Delayed gastric emptying is one of the most frequent complications after pancreatoduodenectomy.

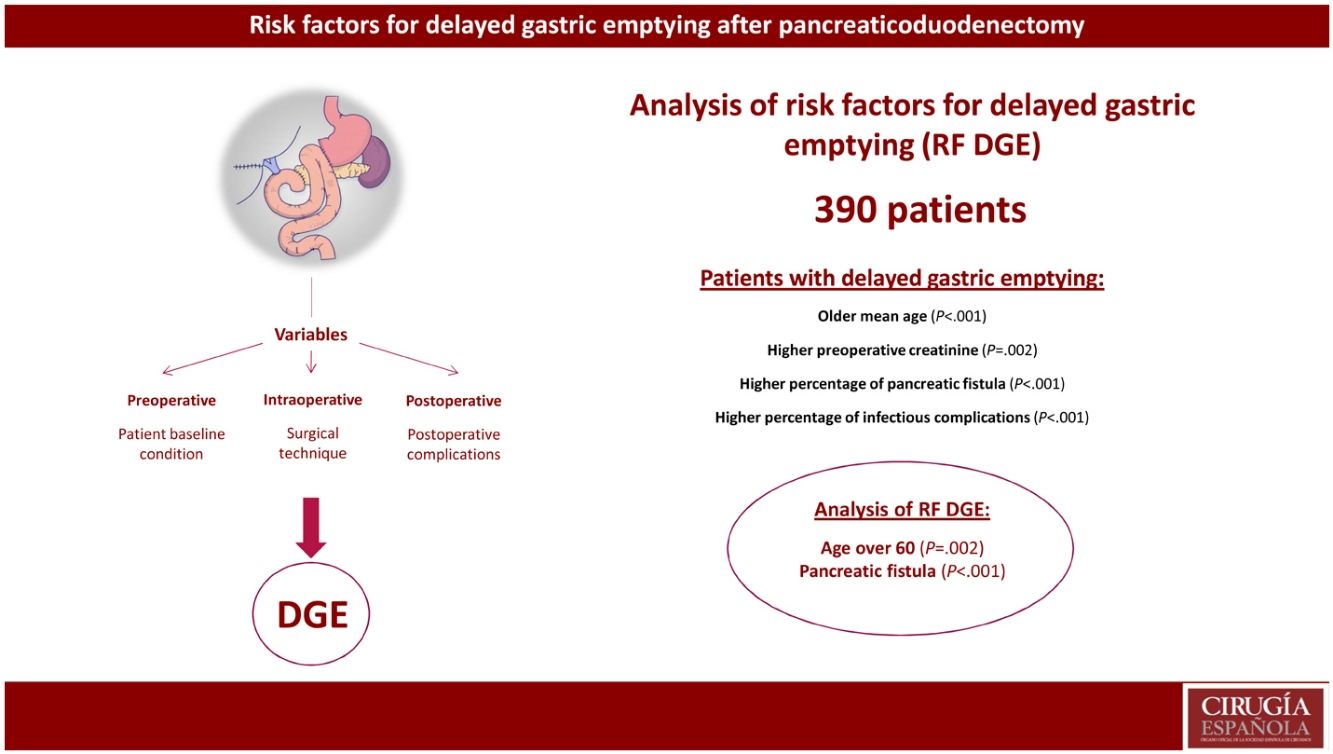

MethodsWe performed an analysis of risk factors for delayed gastric emptying on a prospective database of 390 patients operated on between 2013 and 2021. A comparative retrospective study was carried out between patients with and without delayed gastric emptying and subsequently a study of risk factors for delayed gastric emptying using univariate and multivariate logistic regression models.

ResultsThe incidence of delayed gastric emptying in the overall series was 28%. The morbidity of the group was 63%, and postoperative mortality was 3.1%. Focusing on delayed gastric emptying, the median age (73 years vs 68 years, P < 0.001) and preoperative creatinine (75 vs 65.5, P < 0.001) were higher in the group with this complication. The study of risk factors showed that age over 60 years (P = 0.002) and pancreatic fistula (P < 0.001) were risk factors for delayed gastric emptying.

ConclusionThe presence of pancreatic fistula is confirmed as a risk factor for slow gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy. In addition, age over 60 years is shown to be a risk factor for slow gastric emptying.

El vaciamiento gástrico lento (VGL) es una de las complicaciones más frecuentes tras la duodenopancreatectomía cefá lica. El objetivo del actual estudio es analizar los factores de riesgo de su aparición.

