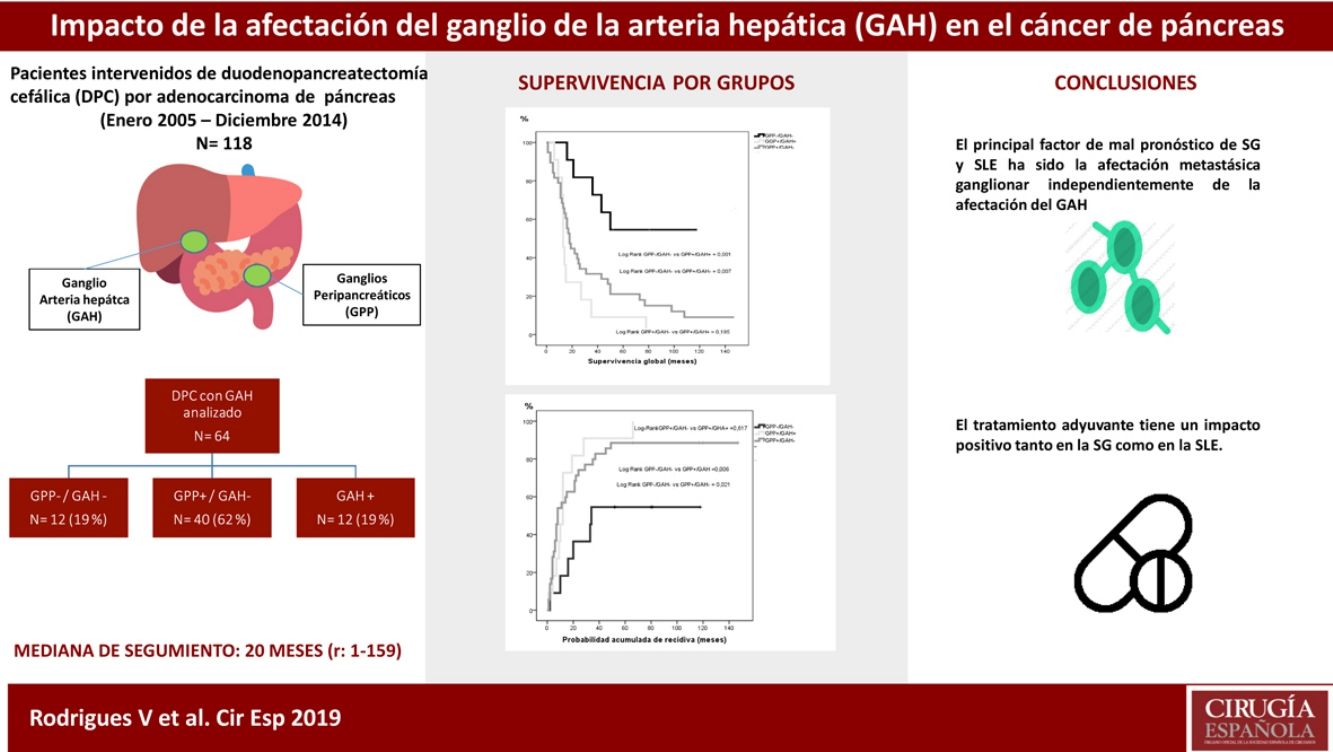

The aim of this study is to analyze the impact of hepatic artery lymph node (HALN) involvement on the survival of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PA).

MethodsA single-center retrospective study analyzing patients who underwent PD for PA. Patients were included if, during PD, the HALN was submitted for pathologic evaluation. Patients were stratified by node status: PPLN− (peripancreatic lymph node)/HALN−, PPLN+/HALN− and PPLN+/HALN+. Survival analysis was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and Cox regression was used for risk factors analyses.

