It is accepted by the surgical community that laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the technique of choice in the treatment of symptomatic cholelithiasis. However, more controversial is the standardization of system implementation in ambulatory surgery because of its different connotations. This article aims to update the factors that influence the performance of LC in day surgery, analyzing the 25 years since its implementation, focusing on the quality and acceptance by the patient. Individualization is essential: patient selection criteria and the implementation by experienced teams in LC, are factors that ensure high guarantee of success.

Es bien aceptado por la comunidad quirúrgica que la colecistectomía laparoscópica (CL) es la técnica de elección en el tratamiento de la colelitiasis sintomática. Sin embargo, más controvertida es la estandarización de su realización en régimen de cirugía mayor ambulatoria (CMA) por las diversas connotaciones que presenta. Este artículo tiene por objeto actualizar los factores influyentes en la realización de la CL en régimen de cirugía sin ingreso, analizando estos 25 años desde su implantación, incidiendo en la calidad y aceptación del proceso por parte del paciente. Es fundamental la individualización del proceso: un estricto criterio de selección de pacientes y la realización por equipos con experiencia en CL, son factores que aseguran una alta garantía de éxito.

The postoperative period after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) follows a very short course, allowing patients to rapidly reinitiate oral intake and begin walking.1 Likewise, the intraoperative time of this technique has been progressively reduced. Due to these characteristics, most LC for uncomplicated cholelithiasis is currently conducted with short hospitalizations of 12–24h.

This situation led some authors in the early 90s to consider the possibility of performing LC as ambulatory surgery (ALC) with the highest possible level of safety. This would improve healthcare quality due to the reduced rate of nosocomial infection, cause minimal changes to patients’ habits and lifestyle, and optimize hospital resources by reducing the number of beds needed, increasing the volume of procedures and thereby reducing surgical waiting lists.2 It has been suggested that implementing ALC in our country would entail a savings of some 70 million euros (reduction in hospital stay costs), even before considering the costs eliminated from healthcare provided during hospitalization.3

But the main reticence about this ambulatory procedure is that many surgeons prefer time periods of at least 24h with an overnight hospital stay in order to quickly detect the appearance of any vital complications during the immediate postoperative period. A series of basic principles are therefore necessary to determine the use of ALC and ensure the highest probability of success with the utmost safety for patients:

- (a)

selection criteria for patients who, after providing adequate preoperative information, accept this type of surgery without hospitalization;

- (b)

meticulous surgical technique by surgeons trained in this type of laparoscopic approach;

- (c)

analysis and prevention of early postoperative complications;

- (d)

rigorous discharge criteria;

- (e)

strict immediate postoperative monitoring with a series of clinical checks;

- (f)

evaluation of patients’ degree of satisfaction and quality perceived.

The aim of this article is to review all the factors that currently play a fundamental role in the implementation of ALC and influence the quality and acceptance of the process, while analyzing the last 25 years since its implementation in the surgical community.

