Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) is an effective treatment for patients with terminal chronic liver disease, despite the high incidence of biliary complications. The objective is to evaluate the results and long-term impact of biliary complications after THDV.

Patients and methodsFrom 2000 to 2010, 70 right lobe LDLT were performed. Biliary complications (leakage and stenosis) of the 70 LDLT recipients were collected prospectively and analysed retrospectively.

Results39 patients (55.7%) had some type of biliary complication. 29 presented a leak, and of these, 14 subsequently developed a stricture. In addition, 10 patients had a stenosis without prior leakage. The median time to onset of stenosis was almost a year. Patients with previous biliary leakage were more likely to develop stenosis (58% vs 29.5% at 5 years, P=.05). With a median follow-up of 80 months, 70.8% of patients were successfully treated by interventional radiology. After excluding early mortality, there were no differences in survival according to biliary complications. A decrease of biliary complications was observed in the last 35 patients compared with the first 35.

ConclusionsLDLT is associated with a high incidence of biliary complications. However, long-term outcome of patients is not affected. After a median follow-up time of nearly seven years, no differences were found in survival according to the presence of biliary complications.

El trasplante hepático de donante vivo (THDV) es un tratamiento eficiente para pacientes con hepatopatía crónica terminal, a pesar de la elevada incidencia de complicaciones biliares. El objetivo es evaluar los resultados y el impacto a largo plazo de las complicaciones biliares tras el THDV.

Pacientes y métodosDesde 2000 hasta 2010, se llevaron a cabo 70 THDV usando el hígado derecho como injerto. Se recogieron prospectivamente y analizaron retrospectivamente las complicaciones biliares (fugas y estenosis) de estos 70 receptores de THDV.

Resultados39 pacientes (55,7%) presentaron algún tipo de complicación biliar. 29 presentaron una fuga y, de ellos, 14 desarrollaron posteriormente una estenosis. Además, 10 pacientes más presentaron una estenosis sin una fuga previa. La mediana de tiempo hasta la aparición de una estenosis fue de casi un año. Los pacientes con una fuga biliar previa presentaron una mayor probabilidad de desarrollar una estenosis (58% vs 29,5% a 5 años, p = 0,05). Con una mediana de seguimiento de 80 meses, 70,8% de los pacientes fueron tratados satisfactoriamente mediante radiología intervencionista. Tras excluir la mortalidad inicial, no hubo diferencias de supervivencia en función de las complicaciones biliares. Se observó una disminución de las complicaciones biliares en los segundos 35 pacientes en comparación con los primeros.

ConclusionesEl THDV está asociado a una incidencia elevada de complicaciones biliares. Sin embargo, los resultados a largo plazo de los pacientes no se ven afectados. Tras un tiempo de seguimiento mediano de casi siete años, la supervivencia en función de la aparición de complicaciones biliares permaneció sin diferencias.

The introduction of living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) was determined by the need to increase the number of grafts in order to perform more transplants and reduce deaths on the waiting list. In the East, LDLT became the only option because of the virtual absence of cadaveric donation. However, in the West, LDLT has become another alternative within the organisation of donation programmes. To date, LDLT has had limited application primarily because of the risk to the donor which may end with significant morbidity and mortality.1–4 Furthermore, the results published in LDLT series are often controversial, as this type of transplant is associated with an increased morbidity and occasionally decreased survival.

One aspect that seems to compromise the long-term outcome of this type of transplantation is the high incidence of biliary complications.5,6 The characteristics of this type of complication seem different from those reported in liver transplants from cadaveric donors.7 Biliary anastomoses in LDLT are characterised by the frequent presence of more than one small bile duct, which complicates anastomosis due to its proximity to the portal vein and the hepatic artery. These aspects increase the complexity of the procedure and significantly increase the difficulty in treating complications.8–12 However, despite the high incidence of biliary complications; recently published series show no impact on results.13

Although the existence of these complications has been widely described in literature,5,8,14 the characteristics in terms of long-term prognosis and treatment have not yet been specifically described. Similarly, the influence on results in the long-term has not been clearly established.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of biliary complications on the overall results in the long-term, as well as in relation to the type of treatment performed.

