy for the potential cure of PC.9 However, despite the improved results with these therapies, advanced patient age continues to be a reason for exclusion from surgical treatment10 due to the perception of higher postoperative risk associated with increasing age.11 Thus, only 51% of an American series of 10 505 patients with locoregional PC with a mean age of 77.1 ± 7.1 years were managed with one of the following treatments: surgery and chemotherapy (11.1%), surgery (10.8%) or chemotherapy (29.1%).12 Recently, according to the database of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society, only 44.5% of patients >80 years of age received oncological treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy). Meanwhile, an overall benefit in survival was observed in these octogenarian patients treated, even though higher mortality was detected than in the younger patients.13

The decrease in postoperative mortality in older patients with PC is attributed to improved patient selection, the application of surgical and anesthetic techniques, and postoperative patient care.11

Since the early 1990s, in large-volume pancreatic surgery services, pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) has become a safe procedure for head of the pancreas and periampullary tumors, even in patients >80 years of age, which was confirmed by mortality rates of less than 5%.14–16 However, the decision to perform PD in patients ≥80 years of age with head of the pancreas tumor remains controversial and difficult to accept for many surgeons due to the frailty associated with advanced age, surgical trauma, the poor prognosis of the disease17–19 and the impact of age on the results of surgery.20

The objective of this retrospective study is to analyze the results obtained when performing PD for pancreatic head tumors in a group of patients ≥80 years of age compared to a control group of patients <80 years of age.

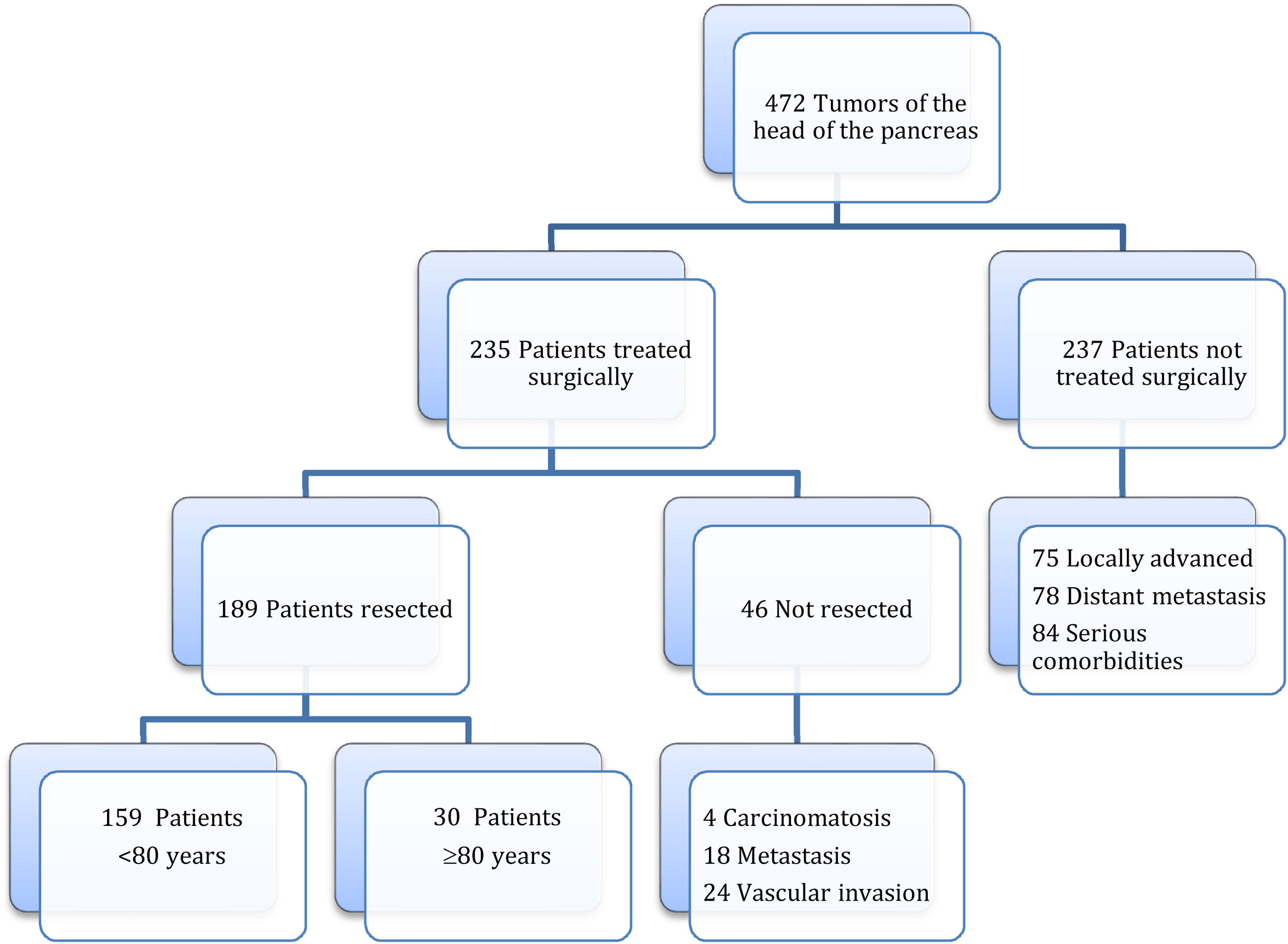

MethodsAccording to the Tumor Registry at our hospital, between January 19, 2012 and August 30, 2021, tumors of the head of the pancreas were diagnosed in 472 patients, and surgery was contraindicated in 237 patients due to locally advanced or metastatic tumors or due to severe associated comorbidity. Surgery was indicated in 235 patients, and PD was performed in 189 (40%), 30 of which were performed in octogenarian patients ≥80 years (study group) and 159 in patients <80 years (control group) (Fig. 1). The cohort study is retrospective, and both groups of patients were compared based on a minimum follow-up of 6 months.