MétodosAnálisis de factores de riesgo de VGL sobre una base de datos prospectiva de 390 pacientes intervenidos entre 2013 y 2021. Se realizó un estudio retrospectivo comparativo entre pacientes con y sin VGL y posteriormente un estudio de factores de riesgo de VGL mediante modelos de regresión logística univariante y multivariante.

ResultadosLa incidencia de VGL en el global de la serie fue del 28%. Un 63% de los pacientes presentaron alguna complicación y la mortalidad postoperatoria fue del 3,1%. Se evidenció que la edad mediana (73 años vs. 68 años, p < 0,001) y la creatinina preoperatorias (75 vs. 68.5, p < 0,001) eran superiores en el grupo VGL. El estudio de factores de riesgo evidenció que la edad superior a 60 años (p = 0,002) y la fístula pancreática (p < 0,001) eran factores de riesgo de VGL.

ConclusionesLa presencia de fístula pancreática se confirma como factores de riesgo de VGL tras la duodenopancreatectomía. Además, se demuestra que la edad superior a 60 años es un factor de riesgo de VGL.

Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) continues to be one of the most frequent complications after pancreatoduodenectomy (PD), with an incidence between 13.5% and more than 40%.1–4

Various technical details in the resection phase of pancreatoduodenectomy, such as performing a Whipple-type PD versus pylorus-preserving PD,5,6 the extension of the lymph node dissection7 or division of the left gastric vein,8 have been studied as risk factors for DGE. Likewise, several modifications in the surgical technique in the reconstruction phase have been proposed to reduce DGE after PD. These include performing an antecolic gastroenteric anastomosis,9 Billroth I reconstruction for gastroenteric anastomosis,10 or Braun enteroenterostomy.11

Certain patient characteristics have been proposed as factors associated with DGE. However, there is little scientific evidence about the analysis of risk factors for this complication.1,3,4,12 Two recently published studies of more than 10 000 patients have shown that advanced age could be a risk factor for DGE, although this fact has yet to be confirmed.12,13

Given the concern in the international literature in this regard, our group has studied this postoperative problem for years.5,14 As a result, we have standardized our surgical technique with antrectomy and antecolic gastroenteroanastomosis. However, despite the efforts of pancreatic surgeons, DGE continues to be a relevant problem, while its etiology is not fully understood on certain occasions.

Our intention is to analyze the causes of DGE after PD in detail, and then be able to propose a solution, if there is one. Our hypothesis is that, as is known, the presence of a pancreatic fistula may be related to DGE. However, we do not know which preoperative variables are relevant or how nutritional status can transcend the appearance of said complication. Thus, the objective of this study is to analyze in depth the risk factors for DGE after PD.

MethodsBetween 2013 and 2021, we prospectively recorded patients who underwent PD at our hospital. All surgeries were performed by a team experienced in pancreatic surgery. All patients who had been treated surgically were included in the study, regardless of the indication; cases of pancreatic cancer that required widening of the margin during surgery were also included. Data were recorded in a prospective database, including preoperative clinical, laboratory, intraoperative, pathological, and postoperative morbidity data.

Registered postoperative complications were defined according to SGPS criteria and definitions.15 DGE and DGE severity grades were defined according to ISGPS criteria.16

A narrow pancreatic duct was defined as a duct with a diameter less than or equal to 3 mm. Pancreatic fistula was defined by the discharge of amylase-rich drainage fluid after the third postoperative day and classified according to the International Pancreatic Fistula Study Group.15 Type B and C pancreatic fistulae have been grouped in our study as clinically relevant pancreatic fistulae. Postoperative morbidity included the appearance of any complication during the hospital stay. In the postoperative period and during hospitalization, complications were defined according to the Clavien-Dindo classification.17 Perioperative mortality was defined as death during hospitalization or within 90 days of surgery if the patient had been discharged earlier. Readmissions were recorded within 90 days after surgery.

In accordance with the protocol of our hospital, preoperative patient assessment was carried out by the digestive surgery team. The preoperative lab work-up included blood bilirubin, albumin, etc. Preoperative biliary drainage was not performed systematically but was instead indicated only in patients whose final management was uncertain or who had an expected delay in surgery of more than 2 weeks.