Patients and MethodsThe liver transplant programme at the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona was begun in 1988. Since then, over 1600 liver transplants have been performed. Since the beginning of the LDLT programme, in the year 2000, 70 procedures have been performed. This study analyses biliary complications in the 70 LDLT cases in our institution, which up to the present has had an immediate retransplantation rate of 1.4% (one patient) and long-term retransplantation rate of 2.8% (2 patients). All biliary complications described in this study are associated with the use of a right liver graft from the donor.

This work is an observational study with prospectively collected data, in order to retrospectively analyse the overall incidence of biliary complications. A total of 70 patients underwent LDLT, representing 4.4% of the overall series of liver transplant patients.

Details of the Surgical ProcedureAll patients received the right liver graft of their donor (liver segments v to viii) without the middle hepatic vein, which remained in the donor (a detailed explanation of the procedure has been published previously).15,16 In the donor, following the identification of the bile duct and other structures in the hepatic hilum and the right hepatic vein, liver transection was performed using CUSA™ (Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator, Tyco Healthcare, Mansfield, MA, USA) associated with TissueLink ™ (TissueLink Medical Inc., Dover, NH, USA), maintaining the graft perfused until removal. The bile duct was sectioned at the end of the transection in order to be able to perfectly identify the anatomy and choose the best possible area for section. In the recipient, portacaval shunt was always performed as well as haemodynamic monitoring in order to avoid portal hyperperfusion following reperfusion (the objective was to maintain a portal flow under 2000mL/min) at the same time ensuring an effective decrease of the initial portal hypertension (hepatic venous pressure gradient below 15mmHg).

Biliary reconstruction was, whenever possible, a single duct-to-duct anastomosis. Only one bile duct was obtained in the graft in 33 cases (47.1%), 2 ducts in 32 cases (45.7%) and 3 ducts in 5 cases (7.1%). Of the 70 recipients, 53 patients were reconstructed using a duct-to-duct anastomosis, 20 of them using a ductoplasty to join the 2 ducts, and the remaining 17 were reconstructed using a hepaticojejunostomy, with only 3 ductoplasties in this group. All anastomoses were tutored with the use of a Kehr drainage. At the end of surgery, 2 Jackson-Pratt drains were placed.

The demographic characteristics of the recipients are shown in Table 1.

Demographic Data of LDLT Recipients.

| Age (years) mean±DE (range) | 54.4±10.5 (23–69) |

| Sex, M/F | 46/24 |

| MELD score (range) | 13.4±5.1 (2–26) |

| Child–Pugh (A/B/C) | 17/28/25 |

| Indication for transplant, % | |

| HCV Cirrhosis | 26 (37.1) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 24 (34.3) |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 10 (14.3) |

| Other | 10 (14.3) |

| Hospitalisation (days) mean±DE (range) | 41.2±26.3 (14–142) |

We considered two types of biliary complications: (a) patients with bile leakage and (b) patients with biliary stenosis.

Bile LeakageLeakages were diagnosed by the appearance of symptoms (abdominal pain, fever, bilious materials in the drain, etc.), and their severity determined initial treatment. Although each case was considered individually, once a bile leakage was diagnosed, our centre's treatment algorithm was followed. The most important aspects when treating a leakage are the general condition of the patient and the output. A compromised physical condition (high fever, signs of peritoneal irritation, hypotension, oliguria, etc.) or a high output would be per se indications of surgical treatment. On the other hand, a patient with a good general condition and low bile output would be a good candidate for conservative treatment (Fig. 1).