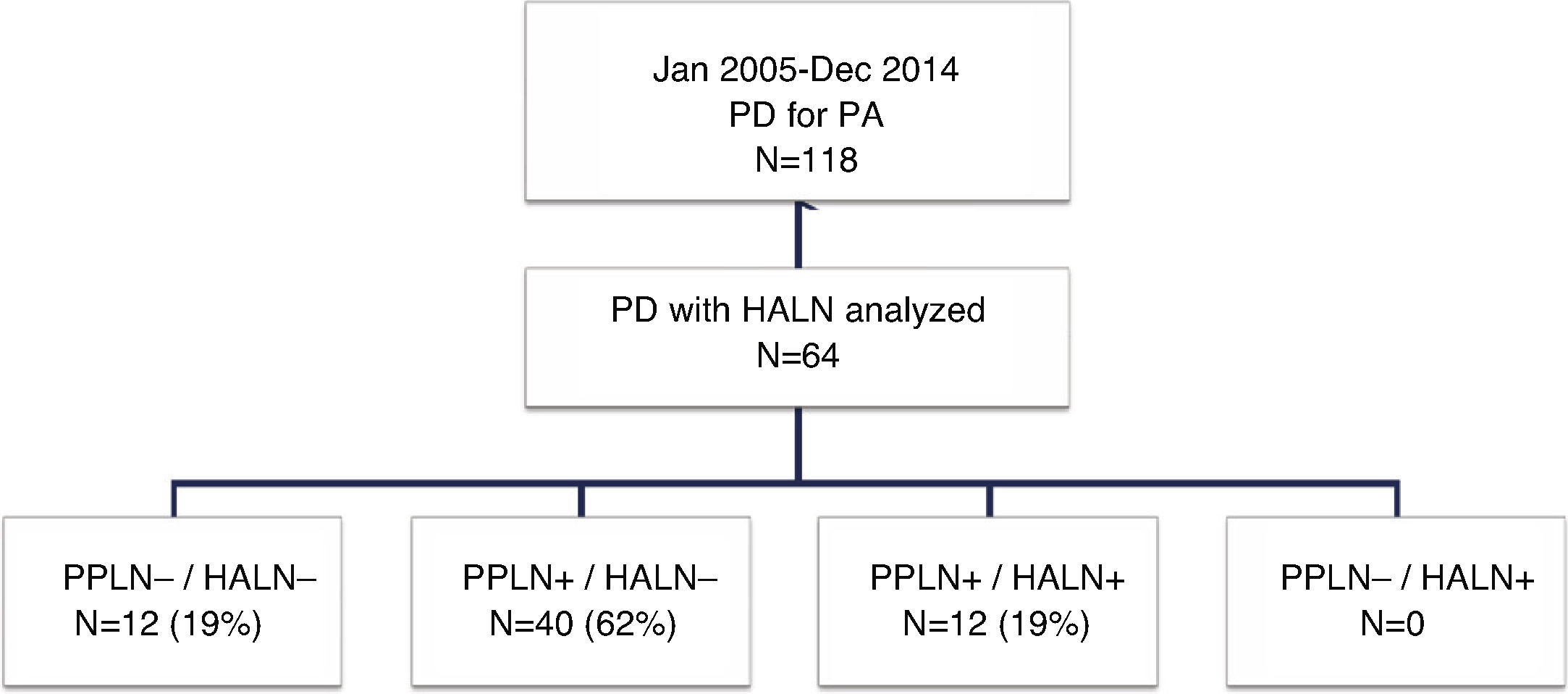

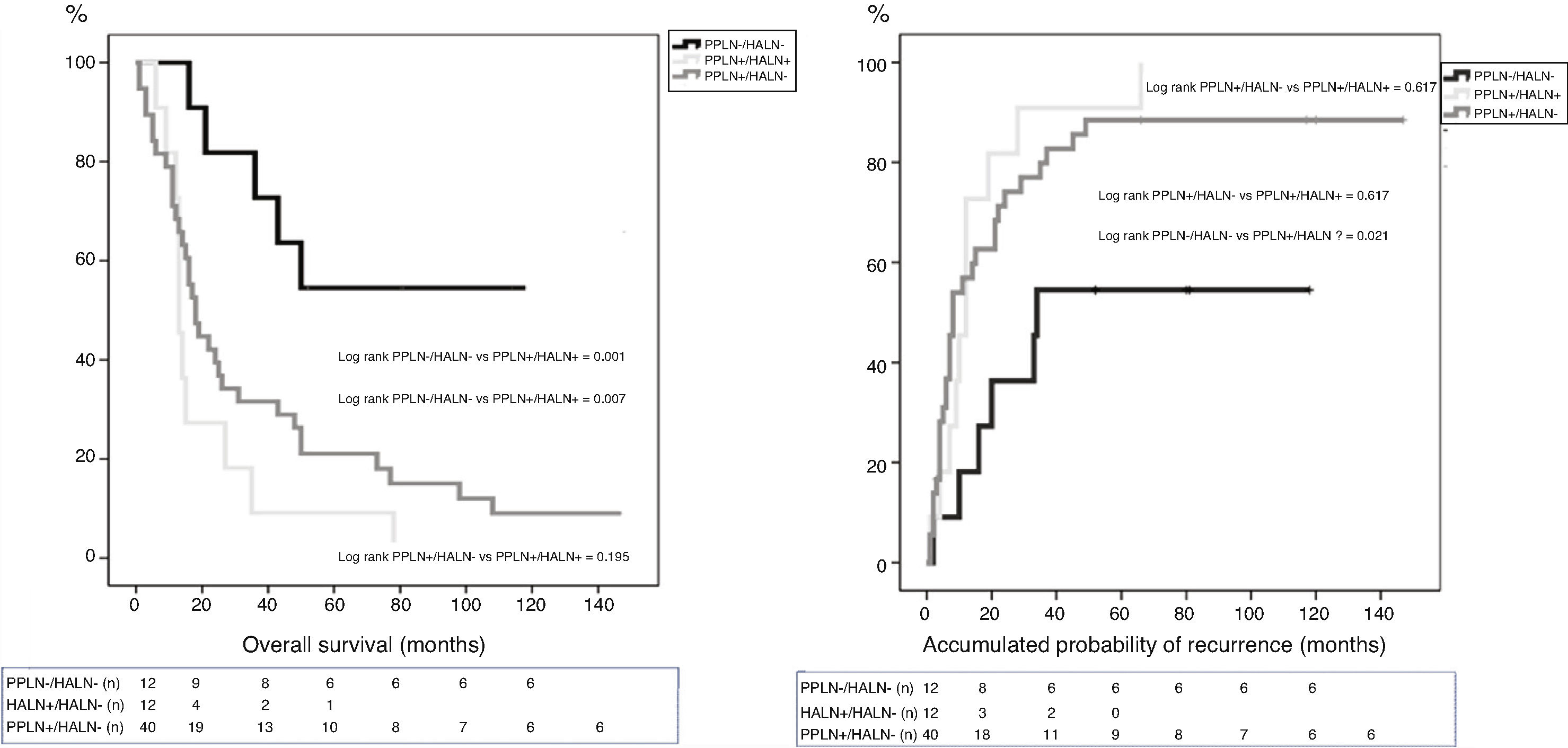

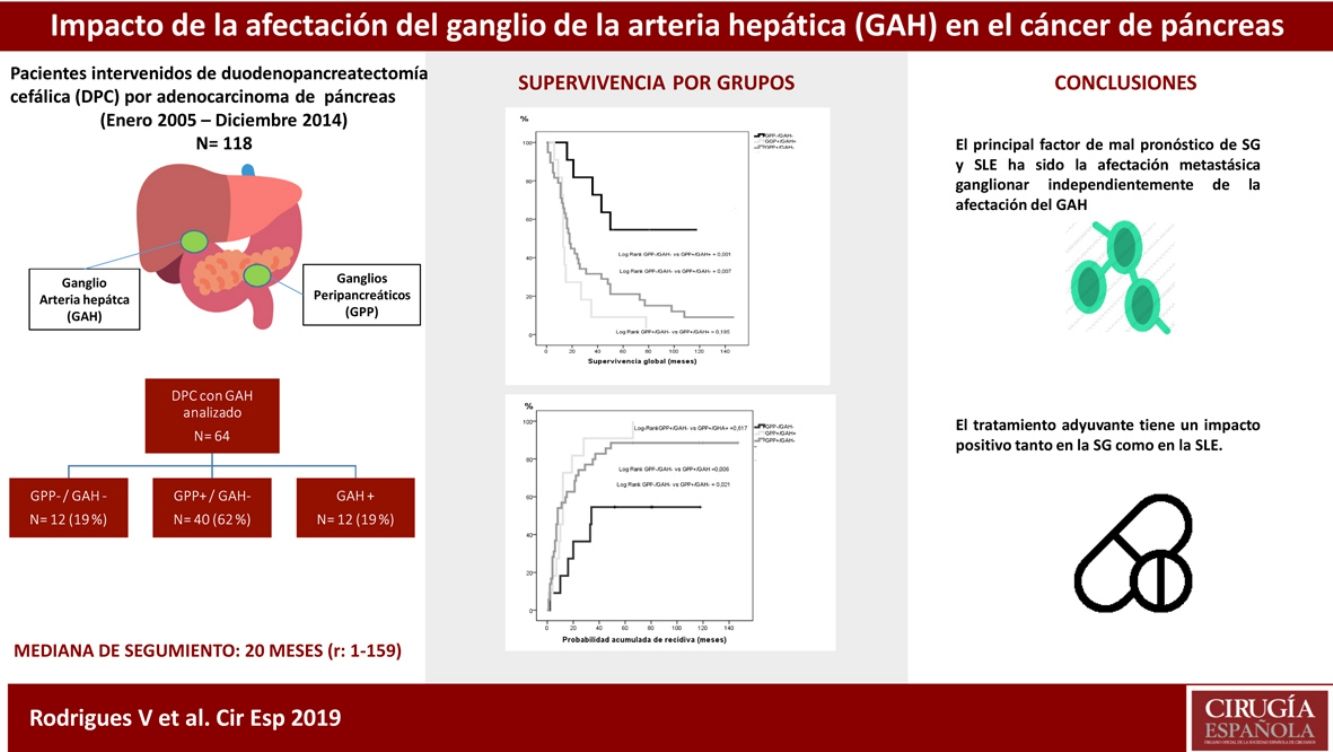

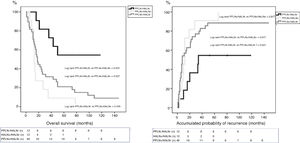

ResultsOut of the 118 patients who underwent PD for PA, HALN status was analyzed in 64 patients. The median follow-up was 20months (r: 1–159months). HALN and PPLN were negative in 12patients (PPLN−/HALN−, 19%), PPLN was positive and HALN negative in 40patients (PPLN+/HALN−, 62%), PPLN and HALN were positive in 12 patients (PPLN+/HALN+, 19%) and PPLN was negative and HALN positive in 0 patients (PPLN−/HALN+, 0%). The overall 1, 3 and 5-year survival rates were statistically better in the PPLN−/HALN− group (82%, 72%, 54%) than in the PPLN+/HALN− group (68%, 29%, 21%) and the PPLN+/HALN+ group (72%, 9%, 9%, respectively) (P=.001 vs P=.007). The 1, 3 and 5-year probabilities of cumulative recurrence were also statistically better in the PPLN−/HALN− group (18%, 46%, 55%) than in the PPLN+/HALN− group (57%, 80%, 89%) and the PPLN+/HALN+ group (46%, 91%, 100%, respectively) (P=.006 vs P=.021). In the multivariate model, the main risk factor for overall survival and recurrence was lymphatic invasion, regardless of HALN status.

ConclusionsIn pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients with lymph node disease, survival after PD is comparable regardless of HALN status.

