Male pelvic exenteration is a challenging procedure with high morbidity. In very selected cases, the robotic approach could make dissection easier and decrease morbidity due to the better vision provided and higher range of movements. In this paper, we describe port placement, instruments, minilaparotomy location, and the stepwise sequence of these procedures. We address 3 different situations: total pelvic exenteration with abdominoperineal resection, colostomy and urostomy; pelvic exenteration with colorectal/anal anastomosis and urostomy; and pelvic exenteration with abdominoperineal resection, colostomy and urinary tract reconstruction.

La exenteración pélvica masculina es un procedimiento complejo con elevada morbilidad. En casos muy seleccionados, el abordaje robótico puede facilitar la disección y reducir la morbilidad gracias a la mejor visión y versatilidad de movimientos. Describimos la técnica de exenteración pélvica robótica sistematizada con DaVinci Xi y sus variantes en varones, tras haber intervenido 3 casos en nuestro Centro. Describimos la colocación de trocares, material necesario, localización de minilaparotomía y secuencia de los procedimientos a realizar paso a paso. Distinguimos 3 supuestos: Exenteración pélvica total con amputación de recto, colostomía y urostomía; Exenteración pélvica con preservación de esfínter, anastomosis colo-rectal/anal y urostomía; Exenteración pélvica con amputación de recto, colostomía y reconstrucción de tracto urinario.

Male pelvic exenteration and its variants are indicated in patients with locally advanced bladder, prostate, or rectal tumors, local recurrences, or synchronous tumors of these organs. It is an aggressive surgery with high morbidity, but a minimally invasive approach can reduce bleeding and wound infection in selected cases.1,2 However, the laparoscopic approach is limited by the technical difficulties involved in dissection in a closed and narrow space, such as the male pelvis.2 The robotic approach, thanks to its better vision and versatility of movements, facilitates dissection and could reduce the conversion rate and morbidity, while maintaining oncological results similar to those obtained by laparotomy.3,4 The technique has been further developed in the female pelvis, and only a few cases of robotic pelvic exenteration have been published in males. We have not been able to find a description of the procedure as detailed as the one presented herein.

We describe the systematized robotic pelvic exenteration technique with the DaVinci Xi and its variants in males, including robotic trocar placement, necessary material, location of the minilaparotomy (ML) and sequence of procedures to be performed. All this is adapted to whether reconstruction of the tract is possible or not.

Surgical techniqueTotal pelvic exenteration with resection of the rectum, colostomy and urostomyComplete exenteration is the most common technique. In general, cases selected for the minimally invasive approach include locally advanced primary tumors with no posterior or lateral involvement, bladder or prostate recurrence with rectal involvement (2 of our cases), or highly selected cases of anterior rectal recurrence. In this situation, reconstruction is usually ruled out due to the lack of a sufficient margin, the high risk of local recurrence, and the frequent association of radiotherapy as the initial treatment of the primary tumor and/or recurrence.

Procedure description- 1

Preoperative preparation: prehabilitation according to the ERAS protocol, bowel preparation, prophylactic antibiotic therapy, and DVT prophylaxis. Marking of left colostomy and right urostomy sites by the stoma therapist.

- 2

Patient position: non-slip mattress, supine position, lithotomy position with leg straps, slight elevation of the pelvis so that the knees are on a lower plane and in order to avoid hitting the legs with the robotic arms; right lateral turn 20º–30º, Trendelenburg 30º–45º; sterile bladder catheterization.

- 3

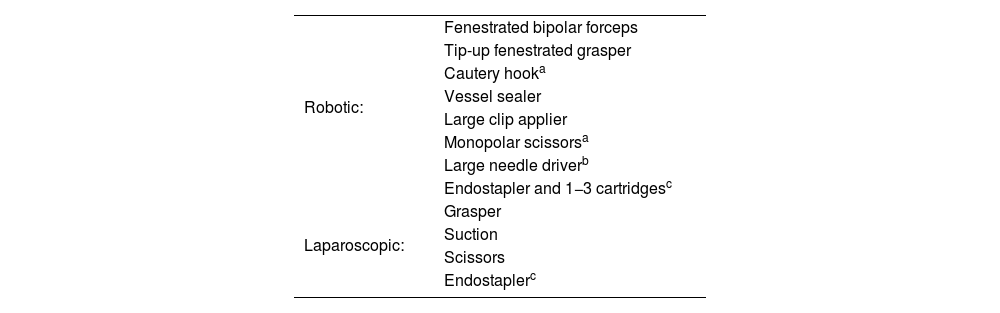

Robotic and laparoscopic material are described in Table 1.

