The prognosis for pancreatic adenocarcinoma has changed very little in recent decades and still continues to be dismal. It has been demonstrated that surgical resection is the only therapeutic option that is able to achieve greater long-term survival (18% 5-years post-pancreaticoduodenectomy [PD], and only 12% when there are metastases in the regional lymph nodes).1–3 Using these data, pancreatic resection is traditionally considered contraindicated when there are synchronous liver metastases at the time of surgery.

We present a case of long-term survival after PD with simultaneous resection of synchronous liver metastases and deferred surgery for multiple metachronous liver metastases.

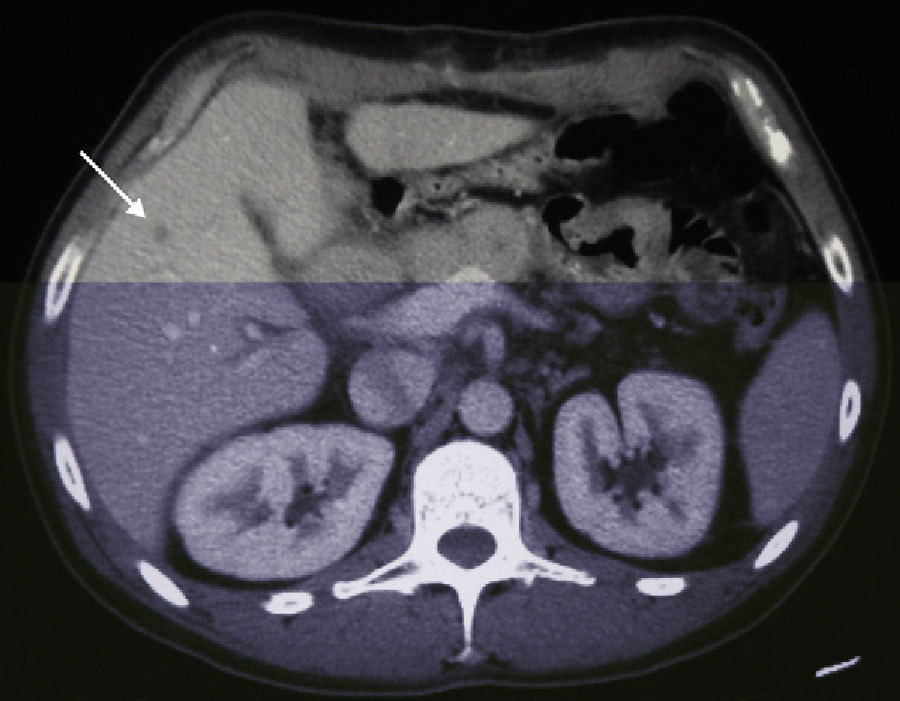

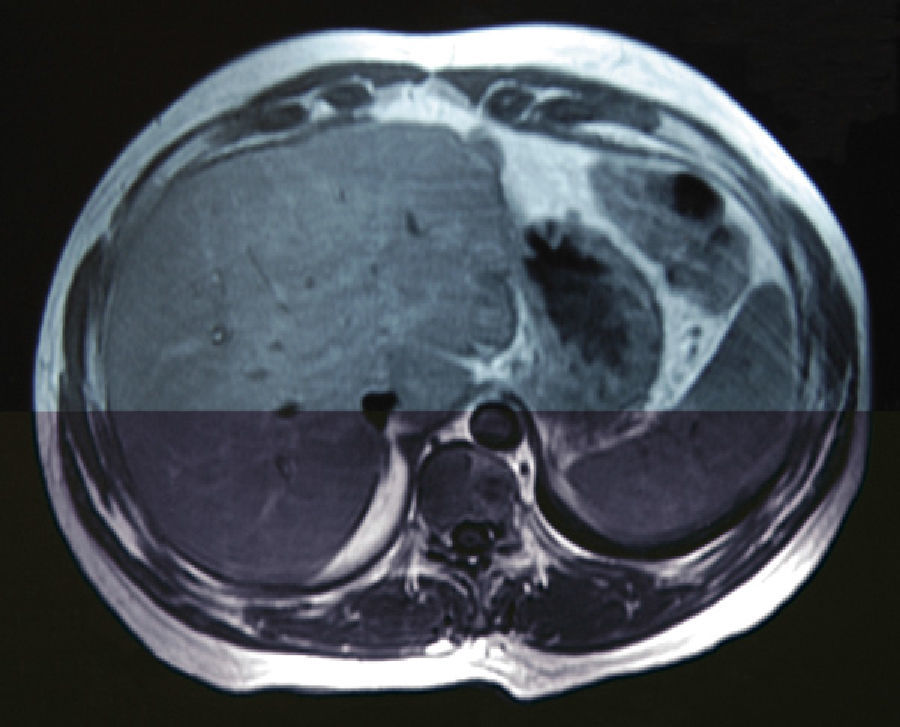

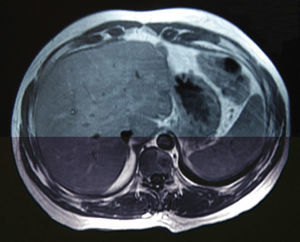

A 38-year-old male with no prior medical history came to our emergency department in December 2006 with weight loss, jaundice and abdominal pain in the upper right abdominal quadrant. Computed tomography (CT) detected a space-occupying lesion measuring 15mm×9mm at the head of the pancreas, with no suspicion of extra-pancreatic disease. A malignant lesion was suspected, and a PD was proposed. During the surgery, a solitary superficial lesion in the liver was biopsied. As the intraoperative histopathologic study ruled out malignancy, we proceeded with the standard Whipple procedure. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the definitive pathology analysis reported ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas measuring 25mm with moderate differentiation (pT2), and absence of pathologic lymph nodes (pN0). The differed study of the biopsied liver nodule revealed the presence of pancreatic metastatic tumor cells. In a follow-up control in June 2007, 7 hepatic metastases were detected in segments ii (×1), iii (×3), iv (×1), v (×1) and viii (×1) (Fig. 1), and chemotherapy was therefore initiated with gemcitabine and capecitabine as palliative treatment. The patient presented good response to the protocol, with partial regression of the hepatic metastases and persistence of only 2 lesions in a CT done in November 2008. Given this situation, we re-considered the therapeutic strategy, and rescue surgery was proposed. During laparotomy, 6 subcentimeter metastases (segments ii, iii, iv, v, viii) were identified and resected. In addition, a larger lesion was detected in the ivb-v segment, which was treated by means of radiofrequency ablation. The pathology study demonstrated the presence of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in all the resected lesions. The patient remained disease-free for 50 months after the pancreatic resection, 28 months after the second hepatic surgery (Fig. 2). In April 2011, a follow-up CT detected multiple bilateral subcentimeter liver metastases. Since then, the patient has been treated with a 15-day regimen of gemcitabine and cisplatin that maintains the disease stable.