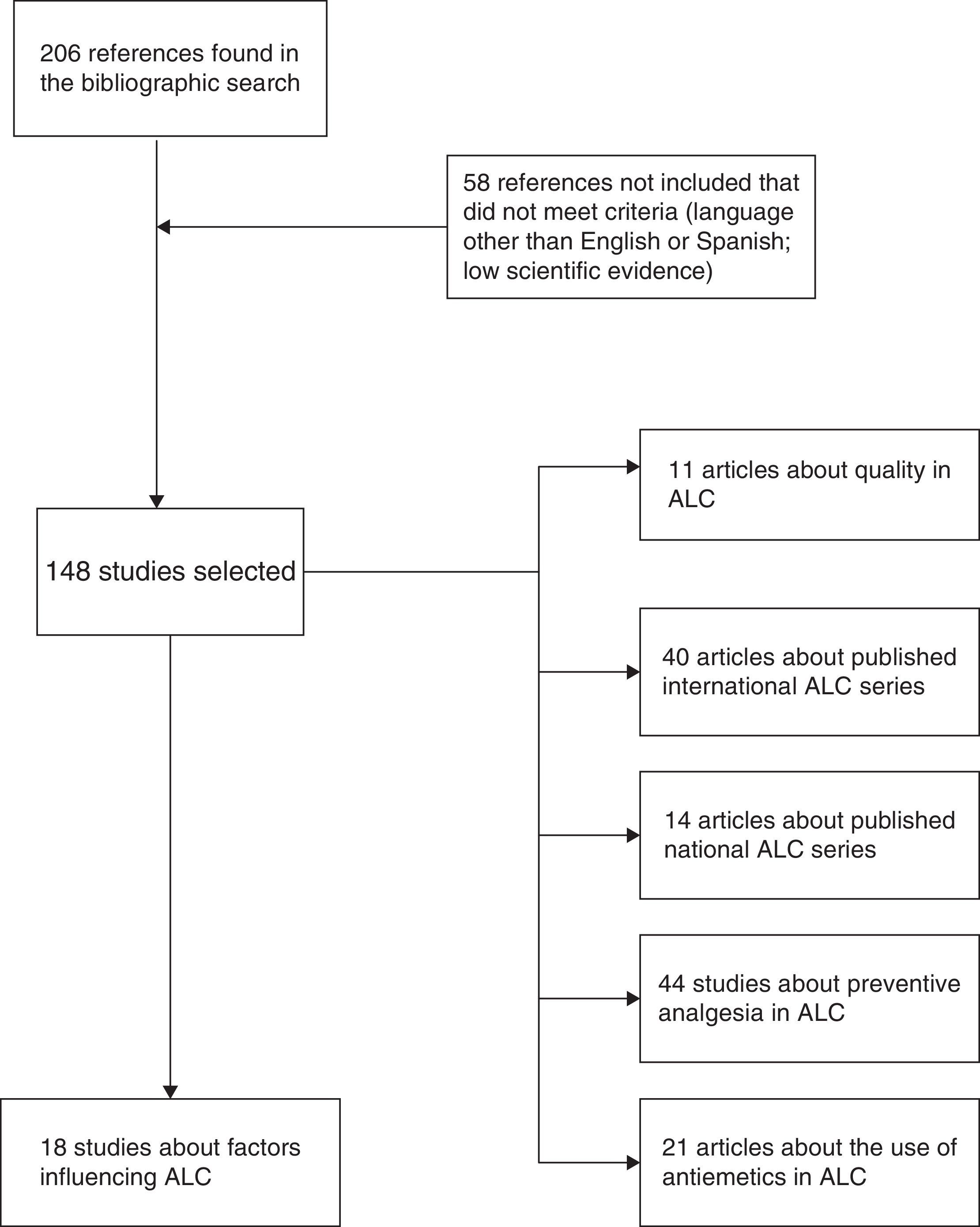

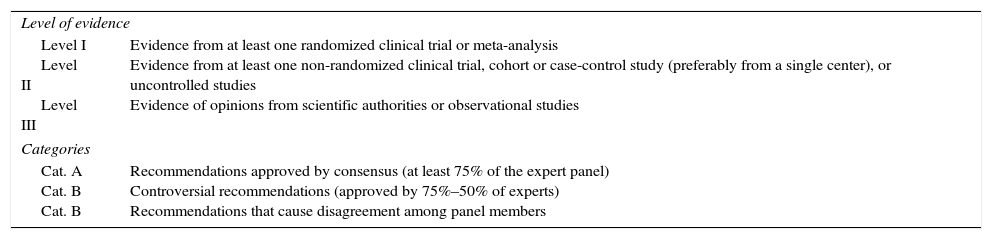

MethodsWe have carried out an electronic search on Pubmed and the Cochrane Library (January 1989–December 2014) of scientific articles (originals and reviews) in English as well as Spanish with the keywords: “laparoscopic cholecystectomy”, “outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy”, “ambulatory surgery”, “day-case laparoscopic cholecystectomy” and “ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy”. The different keyword combinations identified 206 references. We ruled out 58 articles that either did not adequately meet levels of evidence or were written in a language other than English or Spanish. In the end, we reviewed a total of 148 articles by assessing the abstracts of all the studies and thoroughly analyzing the entire article in 54 cases (Fig. 1). We have relied on the principles of evidence-based medicine to establish the levels and categories of the main recommendations in certain sections of the review (Table 1).

Levels and Categories of the Recommendations Following the Principles of Evidence-Based Medicine.

| Level of evidence | |

| Level I Level II Level III | Evidence from at least one randomized clinical trial or meta-analysis Evidence from at least one non-randomized clinical trial, cohort or case-control study (preferably from a single center), or uncontrolled studies Evidence of opinions from scientific authorities or observational studies |

| Categories | |

| Cat. A Cat. B Cat. B | Recommendations approved by consensus (at least 75% of the expert panel) Controversial recommendations (approved by 75%–50% of experts) Recommendations that cause disagreement among panel members |