In our study, the following variables were registered for both groups: preoperative variables (age, sex, body mass index [BMI], ASA classification, personal history, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, clinical history, laboratory, radiological and histological tests); intraoperative variables (duration of surgery, blood transfusion, surgical findings and techniques, histology and tumor invasion, R0 resection and TNM staging); patient evolution, postoperative morbidity and mortality (medical and surgical complications, reoperations, hospital stay and mortality), 90-day morbidity and mortality, ≥6-month follow-up, readmission rate, and adjuvant chemotherapy.

A tumor in the head of the pancreas was considered resectable under the following circumstances: no invasion of the portal vein or superior mesenteric vein (SMV); a clear dissection plane between the tumor and the celiac trunk, hepatic artery, and superior mesenteric artery (SMA); and no extrapancreatic tumor dissemination. In addition, the tumor was considered potentially resectable in cases of stenosis, invasion or obstruction of the portal vein or SMV, although while still allowing for resection and venous reconstruction. The same was true for cases in which the tumor was in contact with a short segment of the hepatic artery or <180º around the SMA. The presence of macroscopic extrapancreatic tumor spread contraindicated PD. Curative resection (R0) was confirmed by tumor-free resection margins on histological examination.

The PD technique has been previously described,21 and end-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy was performed in all cases in this series.

Pancreatic fistulae were classified according to the ISGPF update,22 biliary fistulae followed the criteria of Burkhart et al.,23 postoperative hemorrhage (POH)24 and delayed gastric emptying (DGE) according to ISGPS criteria,25 and surgical complications according to the Clavien classification, considering grade ≥ III serious.26 In-hospital mortality was defined as that which occurred during hospitalization.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were expressed as absolute numbers, and relative frequencies as a percentage. According to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, most quantitative variables have not presented a normal distribution, so all the quantitative variables have been expressed as median and 0 and 100 percentiles. The relationship between quantitative variables was analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Binary logistic regression was used to calculate the 90-day mortality odds ratio, while Cox regression was used to calculate factors that impact survival.

The survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier estimator, comparing the survival of the groups using the Mantel–Cox test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