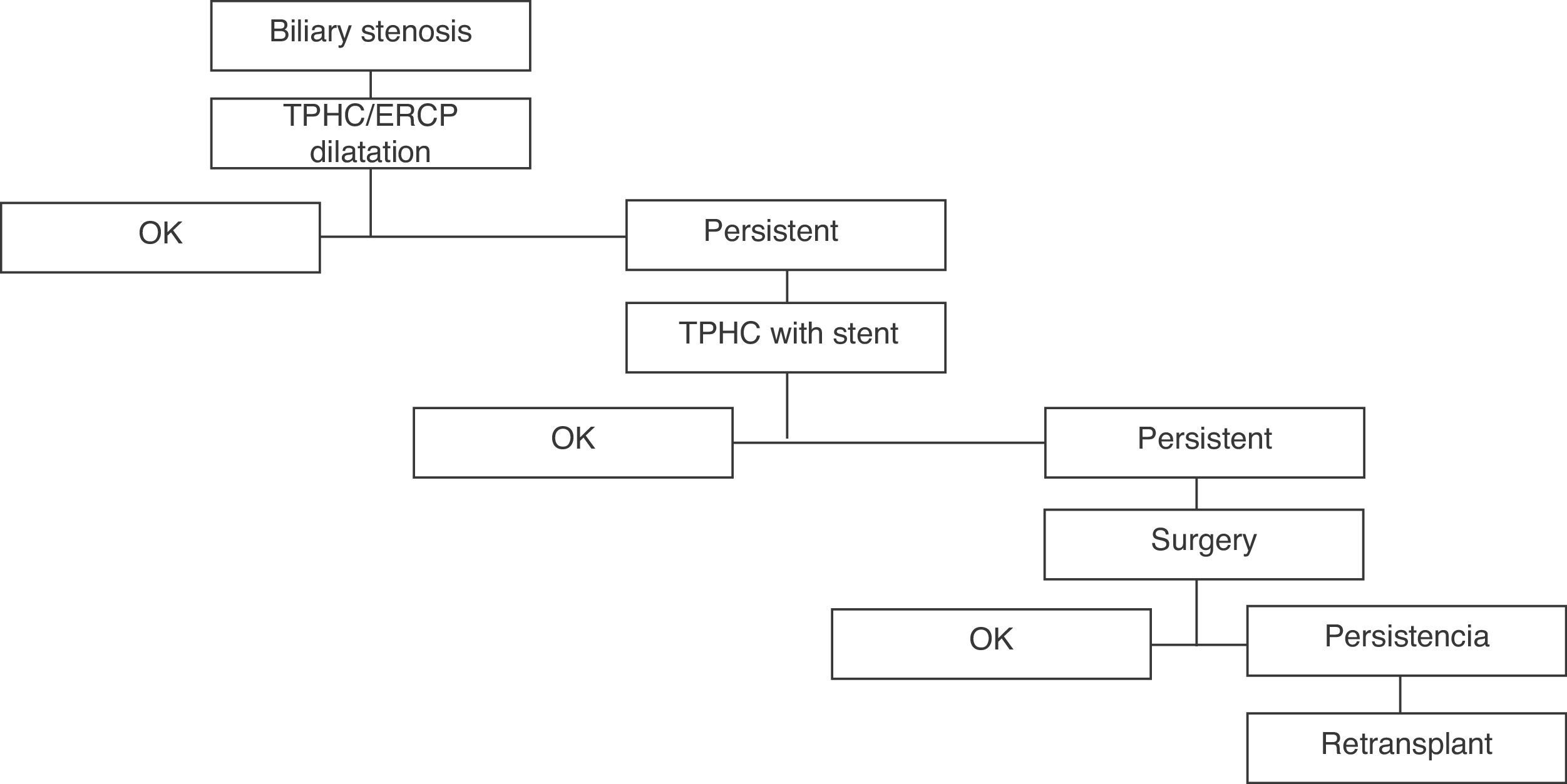

Biliary StenosisThe diagnosis of stenosis of the bile duct was also based on the presence of symptoms, although in the initial phase, it can only be recognised by abnormalities in laboratory analysis. It usually presented as a patient with cholestasis on analysis not attributable to any other cause, associated with a radiological decrease in the calibre of the biliary anastomosis. The treatment algorithm is shown in Fig. 2. We considered the time period from transplantation to the onset of symptoms. As a first treatment step, we tried to avoid surgical reoperation, using interventional radiology. In case of repeated failure of conservative treatment, surgery was performed. The procedure performed in the case of reoperation was always a hepaticojejunostomy. Liver retransplantation was considered in cases of treatment failure or parenchymal damage secondary to long-standing biliary obstruction (secondary biliary cirrhosis).

ResultsCharacteristics of Biliary ComplicationsPatients With Bile LeakageA total of 29 patients were diagnosed with bile leakage, accounting for 41.4% of the total. The source of the leakage was the anastomosis in 23 cases (79.3%), Kehr drain in 3 cases (10.3%) and the liver transection surface in 4 cases (13.8%). The median time from transplant to the detection of the leakage was 14 days (range 2–59 days). A third of the patients were operated on because of their clinical presentation, as shown in our protocol. The remaining patientsr were treated conservatively, with clinical monitoring or by aspiration of the collections until the symptoms cleared. Only one patient initially treated conservatively subsequently needed surgery. The presence of a bile leakage increased the hospital stay (48.59±27.1 days vs 35.3±24.7 days, P=.041). The patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Characteristics of Bile Leakages, Classified by Time of Occurrence (Early vs Late).

