Intramural duodenal hematoma is a rare entity, and current scientific evidence is based on reports of isolated cases. The highest incidence is observed in patients under 30 years of age, as most are secondary to blunt abdominal trauma (70%–80%).1 The second most frequent age group is the elderly, caused by spontaneous duodenal hematomas associated with oral anticoagulants, often due to overdosage. Other less frequent causes include: severe pancreatitis (which, in the inflammatory context, can erode the pancreaticoduodenal vessels), duodenal ulcer (as a consequence of endoscopic procedures), primary coagulopathies and thrombocytopathies (usually in the context of malignant hematological diseases or due to the adverse effect of chemotherapy drugs).2

We present a series of 7 cases of duodenal intramural hematoma, including 3 men and 4 women, from the period between January 2010 and February 2022. Demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1, together with other series published to date with more than 4 cases. None of the patients were being treated with NSAID or antiplatelet drugs, nor did they have baseline coagulopathy. Table 2 describes the causes of duodenal hematoma, treatment and postoperative complications for our series. No serious postoperative complications were recorded. Three patients required intensive care, with a mean stay of 5.6 ± 2 days. Total resolution of the hematoma was obtained in a mean of 26 ± 14 days. There were no recurrences of the hematoma or mortality in the first 90 days. The patient with the pancreatic neoplasm died 9 months later due to progression of this oncological disease. Two other patients died of causes unrelated to the duodenal hematoma: one after 86 months, and the other after 13 months.