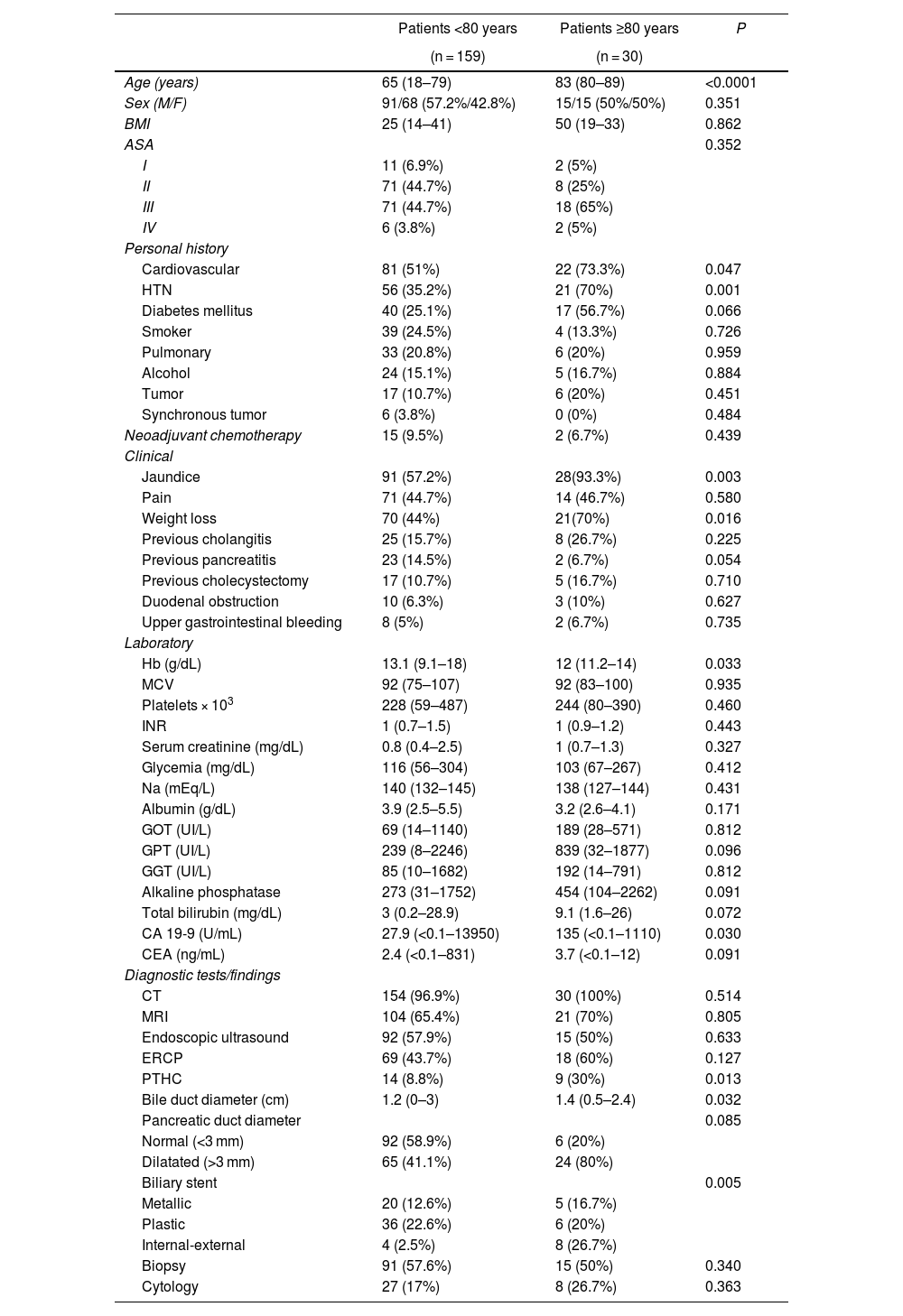

ResultsPreoperative variables. When we compared the patients in the 2 groups treated with PD, the octogenarian patients had a significantly higher rate of cardiovascular comorbidity and hypertension, and the rate of diabetes mellitus was also higher, although the difference was not statistically significant between the groups. The presence of jaundice and weight loss occurred significantly more frequently in octogenarian patients. The bile duct and pancreatic duct presented larger diameters among the octogenarian patients, although only the caliber of the bile duct was statistically significant. A preoperative biliary stent was placed more frequently in octogenarians, which was significant. Regarding the laboratory workup, hemoglobin levels were significantly lower and CA 19-9 markers significantly higher in octogenarian patients. In the comparison of the remaining preoperative variables, there were no significant differences (Table 1).

Preoperative variables of the patient groups.

| Patients <80 years | Patients ≥80 years | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 159) | (n = 30) | ||

| Age (years) | 65 (18–79) | 83 (80–89) | <0.0001 |

| Sex (M/F) | 91/68 (57.2%/42.8%) | 15/15 (50%/50%) | 0.351 |

| BMI | 25 (14–41) | 50 (19–33) | 0.862 |

| ASA | 0.352 | ||

| I | 11 (6.9%) | 2 (5%) | |

| II | 71 (44.7%) | 8 (25%) | |

| III | 71 (44.7%) | 18 (65%) | |

| IV | 6 (3.8%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Personal history | |||

| Cardiovascular | 81 (51%) | 22 (73.3%) | 0.047 |

| HTN | 56 (35.2%) | 21 (70%) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40 (25.1%) | 17 (56.7%) | 0.066 |

| Smoker | 39 (24.5%) | 4 (13.3%) | 0.726 |

| Pulmonary | 33 (20.8%) | 6 (20%) | 0.959 |

| Alcohol | 24 (15.1%) | 5 (16.7%) | 0.884 |

| Tumor | 17 (10.7%) | 6 (20%) | 0.451 |

| Synchronous tumor | 6 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.484 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 15 (9.5%) | 2 (6.7%) | 0.439 |

| Clinical | |||

| Jaundice | 91 (57.2%) | 28(93.3%) | 0.003 |

| Pain | 71 (44.7%) | 14 (46.7%) | 0.580 |

| Weight loss | 70 (44%) | 21(70%) | 0.016 |

| Previous cholangitis | 25 (15.7%) | 8 (26.7%) | 0.225 |

| Previous pancreatitis | 23 (14.5%) | 2 (6.7%) | 0.054 |

| Previous cholecystectomy | 17 (10.7%) | 5 (16.7%) | 0.710 |

| Duodenal obstruction | 10 (6.3%) | 3 (10%) | 0.627 |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 8 (5%) | 2 (6.7%) | 0.735 |

| Laboratory | |||

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.1 (9.1–18) | 12 (11.2–14) | 0.033 |

| MCV | 92 (75–107) | 92 (83–100) | 0.935 |

| Platelets × 103 | 228 (59–487) | 244 (80–390) | 0.460 |

| INR | 1 (0.7–1.5) | 1 (0.9–1.2) | 0.443 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.4–2.5) | 1 (0.7–1.3) | 0.327 |

| Glycemia (mg/dL) | 116 (56–304) | 103 (67–267) | 0.412 |

| Na (mEq/L) | 140 (132–145) | 138 (127–144) | 0.431 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 (2.5–5.5) | 3.2 (2.6–4.1) | 0.171 |

| GOT (UI/L) | 69 (14–1140) | 189 (28–571) | 0.812 |

| GPT (UI/L) | 239 (8–2246) | 839 (32–1877) | 0.096 |

| GGT (UI/L) | 85 (10–1682) | 192 (14–791) | 0.812 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 273 (31–1752) | 454 (104–2262) | 0.091 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3 (0.2–28.9) | 9.1 (1.6–26) | 0.072 |

| CA 19-9 (U/mL) | 27.9 (<0.1–13950) | 135 (<0.1–1110) | 0.030 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 2.4 (<0.1–831) | 3.7 (<0.1–12) | 0.091 |