PD was performed following the previously described technique.18,19 The surgical procedure began with exploratory laparoscopy, converting to laparotomy in the absence of distant disease. A right subcostal laparotomy was performed, with thorough and systematic exploration of the abdominal cavity. If signs of extension of the disease were observed, a preoperative biopsy was taken; if positive, resection was contraindicated and biliodigestive bypass was performed. All patients underwent resection with curative intent. The technique performed was PD, with lymphadenectomy that included the peri-pancreatic and peri-duodenal lymphatic tissue. Surgery was begun with cholecystectomy, lymphadenectomy of the hepatic hilum, and division of the bile duct, then continuing with the mobilization of the duodenum and right colon. After division of the stomach and proximal jejunum and uncrossing the intestine, the uncinate pancreas was dissected until completing the lymph node dissection of the right portion of the superior mesenteric artery and completing the PD. The resection specimen was sent for frozen section analysis of the margin of the neck of the pancreas. In the case of distal cholangiocarcinoma, a section of the margin of the proximal hepatic duct was submitted for fresh tissue study. Margin involvement made it necessary to extend the resection of the bile duct, with another tissue analysis and resection of the hepatic duct up to the bifurcation of the bile duct. The pathology study was performed by the same pathologist in all cases. The inclusion of the piece followed a resection margin protocol with analysis of the retroperitoneal margin, neck of the pancreas margin, and the analysis of the lymph node territories. In our experience, we found no differences between pyloric preservation and antrectomy in terms of DGE5; therefore, starting in 2011, all patients underwent PD with antrectomy. Reconstruction was performed with a single intestinal loop, to which the pancreas, bile duct, and duodenum were consecutively anastomosed. The first-choice pancreatojejunal anastomosis was end-to-side duct-to-mucosa or inserted end-to-end anastomosis if the duct was narrow. Lastly, two suction drains were placed close to the pancreatojejunal and biliodigestive anastomoses.

Likewise, we included patients who were part of the randomized PAUDA trial,14 both the study group (Roux-en-Y reconstruction) and the control group (Billroth II reconstruction). In the aforementioned study, which included 80 patients, it was ruled out that performing a Roux-en-Y gastroenteroanastomosis would decrease the incidence of delayed gastric emptying, and when we conducted a study of risk factors for this complication, hyperbilirubinemia and hypoalbuminemia were associated with a higher incidence. This present study includes an analysis of DGE risk factors in a larger group of patients, without taking into account the type of intestinal reconstruction performed, since it had been evaluated in a previous randomized clinical trial.

During the postoperative period, the patients were managed in the Postoperative Resuscitation Unit without nasogastric tubes. A liquid diet was initiated 12 h after the procedure.14 An antiemetic drug (ondansetron 4 mg/8 h) was prescribed systematically, adding metoclopramide (10 mg/8 h) in case of nausea. Analgesia during the first 48 h was based on metamizole (2 g/8 h) and paracetamol (1 g/8 h). Amylase was analyzed systematically in the fluid discharged from the surgical drains between the 3rd and 4th postoperative days. Rescue analgesia was based on intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) at a dose of 0.5 mg morphine per bolus, with a maximum of 24 mg/4 h. After the first 48 h, PCA was withdrawn including intravenous metamizole (2 g/8 h) and paracetamol (1 g/8 h).

If there were no notable incidents in the postoperative period, the patient was transferred to the hospital ward, where oral intake progressed following the ERAS protocol of our medical center. In the case of DGE, management was based on nil per os, placement of a nasogastric tube, and administration of antiemetics. No diagnostic test was routinely performed, but an endoscopic and radiological study was performed in patients with grade B or C DGE. Associated complications were also treated, if there were any.

Statistical studyWe conducted a retrospective study based on prospective data collection. For each variable, we carried out an initial descriptive study with measures of association according to the appearance of DGE: for categorical variables, we used absolute numbers and percentages as well as the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test; for quantitative variables, we calculated medians and interquartile ranges, as well as the Student’s t or Mann–Whitney U test For the analysis of DGE risk factors, a multivariate logistic regression model was designed, taking variables with P-value <.2 in the univariate model, as well as those considered clinically relevant. The statistical analysis was performed with Stata 13.0 (StataCorp, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, Texas 77845 USA).