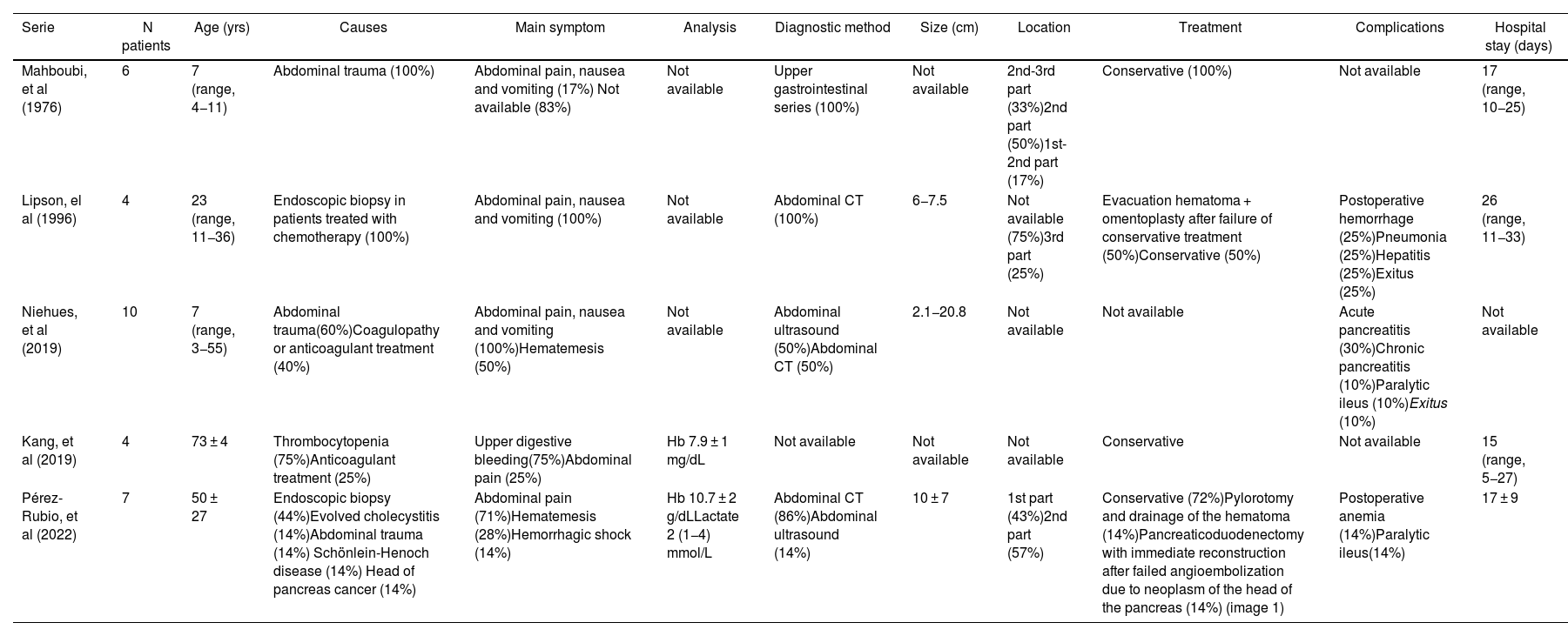

Description of the series of cases hematoma intramural duodenal that include 4 or more patients.

| Serie | N patients | Age (yrs) | Causes | Main symptom | Analysis | Diagnostic method | Size (cm) | Location | Treatment | Complications | Hospital stay (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mahboubi, et al (1976) | 6 | 7 (range, 4−11) | Abdominal trauma (100%) | Abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting (17%) Not available (83%) | Not available | Upper gastrointestinal series (100%) | Not available | 2nd-3rd part (33%)2nd part (50%)1st-2nd part (17%) | Conservative (100%) | Not available | 17 (range, 10−25) |

| Lipson, el al (1996) | 4 | 23 (range, 11−36) | Endoscopic biopsy in patients treated with chemotherapy (100%) | Abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting (100%) | Not available | Abdominal CT (100%) | 6−7.5 | Not available (75%)3rd part (25%) | Evacuation hematoma + omentoplasty after failure of conservative treatment (50%)Conservative (50%) | Postoperative hemorrhage (25%)Pneumonia (25%)Hepatitis (25%)Exitus (25%) | 26 (range, 11−33) |

| Niehues, et al (2019) | 10 | 7 (range, 3−55) | Abdominal trauma(60%)Coagulopathy or anticoagulant treatment (40%) | Abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting (100%)Hematemesis (50%) | Not available | Abdominal ultrasound (50%)Abdominal CT (50%) | 2.1−20.8 | Not available | Not available | Acute pancreatitis (30%)Chronic pancreatitis (10%)Paralytic ileus (10%)Exitus (10%) | Not available |

| Kang, et al (2019) | 4 | 73 ± 4 | Thrombocytopenia (75%)Anticoagulant treatment (25%) | Upper digestive bleeding(75%)Abdominal pain (25%) | Hb 7.9 ± 1 mg/dL | Not available | Not available | Not available | Conservative | Not available | 15 (range, 5−27) |