| Early leaks | Late leakages | |

| Number | 15 | 14 |

| Occurrence time, days±SD | 7.67±2.9 | 41.43±42.2 |

| Origin of leakage | ||

| Biliary anastomosis | 12 | 11 |

| Kehr drain | 1 | 2 |

| Liver surface | 3 | 1 |

| Initial treatment | ||

| Conservative | 2 | 3 |

| Percutaneous drainage | 7 | 8 |

| ERCP | 1 | 0 |

| Surgery | 5 | 3 |

| Final treatment | ||

| Percutaneous drainage | 5 | 5 |

| ERCP | 1 | 1 |

| TPHC | 3 | 3 |

| Biliary stent | 1 | 1 |

| Surgery | 5 | 4 |

Of the 24 patients who were diagnosed with stenosis of the bile duct during follow-up, 14 had previously presented an episode of leakage during the postoperative period (Table 3).

Characteristics of Biliary Stenosis Depending on the Occurrence or Not of a Biliary Leakage in the Initial Postoperative Period.

| Isolated Stenosis | Stenosis After Leakage | |

| Number | 10 (14.3%) | 14 (20%) |

| Time until diagnosis, days | 297±111 | 337±68 |

| Follow-up median | 60.5 months | 86.5 months |

| Final treatment | ||||

| Dilatation | 5 | 50% | 9 | 64.2% |

| +Stent | 2 | 10% | 1 | 7.2% |

| +Surgery | 3 | 30% | 1 | 7.2% |

| Retransplantation | 0 | 0% | 1 | 7.2% |

| Patients resolved | 10/10 | 100% | 12/14 | 85.7% |

With a median follow-up of 58 months (almost 5 years), 10 patients had stenosis. The time from transplantation to diagnosis was 297±111.6 days (range 60–1200 days). Table 3 specifies the procedure used for their treatment. Half of them were treated satisfactorily using only radiological dilatation. It is noteworthy that of the 5 patients who required biliary stent placement, 3 eventually underwent surgery. At the date of preparation of this manuscript, all isolated stenosis had been resolved.

Patients With Biliary Stenosis After an initial Episode of Bile LeakageWe identified 14 patients (20.3%) with an initial leakage after liver transplantation; such patients subsequently presented biliary stenosis. With a median follow-up time of 80.5 months, the mean onset time for stenosis symptoms was 337±68 days. This result, although similar, is slightly higher than in the group of patients with isolated stenosis. The stenosis disappeared in twelve patients (85.7%) through application of the treatment protocol. One patient with stenosis following an initial leakage developed secondary biliary cirrhosis 3 years after transplantation which resulted in liver function impairment and intractable pruritus, and was finally retransplanted with a graft from a cadaveric donor.

Overall Risk of Developing a Biliary StenosisThe overall probability of presenting a biliary stenosis after LDLT in our experience is 28% after one year and 40% after 3 years. If the patient develops a leakage episode in the early postoperative period, this probability increases to 58% after 3 years (Fig. 3).

Patients with biliary stenosis during follow-up required a higher number of hospitalisations. A mean of 7 readmissions were required to treat biliary complications. We could not find differences when comparing the characteristics of biliary stenosis in patients with or without previous biliary leakage.

Comparison of 2 PeriodsWhen we compared the first 35 patients (Group A, GA) with the last 35 (Group B, GB), we found a decrease in bile leaks in the second group (54.3% vs 28.6%, P=.048), which could be due to acquired experience. Furthermore, although there was a trend towards fewer stenosis in the second period (40% vs 28.6%), the difference is not significant, suggesting that experience may not influence the overall incidence of biliary stenosis. The results are shown in Fig. 4.

Impact of Biliary Complications on SurvivalOverall survival of patients and grafts after 1, 3 and 5 years was 91.3%, 78.0% and 75.9%, and 88.4%, 73.6% and 71.5%, respectively).

Given that the biliary complication that has a higher effect on survival is stenosis, we compared the mean patient and graft survival in relation to the presence or absence of biliary stenosis. With a mean follow-up of almost 7 years and after excluding early mortality (3 months after transplantation), there were no differences in patient and graft survival after 1 year, 3 years and 5 years, with or without complications, (100%, 91.3%, 91.3% vs 97.5%, 79.2%, 75.1% [P=.1] and 100%, 87.0%, 87.0% vs 92.4%, 74.5%, 70.4% [P=.1], respectively) (Figs. 5 and 6). In conclusion, biliary complications, especially stenosis, do not affect survival after LDLT.

