Acute abdomen is a rare entity in the pregnant patient, with an incidence of one in 500–635 patients. Its appearance requires a quick response and an early diagnosis to treat the underlying disease and prevent maternal and foetal morbidity. Imaging tests are essential, due to clinical and laboratory masking in this subgroup. Appendicitis and complicated biliary pathology are the most frequent causes of non-obstetric acute abdomen in the pregnant patient. The decision to operate, the timing, and the surgical approach are essential for a correct management of this pathology. The aim of this paper is to perform a review and update on the diagnosis and treatment of non-obstetric acute abdomen in pregnancy.

En la paciente embarazada, el abdomen agudo es una entidad infrecuente, cuya incidencia es de una por cada 500-635 gestantes. Pero su aparición requiere una respuesta rápida y un diagnóstico temprano para tratar la enfermedad de base y evitar la morbimortalidad maternofetal. Las pruebas de imagen son fundamentales para ello, dado el enmascaramiento clínico y analítico en estas pacientes. La apendicitis y la enfermedad biliar complicada son las causas más frecuentes de abdomen agudo no obstétrico. La decisión de intervenir, la elección del momento y la vía de abordaje son esenciales para un correcto manejo de esta dolencia. El objetivo de esta publicación es realizar una revisión y puesta al día sobre el diagnóstico y tratamiento del abdomen agudo de origen no obstétrico en la paciente gestante.

In pregnant patients with any type of condition requiring surgery that does not affect the well-being of the mother or foetus, it is commonly accepted that surgery should be postponed until after childbirth.1 Some 0.2%–1% of expectant mothers, however, will require non-obstetric surgical interventions.2–4 The incidence of acute abdomen during pregnancy is one out of every 500–635 pregnancies2; acute appendicitis and complicated biliary disease are the 2 most frequent surgical emergencies.3

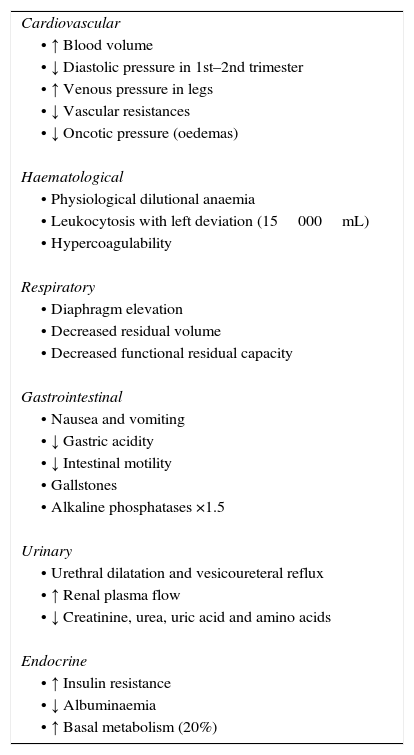

Gestation causes anatomical and physiological variations to women's bodies, which can result in atypical clinical manifestations of acute abdomen. As the gestational period progresses, the uterus increases in size: it is considered intraabdominal in the 12th week and umbilical in the 20th. Consequently, this modifies the normal distribution of the surrounding intraabdominal organs. The expanding uterus makes it difficult to locate pain points and could disguise pain intensity.4 The main physiological changes are summarised in Table 1.5 Meanwhile, the high prevalence of nausea, vomiting and abdominal discomfort in obstetric populations, together with the habitual indecision as whether to perform imaging tests, create difficulties in the evaluation of these patients.2,4

Physiological Changes During Pregnancy.5

| Cardiovascular |

| • ↑ Blood volume |

| • ↓ Diastolic pressure in 1st–2nd trimester |

| • ↑ Venous pressure in legs |

| • ↓ Vascular resistances |

| • ↓ Oncotic pressure (oedemas) |

| Haematological |

| • Physiological dilutional anaemia |

| • Leukocytosis with left deviation (15000mL) |

| • Hypercoagulability |

| Respiratory |

| • Diaphragm elevation |

| • Decreased residual volume |

| • Decreased functional residual capacity |

| Gastrointestinal |

| • Nausea and vomiting |

| • ↓ Gastric acidity |

| • ↓ Intestinal motility |

| • Gallstones |

| • Alkaline phosphatases ×1.5 |

| Urinary |

| • Urethral dilatation and vesicoureteral reflux |

| • ↑ Renal plasma flow |

| • ↓ Creatinine, urea, uric acid and amino acids |

| Endocrine |

| • ↑ Insulin resistance |

| • ↓ Albuminaemia |

| • ↑ Basal metabolism (20%) |

The objective of this study is to review the most frequent causes of non-obstetric acute abdomen during pregnancy, with an emphasis on the diagnostic and therapeutic tools currently available. We conducted a bibliographic search of the literature in PubMed, using the keywords “acute abdomen”, “pregnancy”, “non-obstetric”, “imaging”, “diagnosis” and “treatment”, as well as several combinations of these terms. The definitive list of articles was chosen after having read the abstracts, at which time we selected those that were relevant for this review.