| Diagnostic tests/findings | |||

| CT | 154 (96.9%) | 30 (100%) | 0.514 |

| MRI | 104 (65.4%) | 21 (70%) | 0.805 |

| Endoscopic ultrasound | 92 (57.9%) | 15 (50%) | 0.633 |

| ERCP | 69 (43.7%) | 18 (60%) | 0.127 |

| PTHC | 14 (8.8%) | 9 (30%) | 0.013 |

| Bile duct diameter (cm) | 1.2 (0–3) | 1.4 (0.5–2.4) | 0.032 |

| Pancreatic duct diameter | 0.085 | ||

| Normal (<3 mm) | 92 (58.9%) | 6 (20%) | |

| Dilatated (>3 mm) | 65 (41.1%) | 24 (80%) | |

| Biliary stent | 0.005 | ||

| Metallic | 20 (12.6%) | 5 (16.7%) | |

| Plastic | 36 (22.6%) | 6 (20%) | |

| Internal-external | 4 (2.5%) | 8 (26.7%) | |

| Biopsy | 91 (57.6%) | 15 (50%) | 0.340 |

| Cytology | 27 (17%) | 8 (26.7%) | 0.363 |

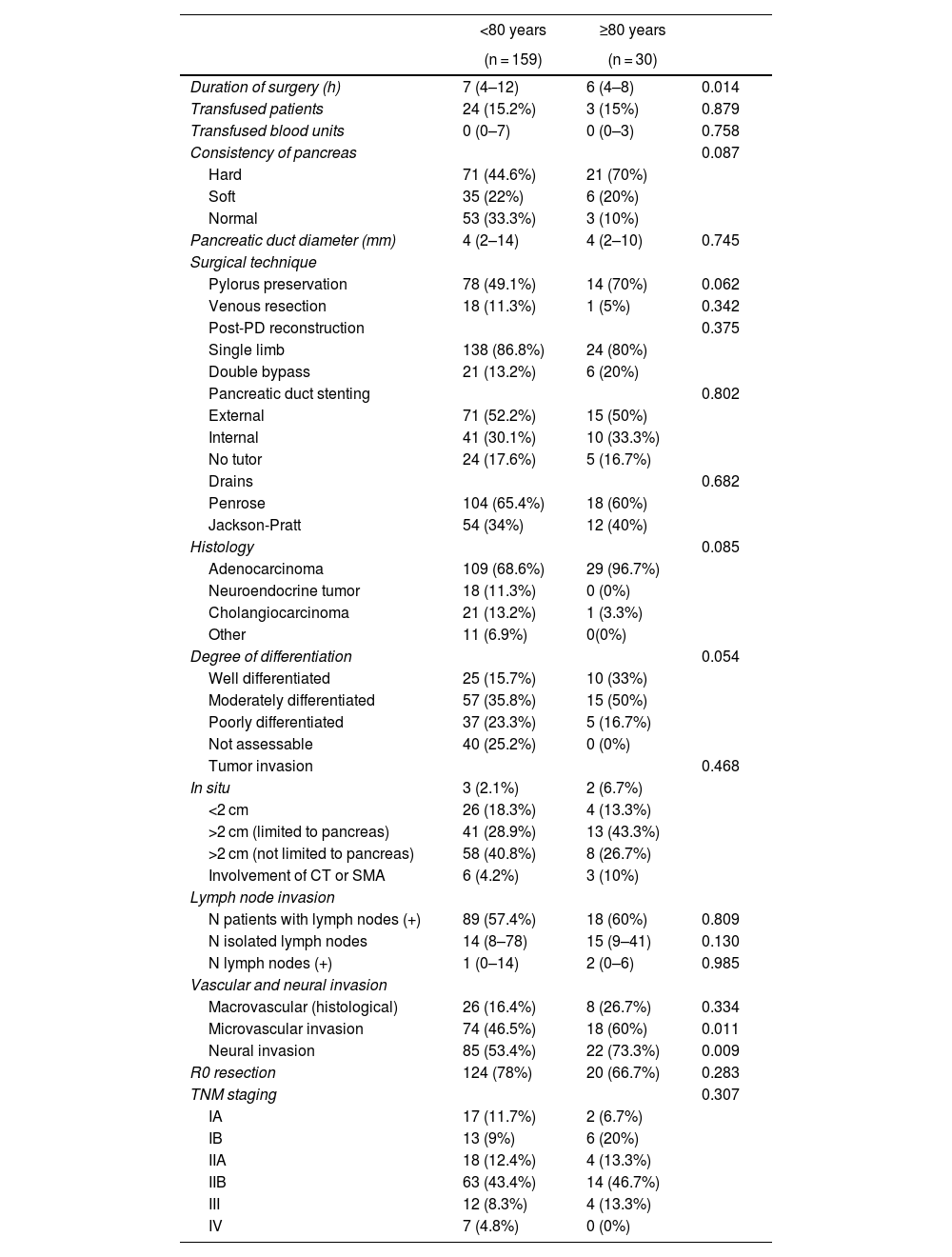

Intraoperative and histological variables. The duration of PD surgery was significantly longer in patients <80 years (P = 0.014), while microvascular (P = 0.011) and neural (P = 0.009) invasion were significantly more frequent among octogenarian patients. No significant differences were observed when we compared the remaining variables between the groups (Table 2).

