The benefit of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) with superior mesenteric-portal vein resection (PVR) for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PA) is still controversial in terms of morbidity, mortality and survival. We conducted a retrospective study to analyse outcomes of PD with PVR in a Spanish tertiary centre.

MethodsBetween 2002 and 2012, 10 patients underwent PVR (PVR+ group) and 68 standard PD (PVR− group). Morbidity, mortality, overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were compared between PVR+ and PVR− group. Prognostic factors were identified by a Cox regression model.

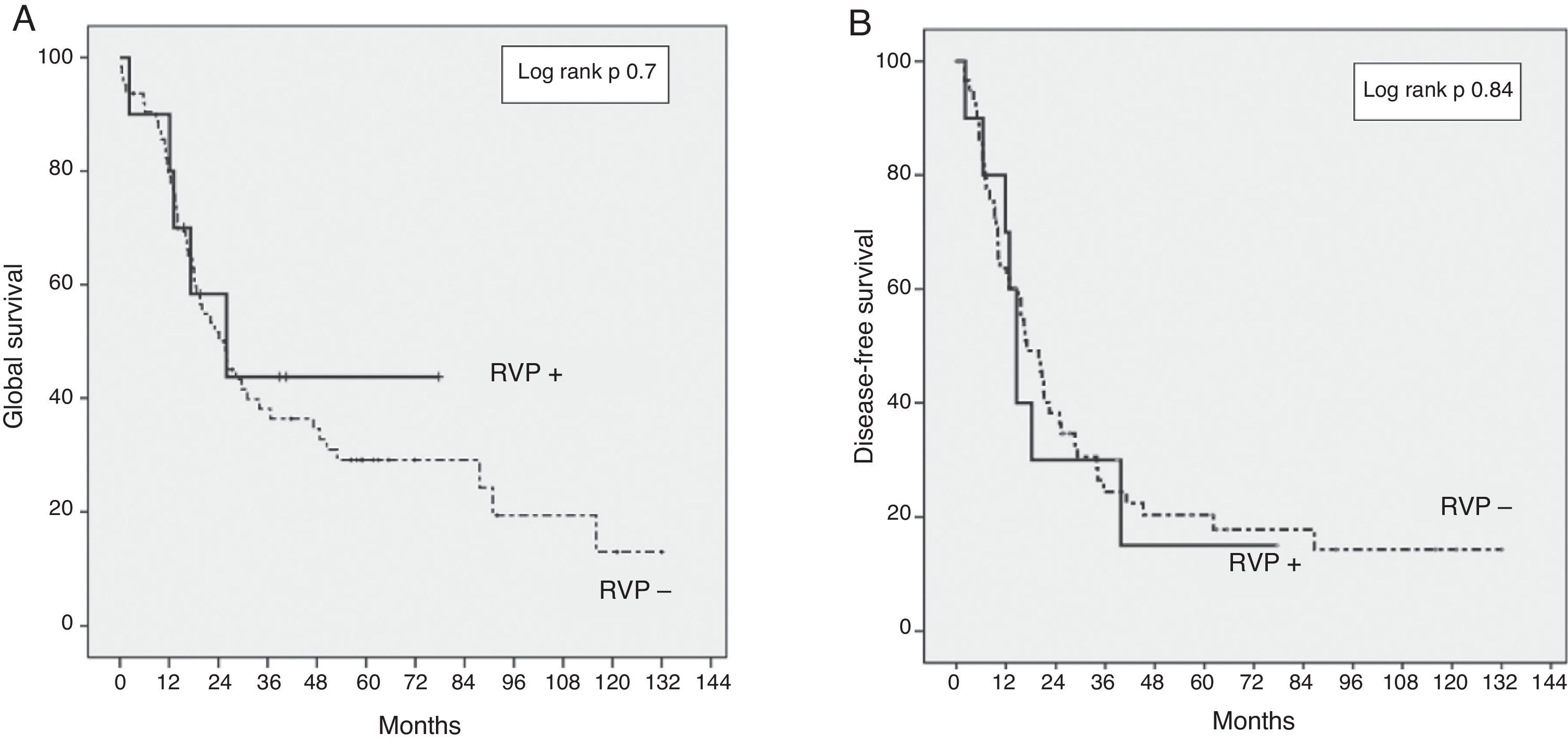

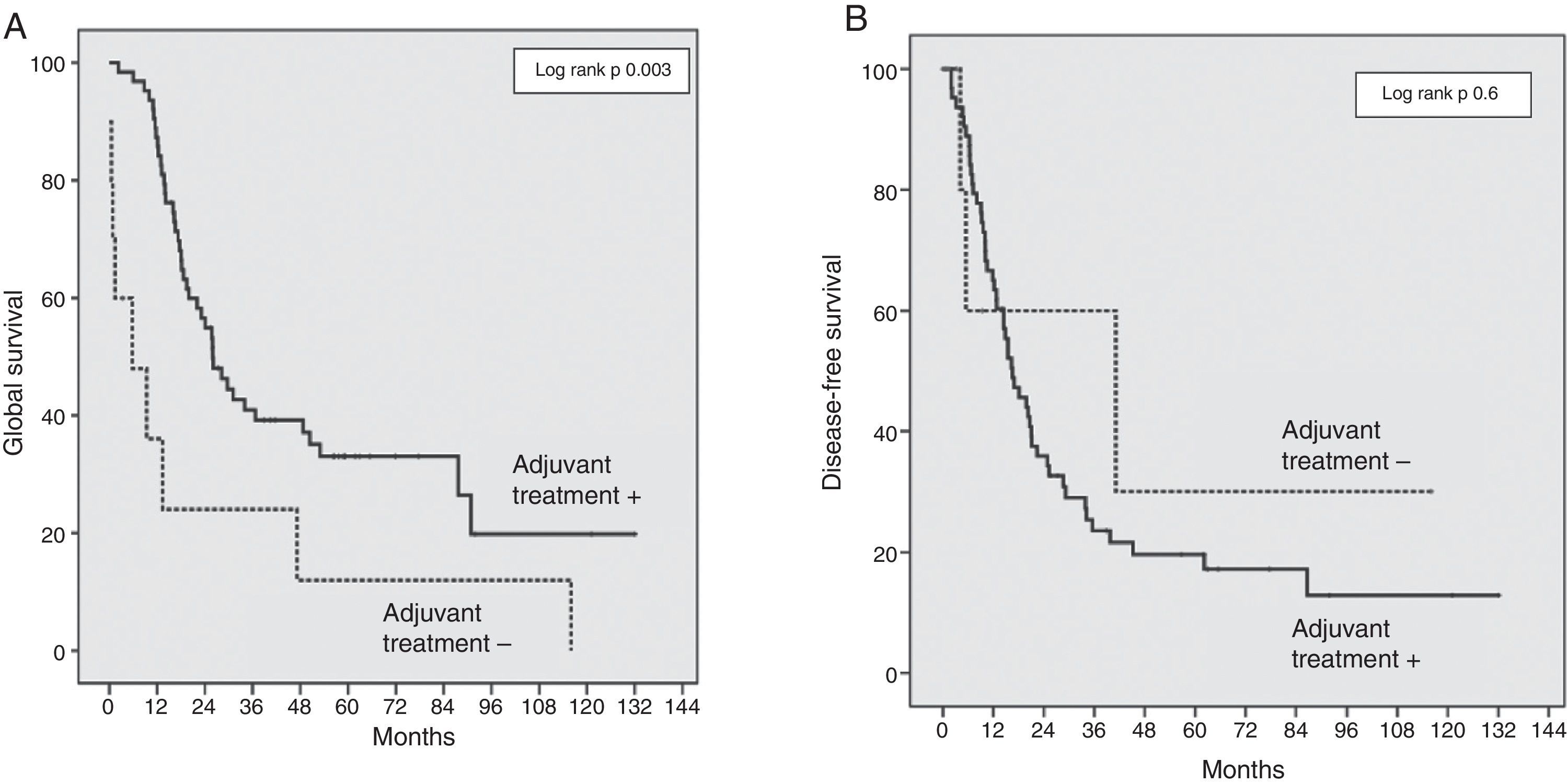

ResultsPostoperative mortality was 5% (4/78), all patients in PVR− group. Morbidity was higher in the PVR− group compared to PVR+ (63% vs 30%, P=.004). OS at 3 and 5 years was 43% and 43% in PVR+ group, 35% and 29% in PVR− group (P=.07). DFS at 3 and 5 years DFS were 28% and 15% in PVR+ group, 25% and 20% in PVR− group (P=.84). Median survival was 23.1 months in PVR− group, and 22.8 months in PVR+ group (P=.73). Factors related with OS were absence of adjuvant treatment (OR 2.9, 95%IC: 1.39–6.14, P=.003), R1 resection (OR 2.3, 95%IC: 1.2–4.43, P=.006), preoperative CA 19.9 level ≥ 170UI/mL (OR 2.3, 95%IC: 1.22–4.32, P=.01). DFS risk factors were R1 resection (OR 2.6, 95%IC: 1.41–4.95, P=.002); moderate or poor tumour differentiation grade (OR 2.7, 95%IC: 1.23–6.17, P=.01); N1 lymph node status (OR 1.8, 95%IC: 1.02–3.19, P=.04); CA 19.9 level ≥ 170UI/mL (OR 2.4, 95%IC: 1.30–4.54, P=.005).