Diagnostic Imaging in Pregnant Patients With Acute AbdomenDiagnostic problems in expectant mothers with acute abdomen are derived from the modifications in the baseline conditions of these patients, as previously stated. In addition to hyperthermia and functional leukocytosis, physical examination of the abdomen is made difficult by the progressive displacement of the intraabdominal organs with the expansion of the uterus, as occurs with the appendix.6

There is controversy about which diagnostic imaging test is ideal for pregnant patients with an acute abdomen. The risks and benefits of each of the methods should always be considered. There are 2 fundamental principles that should govern these cases. The first was coined by Cope in 1921: “Earlier diagnosis means better prognosis”.6 The second states that the first option is to always select the method that exposes the foetus to the lowest possible dose of radiation.4

UltrasoundDue to both its efficacy and innocuity,3,7,8 ultrasound is universally accepted as the technique of choice in pregnancy and is, therefore, the first radiological examination done. It also provides elevated sensitivity and specificity in cases of acute abdomen, especially cholecystitis and appendicitis.2,3 Nonetheless, the efficacy of this test diminishes after week 32 because of the technical difficulties secondary to uterine growth. Moreover, appendiceal perforation can reduce the sensitivity of the test to 28.5%, which contrasts with the finding of non-complicated appendicitis (80.5%), or appendiceal adhesions (89%).9 If a diagnosis cannot be reached with ultrasound, the following step is to order other diagnostic imaging studies.

Magnetic Resonance ImagingMagnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an excellent diagnostic tool that presents a sensitivity and specificity of 91% and 85%, respectively.10 Since the advent of this technique, many studies have been done on pregnant women and there have been no demonstrated adverse effects on foetuses.7,8,11–14 Some authors have hypothesised about the noise, which could cause stress and excessive movement of the foetus, thereby affecting the quality of the images. This risk seem to be more theoretical than real.12,14,15

MRI surpasses some of the limitations of ultrasound, mainly those caused by the size of a pregnant uterus.8 As for the use of intravenous contrast with gadolinium, even though there have been no reported adverse effects after its administration,13,14 it is classified as category C by the US Food and Drug Administration, so its use should therefore be relegated to cases where it is considered essential and after having discussed the case with the radiologist and the risks and benefits with the patient.3,15,16

The main advantage of this test is that it does not subject the patient or the foetus to radiation. On the other hand, it is a test that is not available at all hospitals, nor is it always readily available. It is expensive and not always well tolerated due to the possible claustrophobic sensation and the discomfort generated by the noise.

Computed TomographyComputed tomography (CT) usually reaches better diagnostic levels than ultrasound and MRI. It presents a sensitivity and specificity of up to 93% in cases of acute abdomen,17 although it poses the problem of the risk of malformations and carcinogenesis.

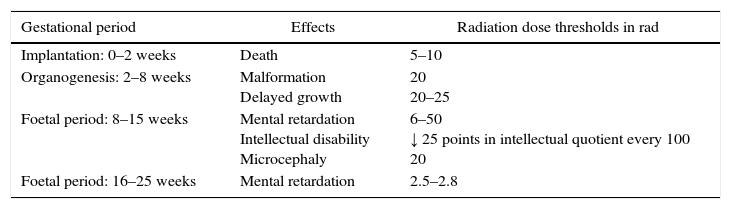

The well-known effects of radiation on the foetus, especially in the first weeks of gestation, make most physicians uncomfortable about its use in pregnant patients. Nonetheless, the literature does not support these fears. Estimated data for radiation dose thresholds and possible effects on the foetus in different stages of development are presented in Table 2.4 The accumulated radiation dose is the main risk factor, but the gestational age is also important.17,18 Foetal mortality rates are higher when the exposure occurs within the first week of conception.3 Furthermore, the ionising radiation could eventually increase the risk for the development of haematologic neoplasias in childhood.3,19 It has been indicated that the risk of malformations is insignificant at 5rad or less and that the risk for malformation significantly increases at doses above 15rad.4 It has therefore been recommended that the accumulated radiation dose in the embryo during pregnancy should be less than 5–10rad, and that no single diagnostic study should exceed 5rad.3,17 The typical exposure level for a CT scan is 2.5rad.4,20

