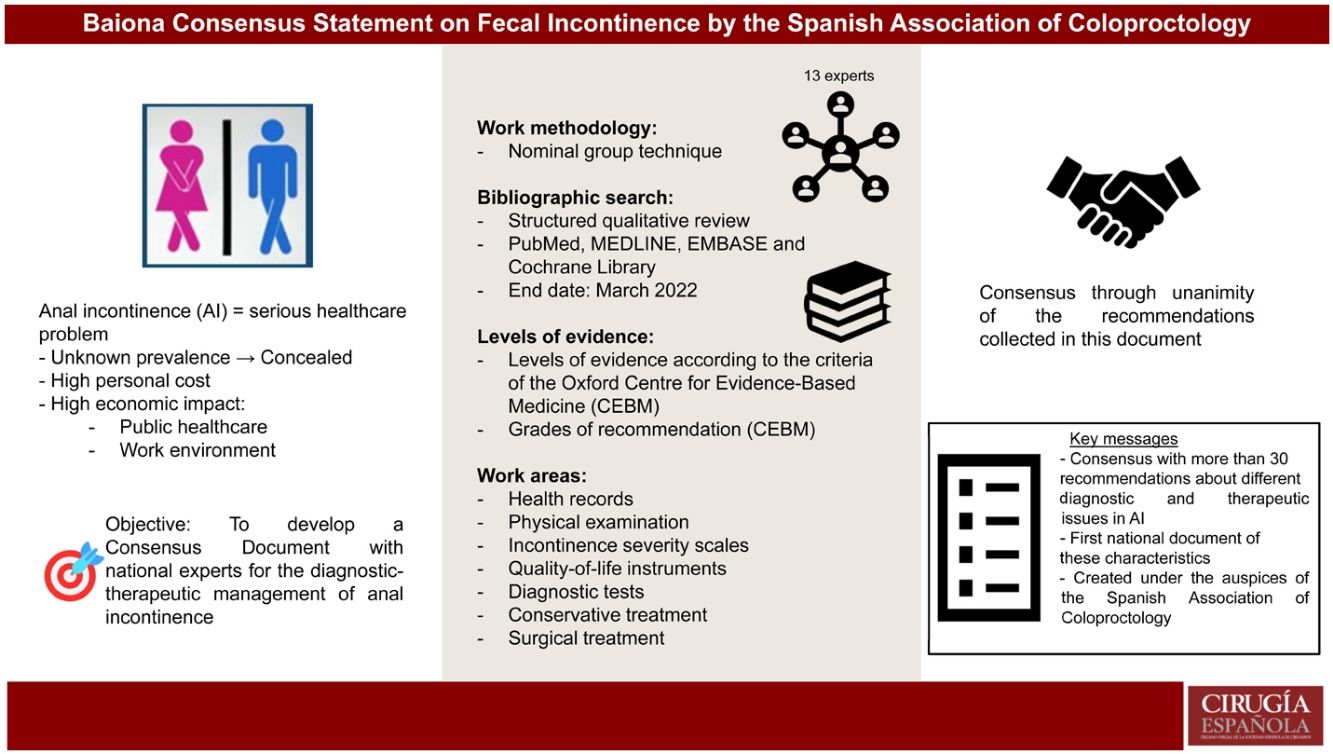

Faecal incontinence (FI) is a major health problem, both for individuals and for health systems. It is obvious that, for all these reasons, there is widespread concern for healing it or, at least, reducing as far as possible its numerous undesirable effects, in addition to the high costs it entails.

There are different criteria for the diagnostic tests to be carried out and the same applies to the most appropriate treatment, among the numerous options that have proliferated in recent years, not always based on rigorous scientific evidence.

For this reason, the Spanish Association of Coloproctology (AECP) proposed to draw up a consensus to serve as a guide for all health professionals interested in the problem, aware, however, that the therapeutic decision must be taken on an individual basis: patient characteristics/experience of the care team.

For its development it was adopted the Nominal Group Technique methodology. The Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation were established according to the criteria of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. In addition, expert recommendations were added briefly to each of the items analysed.

La incontinencia fecal (IF) constituye un importante problema sanitario, tanto a nivel individual como para los diferentes sistemas de salud, lo que origina una preocupación generalizada para su resolución o, al menos, disminuir en lo posible los numerosos efectos indeseables que provoca, al margen del elevado gasto que ocasiona.