ConclusionsPVR for PA can be performed safely. Patients with PVR have a comparable survival to patients undergoing standard PD if disease-free margins can be obtained.

El beneficio de la duodenopancreatectomía cefálica (DPC) con resección de la vena mesentérica superior/vena porta (RVP) para el adenocarcinoma de páncreas (ADCP) es controvertido en cuanto a la morbilidad, mortalidad y supervivencia. Se analizan los resultados de la DPC con RVP en un centro terciario español.

MétodosEntre 2002 y 2012, 10 pacientes fueron tratados mediante RVP (RVP+) y 68 con DPC estándar (RVP−). La morbilidad, mortalidad, supervivencia global (SG) y supervivencia libre de enfermedad (SLE) se compararon entre pacientes RVP+/RVP−. Los factores pronósticos fueron identificados con regresión de Cox.

ResultadosLa mortalidad postoperatoria fue del 5% (4/78), todos los pacientes en el grupo RVP−. La morbilidad fue mayor en el grupo RVP− comparado con RVP+ (63 vs. 30%; p = 0,04). La SG a 3 y 5 años fue 43 y 43% en el grupo RVP+, 35 y 29% en RVP− (p = 0,7). La SLE a 3 y 5 años fue 28 y 15% en RVP+, 25 y 20% en RVP− (p = 0,84). La mediana de supervivencia fue de 23,1 meses en el grupo RVP− y de 22,8 meses en el grupo RVP+ (p = 0,73). Los factores relacionados con la SG fueron ausencia de tratamiento adyuvante (OR 2,9; IC95%: 1,39-6,14; p = 0,003), resección R1 (OR 2,3; IC95%: 1,2-4,43; p = 0,006), CA 19.9 ≥ 170 UI/mL (OR 2,3; IC95%: 1,22-4,32; p = 0,01). Los factores de riesgo para SLE fueron resección R1 (OR 2,6; IC95%: 1,41-4,95; p = 0,002); tumores pobremente diferenciados (OR 2,7; IC95%: 1,23-6,17; p = 0,01); tumores N1 (OR 1,8; IC95%: 1,02-3,19; p = 0,04); CA 19.9 ≥ 170 UI/mL (OR 2,4; IC95%: 1,30-4,54; p = 0,005).

ConclusionesLa RVP para ADCP puede realizarse con seguridad. Pacientes con RVP tienen una supervivencia comparable a los pacientes tratados mediante DPC estándar si se obtienen márgenes libres.

A ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head (DAPH) is the fourth cause of death due to cancer in Spain, with approximately 4000 new cases diagnosed every year.1 Cephalic duodenopancreatectomy (CDP) for DAPH is the only potentially curative treatment for this type of aggressive cancer. However, only 10%–20% of these patients are treated with surgery. This is mainly due to the presence of metastatic disease or locally advanced in the form of vascular invasion at the time of the diagnosis.2,3 The long-term results after surgery are still poor, with a global survival at 5 years between 10% and 27%, and with a mean survival between 14 and 33 months in the most recent papers, even with adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (NCRT).4–9 Multimodal oncosurgical therapy has increased the resectability rate, particularly for patients with DAPH classified as borderline.10 An extension of the retroperitoneal tumour usually implies the invasion of the superior mesenteric vein/portal vein (SMV/PV), which, in that case, has to be resected to achieve complete excision (R0), and allow cure.11,12 The long-term survival results of the CDP with venous resection seem, at least, comparable to those of the patients without vascular resection, but the effective benefit of this procedure is still being discussed.13–17

The purpose of this study is to analyse the results of CDP with SMV/PV resection, compared with CDP without venous resection, in a European university hospital.