Effects of Ionising Radiation on the Foetus in Different Stages of Development.

| Gestational period | Effects | Radiation dose thresholds in rad |

|---|---|---|

| Implantation: 0–2 weeks | Death | 5–10 |

| Organogenesis: 2–8 weeks | Malformation Delayed growth | 20 20–25 |

| Foetal period: 8–15 weeks | Mental retardation Intellectual disability Microcephaly | 6–50 ↓ 25 points in intellectual quotient every 100 20 |

| Foetal period: 16–25 weeks | Mental retardation | 2.5–2.8 |

Thus, the use of CT is justified to make an early diagnosis, but only in cases of unclear diagnosis after ultrasound or if it is impossible to do an MRI.7,8,21 One CT scan in a pregnant patient does not exceed the radiation dose established as the safety threshold and can, in uncertain situations, avoid a delay in diagnosis that could be fatal for maternal/foetal prognosis.7,8,21

Simple Abdominal RadiographGiven the greater efficacy of the aforementioned imaging tests, X-rays are currently not often used in the diagnosis of acute abdomen. They are useful, however, in cases of suspected obstruction, especially if caused by adhesions. Simple radiography can be used both for diagnosis as well as follow-up by spacing out the repetition of the test by several hours in order to observe the improvement, if any, of the radiological signs of obstruction. An abdominal X-ray involves a radiation exposure of 0.325rad.20

Surgical Treatment of Pregnant Patients With Acute AbdomenThe reason for the use of all the diagnostic tests available, including CT scan, is the evidence of worsening foetal prognosis as the intraabdominal infection advances. A delay in diagnosis is considered malpraxis as it would delay any possible indication for surgery. There are extensive and diverse reports in the literature about the time at which surgery should be indicated, anaesthesia risks and the choice of approach according to the weeks of gestation.

In general terms, we should avoid surgical interventions in expectant mothers.22–24 Although a greater incidence of malformations or miscarriages has not been demonstrated, there does seem to be more newborns with low birth weight as well as sudden infant deaths within the first 4 months of life.23,24 Contrarily, other authors defend the use of diagnostic laparoscopy, which they justify as a reasonable alternative to ionising radiation as it provides the ability to treat the patient at the time of diagnosis.25

There are several considerations to keep in mind during the intra- and postoperative management of pregnant patients when there is a need for emergency surgery. It is recommended to place the patient in a slightly left lateral decubitus position, which avoids compression of the uterus on the vena cava and, therefore, a drop in venous return that could result in hypotension in the mother and foetus. Thromboembolic prophylaxis is necessary because of the thrombophilic tendency of pregnancy itself. Compressive measures of the lower extremities and heparin are recommended by most specialists, as well as foetal monitoring and maternal capnography.3,22,26–34

Laparoscopic ApproachInitially, laparoscopy was contraindicated in pregnant patients, based on the risk for foetal hypoperfusion due to uterine compression caused by the pressure induced by intraabdominal CO2.3 Nonetheless, as surgeons gained experience in laparoscopic techniques, this fear diminished.25,35–37 In the 1990s, Gurbuz et al.35 presented their results of the treatment of non-obstetric abdominal pain during pregnancy, which concluded that laparoscopy is a safe technique that can be done at any time during pregnancy without any additional risk to the foetus in patients requiring urgent surgery. Reedy et al.25 compared the perinatal results of 2233 laparoscopies and 2491 laparotomies in pregnant women over a period of 20 years. Most of the surgeries were done during the first trimester. Their results showed a greater risk for low birth weight and premature labour in patients who had undergone surgery when compared with the national registry of full-term pregnancies without surgical intervention, but no differences were found in the rates of malformations or miscarriages. When the results were compared between the two approaches in the case of surgically treated patients, no significant differences were found for foetal morbidity either. In 2010, Corneille et al.38 presented a review of 94 pregnancies with surgery for non-obstetric acute abdomen (mainly cholecystitis and appendicitis): 53 underwent laparoscopy and 41 laparotomy. The authors concluded that both approaches presented similar results for morbidity and mortality and that the perinatal complications were independent of the technique employed. Disease severity was the factor with the greatest influence on prognosis.