Intraoperative and histological variables.

| <80 years | ≥80 years | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 159) | (n = 30) | ||

| Duration of surgery (h) | 7 (4–12) | 6 (4–8) | 0.014 |

| Transfused patients | 24 (15.2%) | 3 (15%) | 0.879 |

| Transfused blood units | 0 (0–7) | 0 (0–3) | 0.758 |

| Consistency of pancreas | 0.087 | ||

| Hard | 71 (44.6%) | 21 (70%) | |

| Soft | 35 (22%) | 6 (20%) | |

| Normal | 53 (33.3%) | 3 (10%) | |

| Pancreatic duct diameter (mm) | 4 (2–14) | 4 (2–10) | 0.745 |

| Surgical technique | |||

| Pylorus preservation | 78 (49.1%) | 14 (70%) | 0.062 |

| Venous resection | 18 (11.3%) | 1 (5%) | 0.342 |

| Post-PD reconstruction | 0.375 | ||

| Single limb | 138 (86.8%) | 24 (80%) | |

| Double bypass | 21 (13.2%) | 6 (20%) | |

| Pancreatic duct stenting | 0.802 | ||

| External | 71 (52.2%) | 15 (50%) | |

| Internal | 41 (30.1%) | 10 (33.3%) | |

| No tutor | 24 (17.6%) | 5 (16.7%) | |

| Drains | 0.682 | ||

| Penrose | 104 (65.4%) | 18 (60%) | |

| Jackson-Pratt | 54 (34%) | 12 (40%) | |

| Histology | 0.085 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 109 (68.6%) | 29 (96.7%) | |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 18 (11.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 21 (13.2%) | 1 (3.3%) | |

| Other | 11 (6.9%) | 0(0%) | |

| Degree of differentiation | 0.054 | ||

| Well differentiated | 25 (15.7%) | 10 (33%) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 57 (35.8%) | 15 (50%) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 37 (23.3%) | 5 (16.7%) | |

| Not assessable | 40 (25.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Tumor invasion | 0.468 | ||