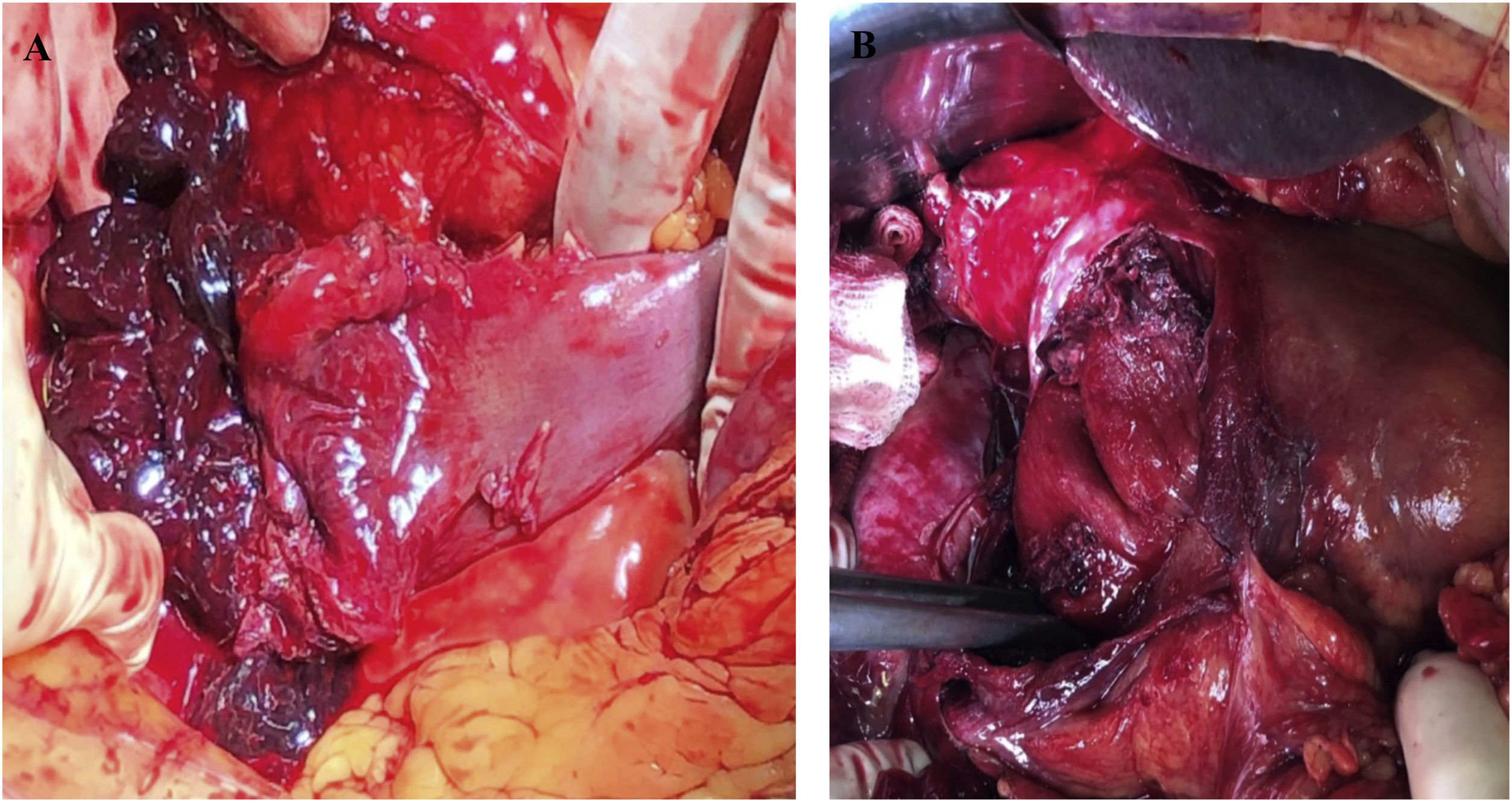

| Pérez-Rubio, et al (2022) | 7 | 50 ± 27 | Endoscopic biopsy (44%)Evolved cholecystitis (14%)Abdominal trauma (14%) Schönlein-Henoch disease (14%) Head of pancreas cancer (14%) | Abdominal pain (71%)Hematemesis (28%)Hemorrhagic shock (14%) | Hb 10.7 ± 2 g/dLLactate 2 (1−4) mmol/L | Abdominal CT (86%)Abdominal ultrasound (14%) | 10 ± 7 | 1st part (43%)2nd part (57%) | Conservative (72%)Pylorotomy and drainage of the hematoma (14%)Pancreaticoduodenectomy with immediate reconstruction after failed angioembolization due to neoplasm of the head of the pancreas (14%) (image 1) | Postoperative anemia (14%)Paralytic ileus(14%) | 17 ± 9 |