Another subject for debate is the indication of the approach according to gestational age. Although it has been accepted that the second trimester is the best to reduce complications, other series demonstrate that laparoscopic surgery can be done during any trimester, with very low rates of maternal and foetal morbidity.3,25,27,28

As for the access to the abdominal cavity, although both the open (Hasson trocar) as well as the closed techniques (Veress needle) have been described as safe,1,3,26,28 there have been reports of cases with uterine injury using the closed technique.34 Open access therefore seems more recommendable.2,3,31

The CO2 used to create pneumoperitoneum is usually at pressure levels of 13–14mmHg in non-obstetric patients. During pregnancy, a gas pressure of 8–12mmHg avoids uterine hypoperfusion and maternal pulmonary complications3; some series, however, have demonstrated that the use of pressures of up to 15mmHg caused no injury to the mother or foetus.26,27

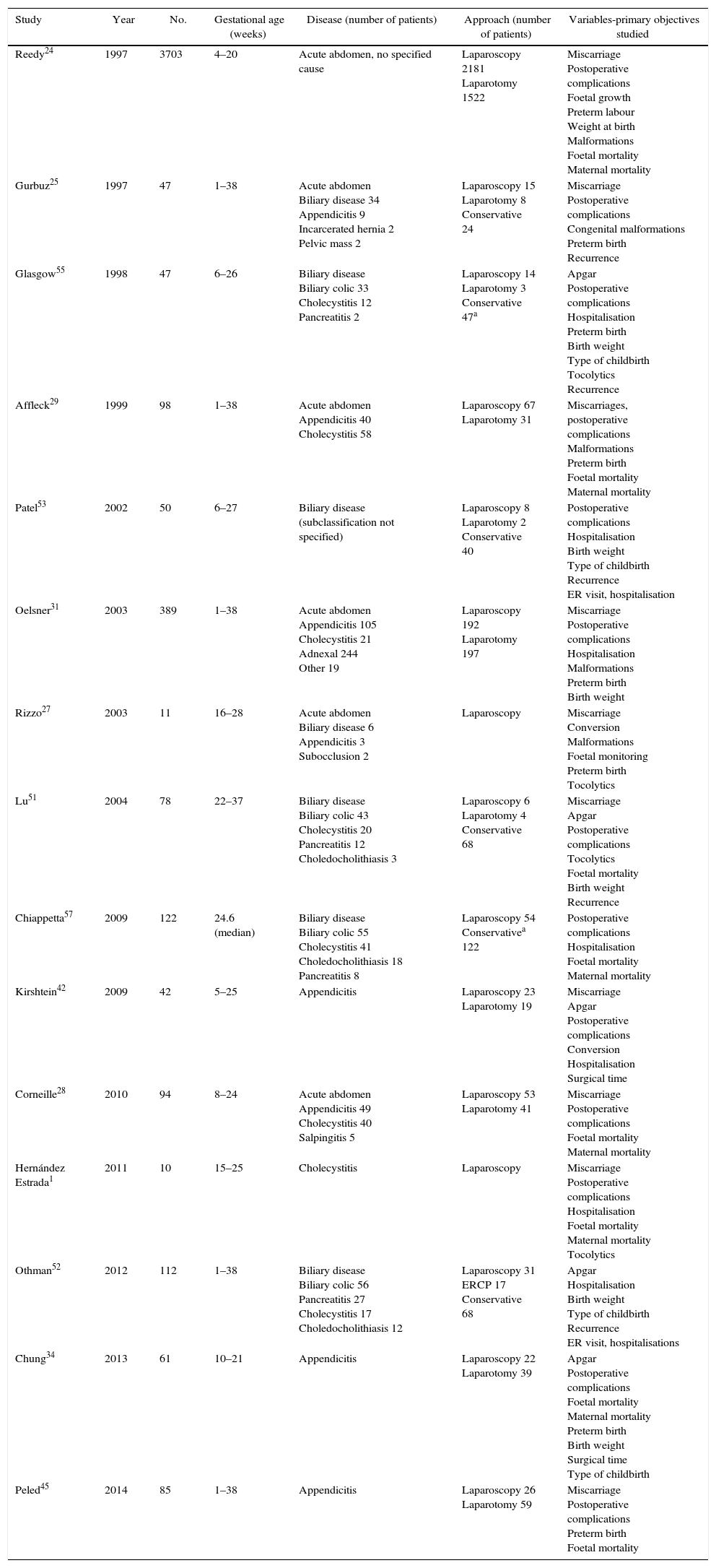

Most Frequent Causes of Non-obstetric Acute Abdomen in Pregnant PatientsTable 3 compares studies of pregnant women with non-obstetric acute abdomen. The most common causes are acute appendicitis and biliary disease, followed by bowel obstruction. With lower prevalence and in decreasing order of frequency, other causes include hernias, inflammatory bowel diseases, perforated ulcers, intraabdominal bleeding, tumours and abdominal pain of unknown aetiology. We will focus the remainder of this review on the 2 most prevalent causes.