MethodsSelection of PatientsBetween 2002 and 2012, 252 patients were treated with CDP in our centre. The patient data was registered prospectively in a database. Patients that required pancreatic resection due to a benign disease, with periampullary cancer, distal bile duct cholangiocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumours and intraductal mucinous papillary neoplasm were excluded. A retrospective analysis was performed on 78 CDPs with curative intent for DAPH: 10 patients with SMV/PV resection (PVR+) were compared to 68 patients without venous resection (PVR−). The data registered were: demographic, surgical and pathology data, complications, hospital stay, global survival (GS) and disease-free survival (DFS). The mean follow-up time was 23 months (range: 1–132). The preoperative assessment of the patients consisted of a detailed medical history and a physical exam, CA19-9 levels and a thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT scan). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasound scans with or without tumour biopsy were performed selectively. The Ethics Committee at the Hospital approved the study.

Resectability Criteria, Adjuvant and Neoadjuvant TherapyThe absence of vascular involvement in the images showing <180° invasion of the vein circumference without arterial involvement was accepted as an indication for direct surgery. Distant metastasis, as well as invasion of the celiac artery/superior mesenteric artery (SMA), >180° involvement of the circumference or complete thrombosis of the mesenteric-portal system without reconstructive options established in the preoperative assessment were considered contraindications for surgery.

>180° unilateral or bilateral narrowing of the mesenteric-portal axis, ≤180° contact of the SMA, involvement of a short segment of the hepatic artery (HA) without extension to the celiac artery were considered borderline lesions, with indication for receiving NCRT.18,19 Patients candidate to treatment with NCRT had an endoscopy-guided biopsy performed. These patients received gemcitabine-based or gemcitabine/oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy for 3 months, followed by radiotherapy in the case of exclusion of disease progression. Cancer staging assessments were performed every 4 weeks. External radiation consisted of 50.4Gy combined with 5-fluorouracil or capecitabine; 4–6 weeks after the end of treatment, patients underwent a new multidisciplinary assessment with a CT scan and a physiological assessment to determine operability. Patients were considered fit for surgical intervention in the case of stable disease.

Patients with obstructive jaundice were drained, preferably via endoscopy in the case of surgery delayed longer than 10 days after diagnosis due to diagnostic or therapeutic reasons, in those symptomatic patients (cholangitis, intense pruritus) with alteration of renal function or important cardiovascular comorbidities. Internal biliary drainage was performed with extractable plastic endoprosthesis. A temporary biliary endoprosthesis was systematically placed in those patients who were candidates for NCRT. Internal–external percutaneous radiological drainage was performed very selectively in the case of failure of or contraindications for endoscopic drainage. Surgery was deferred in the case of biliary drainage for 3–6 weeks until the resolution of jaundice in the PVR− group, and until the end of the NCRT protocol in the PVR+ group.

After surgery, patients with risk factors for recurrence (microscopically incomplete resection, involvement of the lymph nodes, perineural or microvascular invasions) were assessed for receiving gemcitabine-based chemotherapy on an individual basis until 2008. In the period that followed, all resected patients were assessed for receiving a gemcitabine-based adjuvant protocol based on their general condition, comorbidities and age.9,20

Surgical TechniqueA team of three expert surgeons performed all the procedures. CDP with pylorus preservation is the most common procedure in our centre. We performed a standard lymphadenectomy of the periduodenal and pancreatic head with a dissection of the hepatic pedicle and common HA, exeresis of the retroportal pancreatic lamina and the lymphatic tissue located on the right side of the SMA, without the extended lymphadenectomy described by other authors.21,22 A duct-mucosal pancreaticojejunostomy was systematically performed with a catheter of a diameter adapted to the Wirsung duct, externalised through the wall of the jejunal loop. An end-to-side hepaticojejunostomy was performed at 20–30cm distal to the same jejunal segment; an end-to-side gastrojejunostomy was performed 30cm distal to the same loop, preferably in an antecolic manner. Patients with a DAPH with invasion of the mesenteric-portal system were treated with retroperitoneal dissection, followed by a pancreatic, biliary and digestive section. All the digestive sections were performed before the vascular resection. In the case of >2cm segmental resection, the root of the mesentery was moved before vascular clamping to facilitate reconstruction without tension. When the SMV/PV confluence with the splenic vein was resected, the axial continuity was first restored, and then a splenic vein retransplantation was performed under lateral clamping only in the case of inferior mesenteric vein drainage in the SMV/PV.

Postoperative Mortality and MorbidityPostoperative morbidity and mortality defines the events that occur in the 90 days following surgery. Complications are classified according to Dindo-Clavien (DC). Severe complications were defined as ≥ grade III.23 The definitions of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery were applied for pancreatic fistula, haemorrhage and delayed gastric emptying.24–26

Pathology AssessmentTumours are classified according to the AJCC-TNM system. Pathological findings include tumour size, differentiation, perineural, microvascular and lymphatic metastasis. Margins are defined as pancreatic (neck of pancreas section), biliary (bile duct section), and radial (retroperitoneal margin). A resection margin lower than 1mm was considered invaded (R1).