Existen diferentes criterios relacionados con las pruebas diagnósticas a realizar, y lo mismo acontece con relación al tratamiento más adecuado, dentro de las numerosas opciones que han proliferado durante los últimos años, no siempre basadas en una rigurosa evidencia científica.

Por dicho motivo, desde la Asociación Española de Coloproctología (AECP) nos propusimos elaborar un Consenso que sirviese de orientación a todos los profesionales sanitarios interesados en el problema, conscientes, no obstante, de que la decisión terapéutica debe tomarse de manera individualizada: características del paciente/experiencia del terapeuta.

Para su elaboración optamos por la técnica de grupo nominal. Los niveles de evidencia y los grados de recomendación se establecieron de acuerdo a los criterios del Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Por otra parte, en cada uno de los ítems analizados se añadieron, de forma breve, recomendaciones de los expertos.

Fecal incontinence (FI) is the loss of the ability to retain or to voluntarily eliminate and discriminate rectal effluents. Factors involved in defecation are neurological, myogenic, sensory, hormonal and anatomical. In addition to these factors are a large number of variables that participate in the complex interaction of continence, such as: stool consistency, reservoir capacity, rectal compliance, rectal sensation, and effective sphincter pressures at rest and during contraction.

The most common etiology (at least in a surgical consultation) is obstetric trauma, although other factors may be involved. The most important include anal surgery, anal and perineal trauma, radiation therapy, chronic straining during defecation, neurological problems, psychosis, side effects of medication, and food intolerance.

Apart from the FI itself, 3 transcendental concepts should be differentiated:

- a)

Passive incontinence: incontinence accident of a complete or near-complete abundant stool, which occurs with no prior warning or desire to defecate, typical of neurological disorders and severe pelvic organ prolapse.

- b)

Soiling: emission of a small amount of feces or mucus through the anus that is continuous, occasional, or post-defecatory, which can cause anal and perianal margin irritation.

- c)

Fecal urgency: sudden desire to defecate which the patient is unable to defer.

The exact incidence and prevalence of FI is difficult to determine, ranging from 2% to 20.7%. This incidence increases in patients admitted to nursing homes and is very frequently associated with urinary incontinence.1,2 It not only has a transcendental psychosocial impact, but it also entails a high financial cost for healthcare systems and individuals.3,4

The diagnosis and treatment of FI are complicated by its multifactorial etiology and multiple conditions involved. Currently, there is no unanimity when it comes to recommending the most effective diagnostic methods or applying the most appropriate therapeutic measures for each case, which is why discrepancies are frequently found in the literature and even among different clinical guidelines.5

MethodsUnder the auspices of the Spanish Association of Coloproctology and during the 27th International Coloproctology Conference held in Baiona (Spain) in 2019, a decision was made to develop a consensus document on fecal incontinence, with the purpose to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of this problematic pathology, directed at all surgeons and healthcare workers concerned about the issue.

Among the different modalities used to develop a consensus document in medicine, the “Nominal Group Technique” was chosen.6,7

The consensus group was comprised of 12 experts, all with extensive experience and interest in FI, and one General Coordinator. A roundtable discussion was held to assess all the problems and discrepancies regarding the diagnosis and treatment of FI.

Six working groups were created with 4 participants each; thus, each expert participated in 2 different groups that analyzed differing topics. A coordinator was nominated for each group, who distributed the topics among the participants. The experts made their evaluations based on their experience as well as an analysis of the literature by means of a structured qualitative review of sources identified by the search engines usually used in biomedical research: PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Library, both in Spanish and English, until March 2022. The search terms were: “anal incontinence”, “fecal incontinence”, “sphincteroplasty”, “sacral nerve stimulation”, “posterior tibial nerve stimulation”, “bulking agents”, “dietary treatment”, and “artificial anal sphincter”.