Lastly, we created a risk factor analysis for delayed gastric emptying using univariate logistic regression models. For the multivariate analysis, significant variables from the univariate study were selected, as well as demographic variables (age and sex) and pre-/postoperative variables that were clinically considered related to DGE. P < 0.050 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® version 18 software (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

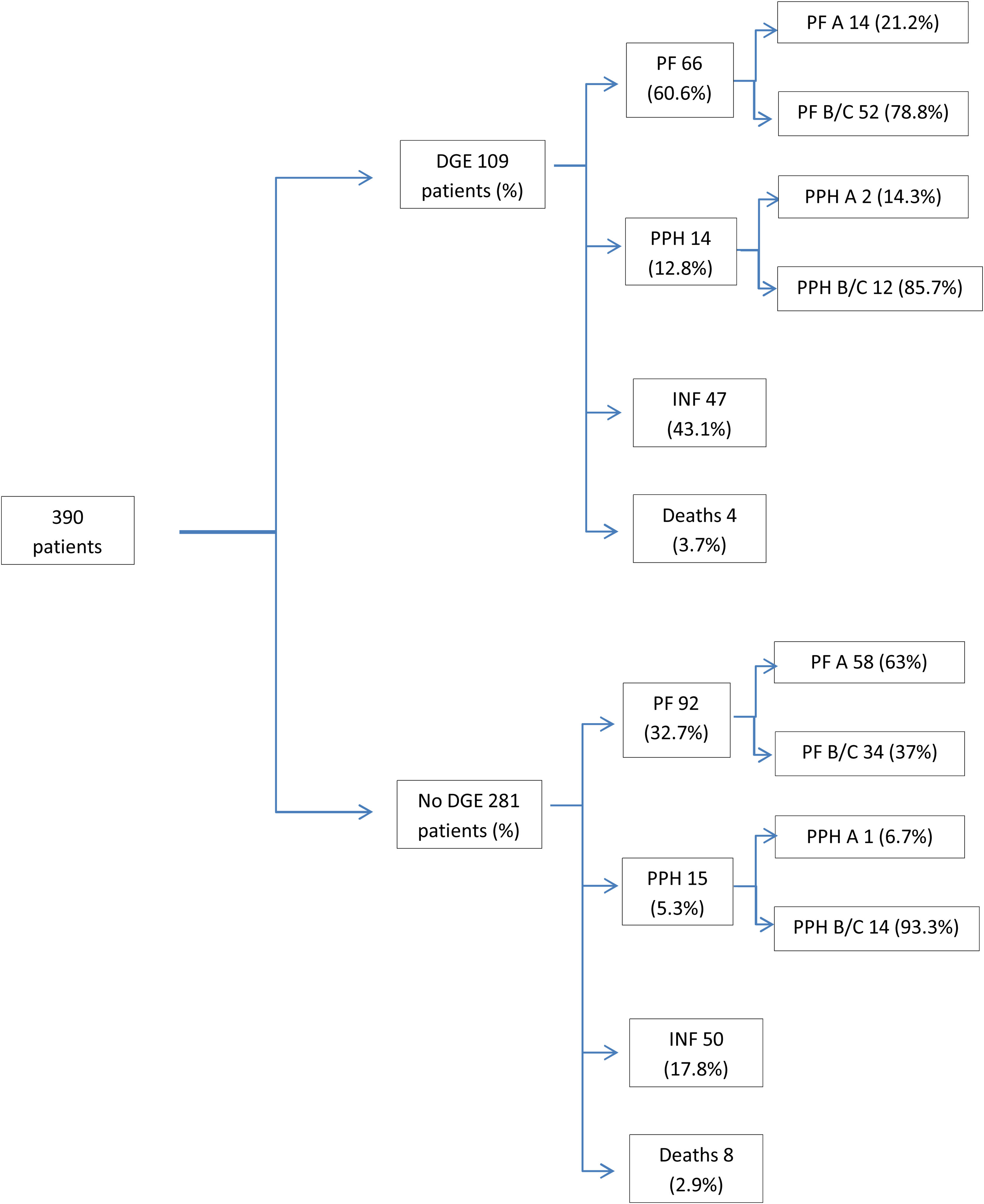

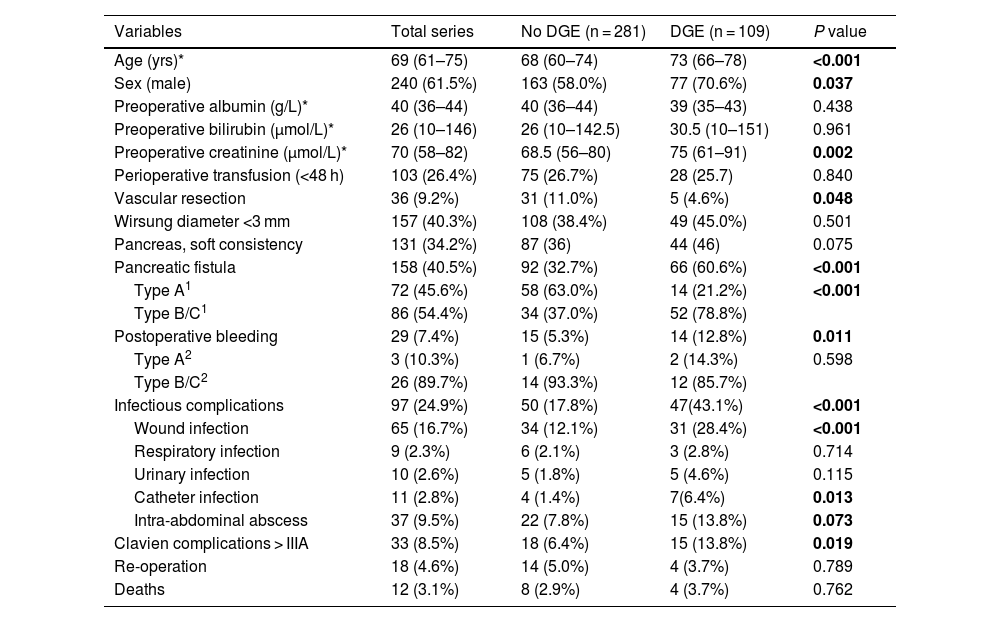

ResultsDuring the study period, 390 patients were operated on, with a mean age of 72 years (±10.9), and 62% were men. Regarding the postoperative evolution, 245 patients (63%) presented some type of complication, and in the overall group a postoperative mortality rate of 3.1% was observed (Table 1, Fig. 1). The causes of death were: respiratory failure in 4 patients, association of pancreatic fistula and hemorrhage in 4 more patients, and vein graft thrombosis in one patient with consequent intestinal ischemia that required right hemicolectomy. The 3 remaining patients were deaths due to spinal aplasia of unknown origin in one case, arterial ischemia of the lower extremity and hemorrhagic cerebrovascular accident in another patient, and finally acute myocardial infarction in the third.

Demographic data and preoperative/postoperative variables.

| Variables | Total series | No DGE (n = 281) | DGE (n = 109) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs)* | 69 (61–75) | 68 (60–74) | 73 (66–78) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 240 (61.5%) | 163 (58.0%) | 77 (70.6%) | 0.037 |

