Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) is a set of symptoms (sensation of fullness, epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting) that appears in the absence of mechanical obstruction1–5 and can occur after surgeries in the supramesocolic region6. It is usually resolved with prokinetics and aspiration, although it may occasionally require surgical or interventional treatment, which prolongs hospital stay and increases healthcare costs5,6.

In pancreatic surgery, DGE after pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) has been widely studied, observing high percentages (11%–60%)1–3,6 and a general association with postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF)1,3,6. In 2007, the International Study Group for Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) published a classification for DGE after pancreatic surgery, divided into 3 categories according to severity, which was quickly accepted internationally.

However, few studies have been published about the incidence of DGE after distal pancreatectomy (DP), which ranges from 5%–24%5,6. The predisposing factors are also not clearly defined. This paper analyzes the incidence of DGE in a multicenter DP series and identifies the associated factors.

This is a retrospective observational study of DP conducted by 8 medium-high volume hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery units (mean volume 10–40 pancreatectomies/year, high volume >40 pancreatectomies/year)7 between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2018. The study included all DP performed for any diagnosis, except for patients who underwent urgent surgery, DP associated with resection of the celiac trunk, and minor patients under the age of 18. DGE was defined according to the ISGPS1 classification. We studied epidemiological, clinical, serum, diagnostic, surgical, histological variables and postoperative complications. Quantitative data were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR) and qualitative data as frequencies or percentages. In the case of quantitative variables, differences between groups were analyzed using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test and the Pearson chi-square test was applied for differences between percentages.