El objetivo del presente estudio es analizar el impacto de la afectación del ganglio de la arteria hepática (GAH) en la supervivencia de los pacientes intervenidos de duodenopancreatectomía cefálica (DPC) por adenocarcinoma (ADK) de cabeza de páncreas.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo unicéntrico de pacientes intervenidos de DPC por ADK de cabeza de páncreas, con estudio anatomopatológico independiente del GAH. Los pacientes se agruparon en: 1)pacientes sin afectación del GAH ni ganglios peripancreáticos (GGP) (GPP−/GAH−); 2)pacientes con afectación ganglionar peripancreática (GPP+/GAH−), y 3)pacientes con afectación ganglionar peripancreática y de la arteria hepática (GGP+/GAH+). Para el análisis de supervivencia se utilizaron las curvas Kaplan-Meier. Los factores pronósticos de supervivencia global (SG) y libre de enfermedad (SLE) fueron identificados mediante el análisis de regresión de Cox.

ResultadosEntre enero de 2005 y diciembre de 2014 se intervinieron 118 pacientes, y el GAH fue analizado en 64 de ellos. La mediana de seguimiento fue de 20meses (r: 1-159meses). La distribución por grupos fue la siguiente: GPP−/GAH− en 12 (19%), GPP+/GAH− en 40 (62%), GGP+/GAH+ en 12 (19%) y CGP-/CGH+ en 0 (0%), La SG a 1, 3 y 5años fue estadísticamente mejor en el grupo GPP−/GAH− (82, 72 y 54%) comparado con GPP+/GAH− (68, 29 y 21%) y GGP+/GAH+ (72, 9 y 9%) (p=0,001 vs p=0,007). La probabilidad acumulada de recidiva a 1, 3 y 5años fue estadísticamente inferior en el grupo GPP−/GAH− (18, 46 y 55%) comparado con el grupo GPP+/GAH− (57, 80 y 89%) y grupo GGP+/GAH+ (46, 91 y 100%) (p=0,006 vs p=0,021). En el análisis multivariante el principal factor de riesgo tanto de SG como de SLE fue la invasión linfática independientemente del estado del GAH.