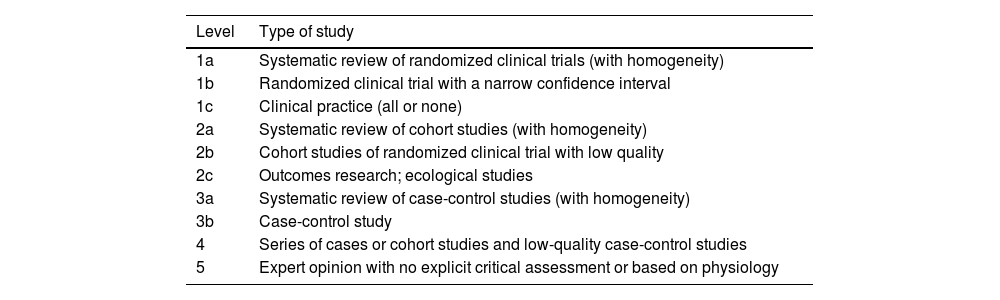

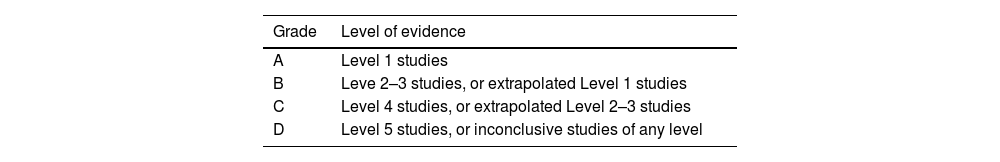

Clinical experimental articles in Spanish and English were included in order to evaluate and present possible future alternatives. The Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation were established following the criteria of the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine8 (Tables 1 and 2).

Levels of evidence according to the criteria of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM).

| Level | Type of study |

|---|---|

| 1a | Systematic review of randomized clinical trials (with homogeneity) |

| 1b | Randomized clinical trial with a narrow confidence interval |

| 1c | Clinical practice (all or none) |

| 2a | Systematic review of cohort studies (with homogeneity) |

| 2b | Cohort studies of randomized clinical trial with low quality |

| 2c | Outcomes research; ecological studies |

| 3a | Systematic review of case-control studies (with homogeneity) |

| 3b | Case-control study |

| 4 | Series of cases or cohort studies and low-quality case-control studies |

| 5 | Expert opinion with no explicit critical assessment or based on physiology |

Once the corresponding items were prepared by each expert, they were assessed by the Group Coordinator and the General Coordinator, who included comments that they considered appropriate. After this second proposal, the topics were sent to all the members of the group for another assessment. After the final analysis in each Group, the study and proposals were sent electronically to the entire group of experts who again made the recommendations they deemed pertinent.

Lastly, the manuscript and its main recommendations were presented at the 28th International Coloproctology Conference, held in Baiona in 2022.

After this rigorous preparation, the Baiona Consensus Statement on Fecal Incontinence document was drawn up, under the auspices of the AECP.

Clinical history — physical examinationConsidering the possible multifactorial etiology, all antecedents that could alter one or more should be analyzed in the clinical history. The medical history must include the following factors:

Symptoms of incontinence- •

Time of evolution

- •

Correlation with changes in intestinal habit

- •

Characteristics of incontinence (soiling, passive, defecatory urgency, mixed)

- •

Intensity of symptoms (severity of incontinence)

- •

Accompanying symptoms (mucorrhea, bleeding)

- •

Finally, questions aimed at clarifying the type of involvement, defining the following factors:

- o

QUALITY: lack of control refers to gases, liquid stools or solid stools?

- o

FREQUENCY: leaks are daily, weekly, monthly, or sporadic?

- o

DEGREE OF SOCIAL IMPACT: exact impact for each person?

- o

All of these parameters are quantified using a calendar or evacuation diary that patients complete for three weeks, where all events related to incontinence are recorded in detail.9–11

Background — identification of risk factors- •

Age

- •

Hygienic-dietary habits (tobacco, amount of fiber in the diet, body mass index, limited physical activity)

- •

Medical history (neurodegenerative, metabolic, digestive pathology)

- •

Previous medication, or changes

- •

Associated urinary incontinence

- •

Surgical history (previous anorectal surgery)

- •

Obstetric–gynecological history (childbirth, laborious births, traumatic births, hysterectomy, genital prolapse)

- •

Trauma history (pelvic–perineal trauma)9,11–13

A detailed physical examination is essential for the correct evaluation of patients with FI, which will include:

Inspection of the perineal area (rest and contraction) to evaluate scars, asymmetries, suppurative pathology, prolapses, perineal descent and dermatitis or excoriations in the perianal skin, as well as sensitivity in the perineal skin.