| Preoperative albumin (g/L)* | 40 (36–44) | 40 (36–44) | 39 (35–43) | 0.438 |

| Preoperative bilirubin (μmol/L)* | 26 (10–146) | 26 (10–142.5) | 30.5 (10–151) | 0.961 |

| Preoperative creatinine (μmol/L)* | 70 (58–82) | 68.5 (56–80) | 75 (61–91) | 0.002 |

| Perioperative transfusion (<48 h) | 103 (26.4%) | 75 (26.7%) | 28 (25.7) | 0.840 |

| Vascular resection | 36 (9.2%) | 31 (11.0%) | 5 (4.6%) | 0.048 |

| Wirsung diameter <3 mm | 157 (40.3%) | 108 (38.4%) | 49 (45.0%) | 0.501 |

| Pancreas, soft consistency | 131 (34.2%) | 87 (36) | 44 (46) | 0.075 |

| Pancreatic fistula | 158 (40.5%) | 92 (32.7%) | 66 (60.6%) | <0.001 |

| Type A1 | 72 (45.6%) | 58 (63.0%) | 14 (21.2%) | <0.001 |

| Type B/C1 | 86 (54.4%) | 34 (37.0%) | 52 (78.8%) | |

| Postoperative bleeding | 29 (7.4%) | 15 (5.3%) | 14 (12.8%) | 0.011 |

| Type A2 | 3 (10.3%) | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0.598 |

| Type B/C2 | 26 (89.7%) | 14 (93.3%) | 12 (85.7%) | |

| Infectious complications | 97 (24.9%) | 50 (17.8%) | 47(43.1%) | <0.001 |

| Wound infection | 65 (16.7%) | 34 (12.1%) | 31 (28.4%) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory infection | 9 (2.3%) | 6 (2.1%) | 3 (2.8%) | 0.714 |

| Urinary infection | 10 (2.6%) | 5 (1.8%) | 5 (4.6%) | 0.115 |

| Catheter infection | 11 (2.8%) | 4 (1.4%) | 7(6.4%) | 0.013 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 37 (9.5%) | 22 (7.8%) | 15 (13.8%) | 0.073 |

| Clavien complications > IIIA | 33 (8.5%) | 18 (6.4%) | 15 (13.8%) | 0.019 |

| Re-operation | 18 (4.6%) | 14 (5.0%) | 4 (3.7%) | 0.789 |

| Deaths | 12 (3.1%) | 8 (2.9%) | 4 (3.7%) | 0.762 |

Bold values: statistically significant.