Statistical AnalysisContinuous variables were compared using the Student's T test. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi Square test. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the patients’ GS and DFS, compared against the log-rank test. The factors related to survival were analysed with the Cox proportional hazards model. A value of P<.05 was considered significant. The analyses were performed using the SPSS programme, version 15.0.

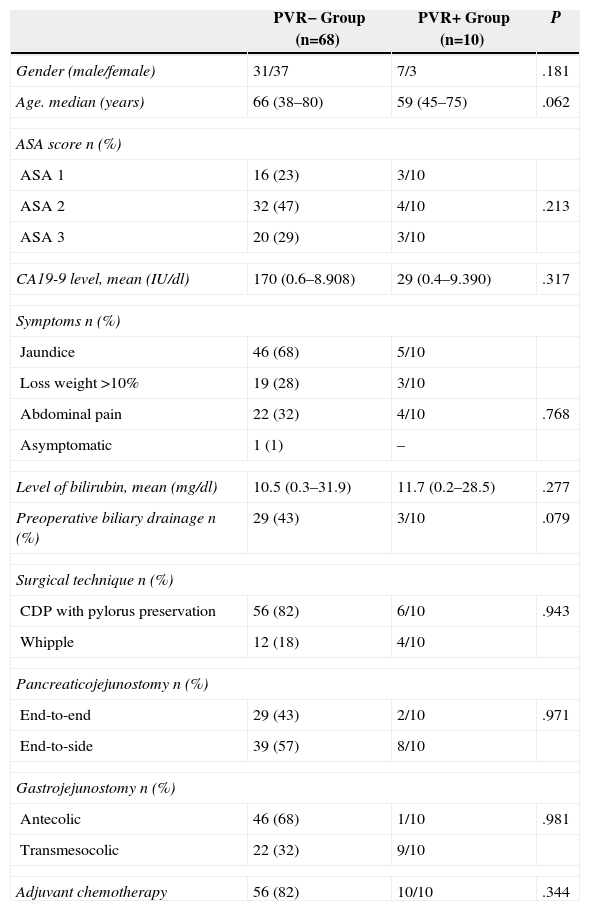

ResultsDuring the study period, the data for 78 patients was analysed. Ten patients from the PVR+ group were compared with the 68 patients in the PVR− group. The patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. Out of the 68 patients in the PVR− group, 29 (43%) presented jaundice with an indication of preoperative biliary drainage: 22 of them were drained with endoscopic plastic endoprosthesis and seven patients received internal-external transhepatic percutaneous radiological drainage. Three patients from the PVR+ group received NCRT: gemcitabine-capecitabine in two cases and gemcitabine-oxaliplatin-5-fluorouracil in one case. All of them had a preoperative endoscopic biliary drainage performed with a plastic prosthesis. Among the patients in the PVR+ group, the preoperative CT scan detected vascular infiltration in four; extrinsic compression in two; <180° narrowing of the vein circumference in two; >180° stenosis in two; and one patient had an SMA° contact of <180. Lateral vein resections were performed in four patients and segmental ones in six. The median length was 2.1cm (1–3cm). Re-implantation of the splenic vein was performed on two patients. The median duration of the mesenteric-portal system clamping was 26min (20–55min). The median operating time in the PVR+ group was 355min (240–510min), with median haematic losses of 700cc (200–3500cc).

Demographic and Operative Data.

| PVR− Group (n=68) | PVR+ Group (n=10) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 31/37 | 7/3 | .181 |

| Age. median (years) | 66 (38–80) | 59 (45–75) | .062 |

| ASA score n (%) | |||

| ASA 1 | 16 (23) | 3/10 | |

| ASA 2 | 32 (47) | 4/10 | .213 |

| ASA 3 | 20 (29) | 3/10 | |

| CA19-9 level, mean (IU/dl) | 170 (0.6–8.908) | 29 (0.4–9.390) | .317 |

| Symptoms n (%) | |||

| Jaundice | 46 (68) | 5/10 | |

| Loss weight >10% | 19 (28) | 3/10 | |

| Abdominal pain | 22 (32) | 4/10 | .768 |

| Asymptomatic | 1 (1) | – | |

| Level of bilirubin, mean (mg/dl) | 10.5 (0.3–31.9) | 11.7 (0.2–28.5) | .277 |

| Preoperative biliary drainage n (%) | 29 (43) | 3/10 | .079 |

| Surgical technique n (%) | |||

| CDP with pylorus preservation | 56 (82) | 6/10 | .943 |

| Whipple | 12 (18) | 4/10 | |

| Pancreaticojejunostomy n (%) | |||

| End-to-end | 29 (43) | 2/10 | .971 |

| End-to-side | 39 (57) | 8/10 | |

| Gastrojejunostomy n (%) | |||

| Antecolic | 46 (68) | 1/10 | .981 |

| Transmesocolic | 22 (32) | 9/10 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 56 (82) | 10/10 | .344 |