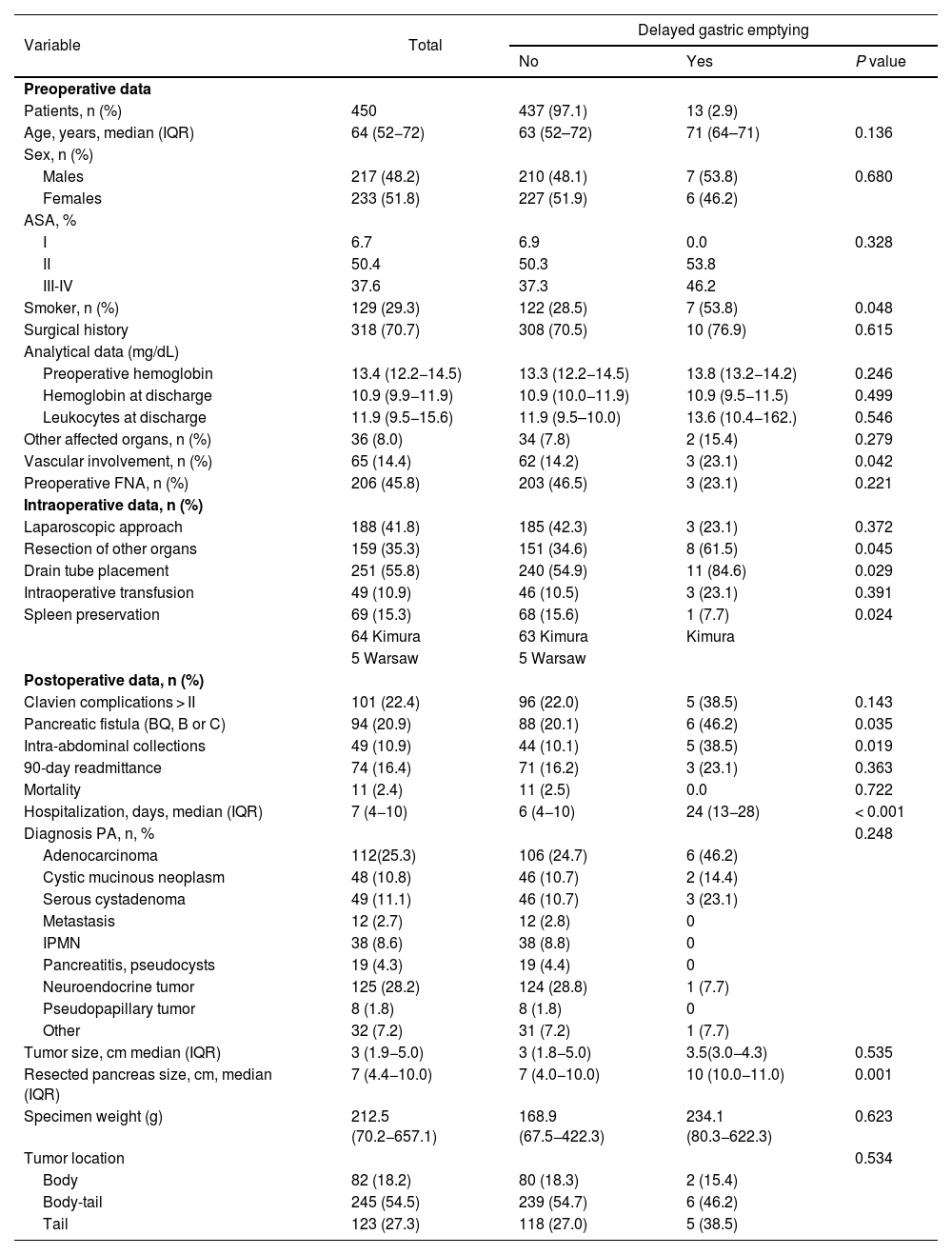

We have reviewed 450 DP. In 41.8% of cases, the approach was laparoscopic, mostly for neuroendocrine tumors and pancreatic cystic tumors. This percentage was 24.2% from 2008 to 2013, which increased to 63.3% from 2013 to 2018. The conversion rate was 8.5%. ERAS protocols existed in 3 of the 8 hospitals at the beginning of the study period, and these were gradually implemented in the remaining study centers. Drain tubes were systematically placed in 7 of the 8 hospitals, with early removal (<72 h) if amylase levels were less than 3 times the reference serum amylase levels at each medical center. Table 1 reports the pre-, intra-, and post-operative data. Thirteen patients presented DGE (2.9%): 7 (53.8%) grade A, 5 (38.5%) grade B, and 1 (7.7%) grade C. The median age was 71 years, and 53.8% were men. These patients had a longer hospital stay (6 vs 24 days). Likewise, they presented statistically significant differences for: smoking habit, splenic vascular involvement, resection of adjacent organs, drain tube placement, presence of POPF, intra-abdominal collections, and larger size of the resected pancreas (Table 1). In these patients, there was a lower percentage of laparoscopic approach and a higher rate of transfusion and major complications (Clavien-Dindo >II). Five patients presented intra-abdominal collections. One patient was treated with percutaneous drainage, 2 with transgastric drainage, and 2 with antibiotic therapy. One patient required surgery for gastric perforation. All cases were treated with prokinetics, nasogastric tube (median 12 days [6–22]), and parenteral nutrition. In one case, gastrojejunostomy was performed to resolve the DGE.

Comparison between patients with/without delayed gastric emptying.

| Variable | Total | Delayed gastric emptying | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | P value | ||

| Preoperative data | ||||

| Patients, n (%) | 450 | 437 (97.1) | 13 (2.9) | |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 64 (52−72) | 63 (52–72) | 71 (64–71) | 0.136 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Males | 217 (48.2) | 210 (48.1) | 7 (53.8) | 0.680 |

| Females | 233 (51.8) | 227 (51.9) | 6 (46.2) | |

| ASA, % | ||||

| I | 6.7 | 6.9 | 0.0 | 0.328 |

| II | 50.4 | 50.3 | 53.8 | |

| III-IV | 37.6 | 37.3 | 46.2 | |

| Smoker, n (%) | 129 (29.3) | 122 (28.5) | 7 (53.8) | 0.048 |

| Surgical history | 318 (70.7) | 308 (70.5) | 10 (76.9) | 0.615 |

| Analytical data (mg/dL) | ||||

| Preoperative hemoglobin | 13.4 (12.2−14.5) | 13.3 (12.2−14.5) | 13.8 (13.2−14.2) | 0.246 |

| Hemoglobin at discharge | 10.9 (9.9−11.9) | 10.9 (10.0−11.9) | 10.9 (9.5−11.5) | 0.499 |

| Leukocytes at discharge | 11.9 (9.5−15.6) | 11.9 (9.5–10.0) | 13.6 (10.4−162.) | 0.546 |