1&2: ISGPS criteria.

Clinical evolution of patients with and without DGE (associated complications are not exclusive; patients can present more than one complication).

DGE: delayed gastric emptying; PF: pancreatic fistula; PF A: pancreatic fistula, type A; PF B/C: pancreatic fistula type B/C; PPH: post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage; PPH A: post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage, type A; PPH B/C: post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage, type B/C; INF: infectious complications.

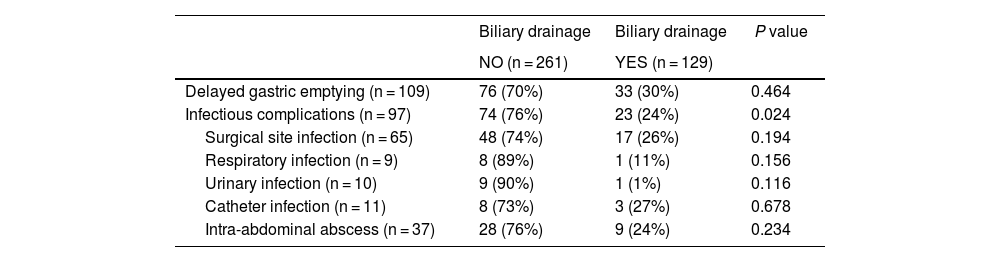

Pancreatic fistula was found in 40.5%, and bleeding complications were observed in 7.4%. Infectious complications were identified in 97 patients (25%), the most relevant being surgical site infection, which appeared in 17% of the patients. Catheter infection occurred in 2.8% of patients and intra-abdominal abscess in 9.5% of patients. The study was completed by performing a bivariate analysis to correlate infectious complications in patients with or without preoperative biliary drainage. A greater tendency towards infectious complications in general was observed as well as for each type in patients without drain tubes (Table 2).

Infectious complications, delayed gastric emptying and biliary drainage.

| Biliary drainage | Biliary drainage | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NO (n = 261) | YES (n = 129) | ||

| Delayed gastric emptying (n = 109) | 76 (70%) | 33 (30%) | 0.464 |

| Infectious complications (n = 97) | 74 (76%) | 23 (24%) | 0.024 |

| Surgical site infection (n = 65) | 48 (74%) | 17 (26%) | 0.194 |

| Respiratory infection (n = 9) | 8 (89%) | 1 (11%) | 0.156 |

| Urinary infection (n = 10) | 9 (90%) | 1 (1%) | 0.116 |

| Catheter infection (n = 11) | 8 (73%) | 3 (27%) | 0.678 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess (n = 37) | 28 (76%) | 9 (24%) | 0.234 |

We registered 28% DGE and observed that the mean age and preoperative creatinine were higher in the group with DGE compared to the rest. Regarding postoperative complications, in the DGE group there was a higher percentage of pancreatic fistula, infectious complications in general, and wound infection. In the group of patients who presented DGE as a complication, the number of patients with biliary drainage was lower than the patients without it (Table 2).

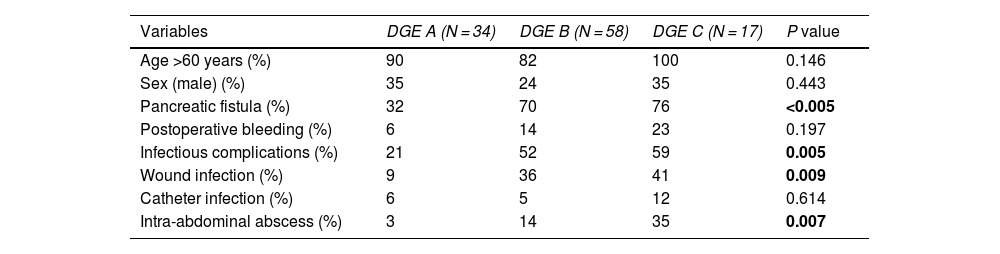

When we analyzed the severity grade of DGE, 31% were type A, 53% type B, and 16% type C. We found that patients with grade C DGE were associated with other severe complications, such as pancreatic fistula, or infectious complications, wound infection and intra-abdominal abscess (Table 3).