ASA score: American Society of Anaesthesiology; CA19-9: carbohydrate antigen 19.9; DPCPP: cephalic duodenopancreatectomy with pylorus preservation.

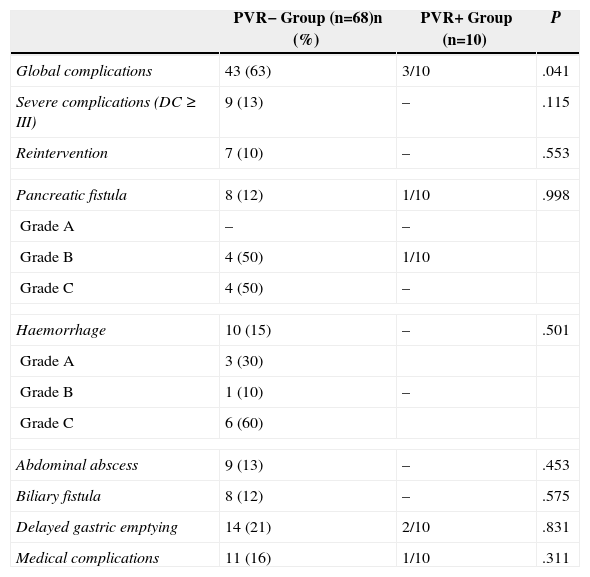

Postoperative complications are shown in Table 2. Global morbidity was higher in the PVR− group. Nine patients (13%) from the PVR− group had grade III–IV complications: Seven patients required further intervention (five due to haemorrhage related to a pancreatic fistula, one due to abdominal abscess debridement and another one due to choleperitoneum), one patient had radiological drainage of abdominal abscess and another one arterial embolisation. None of the patients in the PVR+ group had severe complications. Hospitalisation was significantly longer in the PVR− group than in the PVR+ group (23±14 against 15±6 days; P=.02). Global mortality was 5% (4/78); all the patients in the PVR− group as a consequence of a grade C pancreatic fistula.

Postoperative Complications.

| PVR− Group (n=68)n (%) | PVR+ Group (n=10) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global complications | 43 (63) | 3/10 | .041 |

| Severe complications (DC ≥ III) | 9 (13) | – | .115 |

| Reintervention | 7 (10) | – | .553 |

| Pancreatic fistula | 8 (12) | 1/10 | .998 |

| Grade A | – | – | |

| Grade B | 4 (50) | 1/10 | |

| Grade C | 4 (50) | – | |

| Haemorrhage | 10 (15) | – | .501 |

| Grade A | 3 (30) | ||

| Grade B | 1 (10) | – | |

| Grade C | 6 (60) | ||

| Abdominal abscess | 9 (13) | – | .453 |

| Biliary fistula | 8 (12) | – | .575 |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 14 (21) | 2/10 | .831 |

| Medical complications | 11 (16) | 1/10 | .311 |

DC: Dindo-Clavien classification.

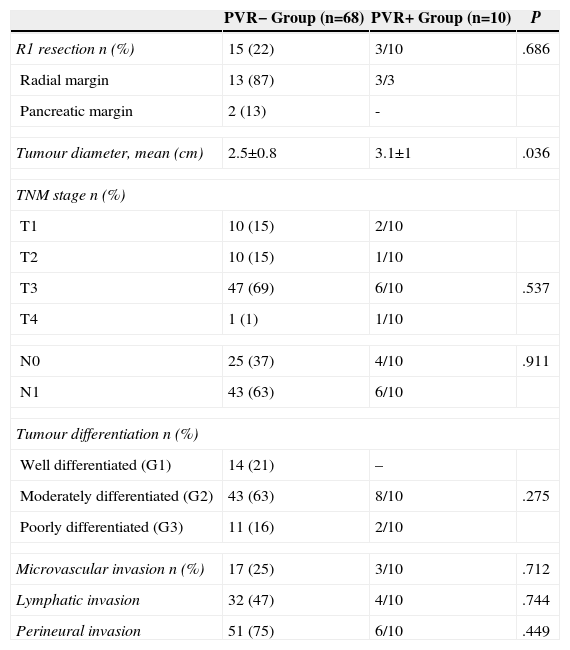

The pathological characteristics are summarised in Table 3. Three R1 resections were performed in the PVR+ group and 15 (22%) in the PVR− group (P=.68). In most cases, the radial margin was involved. The tumour diameter was significantly higher in the PVR+ group than in the PVR− group (3.1±1 as against 2.5±0.8cm; P=.03).