The digital rectal examination provides subjective, but very reliable, evaluation of rest and effort pressures as well as muscle coordination, with expulsion or retention maneuvers. Furthermore, it rules out pathologies, such as rectal tumors or stenosis and sometimes the presence of fecal impaction.14

Basic instrumentation (anoscopy, proctoscopy) can be useful as a complement to rectal examination to identify other anal pathologies.3,15

Expert recommendations

To study fecal incontinence, a detailed and directed anamnesis is essential, as well as a physical examination that includes inspection and examination, both digital and instrumental.

Level of evidence 1c; grade of recommendation A.

Scoring instruments that evaluate the severity of fecal incontinenceMeasuring FI is challenging. To evaluate the severity of this symptom, several scoring systems have been developed to define the subjective perception of the patient, evaluate the treatments for their scientific dissemination in a homogeneous manner.

Scoring instruments can be either simple scales or grading scales. On simple scales, patients define their degree of fecal continence ranging from 0 to 10.

Grading scales include measuring fecal loss in type and frequency, the use of coping mechanisms, and the impact on lifestyle.

In our setting, the most used scales are the Cleveland Clinic or Jorge–Wexner scores16 and the St Mark’s or Vaizey incontinence scales,17 which are easy to conduct and interpret.

None of these scales have been validated, nor do they assess soiling. This has led certain studies to analyze the limited correlation between the assessment of the scores and the subjective perception reflected by the visual analogue scale.18

In the literature, there is no consensus on which is the best instrument to assess the severity of fecal incontinence, but these should be used to identify more severe symptoms that may initially require more aggressive treatment. By homogenizing the treatments established, results could be compared between studies, populations and institutions.

Scoring instruments to evaluate the quality of life in fecal incontinenceThe impact of fecal incontinence on quality of life is a vital point in the management of these patients. Quality-of-life assessment scales are divided into generic and specific types. The most widely used generic scale is the SF-36 (Medical Outcomes Survey Short-Form),19 and the most widespread specific instrument (validated in Spanish) is the FIQL scale (Fecal Incontinence Quality-of-Life Scale).20

Expert recommendation

In the medical assessment of fecal incontinence and for scientific research purposes, specific severity and quality-of-life scales should be used in these patients, even though there are no studies that support their routine use.

Level of evidence 5; grade of recommendation D.

Diagnostic tests in fecal incontinenceEndoanal ultrasoundThis is the main test used to study fecal incontinence, since objective, higher-quality images of the anal sphincters can be obtained compared to other methods. In most studies, its sensitivity and specificity for the detection of sphincter defects are in the range of 83%–100%.21,22

3D ultrasound does not provide much more information than 2D.23 The Starck score can be useful in the evaluation of these patients, especially in the presence of obstetric damage.24

Transvaginal and transperineal ultrasoundThese can be useful in the event that the endoanal probe cannot be used.25

Magnetic resonance imagingEspecially useful to detect external anal sphincter (EAS) atrophy26,27

Defecography and MRI defecographyIts use must be individualized and used on an exceptional basis.28

Anal manometry and sensitivity testsConventional anal manometry, with electronic or pneumatic perfusion, is used to measure anal canal pressures and rectal sensitivity. As a minimum, the following parameters must be collected: maximum resting pressure, maximum contraction pressure, length of the anal canal (at rest and contraction), point of maximum pressure, minimum and maximum tolerated sensitivity, and finally the rectoanal inhibitory reflex.29,30

Neurophysiological testsThese are not frequently recommended.

In the future, we must consider the role that the determination of evoked potentials will play in testing the cerebral cortex. Likewise, the determination of the conduction of peripheral nerves, especially the posterior tibial nerve (in its sural sensory and motor branches) should be considered to assess therapy with peripheral neurostimulation.31,32

Anoscopy and rectoscopyThese are used in order to rule out other coexisting processes, especially in patients with tenesmus.33 In select cases, colonoscopy is used.

Expert recommendations

1) Anal ultrasound is mandatory in the diagnosis of patients with fecal incontinence, especially to detect structural anomalies of the sphincter complex.

Level of evidence 3b; grade of recommendation B.

2) MRI can be useful in certain circumstances, especially to determine sphincter atrophy.

Level of evidence 3b; grade of recommendation C.

3) Both defecography and MRI defecography have limited value in the diagnosis of FI, as they only have a certain role in patients presenting prolapses of other pelvic organs.