The current situation of hepatic resection due to colorectal or neuroendocrine metastases is well defined. In contrast, the effectiveness of hepatic surgery for liver metastases whose primary origin is that of different locations or different histologic origins is controversial. In spite of the fact that hepatic resection due to metastases of non-colorectal or neuroendocrine origin is gaining popularity and the number of patients who are being resected is increasing,4 few studies support surgery for liver metastasis of pancreatic cancer. Based on recently published data, the observed overall survival ranges between 5.9 and 8.3 months after the resection of synchronous metastases and 5.8 to 20 months for the resection of metachronous metastases.2,5 Meanwhile, chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer has undergone few changes since the approval of gemcitabine.6 Only 2 combinations (erlotinib+gemcitabine and gemcitabine+capecitabine) have been shown to increase survival, despite the many trials done with gemcitabine and other chemotherapy drugs.7–9 The choice of one or the other drug combination is mainly based on the balance between toxicity and benefit. In our case, age and the absence of comorbidities enabled us to select a combination of gemcitabine and capecitabine, which was able to stabilize the metastatic disease and significantly improve survival.

Some centers recommend PD as a palliative procedure because tumor reduction may improve the patients’ quality of life.3 Nevertheless, most studies report similar survival rates in patients who undergo PD with positive microscopic margins (R1) compared with those who received non-surgical treatment.10 Moreover, the extension to the liver may represent systemic disease, which is incurable with surgery, in addition to being a procedure with very high rates of morbidity; thus, most surgeons agree that it presents little benefit. In spite of this, our case demonstrates that sometimes a prolonged survival is possible (current survival is 58 months after the first surgery, 38 months after resection of metachronous liver metastases). We agree that surgery cannot be the rule in these cases, but a strategy that combines chemotherapy and surgery may be successfully used in selected cases. Although we cannot talk about a cure in the context of metastatic pancreatic cancer, it should be kept in mind that an aggressive surgical approach may offer a young patient with little comorbidity the opportunity of a prolonged survival, especially if the metastatic disease stabilizes after chemotherapy.

Please cite this article as: Lorente-Herce JM, Parra-Membrives P, Díaz-Gómez D, Martínez-Baena D, Márquez-Muñoz M, Jiménez-Vega FJ. Supervivencia prolongada tras resección de metástasis hepáticas de adenocarcinoma de páncreas. Cir Esp. 2013;91:390–392.