| In situ | 3 (2.1%) | 2 (6.7%) | |

| <2 cm | 26 (18.3%) | 4 (13.3%) | |

| >2 cm (limited to pancreas) | 41 (28.9%) | 13 (43.3%) | |

| >2 cm (not limited to pancreas) | 58 (40.8%) | 8 (26.7%) | |

| Involvement of CT or SMA | 6 (4.2%) | 3 (10%) | |

| Lymph node invasion | |||

| N patients with lymph nodes (+) | 89 (57.4%) | 18 (60%) | 0.809 |

| N isolated lymph nodes | 14 (8–78) | 15 (9–41) | 0.130 |

| N lymph nodes (+) | 1 (0–14) | 2 (0–6) | 0.985 |

| Vascular and neural invasion | |||

| Macrovascular (histological) | 26 (16.4%) | 8 (26.7%) | 0.334 |

| Microvascular invasion | 74 (46.5%) | 18 (60%) | 0.011 |

| Neural invasion | 85 (53.4%) | 22 (73.3%) | 0.009 |

| R0 resection | 124 (78%) | 20 (66.7%) | 0.283 |

| TNM staging | 0.307 | ||

| IA | 17 (11.7%) | 2 (6.7%) | |

| IB | 13 (9%) | 6 (20%) | |

| IIA | 18 (12.4%) | 4 (13.3%) | |

| IIB | 63 (43.4%) | 14 (46.7%) | |

| III | 12 (8.3%) | 4 (13.3%) | |

| IV | 7 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

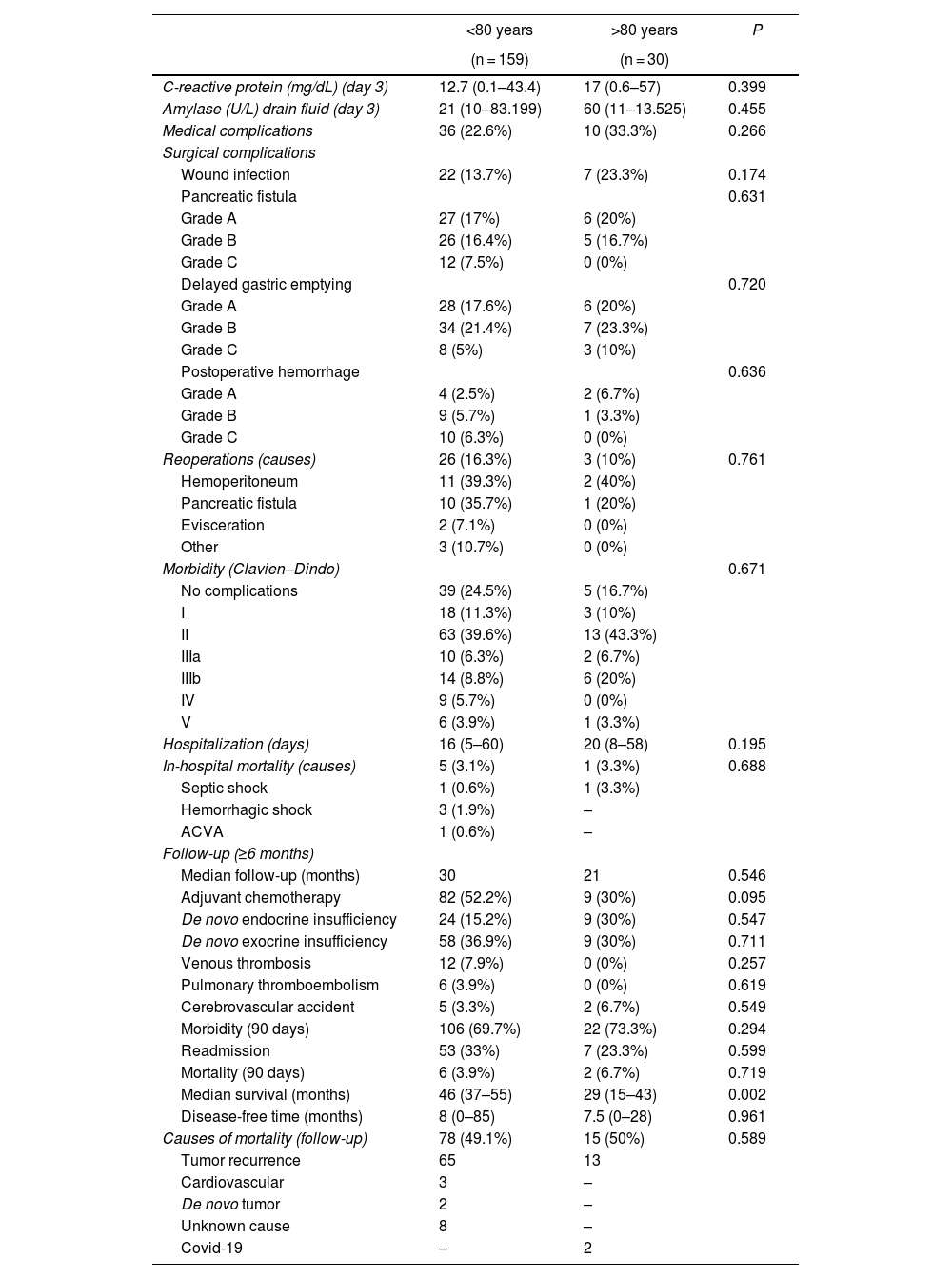

Evolution, postoperative morbidity/mortality and follow-up. For these variables, no statistically significant differences were detected in the comparison of the variables between the groups. Hospital stay was longer in octogenarian patients (median 20 vs 16 days in <80 years; P = 0.195). In-hospital mortality was similar in both groups (3.1% in <80 years vs 3.3% in octogenarians; P = 0.195).

Adjuvant chemotherapy was used more frequently in patients <80 years of age than in octogenarians, although the difference was not significant (52.2% vs 30%; P = 0.095). The incidence of post-PD diabetes was higher in octogenarians than in patients <80 years, although the difference was not significant (30% vs 15.2%; P = 0.547), while exocrine insufficiency was similar in both groups. Morbidity within 90 days of surgery was similar in both groups (69.7% in <80 years and 73.3% in octogenarians), as was the readmission rate (33.3% in <80 years and 23.3% in octogenarians; P = 0.599). Mortality was higher in octogenarians than in patients <80 years, but the difference was not significant (6.7% vs 3.9%; P = 0.719). The median survival of octogenarian patients was 29 months compared to 46 months the <80 group (P = 0.002). Mortality during follow-up was similar in both groups (49.1% in <80 and 50% in octogenarians; P = 0.589), mainly due to tumor recurrence, and Covid-19 in 2 octogenarian patients (Table 3).

Postoperative evolution, morbidity and mortality.

| <80 years | >80 years | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 159) | (n = 30) | ||

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) (day 3) | 12.7 (0.1–43.4) | 17 (0.6–57) | 0.399 |

| Amylase (U/L) drain fluid (day 3) | 21 (10–83.199) | 60 (11–13.525) | 0.455 |

| Medical complications | 36 (22.6%) | 10 (33.3%) | 0.266 |

| Surgical complications | |||

| Wound infection | 22 (13.7%) | 7 (23.3%) | 0.174 |

| Pancreatic fistula | 0.631 | ||

| Grade A | 27 (17%) | 6 (20%) | |

| Grade B | 26 (16.4%) | 5 (16.7%) | |

| Grade C | 12 (7.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 0.720 | ||

| Grade A | 28 (17.6%) | 6 (20%) | |

| Grade B | 34 (21.4%) | 7 (23.3%) | |

| Grade C | 8 (5%) | 3 (10%) | |

| Postoperative hemorrhage | 0.636 | ||

| Grade A | 4 (2.5%) | 2 (6.7%) | |

| Grade B | 9 (5.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | |

| Grade C | 10 (6.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Reoperations (causes) | 26 (16.3%) | 3 (10%) | 0.761 |

| Hemoperitoneum | 11 (39.3%) | 2 (40%) | |

| Pancreatic fistula | 10 (35.7%) | 1 (20%) | |

| Evisceration | 2 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 3 (10.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Morbidity (Clavien–Dindo) | 0.671 | ||

| No complications | 39 (24.5%) | 5 (16.7%) | |

| I | 18 (11.3%) | 3 (10%) | |

| II | 63 (39.6%) | 13 (43.3%) | |

| IIIa | 10 (6.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | |

| IIIb | 14 (8.8%) | 6 (20%) | |

| IV | 9 (5.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| V | 6 (3.9%) | 1 (3.3%) | |

| Hospitalization (days) | 16 (5–60) | 20 (8–58) | 0.195 |

| In-hospital mortality (causes) | 5 (3.1%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0.688 |

| Septic shock | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (3.3%) | |

| Hemorrhagic shock | 3 (1.9%) | – | |

| ACVA | 1 (0.6%) | – | |

| Follow-up (≥6 months) | |||

| Median follow-up (months) | 30 | 21 | 0.546 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 82 (52.2%) | 9 (30%) | 0.095 |

| De novo endocrine insufficiency | 24 (15.2%) | 9 (30%) | 0.547 |

| De novo exocrine insufficiency | 58 (36.9%) | 9 (30%) | 0.711 |

| Venous thrombosis | 12 (7.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0.257 |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 6 (3.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0.619 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 5 (3.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 0.549 |