Baseline characteristics and degrees of DGE.

| Variables | DGE A (N = 34) | DGE B (N = 58) | DGE C (N = 17) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age >60 years (%) | 90 | 82 | 100 | 0.146 |

| Sex (male) (%) | 35 | 24 | 35 | 0.443 |

| Pancreatic fistula (%) | 32 | 70 | 76 | <0.005 |

| Postoperative bleeding (%) | 6 | 14 | 23 | 0.197 |

| Infectious complications (%) | 21 | 52 | 59 | 0.005 |

| Wound infection (%) | 9 | 36 | 41 | 0.009 |

| Catheter infection (%) | 6 | 5 | 12 | 0.614 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess (%) | 3 | 14 | 35 | 0.007 |

Bold values: statistically significant.

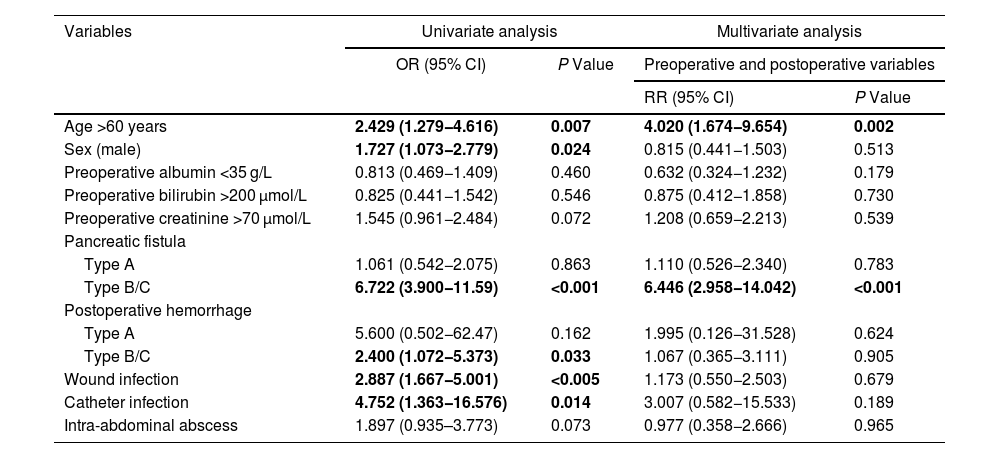

A multivariate model of risk factors was created, including preoperative and postoperative variables (Table 4). The study of risk factors for DGE showed that age over 60 years and pancreatic fistula were risk factors for DGE.

Variables related with delayed gastric emptying.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | Preoperative and postoperative variables | ||

| RR (95% CI) | P Value | |||

| Age >60 years | 2.429 (1.279−4.616) | 0.007 | 4.020 (1.674−9.654) | 0.002 |

| Sex (male) | 1.727 (1.073−2.779) | 0.024 | 0.815 (0.441−1.503) | 0.513 |

| Preoperative albumin <35 g/L | 0.813 (0.469−1.409) | 0.460 | 0.632 (0.324−1.232) | 0.179 |

| Preoperative bilirubin >200 μmol/L | 0.825 (0.441−1.542) | 0.546 | 0.875 (0.412−1.858) | 0.730 |

| Preoperative creatinine >70 μmol/L | 1.545 (0.961−2.484) | 0.072 | 1.208 (0.659−2.213) | 0.539 |

| Pancreatic fistula | ||||

| Type A | 1.061 (0.542−2.075) | 0.863 | 1.110 (0.526−2.340) | 0.783 |

| Type B/C | 6.722 (3.900−11.59) | <0.001 | 6.446 (2.958−14.042) | <0.001 |

| Postoperative hemorrhage | ||||

| Type A | 5.600 (0.502−62.47) | 0.162 | 1.995 (0.126−31.528) | 0.624 |

| Type B/C | 2.400 (1.072−5.373) | 0.033 | 1.067 (0.365−3.111) | 0.905 |

| Wound infection | 2.887 (1.667−5.001) | <0.005 | 1.173 (0.550−2.503) | 0.679 |

| Catheter infection | 4.752 (1.363−16.576) | 0.014 | 3.007 (0.582−15.533) | 0.189 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 1.897 (0.935–3.773) | 0.073 | 0.977 (0.358−2.666) | 0.965 |

Bold values: statistically significant.