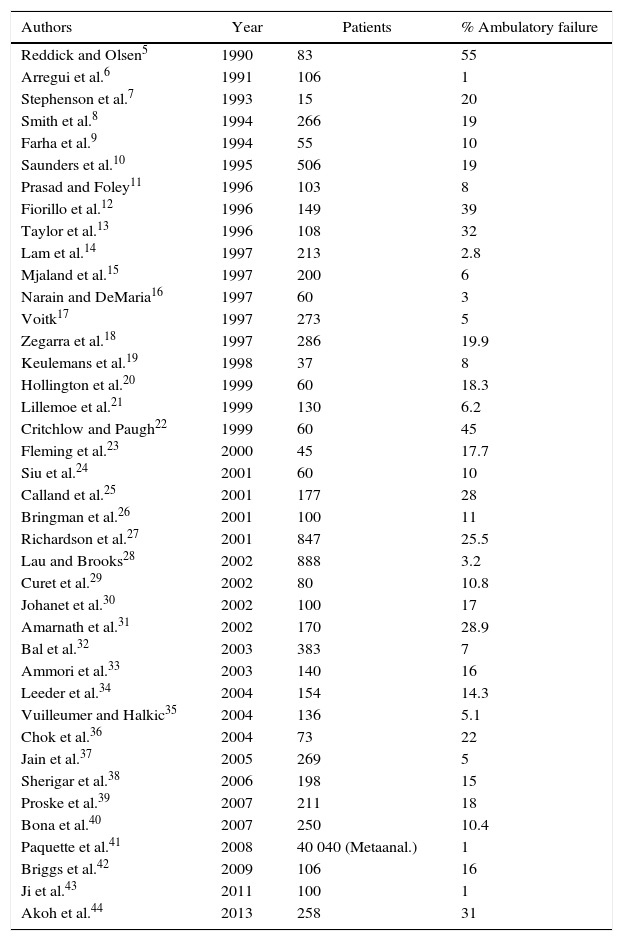

Although Muhe in Germany is considered the precursor of ALC,4 Reddick and Olsen influenced this concept in 1990 by publishing a series of 83 LC, providing the possibility for outpatient treatment in 45%, with a negligible percentage of complications.5 In successive years, numerous groups have obtained acceptable results in terms of the substitution rate (65%–99%), with a high level of reliability and safety for patients5–44 (Table 2). These results, however, show an enormous overdispersion, which is clearly indicative that the selection and process execution protocols are quite variable among different authors.

International ALC Studies Published in English.

| Authors | Year | Patients | % Ambulatory failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reddick and Olsen5 | 1990 | 83 | 55 |

| Arregui et al.6 | 1991 | 106 | 1 |

| Stephenson et al.7 | 1993 | 15 | 20 |

| Smith et al.8 | 1994 | 266 | 19 |

| Farha et al.9 | 1994 | 55 | 10 |

| Saunders et al.10 | 1995 | 506 | 19 |

| Prasad and Foley11 | 1996 | 103 | 8 |

| Fiorillo et al.12 | 1996 | 149 | 39 |

| Taylor et al.13 | 1996 | 108 | 32 |

| Lam et al.14 | 1997 | 213 | 2.8 |

| Mjaland et al.15 | 1997 | 200 | 6 |

| Narain and DeMaria16 | 1997 | 60 | 3 |

| Voitk17 | 1997 | 273 | 5 |

| Zegarra et al.18 | 1997 | 286 | 19.9 |

| Keulemans et al.19 | 1998 | 37 | 8 |

| Hollington et al.20 | 1999 | 60 | 18.3 |

| Lillemoe et al.21 | 1999 | 130 | 6.2 |

| Critchlow and Paugh22 | 1999 | 60 | 45 |

| Fleming et al.23 | 2000 | 45 | 17.7 |

| Siu et al.24 | 2001 | 60 | 10 |

| Calland et al.25 | 2001 | 177 | 28 |

| Bringman et al.26 | 2001 | 100 | 11 |

| Richardson et al.27 | 2001 | 847 | 25.5 |

| Lau and Brooks28 | 2002 | 888 | 3.2 |

| Curet et al.29 | 2002 | 80 | 10.8 |

| Johanet et al.30 | 2002 | 100 | 17 |

| Amarnath et al.31 | 2002 | 170 | 28.9 |

| Bal et al.32 | 2003 | 383 | 7 |

| Ammori et al.33 | 2003 | 140 | 16 |

| Leeder et al.34 | 2004 | 154 | 14.3 |

| Vuilleumer and Halkic35 | 2004 | 136 | 5.1 |

| Chok et al.36 | 2004 | 73 | 22 |

| Jain et al.37 | 2005 | 269 | 5 |

| Sherigar et al.38 | 2006 | 198 | 15 |

| Proske et al.39 | 2007 | 211 | 18 |

| Bona et al.40 | 2007 | 250 | 10.4 |

| Paquette et al.41 | 2008 | 40 040 (Metaanal.) | 1 |

| Briggs et al.42 | 2009 | 106 | 16 |

| Ji et al.43 | 2011 | 100 | 1 |

| Akoh et al.44 | 2013 | 258 | 31 |

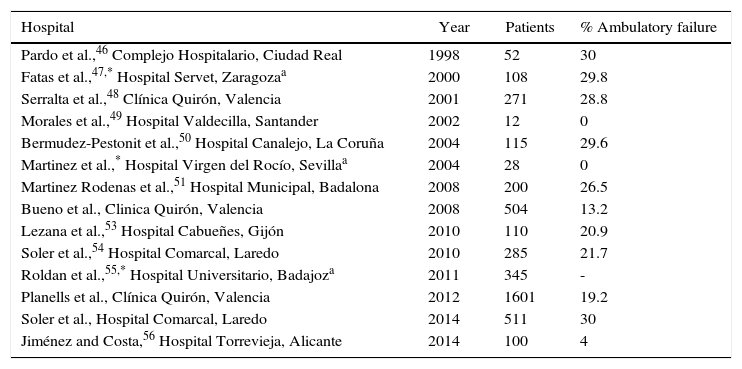

In our country, the multicenter study published in 2006 by the Spanish Association of Surgeons (AEC) to develop the clinical implementation of LC45 obtained data from 37 hospitals and 426 patients, of which only 16 (3.8%) had been operated on in a major outpatient surgery (MOS) program, which, without the added value of a national survey, was sufficiently indicative of the limited utilization of ALC. In spite of these data, certain groups (Table 3) have obtained good results in the initial series.1,3,46–57

National ALC Studies and Ambulatory Failure of the Series.