| Morbidity (90 days) | 106 (69.7%) | 22 (73.3%) | 0.294 |

| Readmission | 53 (33%) | 7 (23.3%) | 0.599 |

| Mortality (90 days) | 6 (3.9%) | 2 (6.7%) | 0.719 |

| Median survival (months) | 46 (37–55) | 29 (15–43) | 0.002 |

| Disease-free time (months) | 8 (0–85) | 7.5 (0–28) | 0.961 |

| Causes of mortality (follow-up) | 78 (49.1%) | 15 (50%) | 0.589 |

| Tumor recurrence | 65 | 13 | |

| Cardiovascular | 3 | – | |

| De novo tumor | 2 | – | |

| Unknown cause | 8 | – | |

| Covid-19 | – | 2 | |

Survival. One-, 3- and 5-year actuarial survival rates were significantly higher in patients <80 years of age than in octogenarians (85.9%, 61.1%, and 39.2% vs 72.7%, 28.9%, and 9.6%, respectively; P = 0.001) (Fig. 2).

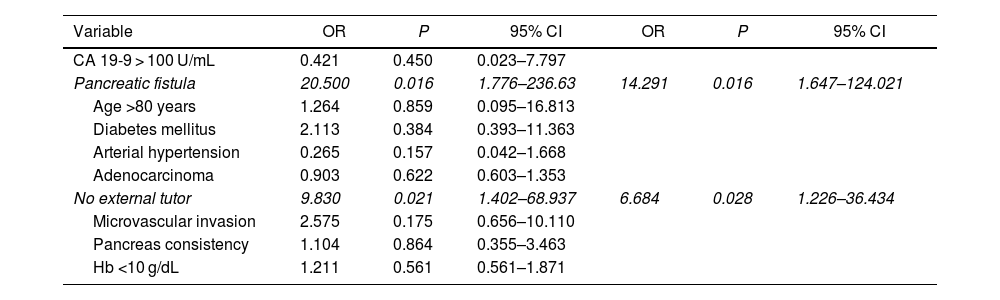

Multivariate study. The presence of a pancreatic fistula and the non-use of external stenting of the pancreatic duct had a statistically significant influence on 90-day post-PD mortality (Table 4).

Multivariate analysis for 90-day mortality.

| Variable | OR | P | 95% CI | OR | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA 19-9 > 100 U/mL | 0.421 | 0.450 | 0.023–7.797 | |||

| Pancreatic fistula | 20.500 | 0.016 | 1.776–236.63 | 14.291 | 0.016 | 1.647–124.021 |

| Age >80 years | 1.264 | 0.859 | 0.095–16.813 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.113 | 0.384 | 0.393–11.363 | |||

| Arterial hypertension | 0.265 | 0.157 | 0.042–1.668 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 0.903 | 0.622 | 0.603–1.353 | |||

| No external tutor | 9.830 | 0.021 | 1.402–68.937 | 6.684 | 0.028 | 1.226–36.434 |

| Microvascular invasion | 2.575 | 0.175 | 0.656–10.110 | |||

| Pancreas consistency | 1.104 | 0.864 | 0.355–3.463 | |||

| Hb <10 g/dL | 1.211 | 0.561 | 0.561–1.871 |

Elderly patients undergoing surgical procedures are at high risk of postoperative complications, long hospital stays, and high mortality.27,28 Although pancreatectomy can be performed safely in octogenarians, the indication for surgery or chemotherapy must be carefully discussed in a multidisciplinary session, and information should also be provided to the patient/family about the potential benefit of such therapies, possible complications, functional recovery and quality of life.19,29,30 Likewise, PD in older patients should be performed in high-volume hospitals to minimize the risk of postoperative complications.31 Logically, octogenarian patients present more preoperative comorbidity, which is reflected by a higher frequency of grades III and IV of the ASA classification,32–34 although there was no significant difference found in our study. Some authors contraindicate PC resection in ASA IV patients ≥80 years of age, especially with cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidities,33 while others are reluctant to treat these patients surgically based on the short expected survival associated with age and surgery.35 As in previous studies,20,36 we have observed significantly higher cardiovascular comorbidity and hypertension in octogenarian patients, with a trend towards statistical significance in the incidence of diabetes mellitus. The presence of jaundice and weight loss were also significantly more frequent in octogenarians. Among the laboratory data, the significantly lower hemoglobin level and the significantly higher CA 19-9 value among octogenarian patients were also findings that reflect a worse clinical situation in this older age group. No differences were found in the frequency of diagnostic tests performed in either group, except for a significantly higher frequency of percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTHC) and placement of biliary stents or drains in octogenarians due to a higher incidence of jaundice and bile duct dilation. Other authors also report a greater tendency towards preoperative biliary drainage in patients >70 years based on the impact of sustained jaundice on nutrition and renal function.37

As previously published,38 the diameter of the Wirsung duct was larger (>3 mm in 80% of patients) and the consistency of the pancreas was harder (70%) in the octogenarian patients of our series. These factors tend to favor the performance of pancreaticojejunal anastomosis and a lower incidence of grades B + C pancreatic fistulae (23.9% in <80 years vs 16.7% in ≥80). The surgical technique (vascular resection, post-PD reconstruction and pancreatic duct stenting) has been similar in both age groups, except for the higher frequency of pyloric preservation and significantly shorter duration of surgery in octogenarians. Adenocarcinoma was more common among octogenarian patients, and only microvascular and neural invasion were significantly more frequent in this age group. The degree of tumor differentiation, pancreatic and lymph node invasion, and TNM staging were similar in both groups. The number of isolated lymph nodes in our series was also similar in the 2 age groups, unlike another series where a greater number of isolated nodes was reported in the lymphadenectomies of patients >70 years of age.37 The behavior of PC is usually more aggressive in older patients,39 which seems to be confirmed in our study by the greater preoperative anemia, jaundice and CA 19-9, reported vascular and neural invasion, and the lower frequency of R0 resection among octogenarians. Our rate of portomesenteric resection was similar between the groups, and it has been previously published that patients >70 years of age treated with PD and portomesenteric resection presented a higher, although not significant, rate of postoperative complications than younger patients.39