Level of evidence 3b; grade of recommendation C.

4) Colonoscopy can be useful for diseases that may exacerbate FI (diarrhea, etc.), but the related data available are very limited.

Level of evidence 5; grade of recommendation D.

5) Anorectal manometry can be useful in the diagnosis of FI, but never alone.

Level of evidence 3b; grade of recommendation C.

6) Although manometry can be useful to guide treatment alternatives, it is currently difficult to know its true impact.

Level of evidence 3b; grade of recommendation B.

7) High-resolution manometry is a new and promising technique; however, there are currently not enough studies to support its recommendation.

Level of evidence 4; grade of recommendation C.

8) Latency of the Motor Nerve should not be used in the diagnosis of fecal incontinence as a predictor of a successful sphincteroplasty.

Level of evidence 4; grade of recommendation C.

9) Needle electromyography (EMG) is the only technique to identify neurological damage.

Level of evidence 2a; grade of recommendation B.

Conservative treatmentDifferent conservative measures can provide satisfactory results that avoid surgical treatment. These include:

DietDietary modifications can provide satisfactory results, with the aim of improving the frequency and consistency of bowel movements.34,35

Expert recommendations

In patients with fecal incontinence, it is advisable to record daily eating habits in a diary in order to personalize dietary recommendations.

Level of evidence 3b. Grade of recommendation C.

FiberFiber improves stool consistency by absorbing excess intraluminal water. It is indicated in cases of fecal incontinence associated with diarrhea and liquid stools or stools of reduced consistency.36,37

Expert recommendations

Psyllium may be indicated in patients with fecal incontinence associated with stools of a soft or liquid consistency. Said fiber must be administered with a small amount of water so that the astringent effect is achieved.

Level of evidence 3b; grade of recommendation C

Transanal irrigationThis is based on emptying the colon of the maximum amount of fecal matter, used regularly. The published results are variable, the dropout rate is high, and adverse effects are not negligible.38,39 However, it can be recommended in select cases.40

Expert recommendations

Transanal irrigation may be recommended as a second line of treatment in patients with defecatory dysfunction of neurological causes or with low anterior resection syndrome.

Level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B.

Pharmacological treatmentDifferent drugs have been used with the aim of achieving pseudo-constipation to avoid soft or liquid stools, or with the purpose of increasing the resting pressure of the internal sphincter.41–44 The evidence is very limited, with multiple biases, which has led to its use being exceptional.

Expert recommendations

Antidiarrheal drugs like loperamide may be indicated in patients with fecal incontinence associated with stools of a soft or liquid consistency.

Level of evidence 2a; grade of recommendation B.

Experience is limited with the use of topical drugs that increase anal pressure or with the administration of antidepressants.

Level of evidence 4; grade of recommendation D.

BiofeedbackThe objective of biofeedback is to strengthen the pelvic muscles, re-educate rectal sensitivity and coordinate the pelvic muscles with defecation.45–47 In addition, it can be a satisfactory complementary treatment after sphincteroplasty.48,49

Expert recommendations

Biofeedback may be useful in the treatment of FI in combination with other conservative treatment modalities.

Level of evidence 2a; grade of recommendation B.

Pelvic floor rehabilitationThis entails performing short or long repeated contractions of the external anal sphincter and the puborectalis, while keeping the abdominal muscles relaxed. Better results have been reported when it is used in combination with biofeedback.50,51

Expert recommendations

Pelvic floor rehabilitation is a treatment option for fecal incontinence as part of conservative treatment, which is recommended based on its low cost, low morbidity and some evidence of effectiveness. Patients with little or no sphincter contractility capacity should be excluded. Its use is recommended in association with biofeedback.

Level of evidence 3b, grade of recommendation B.

ElectrostimulationElectrostimulation consists of the utilization of anal probes or electrodes placed in the perineum. There is no evidence on possible benefits.52–54

Expert recommendations

Although there is little evidence, it seems that electrostimulation at high frequencies can improve the effectiveness of biofeedback.

Level of evidence 4; grade of recommendation D.

Palliative measuresAnovaginal mechanical devicesThese are passive obstruction barriers that block the flow of feces in the rectum to help prevent fecal incontinence. Data on their effectiveness are limited.55–59

Expert recommendations

There is no evidence to indicate the use of anal plugs in fecal incontinence, although they may be recommended in select patients, with warnings about possible intolerance.