| Hospital | Year | Patients | % Ambulatory failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pardo et al.,46 Complejo Hospitalario, Ciudad Real | 1998 | 52 | 30 |

| Fatas et al.,47,* Hospital Servet, Zaragozaa | 2000 | 108 | 29.8 |

| Serralta et al.,48 Clínica Quirón, Valencia | 2001 | 271 | 28.8 |

| Morales et al.,49 Hospital Valdecilla, Santander | 2002 | 12 | 0 |

| Bermudez-Pestonit et al.,50 Hospital Canalejo, La Coruña | 2004 | 115 | 29.6 |

| Martinez et al.,* Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevillaa | 2004 | 28 | 0 |

| Martinez Rodenas et al.,51 Hospital Municipal, Badalona | 2008 | 200 | 26.5 |

| Bueno et al., Clinica Quirón, Valencia | 2008 | 504 | 13.2 |

| Lezana et al.,53 Hospital Cabueñes, Gijón | 2010 | 110 | 20.9 |

| Soler et al.,54 Hospital Comarcal, Laredo | 2010 | 285 | 21.7 |

| Roldan et al.,55,* Hospital Universitario, Badajoza | 2011 | 345 | - |

| Planells et al., Clínica Quirón, Valencia | 2012 | 1601 | 19.2 |

| Soler et al., Hospital Comarcal, Laredo | 2014 | 511 | 30 |

| Jiménez and Costa,56 Hospital Torrevieja, Alicante | 2014 | 100 | 4 |

By analyzing Tables 1 and 2, we have observed that the mean weighted percentage of failures is situated at 15.10% internationally and 20.27% in our setting. Any significant deviation from these percentages would point to poor indication or inadequate selection criteria, or, contrarily, they would mean that the results were outstanding.

In these last 3 years, there have been studies evaluating the possibility of MOS programs for single-port (SILS) laparoscopic cholecystectomy, although they have been interpreted based on overnight stays.58,59

Selection Criteria for ALC: Influential Factors in Outpatient SurgeryThe rate of unexpected hospitalizations in ALC ranges between 6% and 25%. This is principally due to the appearance of postoperative symptoms (vomiting and abdominal pain), the conversion to open surgery, and the lack of patient safety for early discharge.33,60–62 Certain preoperative and intraoperative factors have been identified that influence the possibility of outpatient surgery, which we explain below.

Preoperative Predictive FactorsPatient AgeOne of the most important independent variables for the success of outpatient surgery is age over 65, which is a predictive factor for failure in ALC.3,19,63,64 It entails a greater probability for increasing intraoperative time due to findings of complicated biliary pathology, appearance of complications from a baseline pathology, and higher rate of patient refusal to accept hospital discharge because of doubts, in spite of the information given (also known as a “social cause”).19,65,66

Two recent articles refute these asseverations and propose an acceptable rate of substitution (up to 70%) in patients over the age of 65.67,68

Finding of Acute CholecystitisGallbladder wall thickening observed on hepatobiliary ultrasound triples the probability for hospitalization after LC.61

Previous History of Complicated Biliary PathologyThe previous history of choledocholithiasis and the need for preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) does not represent a negative influencing factor. Nevertheless, the history of cholecystitis or acute pancreatitis prior to cholecystectomy has been related with the failure of ALC.5,19,66,69 This affirmation would be related with difficult dissection due to dense adhesions or hydropic gallbladder, which thereby increase the possibility of intra- and postoperative complication and interfere with early discharge.

Obese MorbidityAlthough obesity (BMI over 30) was considered an exclusion criterion,33 it currently is not an absolute contraindication, although certain problems have been attributed to the characteristics of these patients.

Previous Supramesocolic Abdominal SurgeryThis is an exclusion criterion in an ALC program because of the possibility of finding intraabdominal adhesions, entailing increased intraoperative time or the need for conversion.5,10,47,64,70

Anesthesia Risk Classification (ASA)While several authors limit the criteria to only ASA grades I and II, the option of ALC is currently open to include stable patients in ASA grades III.19,23,26,33–36,61

Oral AnticoagulationAlong general lines, these patients are not ideal for inclusion in the ALC regimen, where strict control of surgical hemostasis is necessary. Contrarily, oral antiplatelet therapy is not considered an exclusion criterion as there is better outpatient management, less morbidity and better dosage control than dicoumarol agents.71

Intraoperative Predictive FactorsSurgical TimeIn some series, surgical time is the most important predictive factor for day surgery.61 It has been established that the duration of cholecystectomy of more than 60min involves a high probability for hospitalization or overnight stay.10,17 It is therefore a multifactorial function that would include factors such as surgical difficulties for dissection, the presence of an intraoperative complication or finding of adhesions upon accessing the abdominal cavity.

A longer surgery results in prolonged anesthesia time, appearance of nausea and vomiting (N/V), and insecurities of the surgeons themselves due to the complexity of the surgery, which also influences the delayed hospital discharge.12

Surgical Team: Contribution of a Surgical Difficulty ScoreThe experience of the surgical team in the laparoscopic approach is vital in order to not unnecessarily prolong intraoperative time. A surgical dissection difficulty score was created to differentiate and classify the variables that play a key role in LC: dissection of the cystohepatic triangle, identification of the cystic duct and cystic artery, and, lastly, the dissection of the hepatic side of the gallbladder.72,73 Likewise, the term “technically difficult” LC was described. In female patients with a previous history of simple hepatic colic and ultrasound without gallbladder wall thickening, a technically simpler cholecystectomy can be expected.69

Gallbladder PerforationThis influences the increased operative time, although not the final ambulatory result.74