- 4

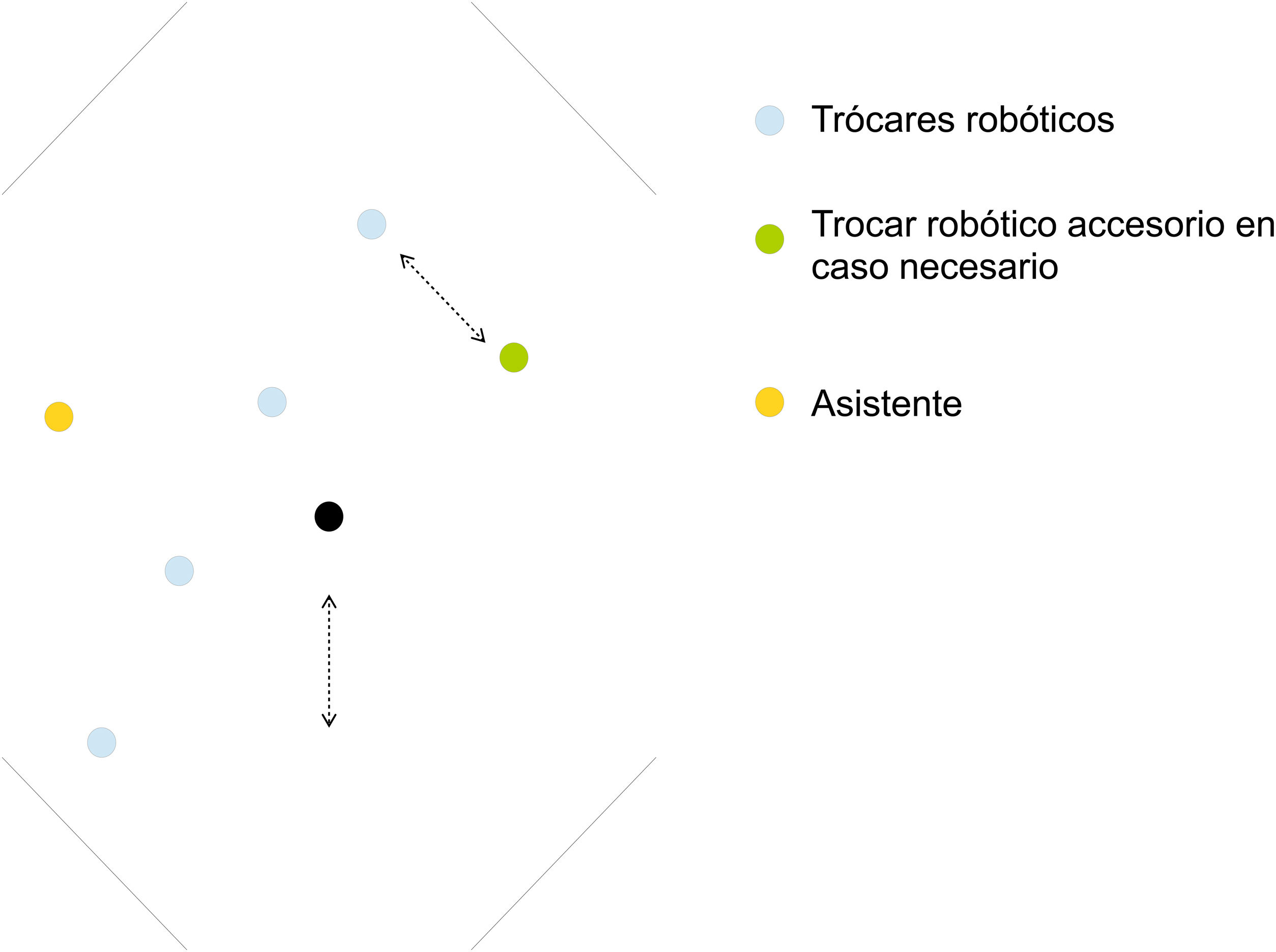

Trocar placement: access with a Veress needle; pneumoperitoneum with Airseal® device (facilitates viewing during pelvic dissection); 4 robotic trocars measuring 8 mm (the lower is 12 mm if the robotic endostapler is used) diagonally from the right anterosuperior iliac spine, 3−4 cm medial to the midline or the left mid-clavicular line, separated 6−10 cm (depending on patient size) (Fig. 1). Since in this case it will not be necessary to systematically mobilize the splenic flexure of the colon, we can place the trocars along a more horizontal line than described above. The 12-mm accessory trocar (if the robot endostapler is used, this can be 8 mm) located between the right iliac spine and costal margin at least 6 cm from other trocars. The trocars are placed so that one of them coincides with the future urostomy orifice. If the trocar placed most superior and left does not reach the pelvis well, another 8 mm robotic trocar can be placed in the left hypochondrium (LHC).