Level of evidence 4; grade of recommendation D.

The evidence for the use of mechanical vaginal devices for the treatment of fecal incontinence is limited, but they may be a good alternative within conservative treatments.

Level of evidence 4. Degree of recommendation D.

Surgical treatmentSphincteroplasty. Other surgical optionsIndicationsExternal anal sphincter (EAS) repair is indicated in patients with symptoms of fecal incontinence, with a limited defect and sufficient residual muscle mass. Its objective is to restore the anatomical barrier necessary for continence. It can be indicated for any type of EAS lesion, but the patient selection criteria and results obtained are extremely variable.42,60–70

Surgical techniqueSphincteroplasty or suture of the external anal sphincter (EAS)Sphincteroplasty is the most commonly performed technique to treat EAS defects secondary to obstetric, postoperative or accidental trauma.63,71–75

There is a growing tendency to use overlapping, even in primary repairs, although there are several technical variations depending on the habits and experience of each surgeon, with variable results.75–77

Expert recommendations

Sphincteroplasty is indicated in patients with severe fecal incontinence and observed sphincter injury of EAS or both sphincters between 30º and 180º of separation and that does not respond to conservative measures.

Level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B.

Overlapping the sphincter ends is superior to direct repair.

Level of evidence 3b; grade of recommendation B.

There are no differences between the use of resorbable suture material in the medium or long term.

Level of evidence 1b; grade of recommendation A.

Repair of both sphinctersThere is enormous technical variability in relation to en bloc suturing of both sphincters or with individualized repair, and different series have reported non-homogeneous results.63,72,76–80 However, other authors have published satisfactory results with selective IAS suture, separated from the EAS.64,74,75 Given the variability of lesions in each case, rigorous randomization seems extremely difficult.

Expert recommendations

- -

Individualized repair of both sphincters improves results, so it should be performed whenever possible.

Level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B.

Isolated internal anal sphincter (IAS) repairThis has been attempted for defects with very symptomatic passive leaks secondary to fistulotomy or internal sphincterotomy. Although the results are usually not satisfactory, they can provide significant improvement to well-selected patients.81–83

Expert recommendations

- -

Repair of isolated IAS lesions can be performed, although with a low level of evidence.

Level of evidence 4; grade of recommendation C.

Association with levator plicationThis has been used in association with sphincteroplasty, not only to treat sphincter defects,75,84 but also when there are none.85 However, there is no clear evidence of its use in cases of obstetric injuries, and it can lead to dyspareunia if the suture is tense.

Expert recommendations

- -

Levatorplasty should not be systematically associated with sphincteroplasty in obstetric injuries.

Level of evidence 5; grade of recommendation D.

Association with plastic surgeryIn patients with a thin or absent perineal body, or even with a common anovaginal cloaca, plastic surgery procedures have been performed with good results, both in terms of improving continence and sexual function.86–88

Re-sphincteroplastyWhen an anterior muscle defect persists or occurs over time, most series have obtained good results with re-sphincteroplasty. The failure of an initial repair does not exclude a new one.89–91

Expert recommendations

- -

It is feasible to perform a new sphincteroplasty when persistence or recurrence of the sphincter defect is proven.

Level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B.

Complications and preventionComplications associated with sphincter repair occur in 15% of cases; they are usually mild and include infection and dehiscence of the surgical wound, abscess, bleeding, urinary retention, fecal impaction, dehiscence of the sphincter suture, pain and dyspareunia.92,93 Preventive measures are based on empirical treatments and general recommendations, such as the use of prophylactic antibiotics, partial or non-closure of the surgical wound, the use of antegrade colon preparation or preoperative cleansing enemas, and bladder catheterization, with no evidence of any benefits.

Protective stomas have been described in situations of risk of perianal sepsis and in extensive or complex sphincter defects, but they do not provide any benefit over a regular sphincteroplasty,94 nor does “chemical colostomy” seem to offer significant advantages.92

Expert recommendations

- -

A protective stoma is unnecessary to prevent complications after performing a sphincteroplasty.

Level of evidence 1b; grade of recommendation A.

ResultsSphincteroplasty improves fecal incontinence in 70%–90% of cases in the short term, but the assessment of success differs according to the studies,72,73,95 and they generally deteriorate over time.