ConclusionesNuestros resultados sugieren que la afectación adenopática impacta en la supervivencia del ADK de páncreas sin poder identificar la afectación del GAH como marcador pronóstico.

Pancreatic cancer is the seventh leading cause of cancer death in industrialized countries. According to GLOBOCAN 2018 estimates, pancreatic cancer has been ranked as the eleventh most common cancer in the world, with 458918 new cases per year and 432242 deaths. Spain has an estimated 7279 deaths, with an incidence of 7765 cases in 2018.1 Surgical resection is the only potentially curative treatment,2 but only 20% of patients are candidates for this treatment, with a 5-year survival rate that does not exceed 30%.3

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is a complex operation that has an associated mortality rate of 2.1%–10.3%4 and a morbidity rate of 65%–69%.5 This high morbidity and mortality could be avoided in those patients in whom surgery would not benefit survival, if they could be identified preoperatively. Various prognostic factors have been described in pancreatic cancer, such as tumor size, histopathological grade, vascular invasion, perineural invasion, involvement of the resection margins, and lymph node involvement,6 the latter being one of the main factors for a poor prognosis in patients treated surgically with curative intent.7 The common hepatic artery lymph node (HALN) (Level 8a of the Japanese Pancreas Society classification system8) could be an interesting prognostic marker due to its easy access, avoidance of major surgery and the possibility of identifying patients who would not benefit from PD but from palliative treatment instead. Several studies have evaluated the prognostic value of HALN metastases with conflicting results. Some reported that HALN involvement correlated with a significant decrease in survival,9–12 describing a prognosis similar to that of patients with liver metastases or peritoneal disease.13 Meanwhile, other authors indicated that there were no differences in survival between patients with HALN involvement compared to those with lymph node involvement at any other level.14

The objective of this study was to analyze the impact of metastatic involvement of the common HALN (Level 8a of the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery [ISGPS]) on the survival of patients operated on for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PA) of the head of the pancreas.

MethodsThis is an observational, retrospective, single-center study of patients who underwent PD for PA of the head of the pancreas with curative intent at our hospital between January 2005 and December 2014, with follow-up until November 2018. HALN and peripancreatic lymph nodes (PPLN) were identified and analyzed histologically separately.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration on ethical principles for medical research and approved by our hospital's Ethics Committee.

Staging StudyThe preoperative evaluation of patients involved a detailed medical history and physical examination, Ca 19.9 levels and thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT) scan for diagnosis and staging. In cases in which the diagnosis was done by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, the extension study was completed with a thoracic CT scan. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and endoscopic ultrasound with or without biopsy of the tumor were performed selectively in cases with uncertain diagnoses.

Patients were classified in accordance with criteria published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN 2012)15 into resectable, borderline resectable and unresectable tumors. Resectable tumors were defined as lesions of the head of the pancreas with no contact or less than 180° with no irregularity of the mesenteric-portal axis contour or arterial contact. The presence of lymphadenopathy in the region (hepatic hilum or peripancreatic) was not a criterion for unresectability.

Surgical Technique and Pathological StudyA pylorus-preserving PD was performed, as previously described,5 with duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy and Wirsung duct stent, hepaticojejunostomy with no stent, and antecolic gastrojejunostomy using a single loop. If there was suspected vascular invasion of the portal vein, the affected segment was removed and vascular reconstruction was subsequently performed. We carried out a standard lymphadenectomy8 of the head of the pancreas and periduodenal region with dissection of the hepatic pedicle, common hepatic artery, and excision of the retroportal pancreatic lamina and lymph tissue located to the right of the superior mesenteric artery without extended lymphadenectomy, described by other authors.16,17

Regarding the pathology study, the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC)18 pTNM classification was used, and the surgical resection margin analysis was based on the study by the Royal College of Pathologists.19,20 The HALN was identified during the dissection of the common hepatic artery and sent for histological analysis separately from the PPLN, extracted together with the excision of the surgical specimen.21

Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Follow-UpNo patient received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Initially and according to the protocol of the hospital, patients with risk factors for recurrence (metastatic lymph node involvement, perineural or microvascular invasion) were treated with adjuvant gemcitabine-based chemotherapy on an individual basis until 2008. However, patients of the present study were treated with gemcitabine-based adjuvant chemotherapy depending on the general condition, comorbidities and age of the patient. Initially, within a clinical trial22 they received radiotherapy associated with gemcitabine and 5-fluorouracil, and later gemcitabine without radiotherapy23 plus oxaliplatin or capecitabine according to the patient's clinical tolerance.

Follow-up studies included thoracoabdominal CT scan and Ca 19.9 every 4 months during the first two years, then every 6 months. Suspicion of recurrence by radiological imaging or elevation of tumor markers was confirmed by PET-scan.

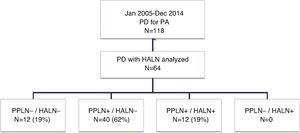

Study GroupsFor the purpose of this study, the patients were divided into four groups (Fig. 1) according to the presence of metastasis in the HALN or PPLN. These four groups were: patients without lymph node involvement (PPLN−/HALN−), patients with peripancreatic lymph node involvement and negative HALN (PPLN+/HALN−), patients with hepatic artery and peripancreatic lymph node involvement (PPLN+/HALN+), and patients without peripancreatic involvement but positive HALN (PPLN−/HALN+). Data was collected for different variables, including patient characteristics, pathological characteristics of the tumor, postoperative morbidity according to the Clavien-Dindo classification criteria,24 postoperative mortality and survival.