- 5

Positioning (“docking”) and target determination: parameters are established in the robot column for entry from the left of the patient and “lower abdomen”. The target is set at the level of the left external iliac vessels. For the urological procedure phase, re-docking can be performed by selecting “pelvis” and setting the target centered on the pelvis (usually not necessary). Arms 1–4 of the upper trocar are attached to the lower. The most common placement of the instruments is: Arm 1 - “tip-up”; Arm 2 - bipolar fenestrated; Arm 3 – camera; Arm 4 – dissection, cutting and suturing instruments. However, this arrangement may vary throughout the procedure depending on technical needs and the preferences of the surgeon.

- 6

Minilaparotomy and specimen extraction: extraction of the specimen will be carried out through a perineal wound, and the ML will be periumbilical for urological reconstruction using the Bricker technique.

- 7

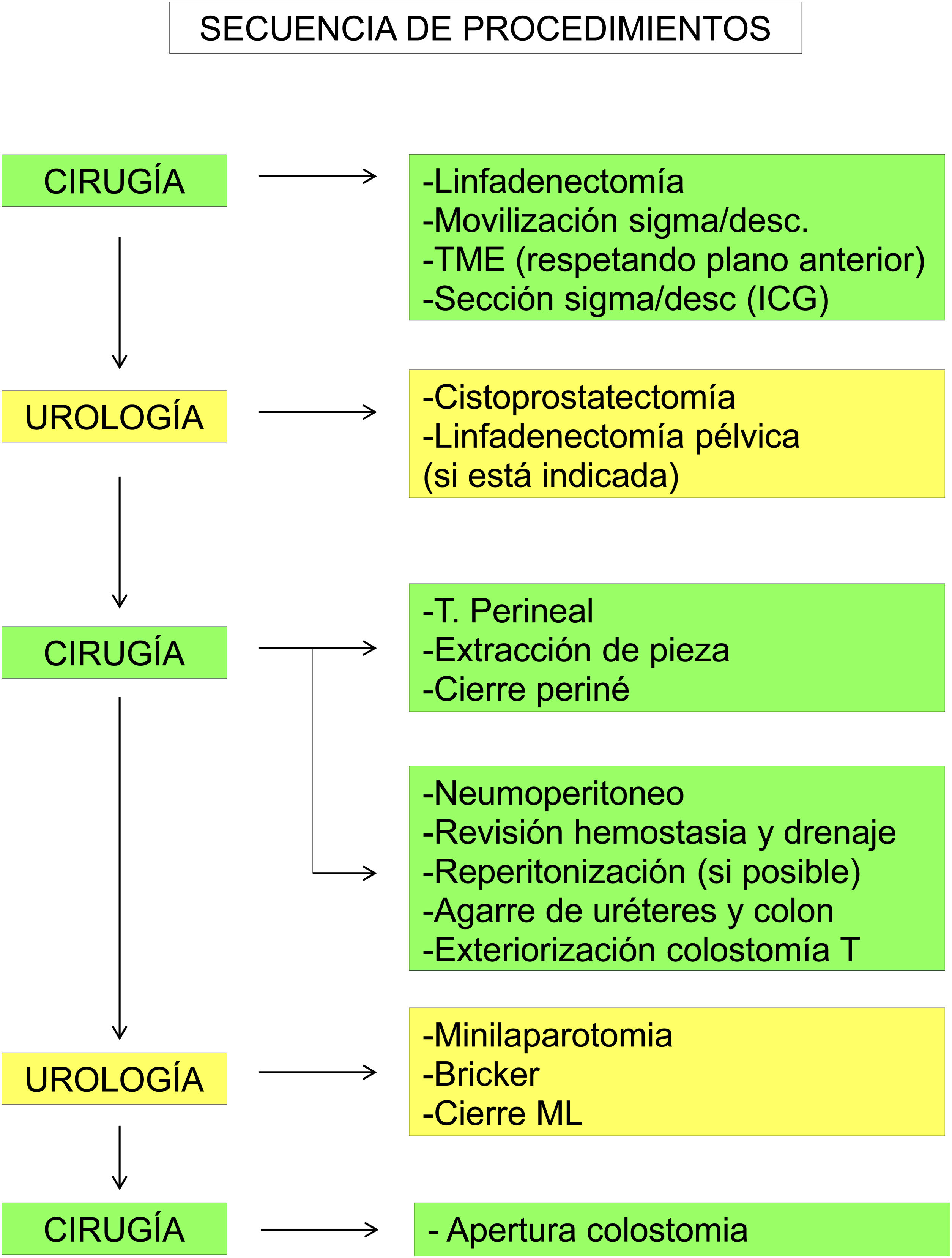

Sequence of procedures (Fig. 2):

- 7.8

The Gastrointestinal Surgery team starts with ligation (and lymphadenectomy, if necessary) of the inferior mesenteric artery and vein and mobilization of the sigmoid and descending colon from medial to lateral. Since an end colostomy will be performed, in most cases it will not be necessary to mobilize the splenic flexure.

- 7.9

We continue with the pelvic dissection of the rectum with complete excision of the mesorectum until reaching the levator plane, respecting the anterior plane so as not to disrupt areas with tumor involvement, followed by en bloc extraction of the specimen. Indocyanine green is used to confirm correct vascularization of the zone proximal to the division of the descending/sigmoid colon; division is performed with an endostapler inserted through an accessory trocar (less costly) or through the inferior robotic port.