Pathological Findings.

| PVR− Group (n=68) | PVR+ Group (n=10) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 resection n (%) | 15 (22) | 3/10 | .686 |

| Radial margin | 13 (87) | 3/3 | |

| Pancreatic margin | 2 (13) | - | |

| Tumour diameter, mean (cm) | 2.5±0.8 | 3.1±1 | .036 |

| TNM stage n (%) | |||

| T1 | 10 (15) | 2/10 | |

| T2 | 10 (15) | 1/10 | |

| T3 | 47 (69) | 6/10 | .537 |

| T4 | 1 (1) | 1/10 | |

| N0 | 25 (37) | 4/10 | .911 |

| N1 | 43 (63) | 6/10 | |

| Tumour differentiation n (%) | |||

| Well differentiated (G1) | 14 (21) | – | |

| Moderately differentiated (G2) | 43 (63) | 8/10 | .275 |

| Poorly differentiated (G3) | 11 (16) | 2/10 | |

| Microvascular invasion n (%) | 17 (25) | 3/10 | .712 |

| Lymphatic invasion | 32 (47) | 4/10 | .744 |

| Perineural invasion | 51 (75) | 6/10 | .449 |

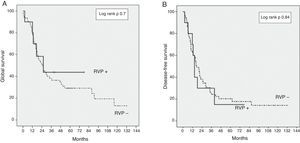

The GS for the entire series was 37% and 30% at three and five years, respectively. The GS at three and five years in the PVR+ group was 43% and 43% respectively, compared with 35% and 29% in the PVR− group (P=.7) (Fig. 1). The DFS at three and five years in the PVR+ group was 28% and 15% respectively, without significant differences compared with the PVR− group: 25% and 20% at three and five years (P=.84). The median survival was 23.1 months in the PVR− group and 22.8 months in the PVR+ group (P=.73).

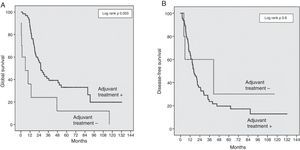

The risk factors analysed for survival and recurrence were: age, gender, preoperative levels of bilirubin and CA19-9 levels, global morbidity, R0/R1, resection, SMV/PV resection, tumour diameter and differentiation, cancer stage (T/N), perineural, lymphatic and microvascular invasion, and absence of adjuvant treatment. The factors associated with a lower GS were an absence of co-adjuvant treatment (OR 2.9; IC 95%: 1.39–6.14; P=.003), R1 resection (OR 2.3; IC 95%: 1.27–4.43; P=.006), preoperative CA19-9 levels ≥170 UI/mL (OR 2.3; IC 95%: 1.22–4.32; P=.01). The risk of recurrence was also associated with a R1 resection (OR 2.6; IC 95%: 1.41–4.95; P=.002); moderate or poorly differentiated tumours (OR 2.7; IC 95%: 1.23–6.17; P=.01); N1 stage (OR 1.8; IC 95%: 1.02–3.19; P=.04) and CA19-9 levels ≥170 UI/mL (OR 2.4; IC 95%: 1.30–4.54; P=.005). The absence of adjuvant treatment was the most important survival risk factor in our series, although without any influence on the DFS (Fig. 2).

DiscussionMoore described CDP with SMV/PV resection for DAPH for the first time in 1951, but the first series of 18 patients was published in 1977, with a mortality rate of 17% at 30 days.27 The first studies reported very poor survival results. The studies included venous as well as arterial resections, with elevated morbidity. Thanks to the greater accessibility of test research, better indications have been defined and the SMV/PV resection has become a well-established procedure with long-term results comparable to those of the standard CDPs, without an increase in morbidity in an expert environment.14,16 Our sample shows the safety and feasibility of the procedure, with a global morbidity comparable to that in the existing research, varying between 16% and 54%.15

Our sample has shown a rate of complications in the PVR+ group significantly lower than that of the standard CDP (63% vs 30%; P=.04), although the rate of severe complications does not differ between both groups (13% vs 0%; P=.11). The lower proportion of global morbidity in the PVR+ group, although caused by minor complications (DC grade I and II), could be partly explained as a temporary effect, since patients in this group have received intervention in more recent years compared to those of the PVR− group, with a relative increase in the experience of the surgical team.