The incidence of biliary complications after LDLT is considered high, and over time it has been associated with poorer patient results.17,18 This study confirms the high incidence of these complications. In total, 39 patients (55.7%) presented some type of biliary complication. However, when assessing the long-term results, we have been able to demonstrate that the existence of a leakage or biliary stenosis does not adversely affect the survival of patients or grafts.

Biliary complications should be divided into two groups: those associated with bile leakage and those in which a stenosis occurs. From a pathophysiological point of view, they are totally different. Bile leakage is a complication that occurs early and it may appear clinically in the context of a patient with good general condition, or in patients with deterioration in their clinical condition. In any case, the leakage must be resolved immediately, and once resolved, it should not affect the long-term results. In our experience, 20 patients (69%) were treated by endoscopy or interventional radiology. Nine patients required reoperation to repair the problem (31%). The learning curve is important with regard to the incidence of this complication. When we compare the first cases of the series with the last, in the second period the number of bile leakages decreased (19 vs 10, P=.048) as well as the number of operations required for treatment.

The occurrence of a stenosis is an unexpected finding in the majority of patients. Patients who develop it do so after a long asymptomatic period. We observed that the period from transplantation to the clinically evident stenosis is almost a year. From our point of view, we believe that this is very important, and the median follow-up time should always be included so that the true incidence of biliary complications can be known. All patients considered must be followed up for at least one year, and this is also the case for those patients who have developed biliary stenosis, either alone or after an initial leakage. With a median follow-up of 80 months, the risk of developing a biliary stenosis is 24.9% after one year and 38.3% after 3 years. If the patient develops a bile leakage, the probability increases to 28.6% and 58.1%, respectively. In the last 35 cases, there was a reduction in the number of stenosis (40%–28.6%). This is important because, by reducing leaks, we might decrease the overall number of stenosis. In fact, the trend towards decreased biliary stenosis after the first 35 cases could be the result of a decrease in leakages. However, this trend does not obtain statistical significance, suggesting that the learning curve may not affect this type of complication. This has already been suggested by other groups.19–21

With respect to treatment, two thirds of our patients were eventually treated with dilatation. The rest were either temporarily treated by stenting or underwent surgery. One aspect that seems clear and has been demonstrated previously by other groups22,23 is that biliary stenting should not be considered as a final treatment, since most of these patients eventually undergo surgery. Again, after a median follow-up period of 80 months (almost 7 years), only one patient in our series required a liver retransplantation due to a bile duct complication.

Only 3 of the 70 patients underwent retransplantation (one patient due to secondary biliary cirrhosis and another due to ischaemic cholangiopathy and one immediate retransplantation due to hepatic artery dissection). Overall survival of the graft one and 5 years after transplantation is 88.4% and 71.5%, respectively. These data have even improved in the last 35 cases with respective survival rates of 91.1 and 72.7%. The presence of biliary complications does not affect the probability of survival after one and five years. Although we excluded patients who died during the first 3 months after transplantation, we found that there is a trend towards better survival in patients who had some type of biliary complication. This could be explained by the low number of patients in each group. Results of other groups, such as the Pittsburgh series, have shown that despite the existence of a high rate of biliary complications, long-term survival is not affected.13

However, although survival may not be modified by biliary complications, the high number of admissions of these patients (mean readmissions due to stenosis of the bile duct is 6.92±4.3, representing an average stay of 73.6 days) probably has an impact on the quality of life of the patient, due to the presence of symptoms that require hospitalisation and in-patient treatment.

ConclusionThere is a high incidence of biliary complications in LDLT. Bile leakage may be related to surgical technique and can probably be reduced by acquiring experience. Only by reducing the number of bile fistula can we reduce the onset of stenosis in the long-term. However, the occurrence of a bile duct stenosis does not seem to be related to surgical experience. After a median follow-up of 80 months, we have been able to show that the occurrence of biliary complications does not appear to adversely affect the long-term results.

Conflict of InterestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please, cite this article as: Sánchez Cabús S, et al. Las complicaciones biliares en el trasplante hepático de donante vivo no afectan los resultados a largo plazo. Cir Esp. 2013;91:17–24.