- 7.10

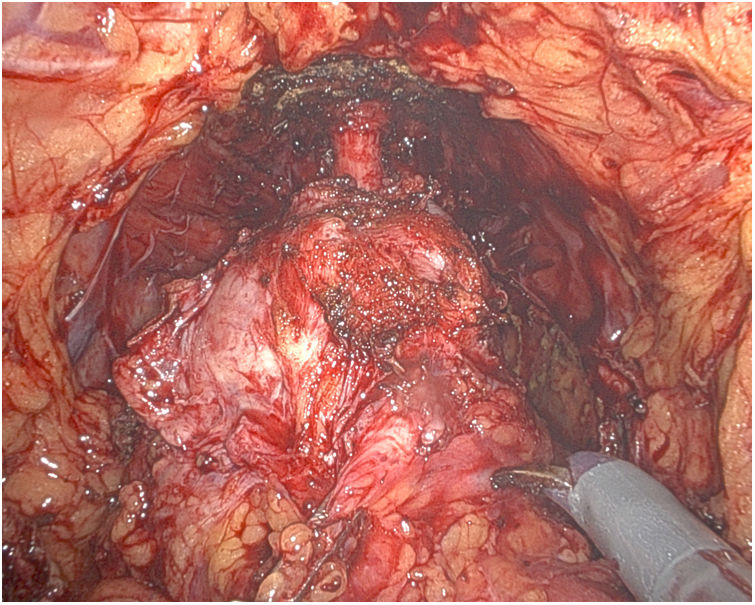

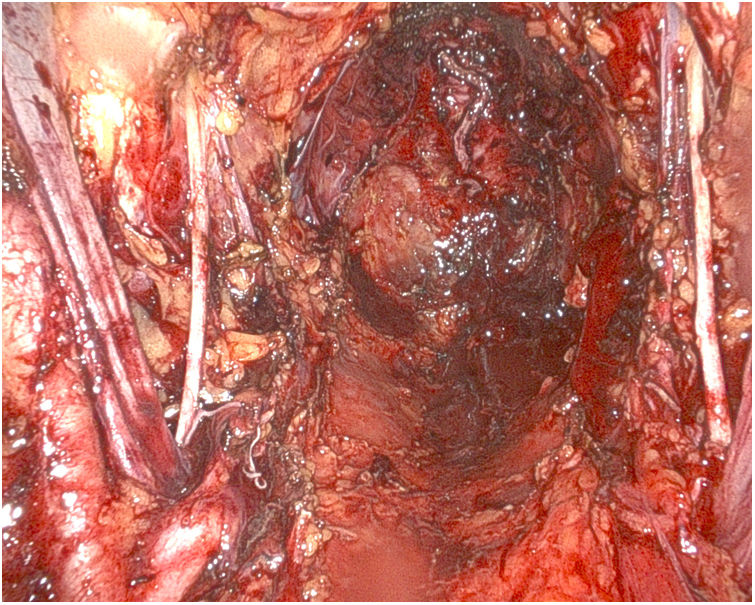

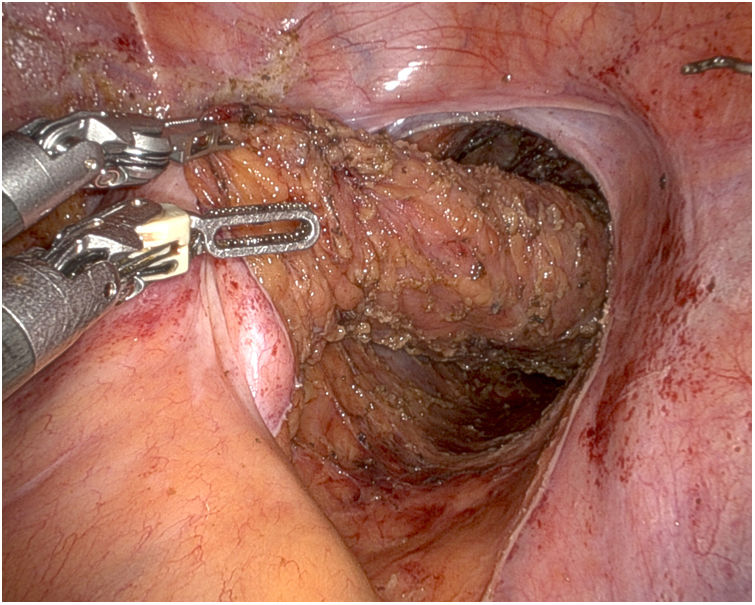

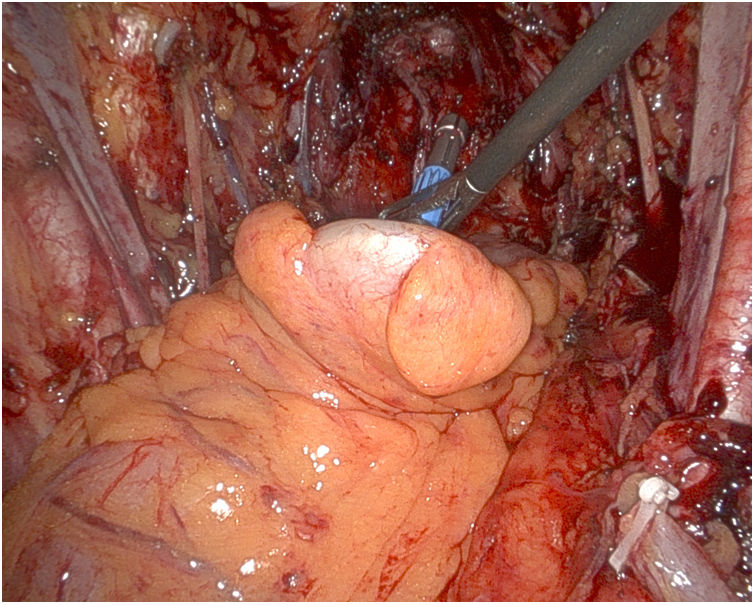

Afterwards, the Urology team performs a radical cystoprostatectomy, leaving the en bloc specimen with the rectum (Fig. 3), and pelvic lymphadenectomy (when indicated) (Fig. 4). As we mentioned before, re-docking and/or placement of a new trocar in the LHC may be necessary.

- 7.11

Perineal step to complete the resection, with en bloc extraction of the specimen through the perineum and closure of the perineal opening.

- 7.12

Pneumoperitoneum. The possibility and indication of reperitonizing the pelvis (very unlikely in rectal recurrence) is assessed, and, if necessary, re-docking and repeating with 3/0 barbed suture. Pelvic drainage. Both ureters and the colon are clamped with a laparoscopic clamp for later identification and exteriorization.

- 7.13

Exteriorization of the left terminal colostomy at the site marked by the stoma therapist. The colon is left closed.

- 7.14

Periumbilical minilaparotomy. Creation of urostomy according to the Bricker technique, exteriorized through one of the trocar holes that coincides with the mark of the stoma therapist.