| Other affected organs, n (%) | 36 (8.0) | 34 (7.8) | 2 (15.4) | 0.279 |

| Vascular involvement, n (%) | 65 (14.4) | 62 (14.2) | 3 (23.1) | 0.042 |

| Preoperative FNA, n (%) | 206 (45.8) | 203 (46.5) | 3 (23.1) | 0.221 |

| Intraoperative data, n (%) | ||||

| Laparoscopic approach | 188 (41.8) | 185 (42.3) | 3 (23.1) | 0.372 |

| Resection of other organs | 159 (35.3) | 151 (34.6) | 8 (61.5) | 0.045 |

| Drain tube placement | 251 (55.8) | 240 (54.9) | 11 (84.6) | 0.029 |

| Intraoperative transfusion | 49 (10.9) | 46 (10.5) | 3 (23.1) | 0.391 |

| Spleen preservation | 69 (15.3) | 68 (15.6) | 1 (7.7) | 0.024 |

| 64 Kimura | 63 Kimura | Kimura | ||

| 5 Warsaw | 5 Warsaw | |||

| Postoperative data, n (%) | ||||

| Clavien complications > II | 101 (22.4) | 96 (22.0) | 5 (38.5) | 0.143 |

| Pancreatic fistula (BQ, B or C) | 94 (20.9) | 88 (20.1) | 6 (46.2) | 0.035 |

| Intra-abdominal collections | 49 (10.9) | 44 (10.1) | 5 (38.5) | 0.019 |

| 90-day readmittance | 74 (16.4) | 71 (16.2) | 3 (23.1) | 0.363 |

| Mortality | 11 (2.4) | 11 (2.5) | 0.0 | 0.722 |

| Hospitalization, days, median (IQR) | 7 (4−10) | 6 (4−10) | 24 (13−28) | < 0.001 |

| Diagnosis PA, n, % | 0.248 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 112(25.3) | 106 (24.7) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Cystic mucinous neoplasm | 48 (10.8) | 46 (10.7) | 2 (14.4) | |

| Serous cystadenoma | 49 (11.1) | 46 (10.7) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Metastasis | 12 (2.7) | 12 (2.8) | 0 | |

| IPMN | 38 (8.6) | 38 (8.8) | 0 | |

| Pancreatitis, pseudocysts | 19 (4.3) | 19 (4.4) | 0 | |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 125 (28.2) | 124 (28.8) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Pseudopapillary tumor | 8 (1.8) | 8 (1.8) | 0 | |

| Other | 32 (7.2) | 31 (7.2) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Tumor size, cm median (IQR) | 3 (1.9−5.0) | 3 (1.8−5.0) | 3.5(3.0−4.3) | 0.535 |

| Resected pancreas size, cm, median (IQR) | 7 (4.4−10.0) | 7 (4.0−10.0) | 10 (10.0−11.0) | 0.001 |

| Specimen weight (g) | 212.5 (70.2−657.1) | 168.9 (67.5−422.3) | 234.1 (80.3−622.3) | 0.623 |

| Tumor location | 0.534 | |||

| Body | 82 (18.2) | 80 (18.3) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Body-tail | 245 (54.5) | 239 (54.7) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Tail | 123 (27.3) | 118 (27.0) | 5 (38.5) | |

IQR: interquartile range; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists classification; AP: anatomic pathology; FNA: Fine needle aspiration; BQ: biochemical fistula; PA: pathological anatomy; IPMN: intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm.

DGE-DP occurred in 2.9% of the patients in the series, a rate that is lower than previously published series5–10. In all published DGE-DP studies, increased hospital stay is observed5–8, as is the case of this study.

The etiological factors of DGE after PD have been studied extensively. The following have been suggested: hormonal alterations after duodenal resection, gastric ischemia and denervation, POPF, and mechanical alterations6. Of these, only ischemic gastropathy when there is gastric ischemia in DP associated with celiac trunk resection6,8,9 and POPF are applicable to DP.

The etiological factors of DGE-DP have not been determined, although it has been related to: age >75 years6,9, diagnosis of malignancy7, laparotomic approach5,7, clinically relevant POPF5,6 (B/C), resection of the celiac trunk8,10, and major complications (Clavien-Dindo >II), highlighting the presence of intra-abdominal collections6,9. There are no evident etiopathogenic mechanisms except for POPF, post-resection ischemic gastropathy of the celiac trunk and abdominal collections, which explains why the mentioned factors increase DGE. In this paper, only POPF and intra-abdominal collections were also confirmed as factors associated with DGE, while the other parameters were not. However, we have also observed other factors that have not been previously studied, such as splenic vascular involvement or the length of the resected pancreas.

The limitations of this study are its retrospective nature and, as it is multicenter, the lack of common protocols for intraoperative use and subsequent removal of the nasogastric tube and initiation of oral tolerance. In the same way, the small number of cases with DGE prevents having sufficient statistical power to be able to affirm which factors influence the appearance of DGE. The strength of the study is that it is a series that includes a large number of patients. In conclusion, DGE can occur after DP, and we must keep this in mind when a patient who has undergone DP presents symptoms compatible with DGE.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.