The presence of intra-abdominal complications has been related to DGE.1,20 In a previously published randomized study, our group demonstrated that two preoperative variables, hyperbilirubinemia and hypoalbuminemia, were involved in DGE.14 An additional unpublished study of this randomized clinical trial also demonstrated advanced age as a risk factor for DGE. Thus, we must carefully assess patients before performing pancreatic surgery on them.

In 2016, Noorani et al. published an analysis of risk factors for DGE after pancreatic surgery that correlated advanced age (>72 years) with DGE.21 Subsequently, in a review of more than 10 000 patients, Ellis et al.12 demonstrated that age over 75 years was a risk factor for DGE in the absence of pancreatic fistula or intra-abdominal infection (P = 0.003). In our experience, patients over 60 years of age had a higher incidence of DGE. Coinciding with our results, a recent study concluded that age is related to the risk of DGE after PD.13 This study analyzed the risk factors for this complication with a retrospective cohort of 10 249 patients from a national database (The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program), and age over 65 proved to be a risk factor in the multivariate analysis. Some authors have reported affected fundic activity in elderly patients when ingesting liquids,22 which can be correlated with our clinical finding. Thus, in our opinion, pancreatic surgery in elderly patients can be indicated on a personalized basis, taking into account that advanced age is a factor that may lead to greater associated morbidity. However, retrospective studies have ruled out advanced age as a relevant factor in the appearance of DGE.1,23,24 Clearly, there is no consensus regarding the role of age in DGE, which is why it is a datum that should be confirmed in subsequent studies.

The relationship between the presence of pancreatic fistula and DGE is well known,1,2,4,25 as gastric motility is affected by nearby peripancreatic inflammation and sepsis. This is attributed to the detrimental effect of the pancreatic juices on gastric motility.25 In this context, antecolic reconstruction of the gastroenteroanastomosis has demonstrated benefits in terms of DGE, by physically separating the gastric and pancreatic sutures.25 The presence of intra-abdominal abscess after PD has been related to DGE.1,2,20 It has even been shown that the presence of infectious complications is a risk factor for DGE.2,20 However, other infectious complications, such as wound infection, have been less studied in relation to DGE. The Parmar et al.2 article demonstrates that, in addition to sepsis or septic shock, surgical wound dehiscence correlates with DGE. In our series, we have also found that various infectious complications, such as wound infection, catheter infection, or intra-abdominal abscess could worsen digestive transit since they have been more frequent in the group with slow gastric emptying, despite not demonstrating statistical significance in the multivariate analysis.

With regards to infectious complications, various germs have been correlated with postoperative complications after PD. Thus, the isolation of some has been suggested to be the cause, and not the consequence, of the complication, a hypothesis that is difficult to understand, but which is taking shape. In this context, some authors have shown that the identification of Enterococcus faecium in surgical drain discharge is significantly associated with pancreatic fistula. These authors hypothesize that this germ could facilitate the degradation of collagen near the pancreatic suture and favor the formation of pancreatic fistula.26 In a recent study, Coppola et al.27 analyzed the microbiology of the bile duct during surgery. They demonstrated that the isolation of Escherichia coli was associated with greater DGE as a single complication. These authors point out that Escherichia coli can produce and/or consume neurotransmitters, including gamma-aminobutyric acid, the main neurotransmitter inhibitor of intestinal motility and gastric emptying. Coppola et al. defend that the presence of Escherichia coli could imply gastric malfunction.27 Regarding wound infection and its implications, Fong et al.28 recommend systematic intraoperative cultures of the bile obtained. In their study, these authors demonstrate a relationship between the germs obtained from the intraoperative bile cultures and the germs that caused wound infection. We do not have a clear explanation to explain the correlation between wound infection and delayed gastric emptying, but hypothetically it is suggested that the presence of certain germs in the surgical wound could worsen or cause delayed gastric emptying. A detailed study of the contaminating microbiological flora in each of the infectious complications and the impact on gastric emptying would be a subject of interest for future studies.

LimitationsThe main limitation of this study is the lack of analysis of the microbial flora present in the infections registered and the lack of information about the severity of the wound infections. Another limitation is the retrospective analysis of a prospective database, which always reduces the scientific value of the study.

In conclusion, pancreatic fistula is confirmed as a risk factor for DGE after PD. In addition, our study demonstrates that age over 60 is a risk factor for DGE.

We would like to thank the Fundación IDIBELL and the Programa CERCA/Generalitat de Catalunya for their institutional support.