However, other studies with long-term follow-up and rigorous controls demonstrate sustained improvement, confirming the prolonged effectiveness of the technique.61,66,75,96 Even so, patients should be informed about the possibility of progressive deterioration of sphincter function over time. No significant factors have been described for a poor prognosis.97

Expert recommendations

- -

Despite possible deterioration over time, sphincteroplasty provides functional results and improvement in quality of life that are satisfactory enough to be recommended.

Level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation C.

Pelvic floor repairIndicationsIndications include idiopathic (neuropathic) fecal incontinence and complex trauma to the external anal sphincter and puborectalis muscle.98,99 It has also been used in patients with descending perineum syndrome associated with decreased anal canal pressure and altered anorectal angle.100 Currently, it is an uncommon procedure.101,102

Expert recommendation

Pelvic floor repair can be performed in selected patients with idiopathic fecal incontinence and descending perineum syndrome, in whom significant weakness of the sphincter complex is observed, when other therapeutic options are not possible.

Level of evidence 4; grade of recommendation C.

Use of other muscles: muscle transpositionThe objective is to create a neo-anal sphincter when direct repair of the sphincter complex is considered inappropriate, with the aim of passively increasing output resistance in patients with severe symptoms.

The most commonly used procedure is dynamic graciloplasty. The results are very heterogeneous, and the complication rate is high.103–107 The use of gluteoplasty is currently unusual.108,109

Expert recommendations

Graciloplasty and gluteoplasty, performed at medical centers with experience, can be considered in motivated patients as a final alternative prior to a colostomy.

Level of evidence 4; grade of recommendation D.

Sacral neuromodulationWhat is it?Sacral neuromodulation (SNM) involves electrically stimulating a root of the sacral spinal nerve to modulate a neural pathway with the aim of treating defecatory dysfunction. After a test phase, if satisfactory, we move on to chronic or definitive stimulation. The surgical technique is highly reproducible and should be performed according to standards described by several expert committees.110–115

The mechanism of action of SNM is not yet completely known, but it is believed to act at the somatic motor, somatosensory, and autonomic levels, while mediating somatovisceral reflexes. It is seemingly not limited to the effector organ, as central and cortical effects have been demonstrated.116,117

Expert recommendations

A thorough and multangular evaluation of patients is necessary (defecation diary, subjective evaluation, scores, etc.), both at baseline and during the test phase, to avoid false positives or false negatives. The recommended cut-off point is 50% improvement in the evaluated parameters, although individualization is important.

Level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B.

IndicationsIn general terms, SNM is considered the second line of treatment for patients with moderate or severe FI who have not found improvement through conservative treatment.118–122 The short-term results in the literature demonstrate a reduction of more than 50% in incontinence episodes in 79% of patients implanted, maintaining an effectiveness of 83% after 3 years of follow-up.121,123–126

Expert recommendations

Sacral neuromodulation can be indicated as a second line of therapy in patients with fecal incontinence in whom conservative treatment fails. Multifactorial FI best responds to SNM.

Level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B.

MorbidityThe morbidity of SNM is low and mild, including pain related to stimulation or the implanted device and infection of the system. Patient followed-up should be lifelong because the incidence of minor events or transient relapses is considerable.127

Expert recommendations

It is recommended to closely monitor immune status and coagulation prior to performing SNM.

Level of evidence 3b. Grade of recommendation C.

There is no consistent evidence on how to act on the stimulation parameters when confronted with different incidents during follow-up, so it is recommended to rely on clinical experience.

Level of evidence 4; grade of recommendation D.

Efficacy by etiopathogenic subgroupsFecal incontinence in patients with injury to the external anal sphincterThe presence of a sphincter injury does not seem to influence the result of SNM.118,128,129

Expert recommendations

Neuromodulation may be indicated in selected patients with sphincter injury, preferably of long duration.

Level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B.

Neurological fecal incontinenceThere is little evidence on its effects on neurological fecal incontinence.130,131

Expert recommendations

SNM offers a promising therapeutic option for patients with neurogenic incontinence refractory to other therapies.

Level of evidence 4; grade of recommendation C.

Incontinence in low anterior resection syndrome (LARS)Although applied in small, heterogeneous samples, the results are encouraging.132–134

Expert recommendations

Although it is necessary to agree on a correct algorithm that considers the different variables related to LARS, SNM is indicated in these patients when conservative treatment has failed.