- 7.15

Closure of ML and 12-mm accessory trocar aponeurosis. Opening made for colostomy.

This is indicated in rectal tumors associated with synchronous tumors or with invasion of the bladder and/or prostate, and viceversa, provided that the rectal involvement allows for preservation of the sphincter. In these cases, we rule out urinary tract reconstruction due to poor functional results related with exenteration and the high risk of complications when reconstruction of both tracts is associated.

The preparation and positioning of the patient, material, trocar placement and docking is similar to that described for total pelvic exenteration. Trocars will be placed on the previously described diagonal line. If the distal division of the rectum is to be performed with the robot, the lower trocar must be 12 mm.

After performing the anterior resection of the rectum (Fig. 5) with distal division and cystectomy and/or prostatectomy, an infraumbilical mid-line minilaparotomy is performed (Fig. 1), which is protected with a handport, through which the resection pieces are extracted and the colon is prepared for the anastomosis. The handport is covered, the colorectal anastomosis is created (Fig. 6), and both ureters are held with laparoscopy forceps. Next, and since the urostomy will be exteriorized in the RIF (which prevents us from performing an ileostomy), we will perform a right transverse lateral colostomy that is left closed. Finally, the Urology team will proceed through the same ML for the reconstruction with the exteriorized Bricker technique in the area marked by the stoma therapist, taking advantage of one of the trocar orifices. After closing the ML and the remaining orifices, the colostomy is opened, thus completing the procedure.

Indicated in rectal tumors that hinder sphincter preservation, associated with bladder and/or prostate tumors that allow for reconstruction. The procedure would be similar to the first case. After closing the perineum, the Urology team proceeds with tract reconstruction, with no ML in the case of prostatectomy, or with periumbilical ML and orthotopic neobladder in the case of cystectomy. Subsequently, the end colostomy is externalized.

We have performed the technique on 3 occasions. In 2 cases, total exenteration was performed with colostomy and urostomy due to recurrence of prostate cancer with rectal involvement, while another patient underwent cystectomy with urostomy, low anterior resection (LAR) and low colorectal anastomosis due to synchronous tumors of the bladder and rectum. One of the patients with total exenteration presented postoperative bleeding that required reoperation. The remainder presented no relevant complications.

DiscussionFirst of all, we would like to clarify that the purpose of this article is not to establish or discuss the indications for the robotic approach to male pelvic exenteration, but instead to establish a systemized approach for the technique. As in any surgical technique, the initial cases should be well selected to avoid those that may entail greater technical difficulties. Cases that would probably benefit most from the robotic approach include locally advanced primary tumors of the rectum, bladder, or prostate, or recurrences of bladder or prostate cancer with rectal invasion, without involvement of the posterior or lateral wall, as well as synchronous tumors.

Radical cystectomy and prostatectomy, as well as LAR and APR with a robotic approach, have been standardized techniques in our hospital since 2019. The experience gained has allowed us to approach selected cases that required pelvic exenteration through this route. Although in the first case we found difficulties in the distribution of trocars, laparotomy and sequence of procedures, we analyzed the possibilities and have found what we consider to be the best option, and which we have established as the systematic approach for this robotic procedure.

In the literature, there are very few data published on the robotic approach to male exenteration. The series by Williams et al. is the longest published with 7 cases.5 It describes the procedure but does not go into detail about trocar placement, material, or laparotomy location. Compared to open surgery, the results are better in terms of need for transfusion, hospital stay, reoperations, serious complications, and R0 resection; however, the low number of cases does not allow conclusions to be drawn. Other mixed series or isolated cases do not provide a detailed, systematic description of the technique.4,6 Systematization of the procedure establishes an appropriate sequence of surgical steps from beginning to end that can shorten surgical times, reduce the number of trocars, optimize the ML and facilitate the coordination of 2 teams and their actions, thereby avoiding unforeseen events that may hinder the development of an already complex procedure.

We are aware of the limitation that the low number of cases performed can have when establishing a systematic technique. However, we believe that it does allow us to propose systematization of the procedure for selected cases, which can serve as a foundation from where modifications can be introduced after greater experience. We must emphasize that we propose systematization of the robotic exenteration technique for when it is indicated, not standardization of the robotic technique for exenteration.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Alonso Casado O, Nuñez Mora C, Ortega Pérez G, López Rojo I. Abordaje robótico de la exenteración pélvica masculina. Sistematización de la técnica. Cir Esp. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2023.03.003