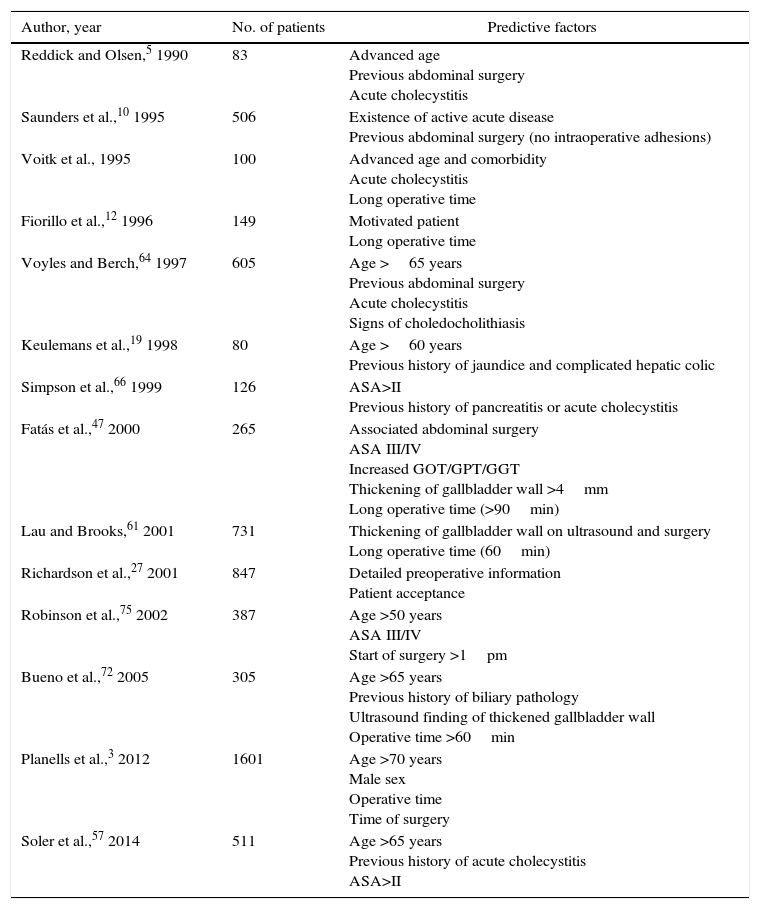

Predictive Model for the Failure of ALCThere are predictive scores based on previously analyzed preoperative variables.59,64,68,75 In general, patients younger than 65 with ASA grade I or II and no previous associated abdominal surgery, no history of acute cholecystitis and a surgical time shorter than 60min are the best candidates to be included in an ALC program (Table 4).

Predictive Factors That Negatively Influence the Success of an Outpatient LC Program.

| Author, year | No. of patients | Predictive factors |

|---|---|---|

| Reddick and Olsen,5 1990 | 83 | Advanced age Previous abdominal surgery Acute cholecystitis |

| Saunders et al.,10 1995 | 506 | Existence of active acute disease Previous abdominal surgery (no intraoperative adhesions) |

| Voitk et al., 1995 | 100 | Advanced age and comorbidity Acute cholecystitis Long operative time |

| Fiorillo et al.,12 1996 | 149 | Motivated patient Long operative time |

| Voyles and Berch,64 1997 | 605 | Age >65 years Previous abdominal surgery Acute cholecystitis Signs of choledocholithiasis |

| Keulemans et al.,19 1998 | 80 | Age >60 years Previous history of jaundice and complicated hepatic colic |

| Simpson et al.,66 1999 | 126 | ASA>II Previous history of pancreatitis or acute cholecystitis |

| Fatás et al.,47 2000 | 265 | Associated abdominal surgery ASA III/IV Increased GOT/GPT/GGT Thickening of gallbladder wall >4mm Long operative time (>90min) |

| Lau and Brooks,61 2001 | 731 | Thickening of gallbladder wall on ultrasound and surgery Long operative time (60min) |

| Richardson et al.,27 2001 | 847 | Detailed preoperative information Patient acceptance |

| Robinson et al.,75 2002 | 387 | Age >50 years ASA III/IV Start of surgery >1pm |

| Bueno et al.,72 2005 | 305 | Age >65 years Previous history of biliary pathology Ultrasound finding of thickened gallbladder wall Operative time >60min |

| Planells et al.,3 2012 | 1601 | Age >70 years Male sex Operative time Time of surgery |

| Soler et al.,57 2014 | 511 | Age >65 years Previous history of acute cholecystitis ASA>II |

Today, the safety of the ambulatory approach is still being questioned. Some would argue that there could possibly be a delay in the detection and resolution of complications. Nonetheless, the incidence of a vital complication that needs emergency treatment, such as arterial bleeding, is very low and becomes symptomatic and detected within the first few hours of post-op, while the patient is still in the hospital.76,77 After this peak of limited incidence the first few hours, most of the non-emergency complications described are detected after the first 24–48h post-op.22

One of the most extensive American multicenter studies evaluated 77604 LC performed at 4292 hospitals, with very low observed rates of vital postoperative complications, which were detected during the first 8h. However, much emphasis is given to close contact and mandatory communication between the physician and patient so that no postoperative symptoms go unnoticed.78 Therefore, a prudent observation period of 6–8h could be sufficient, as an overnight stay would not reduce the detection of vital complications.