SurvivalOverall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of the last follow-up visit or death, and disease-free survival (DFS), from the date of surgery to the date of the first recurrence excluding postoperative mortality, which was defined as that which occurred during admission or during the first 30 days after surgery.

Statistical AnalysisA descriptive analysis was performed; the categorical variables are presented in total number and percentage, and the quantitative variables in medians and range. For the comparison of groups (PPLN−/HALN− vs. PPLN+/HALN− vs. PPLN−/HALN+), the Kruskal Wallis test was used in the case of continuous variables and the chi-squared test with Fisher's correction for qualitative variables. For the analysis of OS and the cumulative probability of recurrence (inverse logarithm of DFS), the Kaplan–Meier curves and the log-rank test were used as well as the Cox regression analysis to study the risk factors for OS and DFS. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® Statistics Version 22.

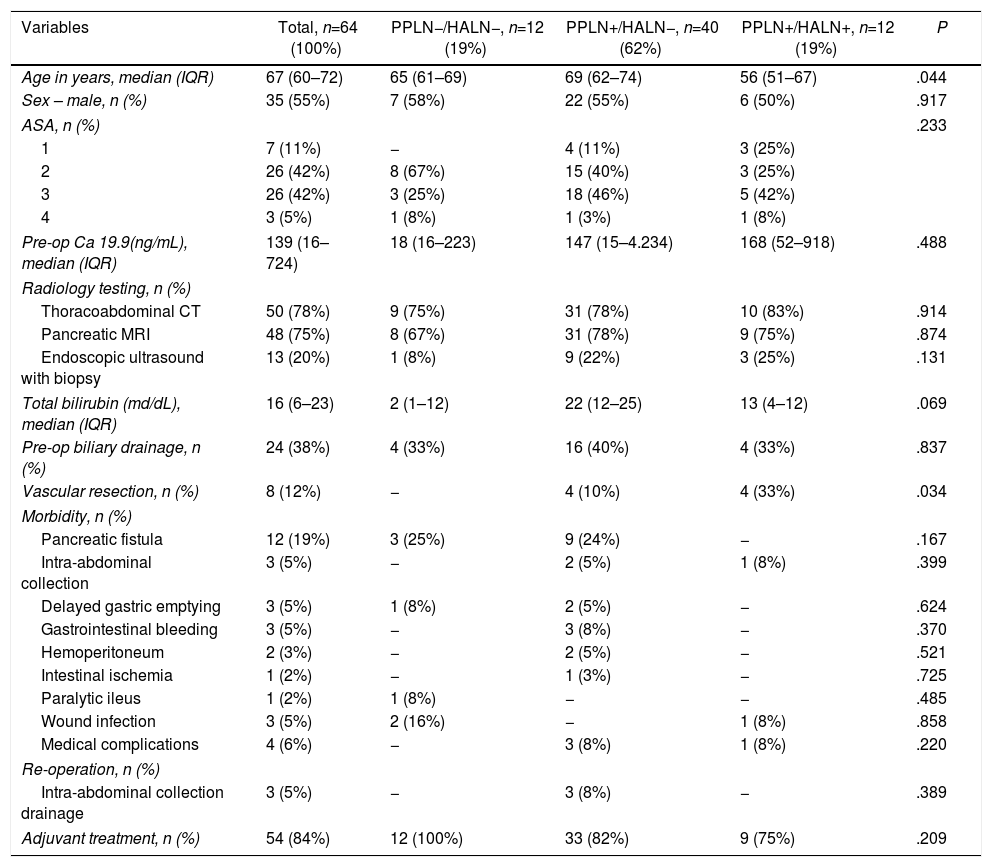

ResultsPatient Characteristics and Postoperative Follow-UpDuring the study period, 118 patients underwent PD for PA at our hospital, 64 of which were included in the study in which the common HALN and the PPLN were identified intraoperatively and sent for histological analysis separately. The characteristics of the patients are reflected in Table 1. The median follow-up of the present series was 20 months (r: 1–159 months).

Patient Characteristics.

| Variables | Total, n=64 (100%) | PPLN−/HALN−, n=12 (19%) | PPLN+/HALN−, n=40 (62%) | PPLN+/HALN+, n=12 (19%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 67 (60–72) | 65 (61–69) | 69 (62–74) | 56 (51–67) | .044 |

| Sex – male, n (%) | 35 (55%) | 7 (58%) | 22 (55%) | 6 (50%) | .917 |

| ASA, n (%) | .233 | ||||

| 1 | 7 (11%) | − | 4 (11%) | 3 (25%) | |

| 2 | 26 (42%) | 8 (67%) | 15 (40%) | 3 (25%) | |

| 3 | 26 (42%) | 3 (25%) | 18 (46%) | 5 (42%) | |

| 4 | 3 (5%) | 1 (8%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (8%) | |

| Pre-op Ca 19.9(ng/mL), median (IQR) | 139 (16–724) | 18 (16–223) | 147 (15–4.234) | 168 (52–918) | .488 |

| Radiology testing, n (%) | |||||

| Thoracoabdominal CT | 50 (78%) | 9 (75%) | 31 (78%) | 10 (83%) | .914 |

| Pancreatic MRI | 48 (75%) | 8 (67%) | 31 (78%) | 9 (75%) | .874 |

| Endoscopic ultrasound with biopsy | 13 (20%) | 1 (8%) | 9 (22%) | 3 (25%) | .131 |

| Total bilirubin (md/dL), median (IQR) | 16 (6–23) | 2 (1–12) | 22 (12–25) | 13 (4–12) | .069 |

| Pre-op biliary drainage, n (%) | 24 (38%) | 4 (33%) | 16 (40%) | 4 (33%) | .837 |