Comparison of Studies in Pregnant Women With Non-obstetric Acute Abdomen.

| Study | Year | No. | Gestational age (weeks) | Disease (number of patients) | Approach (number of patients) | Variables-primary objectives studied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reedy24 | 1997 | 3703 | 4–20 | Acute abdomen, no specified cause | Laparoscopy 2181 Laparotomy 1522 | Miscarriage Postoperative complications Foetal growth Preterm labour Weight at birth Malformations Foetal mortality Maternal mortality |

| Gurbuz25 | 1997 | 47 | 1–38 | Acute abdomen Biliary disease 34 Appendicitis 9 Incarcerated hernia 2 Pelvic mass 2 | Laparoscopy 15 Laparotomy 8 Conservative 24 | Miscarriage Postoperative complications Congenital malformations Preterm birth Recurrence |

| Glasgow55 | 1998 | 47 | 6–26 | Biliary disease Biliary colic 33 Cholecystitis 12 Pancreatitis 2 | Laparoscopy 14 Laparotomy 3 Conservative 47a | Apgar Postoperative complications Hospitalisation Preterm birth Birth weight Type of childbirth Tocolytics Recurrence |

| Affleck29 | 1999 | 98 | 1–38 | Acute abdomen Appendicitis 40 Cholecystitis 58 | Laparoscopy 67 Laparotomy 31 | Miscarriages, postoperative complications Malformations Preterm birth Foetal mortality Maternal mortality |

| Patel53 | 2002 | 50 | 6–27 | Biliary disease (subclassification not specified) | Laparoscopy 8 Laparotomy 2 Conservative 40 | Postoperative complications Hospitalisation Birth weight Type of childbirth Recurrence ER visit, hospitalisation |

| Oelsner31 | 2003 | 389 | 1–38 | Acute abdomen Appendicitis 105 Cholecystitis 21 Adnexal 244 Other 19 | Laparoscopy 192 Laparotomy 197 | Miscarriage Postoperative complications Hospitalisation Malformations Preterm birth Birth weight |

| Rizzo27 | 2003 | 11 | 16–28 | Acute abdomen Biliary disease 6 Appendicitis 3 Subocclusion 2 | Laparoscopy | Miscarriage Conversion Malformations Foetal monitoring Preterm birth Tocolytics |

| Lu51 | 2004 | 78 | 22–37 | Biliary disease Biliary colic 43 Cholecystitis 20 Pancreatitis 12 Choledocholithiasis 3 | Laparoscopy 6 Laparotomy 4 Conservative 68 | Miscarriage Apgar Postoperative complications Tocolytics Foetal mortality Birth weight Recurrence |

| Chiappetta57 | 2009 | 122 | 24.6 (median) | Biliary disease Biliary colic 55 Cholecystitis 41 Choledocholithiasis 18 Pancreatitis 8 | Laparoscopy 54 Conservativea 122 | Postoperative complications Hospitalisation Foetal mortality Maternal mortality |

| Kirshtein42 | 2009 | 42 | 5–25 | Appendicitis | Laparoscopy 23 Laparotomy 19 | Miscarriage Apgar Postoperative complications Conversion Hospitalisation Surgical time |

| Corneille28 | 2010 | 94 | 8–24 | Acute abdomen Appendicitis 49 Cholecystitis 40 Salpingitis 5 | Laparoscopy 53 Laparotomy 41 | Miscarriage Postoperative complications Foetal mortality Maternal mortality |

| Hernández Estrada1 | 2011 | 10 | 15–25 | Cholecystitis | Laparoscopy | Miscarriage Postoperative complications Hospitalisation Foetal mortality Maternal mortality Tocolytics |

| Othman52 | 2012 | 112 | 1–38 | Biliary disease Biliary colic 56 Pancreatitis 27 Cholecystitis 17 Choledocholithiasis 12 | Laparoscopy 31 ERCP 17 Conservative 68 | Apgar Hospitalisation Birth weight Type of childbirth Recurrence ER visit, hospitalisations |

| Chung34 | 2013 | 61 | 10–21 | Appendicitis | Laparoscopy 22 Laparotomy 39 | Apgar Postoperative complications Foetal mortality Maternal mortality Preterm birth Birth weight Surgical time Type of childbirth |

| Peled45 | 2014 | 85 | 1–38 | Appendicitis | Laparoscopy 26 Laparotomy 59 | Miscarriage Postoperative complications Preterm birth Foetal mortality |

ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Appendicitis is the most frequent cause of non-obstetric acute abdomen in pregnant women. The general prevalence is reportedly one for every 1500 pregnancies.39,40 Out of the total of acute appendix episodes, 40% appear during the second trimester of gestation.2,41

The location of the appendix may or may not be influenced by the expanding uterus, depending on the attachment of the caecum. If the appendix is retrocaecal, the displacement of the caecal pole may cause atypical symptoms, such as flank or dorsal pain, which may be confused with infection of the urinary tract or pyelonephritis.2

Pregnancy is not a risk factor for appendicitis. Nonetheless, pregnancy is associated with a higher rate of appendiceal perforation, which can reach 43%,4,38,42 which contrasts with the 19% observed in the general population.31,43 Foetal mortality is closely linked to perforation rates.2 Foetal loss rates with appendiceal perforation reach 20%–35%, which contrasts with 1.5% in cases of non-complicated appendicitis. It has been demonstrated that more than half of perforations occur due to diagnostic delay, which emphasises the importance of utilising the imaging tests necessary to reach a diagnosis. Thus, the rate of perforations is 66% in patients in whom the surgical delay is greater than 24h, while they practically do not exist in patients treated with surgery in the first 24h after the onset of symptoms.2 In addition to symptoms and laboratory testing,2–4 imaging studies are essential. Ultrasound should be done initially. If it is not conclusive, MRI can be used or even CT if necessary, but under no circumstance should the diagnosis be delayed for fear of ionising radiation.

Pregnant women with a diagnosis of appendicitis should be operated on immediately, regardless of the gestational age.31,44 Prospective studies have demonstrated that laparoscopy is the approach of choice as it provides the advantages of rapid recovery and less postoperative pain; it has become established as a safe and effective technique.3,26,27,31,43,45,46

Complicated Biliary DiseasePregnancy is a situation prone to lithogenesis as a consequence of the hormonal changes and the delayed gallbladder emptying that these patients present.2,47,48 Biliary disease is the second most frequent cause for urgent non-obstetric surgery during pregnancy.1,4,49,50 Nonetheless, many expectant mothers do not present symptoms secondary to gallstones. This disease is more frequent in pregnant women than in non-pregnant women. The incidence in this subgroup is 0.05%–0.8%.4