ALC and Patient AcceptanceIndividualization is fundamental in the preoperative approach to ALC. The acceptance of the ambulatory procedure presents differences depending on the degree of information provided and the patient's age, sex and sociocultural background. The information should ensure proper postoperative management at home by the patient or family; it should be detailed in order to guarantee the maximum quality of the healthcare process, thereby avoiding the undesirable effects of lack of information, which could be the origin of an important percentage of complications not detected by the surgical team.79,80

Some patients, without really reporting any clinical reasons, opt to remain hospitalized for 24h, in spite of having received preoperative information and accepted inclusion in the outpatient program. This so-called “social” cause is a factor that significantly increases the percentage of unexpected hospitalizations in an MOS program. It cannot be predicted, even in spite of the information given.1

ALC and Postoperative VomitingN/V after LC present an overall incidence close to 12%–52% and can prolong patient stay in an intermediate care unit by 56%, with the resulting delay or impossibility for outpatient discharge.81,82 This problem is multifactorial and influenced by patients’ characteristics and baseline diseases, as well as the susceptibility of each individual. Several factors have been found in association with the appearance of N/V after LC83:

- (a)

Anesthetic factors: the use of opiate derivatives, as well as the use of inhaled anesthetic agents in anesthetic induction, favor the appearance of N/V after surgery. The use of propofol, administration of supplementary oxygen 2h after surgery, maintained correct hydration, reduced use of neostigmine and opiate compounds all reduce the appearance of postoperative N/V (Level of evidence I, cat. A).84

- (b)

Surgical factors: we should emphasize the negative effect of CO2 insufflation pressure above 13mmHg, as well as the residual gas trapped once the surgery is concluded.85

- (c)

Postoperative factors: the presence of postoperative pain or premature mobilization could stimulate emesis after LC.86

Inter-individual variability in postoperative abdominal pain is characteristic after LC. Some 33%–50% of patients suffer severe pain the same day of the operation, which requires analgesia and is responsible for overnight stays the day of the surgical intervention in 24%–41% of patients.12,87,88

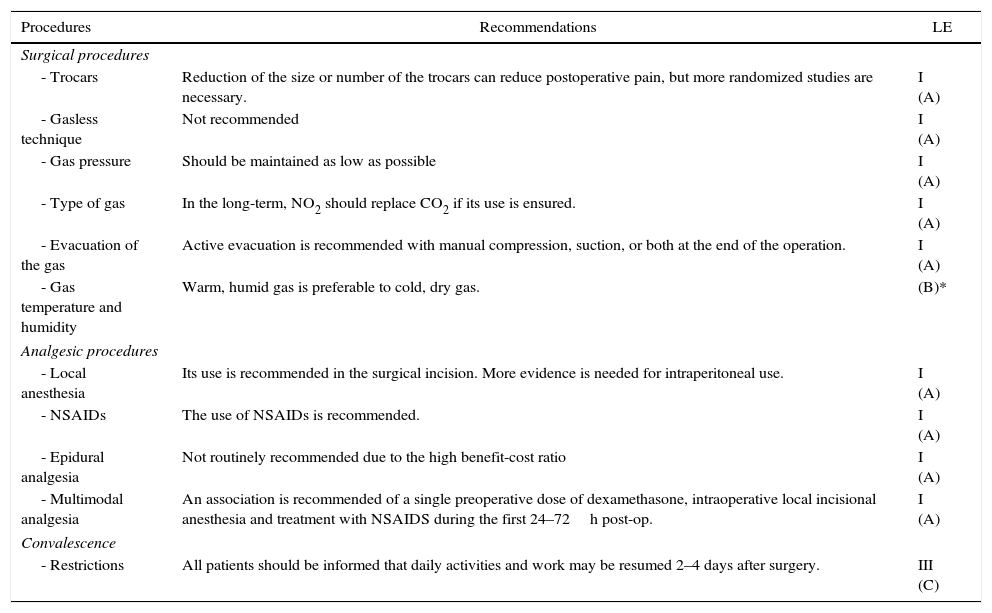

It has been demonstrated that the umbilical port site is the most frequent location of parietal pain, although the visceral component is most important during the first 48h post-op.89Table 5 shows several measures to reduce postoperative pain after LC, following criteria of evidence-based medicine.

Prevention of Abdominal Pain After Laparoscopy; Recommendations Based on Evidence-Based Medicine.

| Procedures | Recommendations | LE |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical procedures | ||

| - Trocars | Reduction of the size or number of the trocars can reduce postoperative pain, but more randomized studies are necessary. | I (A) |

| - Gasless technique | Not recommended | I (A) |

| - Gas pressure | Should be maintained as low as possible | I (A) |

| - Type of gas | In the long-term, NO2 should replace CO2 if its use is ensured. | I (A) |

| - Evacuation of the gas | Active evacuation is recommended with manual compression, suction, or both at the end of the operation. | I (A) |

| - Gas temperature and humidity | Warm, humid gas is preferable to cold, dry gas. | (B)* |

| Analgesic procedures | ||

| - Local anesthesia | Its use is recommended in the surgical incision. More evidence is needed for intraperitoneal use. | I (A) |

| - NSAIDs | The use of NSAIDs is recommended. | I (A) |

| - Epidural analgesia | Not routinely recommended due to the high benefit-cost ratio | I (A) |

| - Multimodal analgesia | An association is recommended of a single preoperative dose of dexamethasone, intraoperative local incisional anesthesia and treatment with NSAIDS during the first 24–72h post-op. | I (A) |

| Convalescence | ||

| - Restrictions | All patients should be informed that daily activities and work may be resumed 2–4 days after surgery. | III (C) |