| Vascular resection, n (%) | 8 (12%) | − | 4 (10%) | 4 (33%) | .034 |

| Morbidity, n (%) | |||||

| Pancreatic fistula | 12 (19%) | 3 (25%) | 9 (24%) | − | .167 |

| Intra-abdominal collection | 3 (5%) | − | 2 (5%) | 1 (8%) | .399 |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 3 (5%) | 1 (8%) | 2 (5%) | − | .624 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 3 (5%) | − | 3 (8%) | − | .370 |

| Hemoperitoneum | 2 (3%) | − | 2 (5%) | − | .521 |

| Intestinal ischemia | 1 (2%) | − | 1 (3%) | − | .725 |

| Paralytic ileus | 1 (2%) | 1 (8%) | − | − | .485 |

| Wound infection | 3 (5%) | 2 (16%) | − | 1 (8%) | .858 |

| Medical complications | 4 (6%) | − | 3 (8%) | 1 (8%) | .220 |

| Re-operation, n (%) | |||||

| Intra-abdominal collection drainage | 3 (5%) | − | 3 (8%) | − | .389 |

| Adjuvant treatment, n (%) | 54 (84%) | 12 (100%) | 33 (82%) | 9 (75%) | .209 |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiology; HALN: hepatic artery lymph nodes; PPLN: peripancreatic lymph nodes; IQR: interquartile range

Regarding the study groups, both PPLN and HALN were negative in 12 patients (PPLN−/HALN−, 19%), PPLN were positive with negative HALN in 40 patients (PPLN+/HALN−, 62%) and both PPLN and HALN were positive in 12 patients (PPLN+/HALN+, 19%). No patient in our series had negative PPLN with positive HALN (PPLN−/HALN+, 0%). The mean number of resected lymph nodes in the entire series was 13 lymph nodes (r: 5–24). However, in two patients in the PPLN+/HALN− group and in the PPLN+/HALN+ group, the total number of resected lymph nodes was 5, with two and three involved lymph nodes, respectively, including the HALN in the last group, without affecting the final tumor staging.

Postoperative morbidity was recorded in 32 patients (50%). Table 1 analyzes each of the postoperative complications by groups. The overall postoperative mortality was 3% (n=2), both in the PPLN+/HALN− group, due to intestinal ischemia and pulmonary thromboembolism, respectively. So, according to the Clavien-Dindo classification, 53% were grade I complications, 16% grade II, 16% grade IIIa, 9% grade IIIb with the need for reoperation to drain intra-abdominal collections secondary to pancreatic fistula, and 6% grade V, corresponding to the two cases previously described.

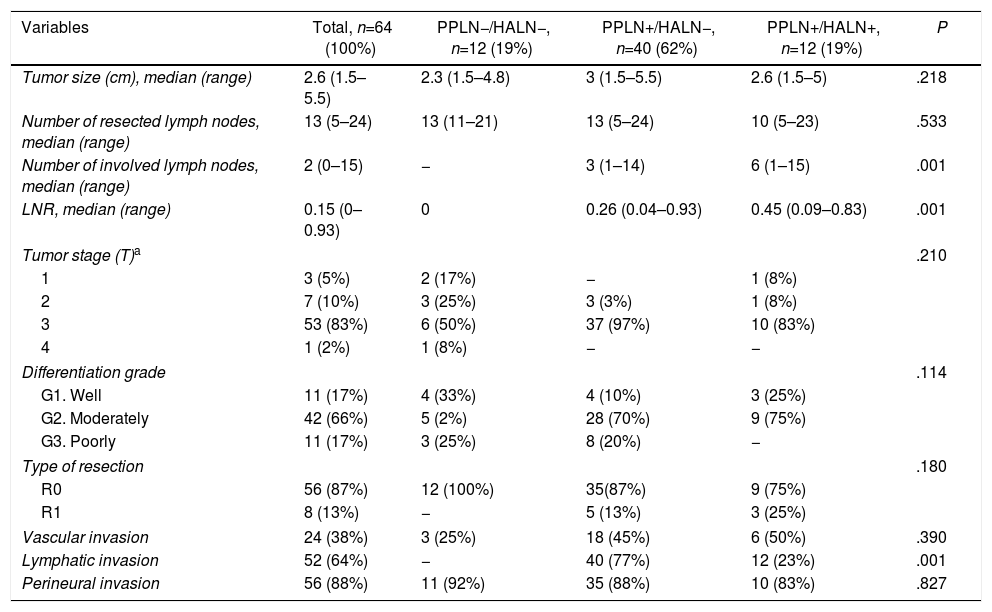

Table 2 describes the histopathological characteristics of the tumors.

Histological Tumor Characteristics.

| Variables | Total, n=64 (100%) | PPLN−/HALN−, n=12 (19%) | PPLN+/HALN−, n=40 (62%) | PPLN+/HALN+, n=12 (19%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size (cm), median (range) | 2.6 (1.5–5.5) | 2.3 (1.5–4.8) | 3 (1.5–5.5) | 2.6 (1.5–5) | .218 |

| Number of resected lymph nodes, median (range) | 13 (5–24) | 13 (11–21) | 13 (5–24) | 10 (5–23) | .533 |

| Number of involved lymph nodes, median (range) | 2 (0–15) | − | 3 (1–14) | 6 (1–15) | .001 |

| LNR, median (range) | 0.15 (0–0.93) | 0 | 0.26 (0.04–0.93) | 0.45 (0.09–0.83) | .001 |

| Tumor stage (T)a | .210 | ||||

| 1 | 3 (5%) | 2 (17%) | − | 1 (8%) | |

| 2 | 7 (10%) | 3 (25%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (8%) | |