In recent experiences with more than 50 cases of PD in patients >80 years of age, postoperative mortality ranged from 1.9% to 6.2% and morbidity from 45.2% to 52.7%.19,20,27,29,32,37,40,41 Our in-hospital mortality (3.1% in <80 years vs 3.3% in octogenarians) is similar to previous publications, while the hospital stay was longer among octogenarians, logically due to their higher morbidity and poorer health status.20,37 Regarding the medical and surgical complications of the present study, no statistically significant differences were found between the groups. However, morbidity and mortality are very discordant between different series and meta-analyses comparing octogenarian patients with younger ones. A recent meta-analysis has shown an overall increase in complications in octogenarian patients that specifically resulted in a higher incidence of delayed gastric emptying in octogenarians. However, the rates of biliary or pancreatic fistulae or postoperative hemorrhage in octogenarian and younger patients remained similar, while the mortality rate of octogenarian patients was double the rate among the younger patients.34 A previous meta-analysis of 9 PD series found only 2 series where morbidity and postoperative hospital stay were significantly higher in octogenarians than in younger patients. The study concluded that octogenarian patients present significantly higher morbidity and mortality, cardiac complications and longer hospital stay than younger patients.18 Furthermore, other studies show no statistically significant differences in terms of postoperative mortality in people over and under 80 years of age.8,11,19,29,36,37 The most frequent causes of mortality are usually related to underlying comorbidity or non-specific surgical complications, acute myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, percutaneous coronary artery stent placement, use of corticosteroids, and ascites.18,20,34,36,42

Patients >70 years of age with PC benefit more from surgery than from palliative treatments and, as in our experience, the most frequent cause of mortality is tumor recurrence and not advanced patientage.37 Circumstantially, due to the pandemic, 2 octogenarian is patient age in our series died of Covid-19 with no signs of tumor recurrence. One article argues that PD may be beneficial for octogenarian patients, since their average life expectancy is estimated to be 9.1 years.8 According to a recent meta-analysis, median post-PD survival ranges from 10 to 33 months in octogenarians versus 12–40 months in patients <80 years,34 while our median was 29 months in octogenarians versus 46 in patients <80 years.

Actuarial survival outcomes one, 3, and 5 years after surgery for octogenarian patients was significantly lower than for patients aged <80 years. Other authors have reported similar survival rates in patients over and under 80.33,36 Likewise, in the multivariate analysis of our series on 90-day mortality, the non-use of external pancreatic stenting and pancreatic fistula were shown to be risk factors for 90-day mortality, but age ≥80 years was not. In another multivariate analysis of a multicenter series, 3 risk factors for survival were identified (venous, arterial, and lymph node tumor invasion), while chemotherapy treatment was shown to be a protective factor.36

Our readmission rate was somewhat lower in octogenarian patients (23.3%) than in younger patients (33.3%), although this difference was not significant. However, a recent series has reported a 90-day postoperative readmission rate that was significantly higher in octogenarian patients compared to younger patients (42.9% vs 22.3%).28

Until now, adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been used less frequently in octogenarian patients,37,43 and its use has recently increased because it contributes to a decrease in mortality and an increase in resectability and survival.10,12,16,19,43–45 Failure to complete adjuvant chemotherapy in octogenarians (usually due to postoperative complications) has correlated with shorter post-PD survival.19,37 Among other factors, the poorer survival among our group of octogenarian patients may be partly related to the significantly higher degree of microvascular and neural invasion, and the lower frequency (although not statistically significant) of R0 resection and chemotherapy treatment in octogenarians. As we have also shown in our multivariate analysis, advanced chronological age (≥80) per se should not be a reason to contraindicate PD; it is more important to assess the biological age, which correlates better with the results.27,28,33,45 As future strategies to improve the results of PD for pancreatic tumors in octogenarian patients, patients who can withstand pancreatectomy should be carefully selected, taking into account the resectability of the tumor, evaluation of preoperative fragility, comorbidities, experience of the surgeon, nutritional support, multimodal rehabilitation and adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy treatment.10,12,29,33,34,45–47

The limitations of this study are due to its retrospective nature and the small sample of only 30 octogenarian patients.

In conclusion, post-PD morbidity and mortality results in octogenarian patients are similar to those of younger patients, although long-term survival is shorter, which is related to tumor aggressiveness and comorbidity associated with advanced age. However, PD should not be contraindicated in octogenarian patients based solely on age but should instead be accepted after a complete multidisciplinary evaluation. Chemotherapy associated with surgery can offer significantly improved survival.

Contribution of the authors- -

Iago Justo Alonso: composition of the article, critical review and approval of the final version; study design.

- -

Laura Alonso Murillo: data collection; analysis and interpretation of the results.

- -

Alberto Marcacuzco Quinto: study design and data collection.

- -

Oscar Caso Maestro: data collection; analysis and interpretation of the results.

- -

Paula Rioja Conde: data collection.

- -

Clara Fernández: data collection.

- -

Carlos Jiménez-Romero: study design; composition of the article; critical review and approval of the final version.

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.