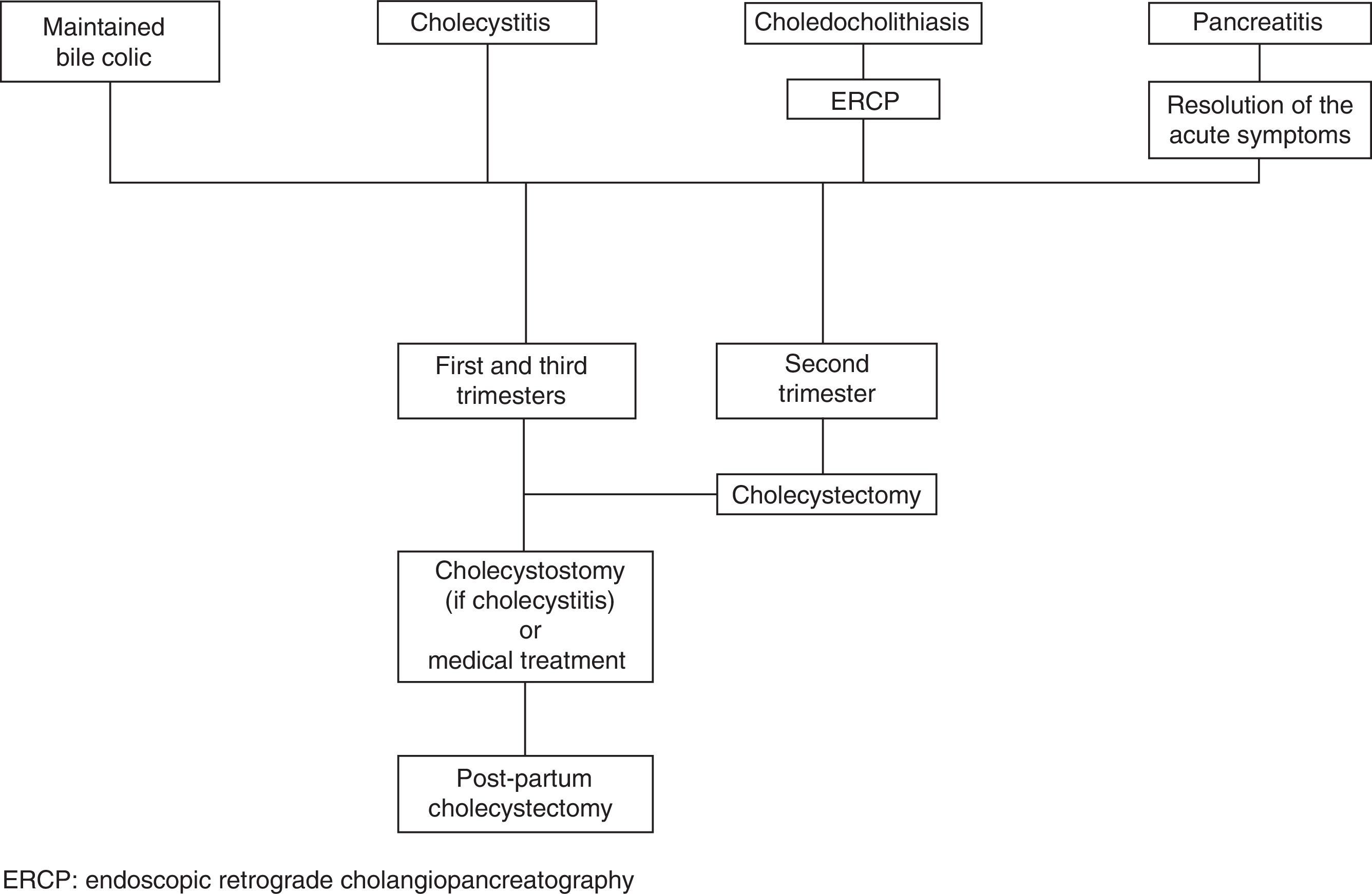

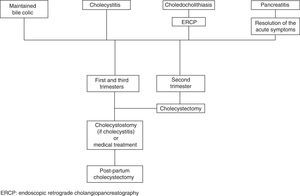

The clinical symptoms that are most frequently observed are maintained biliary colic, cholecystitis, lithiasic pancreatitis and choledocholithiasis. These 4 entities are encompassed in the global term of symptomatic biliary disease. In pregnant women affected by this condition, the most frequent cause for surgical indication is maintained biliary colic (37.5%–70% of cases) followed by acute cholecystitis (20%–32%), choledocholithiasis (7%) and, finally, acute biliary pancreatitis (3%).51,52

Maintained Biliary Colic and CholecystitisThe diagnostic imaging method used is abdominal ultrasound, which has a sensitivity of 80%–90% and a specificity of 88%–100% in the detection of morphological changes.2,4,53

For years, the treatment of symptomatic biliary disease in pregnancy involved conservative management and surgery was delayed until after childbirth in order to avoid foetal risks.48 However, several authors in recent years have refuted this therapeutic strategy. Lu et al.54 report a higher incidence of premature labour in patients with recurring biliary disease treated conservatively compared with those who undergo cholecystectomy. There is also an associated greater number of Emergency Room visits and hospitalisations.3,25,55 Furthermore, there is evidence that conservative management involves an important recurrence rate.3,48 The risk for recurrence is related with the trimester when symptoms appear. If the symptoms start in the first trimester of pregnancy, recurrence reaches 92%. In the second and third trimesters, the risk is 64% and 44%, respectively.3,49,50

Moreover, conservative treatment of symptomatic biliary disease increases the risk of the appearance of cholecystitis by 23%3 and biliary pancreatitis by 13%, which was observed to be associated with foetal death in 10%–20% of cases.2

CholedocholithiasisThe frequency of choledocholithiasis requiring treatment during pregnancy is one out of every 1200 pregnant women.2 Although cholangitis and pancreatitis secondary to choledocholithiasis are uncommon, they are conditions that can increase maternal/foetal morbidity and mortality.2,3

The suspected diagnosis is symptom-based, which usually includes jaundice, but the definitive diagnosis must once again involve diagnostic imaging. Although ultrasound usually shows us indirect signs, such as common bile duct dilatation, it is frequent for the lithiasis not to be visualised in the main bile duct. In these cases, MRI should be ordered for a correct and complete study of the biliary tree.