| 3 | 53 (83%) | 6 (50%) | 37 (97%) | 10 (83%) | |

| 4 | 1 (2%) | 1 (8%) | − | − | |

| Differentiation grade | .114 | ||||

| G1. Well | 11 (17%) | 4 (33%) | 4 (10%) | 3 (25%) | |

| G2. Moderately | 42 (66%) | 5 (2%) | 28 (70%) | 9 (75%) | |

| G3. Poorly | 11 (17%) | 3 (25%) | 8 (20%) | − | |

| Type of resection | .180 | ||||

| R0 | 56 (87%) | 12 (100%) | 35(87%) | 9 (75%) | |

| R1 | 8 (13%) | − | 5 (13%) | 3 (25%) | |

| Vascular invasion | 24 (38%) | 3 (25%) | 18 (45%) | 6 (50%) | .390 |

| Lymphatic invasion | 52 (64%) | − | 40 (77%) | 12 (23%) | .001 |

| Perineural invasion | 56 (88%) | 11 (92%) | 35 (88%) | 10 (83%) | .827 |

HALN: hepatic artery lymph nodes; PPLN: peripancreatic lymph nodes; LNR: lymph node ratio.

In this study, 84% of patients received gemcitabine-based adjuvant chemotherapy, 75% had recurrence of the disease during the follow-up period, and 36% presented local and systemic recurrence after a disease-free time of 11 months (r: 1–49). In 35%, systemic recurrence was only observed after a disease-free time of 9 months (r: 1–66) and in 4% only local recurrence was observed after a disease-free time of 5 months (r: 2–24 months).

Survival AnalysisThe median OS of the total series was 20 months (r: 1–159 months), with a DFS of 12 months (r: 1–159 months) and no observed loss to follow-up during the period of study.

The median OS between the groups was: PPLN−/HALN− 64 months (r: 16–130 months); PPLN+/HALN− 18 months (r: 1–159 months); and PPLN+/HALN+ 13 months (r: 6–78 months). The median DFS between the groups was: PPLN−/HALN− 34 months (r: 2–130 months); PPLN+/HALN− 8 months (r: 1–159 months); and PPLN+/HALN 12 months (r: 1–66 months). Although there were significant differences in both OS (P=.007) and DFS (P=.030) between those patients without lymph node involvement vs. the groups with lymph node involvement, the median OS of patients with PPLN+ did not show significant differences depending on HALN involvement (P=.195) or median DFS (P=.617).

The 1, 3 and 5-year OS rates were statistically better in the PPLN−/HALN− group (82, 72 and 54%) than in the PPLN+/HALN− (68, 29 and 21%) and HALN+ groups (72, 9 and 9%) (Fig. 1). The cumulative probability of disease recurrence after 1, 3, and 5 years was statistically lower in the PPLN−/HALN− group (18, 46, and 55%) compared to the PPLN+/HALN− group (57, 80, and 89%) and PPLN+/HALN+ group (46, 91 and 100%) (Fig. 2).

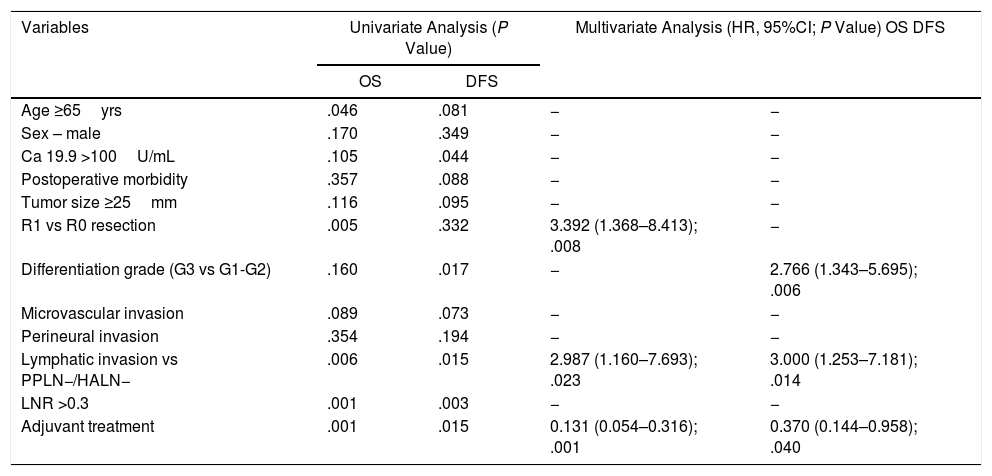

Analysis of OS and DFS Risk FactorsThe risk factors studied for OS and DFS were the following: age; sex; Ca 19.9 levels; overall morbidity; tumor diameter and differentiation; staging (T/N); R0/R1; lymph node ratio (LNR); microvascular, lymphatic and perineural invasion; and adjuvant treatment.

In our series, the main risk factors for OS in both the univariate and multivariate analyses were lymphatic invasion (HR: 2.987; 95%CI: 1.160–7.693) and R1 vs R0 resection (HR: 3.39; 95%CI: 1.368–8.413), while adjuvant treatment was a protective factor (HR: 0.13; 95%CI: 0.054–0.316) (Table 3).

Analysis of Risk Factors for Overall Survival (OS) and Disease-Free Survival (DFS).

| Variables | Univariate Analysis (P Value) | Multivariate Analysis (HR, 95%CI; P Value) OS DFS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS | DFS | |||

| Age ≥65yrs | .046 | .081 | − | − |

| Sex – male | .170 | .349 | − | − |

| Ca 19.9 >100U/mL | .105 | .044 | − | − |

| Postoperative morbidity | .357 | .088 | − | − |

| Tumor size ≥25mm | .116 | .095 | − | − |

| R1 vs R0 resection | .005 | .332 | 3.392 (1.368–8.413); .008 | − |

| Differentiation grade (G3 vs G1-G2) | .160 | .017 | − | 2.766 (1.343–5.695); .006 |

| Microvascular invasion | .089 | .073 | − | − |

| Perineural invasion | .354 | .194 | − | − |

| Lymphatic invasion vs PPLN−/HALN− | .006 | .015 | 2.987 (1.160–7.693); .023 | 3.000 (1.253–7.181); .014 |

| LNR >0.3 | .001 | .003 | − | − |

| Adjuvant treatment | .001 | .015 | 0.131 (0.054–0.316); .001 | 0.370 (0.144–0.958); .040 |

HALN: hepatic artery lymph nodes; PPLN: peripancreatic lymph nodes; HR: hazard ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; LNR: lymph node ratio.