Level of evidence 4; grade of recommendation C.

Fecal incontinence in the context of chronic diarrheaVarious studies have shown improvement in the number of bowel movements after neuromodulation applied in different diarrheal conditions, although the evidence is scarce.135

Expert recommendations

Given the persistence of incontinence associated with diarrhea despite the application of conservative treatments, and after assessment by a digestive specialist, a neuromodulation trial phase may be indicated.

Level of evidence 4; grade of recommendation C.

Congenital fecal incontinenceThere is little experience, and complex cases require thorough study and strict individualized technique.136–138

Expert recommendations

After meticulous study to confirm the existence of residual sphincter apparatus, SNM can be attempted in this type of patient.

Level of evidence 4; grade of recommendation C.

Posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS)The posterior tibial nerve contains sensory, motor, and autonomic fibers that originate from the roots of the S2–S4 sacral plexus. Its stimulation affects the sacral roots in retrograde related to visceral and muscular control of the pelvic floor, but the exact mechanism of action is unknown.139

Treatment can be percutaneous, with needle electrodes, or transcutaneous, with surface electrodes.140–142 Bilateral stimulation has been tested in limited studies.143,144

There are still numerous unknowns regarding indications, differences with SNM, need to maintain treatment, stimulation regimens and long-term results.145–151

Expert recommendations

1) PTNS offers an alternative to patients with less severe fecal incontinence, although its results are sometimes discreet.

Level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B.

2) The short- and medium-term results and its high acceptance by patients mean that PTNS can be used as a bridge therapy before offering SNS.

Level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B.

3) It can be performed both percutaneously and transcutaneously.

Level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B.

4) A standardized administration schedule cannot be recommended, although it seems that the most frequently used is 1–2 sessions per week for 3 months, followed by “booster” treatments with no clear schedule.

Level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B.

5) Offering PTNS when conservative treatment and/or biofeedback fail can reduce the need for SNS, or at least delay it.

Level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B.

Less common proceduresArtificial anal sphincter (AAS)The high number of complications, with no viable solutions, has led to the disappearance of AAS.152–154

Magnetic anal sphincter (MAS)The complication rate is high, and it has been taken of the market.

Bulking agentsThe use of these products presents low complexity and morbidity rates.78,155,156 They are indicated in cases of internal sphincter injuries that cause soiling.78 There are no long-term results available.155–158

Expert recommendations

The use of bulking agents is a valid option for patients with soiling or other effects derived from an injury to the internal sphincter.

Level of evidence 3b; grade of recommendation C.

Injection of mesenchymal cellsThis application is used in experimental research.159–161

Expert recommendations

Cell therapy presents promising results, but it is currently in the experimental field, so there is no evidence for its recommendation.

Radio frequency (SECCA)Favorable results are limited, so its use is currently very limited.162–164

Expert recommendations

Although there is evidence of clinical improvement, poor long-term results mean that its use is currently very limited.

Level of evidence 3b; grade of recommendation C.

TOPAS (Trans Obturator Posterior Anal Sling)Preliminary results are favorable,165–167 but its use is not approved.

Expert recommendations

Product not approved despite good preliminary results.

Malone anterograde continence enema (MACE)Possible option in very select cases, but not free of complications.168–170

Expert recommendations

Malone anterograde continence enema is a valid therapeutic option in patients with incontinence and constipation, or with neurogenic bowel dysfunction, prior to the indication of a colostomy.

Level of evidence 3b; grade of recommendation C.

AcupunctureFew studies, but good results171,172

Expert recommendations

In the absence of evidence, it cannot be recommended as a treatment.

Pyloric valve transpositionAnastomosis between the distal colon and the perianal skin, and the pylorus acts as a valve or “sphincter” mechanism.173–175

Expert recommendations

In the absence of clinical evidence, this alternative is in the experimental phase.

ColostomyAlthough it is an aggressive option, it can radically improve the quality of life of patients when all therapeutic options have failed.176

Expert recommendations

No comparative studies have been published. Its use is recommended in consensus with the patient as the last therapeutic option.

In conclusion, FI is an important problem that significantly affects the quality of life of patients. There are numerous therapeutic options, which must be established only after thorough, meticulous assessment on an individualized basis.

FundingThe authors declare that they have received no funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors of the article do not have any commercial association that might pose a conflict of interest in relation to this article.