We reported a global mortality at 90 days of 5%, without death in the PVR+ group. The perioperative mortality for CDP by DAPH was between 2.9% and 7.7% in research with no difference recorded between CDP and CDP with venous resection.13,15,16 On the contrary, a recent meta-analysis of 3582 CDPs (7.8% with venous resection, n=281), recorded a higher mortality rate at 30 days for the CDP with SMV/PV resection, in comparison with the standard CDP: 5.7% versus 2.9%, respectively (P=.008); a higher global morbidity rate was also reported: 39.9% versus 33.3%, respectively (P=.02).17

In our series, we have used the NCRT in patients with borderline lesions and gemcitabine-based adjuvant chemotherapy, as described in the literature.9,20 We reported a GS in the PVR+ group of 43% at three years, versus 35% in the PVR− group (P=.7) (Fig. 1). The GS at five years is equally higher in the PVR+ group (43%) in comparison with the PVR− group (29%). Even though this survival difference is not significant, this relative GS increase could be a reflection of the higher proportion of patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy in the PVR+ group. Even without significant differences, only 82% of the patients in the PVR− group received adjuvant treatment, compared to 100% of the PVR+ patients. However, the adjuvant chemotherapy in our sample is a determinant GS factor, although without effect on the DFS (Fig. 2).

The DFS at three years in the PVR+ group was 28%, compared to 25% in the PVR− group (P=.84) (Fig. 1). This data is consistent with the recent data for this disease.16 No randomised controlled trials have been performed yet to assess the benefits of NCRT versus surgery in borderline pancreatic cancer. Notwithstanding, retrospective studies have demonstrated the efficiency of NCRT in this context in terms of (1) increase of resectability, (2) sparing unnecessary surgery in the case of progression during treatment and (3) delay in adjuvant treatment due to complications.28–31 The main risk factor independently associated with survival in our series is the lack of adjuvant treatment, which confirms the essential role of chemotherapy in the treatment of DAPH.5,9,32 R1 resection was associated with a lower survival rate and a greater risk of recurrence. Complete resection is the determinant factor for the prognosis of this disease and the only way to achieve healing.2,4,6,9,11,22,32 We found CA19-9 levels to have significant prognostic value: a preoperative marker level above 170U/ml is associated with a higher risk of recurrence and lower survival rates. Other studies identified a CA19-9 serum level above 370U/ml as a prognostic factor at any stage of DAPH and also as a marker of the response to chemotherapy.33,34

The main limitation of this study is the size of the sample studied and its retrospective nature. The results described have to be interpreted with caution. Despite the fact that the number of patients in this study is limited, we demonstrated the safety of CDP with a venous resection in the DAPH in a third level Spanish centre. The results of our initial experience demonstrate the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in a complex oncologic disease and the need to prepare a multimodal strategy to guarantee a better survival for the patient. In our experience, the GS and DFS of the CDP with a venous resection are comparable to those of the standard CDP in selected patients. For this reason, in the case of invasion of the SMV/PV axis, vascular resection has to be taken into account every time in the absence of other contraindications, provided that a complete tumour resection can be performed.

Authorship/collaboratorsFilippo Landi: Design, data gathering, acquisition and interpretation. Critical review and final version approval.

Cristina Dopazo: Design, data gathering, acquisition and analysis. Critical review and approval of the final version.

Gonzalo Sapisochin: Data gathering and interpretation. Critical review and final version approval.

Marc Beisani: Data gathering and interpretation. Critical review and final version approval.

Laia Blanco: Data gathering and interpretation. Critical review and final version approval.

Mireia Caralt: Data gathering and interpretation. Critical review and final version approval.

Joaquim Balsells: Design, data acquisition and interpretation, article drafting. Critical review and final version approval.

Ramón Charco: Design, data interpretation. Critical review and final version approval.

Conflict of InterestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Landi F, Dopazo C, Sapisochin G, Beisani M, Blanco L, Caralt M, et al. Resultados a largo plazo de la duodenopancreatectomía cefálica con resección de la vena mesentérica superior y vena porta por adenocarcinoma de la cabeza de páncreas. Cir Esp. 2015;93:522–529.