Regarding the analysis of DFS risk factors, lymphatic involvement (HR: 2.8; 95%CI: 1.171–6.719) and the degree of differentiation (G3 vs. G1–G2) (HR: 2.76; 95%CI: 1.343–5.695) were statistically significant in both the univariate and multivariate analyses, while adjuvant treatment was a protective factor (HR: 0.3; 95%CI: 0.138–0.914) (Table 3).

DiscussionIt has been demonstrated that the presence of lymph node metastasis is an independent prognostic factor in patients treated surgically for PA7; furthermore, their location also significantly correlates with prognosis. Due to its easy access and dissection as well as its being anatomically constant, the HALN could play the role of sentinel node in PA. Some articles10–12,14 refer to the fact that this would help identify patients with poor long-term prognosis after surgery with curative intent. However, the results in the literature are contradictory.

The Connor et al. study12 evaluated the significance of LN8 and LN16 involvement in the survival of patients treated surgically for periampullary tumors. They studied 54 patients, for whom LN8 was independently analyzed, and they found a significant decrease in the median survival in patients with metastasis at this level; LN8 involvement was shown to be an independent prognostic factor in the multivariate analysis. The Maithel et al. study,14 however, analyzed the radiological correlation between lymphadenopathies of the hepatic artery and the bile duct in terms of resectability and survival in patients with resected periampullary tumors. The subgroup analysis of 49 patients, in whom the HALN had been recovered and analyzed individually, demonstrated that the patients who presented metastatic involvement at this level had a significant decrease in survival, similar to those with carcinomatosis or liver metastases. These studies included patients with different histological types, making it difficult to reach a firm conclusion and correctly analyze survival.

Subsequently, Cordera et al.11 evaluated 55 patients who underwent PD for PA, and worse OS was observed in the 10 patients with metastatic involvement of the HALN. Similar results were published by LaFemina et al.10 in a study that included only patients who underwent PD for PA. They found that 23 out of a total of 147 patients had HALN involvement, with statistically significant worse OS and DFS.

However, in line with our work, Philips et al.25 analyzed the prognostic relevance of HALN in a total of 247 patients who underwent PD for PA, 41 of whom presented metastasis in that area. These authors found a worse OS in patients with HALN involvement, but with no significant differences compared to patients with lymphatic involvement of both the HALN and PPLN. In our study, 19% presented HALN and PPLN involvement, and 62% presented PPLN involvement without HALN involvement. We were able to verify that OS was similar in both groups and was statistically lower than in patients without lymph node involvement. In terms of the cumulative probability of recurrence, there were also no differences between the PPLN+/HALN+ group and the PPLN+/HALN− group, but their rates were statistically higher than in patients with no lymph node involvement. This demonstrates that, more than HALN involvement, what ultimately determines survival in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma is lymph node involvement.

On the other hand, we did not identify cases of isolated HALN involvement in our series, which is consistent with other similar studies where its presence has been extremely rare (1.2%–2%). This suggests that HALN is not a first step in lymphatic spread, and that its involvement could be related to a greater tumor burden and biologically more aggressive tumors, as has been pointed out in other publications.9,10,25

Finally, the multivariate analysis of the risk factors for both OS and DFS in our series showed that lymph node involvement turned out to be the main factor for a poor prognosis. Although affected resection margins had an impact on OS, they did not on DFS, which was mainly influenced by the degree of tumor differentiation. Neither preoperative tumor marker values – nor vascular involvement were significant compared to other series.3,26–28 Although Ca 19.9 values – were slightly higher in the group with lymph node involvement, there were no significant differences between groups, nor were we able to demonstrate their impact on survival. Panaro et al.29 have recently shown that microvascular invasion, margin involvement and lymph node involvement are the main risk factors in univariate analyses of both DFS and OS, and that microvascular invasion is the main determinant of long-term survival. On the other hand, other recent studies30,31 have reported that lymph node involvement is associated with early recurrence and worse long-term prognosis, regardless of margin involvement or vascular invasion. In short, this shows that the adenocarcinoma of the pancreas is a systemic disease that requires effective adjuvant chemotherapy for its control, which has been proven to be the main protective factor consistent with publications in the literature.32,33

Despite the limitations of our study, due to its retrospective nature, with a limited and different sample size in each group, the results of our initial experience suggest that HALN involvement is associated with PPLN involvement and, therefore, with a greater tumor burden and worse biological behavior. Taking into account that the HALN is positive in 10% to 24% of patients11,12,24 (19% in our series), its preoperative identification, either by laparoscopic staging or endoscopic ultrasound biopsy, could preoperatively identify a group of patients who are candidates for neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Nonetheless, we conclude that, although lymph node involvement impacts the long-term survival of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, we have not been able to identify HALN involvement as a prognostic marker per se, and it should not be considered, to date, a criterion for unresectability.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors thank Santiago Pérez-Hoyos, biostatistician of the Statistics and Bioinformatics Unit at the Institut de Recerca del Vall d’Hebron, for the review of the statistical analysis.

Please cite this article as: Rodrigues V, Dopazo C, Pando E, Blanco L, Caralt M, Gómez-Gavara C, et al. ¿Es realmente la afectación del ganglio de la arteria hepática un factor de mal pronóstico en el adenocarcinoma de páncreas? Cir Esp. 2020;98:204–211.