The incidence of characteristic shoulder-tip pain varies from 30% to 50% after LC. It is usually short in duration and not often intense, with a peak around 24–48h after laparoscopy.90,91 It has been demonstrated that insufflation pressure below 10mmHg, evacuation of residual gas and instillation of local anesthesia in the work area significantly reduce pain intensity and frequency (Level of evidence I, cat. A).92,93

ALC and Learning CurveIt is strictly necessary for the surgical technique to be performed by expert surgeons with experience in laparoscopic management and outpatient surgery.94 This expertise is reflected in the reduced intraoperative and anesthesia times, lower probability of conversion to open surgery and development of intraoperative complications or, if they appear, the ability to safely resolve them without the need for conversion to conventional surgery.95

Factors That Favor Outpatient LCALC programs have been boosted by the development of fast track anesthesia and multimodal analgesia, which provide anesthesia and surgical interventions with rapid patient recovery.

Fast Track Anesthesia TechniqueThe role of this anesthesia technique is observed in series published at the end of the 1990s, which showed evidence of the fundamental role of propofol as an anesthetic agent (Level of evidence I, cat. A).96 Other contributors are compositions like desflurane, isoflurane or sevoflurane, the latter of which especially favors rapid post-anesthesia recovery and easier regression from the state of sedation.97,98

Today, one of the keys of balanced multimodal anesthesia is the minimal use of analgesia with opiates. The recent emergence of opiate compositions with similar pharmacokinetic characteristics, such as alfentanil and remifentanil, and even the association with ketamine, provides short-acting analgesia (Level of evidence I, cat. A).99,100

Depolarizing drugs like neostigmine or prostigmin are known to increase the incidence of postoperative N/V. Rocuronium, a moderate-duration non-depolarizing muscle relaxant, is the agent of choice as it provides good conditions for intubation, good hemodynamic stability and rapid recovery.101

Preventive AnalgesiaThe infiltration or instillation of local anesthesia before and during laparoscopic exploration provides the patient with less postoperative pain, requiring a lower dose of analgesia and a more rapid recovery of daily activities than those patients who do not receive preventive analgesia (Level of evidence I, cat. A).94,102

Although there are contradictory results about the analgesic effect of the intraperitoneal instillation of anesthetic agents, 2 recent meta-analyses recommend the systematic use of 0.5% bupivacaine in the hepatic site after dissection and before aspiration of the pneumoperitoneum (Level of evidence I, cat. B).90,91,96,103,104 The analgesia needs are significantly lower in patients with administration of anesthesia in the LC port site wounds, and more effective in pre-incisional than post-incisional administration (Level of evidence I, cat. A).105–109

Use of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDS)NSAIDS administered intravenously significantly reduced pain after LC compared to a control group.110 Ibuprofen, dexketoprofen trometamol and ketorolac can be useful alternatives to fentanyl, reducing the undesirable effects compared to the opiate when used in the postoperative therapy of the first 24–72h after LC (Level of evidence I, cat. A).111–113

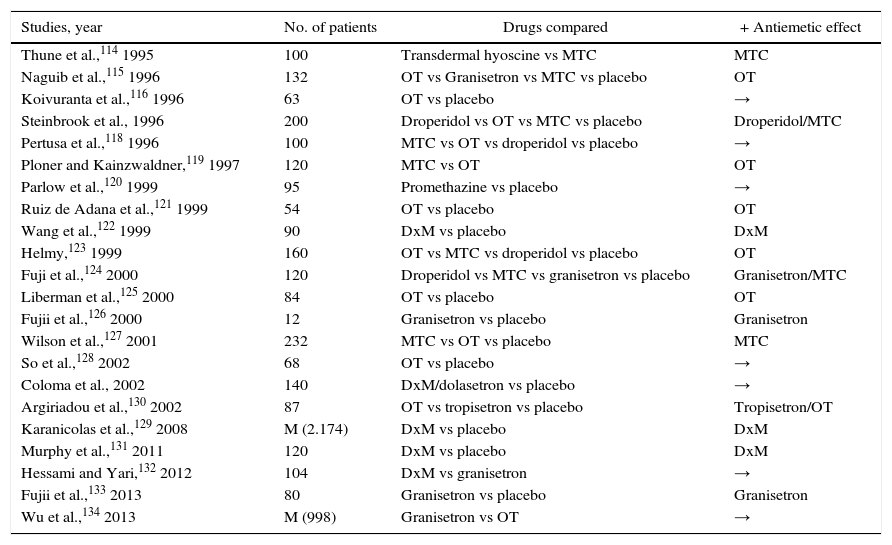

Antiemetic TherapyAlthough clinical trials have been published with great variability and disparity of results, the introduction of ondansetron (OT) years ago has caused a revolution in the anesthetic and postoperative management of ALC114–134 (Table 6).