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, we should conduct an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with sphincterotomy. This procedure is safe during gestation, and it diminishes the postpartum recurrence rate of biliary symptoms.3,48,55,56 However, it does have a rate of complications of 7%–16%, mainly pancreatitis after manipulation, pre-term labour and post-sphincterotomy bleeding.56 To date, there are no clinical trials comparing the intraoperative exploration of the bile tract and ERCP followed by cholecystectomy in these patients. The few cases published about intraoperative exploration show good results.

Biliary PancreatitisPancreatitis is usually mild and receptive to conservative treatment, just as in non-pregnant patients. Only in the case of acute or necrotising pancreatitis would emergency surgery be considered. Once the inflammatory symptoms of the pancreatic gland are resolved, we should opt for cholecystectomy.2 As previously stated, conservative management is linked to a high rate of recurrence, and pancreatitis can cause foetal death in 10%–20%2 or even up to 60% according to some authors.3

Treatment of Complicated Biliary DiseaseCurrently, most publications support surgical instead of conservative management for symptomatic biliary disease during pregnancy. However, not all authors concur about which moment is ideal. Although some defend its use at any time,51,57–59 others prefer surgical intervention during the second trimester as it is the safest and most technically feasible.48,52 Meanwhile, others prefer conducting percutaneous cholecystostomy in cases with acute cholecystitis and delaying surgery until after childbirth.3

To date, laparoscopy has repeatedly demonstrated its advantages over open techniques. It can be done during any trimester of pregnancy, it is safe for both the mother and foetus2,3,51,52,57–59 and, although at the end of the third trimester it can be somewhat more difficult, it does not interfere with visualisation of the surgical field.1 The rate of miscarriages and premature labour is lower with laparoscopic cholecystectomy than with laparotomy.3

The therapeutic algorithm for biliary disease in pregnant women is summarised in Fig. 1.

Postoperative Pain ControlSeveral consensus groups have proposed the analgesia scale of the World Health Organisation for the initial pharmacological approach of acute postoperative pain.60

Postsurgical pain is a trigger for uterine activity, and its optimal management is therefore important. Although some physicians have used progesterone as a tocolytic to prevent post-op uterine irritability and the resulting risk of premature labour, the efficacy of this measure has not been demonstrated.61

Non-opioid analgesics are the most extensively used. Specifically, there is a generalised use of paracetamol and metamizole, as they have demonstrated no harmful effects on the foetus or newborn. Non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, such as dexketoprofen or ibuprofen, are also safe, although their use is not recommended after week 32 of gestation because they can cause closure of the ductus arteriosus.62,63

Opioid analgesia can be used in cases with poor pain control in spite of the non-opioid analgesia. Fentanyl, morphine and hydromorphine are safe alternatives. Oral oxycodone is another option. Nonetheless, it seems that their use in the weeks prior to childbirth can lead to neonatal abstinence syndrome.62,63

Recently, locoregional techniques are gaining in popularity (in these cases, either epidural or intradural) versus systemic analgesia because they have fewer reactions with the foetus and present fewer adverse effects for the mother.64

ConclusionAcute abdomen in pregnant patients is challenging for surgeons. It is of vital importance to reach an early, correct diagnosis supported by the complementary tests necessary to be able to make a therapeutic decision for optimal patient management.

Although surgery may have some risk for low birth weight or premature death, the literature supports its use as any delay could involve a much greater risk for loss of the foetus.

Appendicitis and cholecystitis are the first causes of non-obstetric surgical abdomen during pregnancy. In both cases, the laparoscopic technique has been shown to be at least as safe as laparotomy, and it is associated with faster recovery and shorter hospitalisation. The conservative management of biliary disease is associated with high rates of recurrence. Cholecystectomy is unanimously supported in the second trimester. At other times of the pregnancy, it can be as valid as ERCP (for choledocholithiasis) or cholecystostomy (for cholecystitis) and later postpartum cholecystectomy.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Barber-Millet S, Bueno Lledó J, Granero Castro P, Gómez Gavara I, Ballester Pla N, García Domínguez R. Actualización en el manejo del abdomen agudo no obstétrico en la paciente gestante. Cir Esp. 2016;94:257–265.