Clinical Trials That Compare the Success Rate of Certain Compounds Used in Antiemetic Prophylaxis After LC.

| Studies, year | No. of patients | Drugs compared | + Antiemetic effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thune et al.,114 1995 | 100 | Transdermal hyoscine vs MTC | MTC |

| Naguib et al.,115 1996 | 132 | OT vs Granisetron vs MTC vs placebo | OT |

| Koivuranta et al.,116 1996 | 63 | OT vs placebo | → |

| Steinbrook et al., 1996 | 200 | Droperidol vs OT vs MTC vs placebo | Droperidol/MTC |

| Pertusa et al.,118 1996 | 100 | MTC vs OT vs droperidol vs placebo | → |

| Ploner and Kainzwaldner,119 1997 | 120 | MTC vs OT | OT |

| Parlow et al.,120 1999 | 95 | Promethazine vs placebo | → |

| Ruiz de Adana et al.,121 1999 | 54 | OT vs placebo | OT |

| Wang et al.,122 1999 | 90 | DxM vs placebo | DxM |

| Helmy,123 1999 | 160 | OT vs MTC vs droperidol vs placebo | OT |

| Fuji et al.,124 2000 | 120 | Droperidol vs MTC vs granisetron vs placebo | Granisetron/MTC |

| Liberman et al.,125 2000 | 84 | OT vs placebo | OT |

| Fujii et al.,126 2000 | 12 | Granisetron vs placebo | Granisetron |

| Wilson et al.,127 2001 | 232 | MTC vs OT vs placebo | MTC |

| So et al.,128 2002 | 68 | OT vs placebo | → |

| Coloma et al., 2002 | 140 | DxM/dolasetron vs placebo | → |

| Argiriadou et al.,130 2002 | 87 | OT vs tropisetron vs placebo | Tropisetron/OT |

| Karanicolas et al.,129 2008 | M (2.174) | DxM vs placebo | DxM |

| Murphy et al.,131 2011 | 120 | DxM vs placebo | DxM |

| Hessami and Yari,132 2012 | 104 | DxM vs granisetron | → |

| Fujii et al.,133 2013 | 80 | Granisetron vs placebo | Granisetron |

| Wu et al.,134 2013 | M (998) | Granisetron vs OT | → |

DxM: dexamethasone; M: meta-analysis; MTC: metoclopramide; OT: ondansetron; →: no significant difference among compounds.

Different work groups have shown excellent results with the administration of OT and granisetron to reduce N/V after ALC (Level of evidence I, cat. A). They recommend the systematic administration of dexamethasone (8mg iv) before induction as a more effective measure to reduce the incidence of N/V (Level of evidence I, cat. A).125–130

Quality Perceived in ALCThe evaluation of the quality of care associated with ambulatory treatment should be included in the analysis of the safety, efficacy and satisfaction of the patient.81,135,136

Need for Patient Satisfaction SurveysThis is an essential condition to evaluate the objectives set for these last 25 years. Results of the ambulatory process should be analyzed to respond to patient needs and expectations after determining the degree of perceived satisfaction. The degree of acceptance manifested by ALC patients ranges from 60% to 95%.15,19,21,24,25,27,137

Patient dissatisfaction, which is very low according to the series, can be correlated with variables such as time transpired between admission to hospital and surgery, time between surgery and discharge, and amount of pain experienced.138 Therefore, important questions that are still being debated are the best time for the perceived quality survey, and whether this should be anonymous or not.20,21,33,35

We have observed a significantly lower percentage of failures in ALC programs that establish preoperative protocols for patient information and address several aspects related with the acceptance of early discharge after surgery.27,139–141 In our country, few series have published results about the acceptance of the process after a postoperative survey. This percentage ranges from 85% to 98%, although we should add that up to 19% of patients indicated that they felt that discharge was either too premature or unsafe because they had not been hospitalized.3,51,63,142

Postoperative Follow-upThere are several modalities for the postoperative follow-up of ALC. Some groups make patient house calls in cases with persistent pain in the first few days after surgery,20,143 while other make a series of follow-up telephone calls the first 3 weeks after the procedure.23,31 Most studies concur that optimal postoperative management involves initial contact the same night or morning after surgery (which is basically done by the home hospitalization unit) and later scheduled outpatient follow-up visits between the first and second weeks post-op and then one month after cholecystectomy.12,21,26,35,48

ConclusionsALC represents the present and future of uncomplicated cholelithiasis treatment as it can be done with good results, safely, with low morbidity and a high level of patient satisfaction. Individualization of the process is essential. Factors that ensure a high level of success are strict patient selection and surgical teams with experience in LC. Likewise, we believe that the leadership and decision-making process, as well as the performance of the surgical intervention itself, should be organized by surgical groups and not determined by the politico-economic situation. Decisions that would modify fundamental aspects of the process should not be made outside of the surgical setting.

ALC should be a key objective in surgical units, especially in this day and age when so many measures of uncertain efficacy are being proposed to sustain the Spanish national healthcare system.

Conflict of InterestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Bueno Lledó J, Granero Castro P, Gomez i Gavara I, Ibañez Cirión JL, López Andújar R, García Granero E. Veinticinco años de colecistectomía laparoscópica en régimen ambulatorio. Cir Esp. 2016;94:429–441.