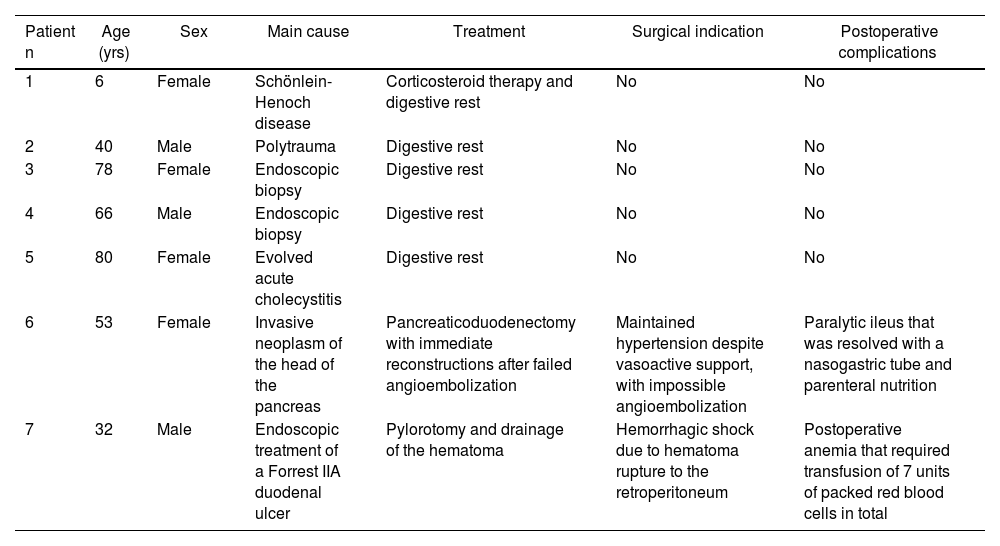

Causes of duodenal hematoma, treatment and postoperative complications of the series.

| Patient n | Age (yrs) | Sex | Main cause | Treatment | Surgical indication | Postoperative complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | Female | Schönlein-Henoch disease | Corticosteroid therapy and digestive rest | No | No |

| 2 | 40 | Male | Polytrauma | Digestive rest | No | No |

| 3 | 78 | Female | Endoscopic biopsy | Digestive rest | No | No |

| 4 | 66 | Male | Endoscopic biopsy | Digestive rest | No | No |

| 5 | 80 | Female | Evolved acute cholecystitis | Digestive rest | No | No |

| 6 | 53 | Female | Invasive neoplasm of the head of the pancreas | Pancreaticoduodenectomy with immediate reconstructions after failed angioembolization | Maintained hypertension despite vasoactive support, with impossible angioembolization | Paralytic ileus that was resolved with a nasogastric tube and parenteral nutrition |

| 7 | 32 | Male | Endoscopic treatment of a Forrest IIA duodenal ulcer | Pylorotomy and drainage of the hematoma | Hemorrhagic shock due to hematoma rupture to the retroperitoneum | Postoperative anemia that required transfusion of 7 units of packed red blood cells in total |

Symptoms are nonspecific, with a predominance of abdominal pain and signs of upper intestinal obstruction. Less frequent forms of presentation include hematemesis, jaundice or pancreatitis due to obstruction of the ampulla of Vater, while the most serious complication, hypovolemic shock, is due to its rupture.3 Although the most frequent causes are abdominal trauma injuries and spontaneous presentations due to anticoagulation,1 most of our cases were caused by endoscopic procedures. The imaging test of choice is abdominal computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast, which is also key in the differential diagnosis with duodenal perforation. Abdominal ultrasound can be useful in follow-up and as an initial diagnostic approach.4

Usually, the hematoma is located in the submucosal layer of the duodenum as a result of slow bleeding. The duodenal lumen, mesentery and retroperitoneal space can also be affected by diffusion. Hematomas secondary to abdominal trauma are usually focal and small in extension, affecting the third part of the duodenum more frequently due to the absence of the mesentery and a crushing mechanism against the spine.5 Spontaneous hematomas usually reach larger sizes. A descriptive study published by Abbas et al5 reported a mean spontaneous duodenal hematoma size of 23 cm. This larger size facilitates the differential diagnosis with tumor lesions.

In stable patients, the recommended approach includes initial conservative treatment with a nasogastric tube, bowel rest and nutritional support, which worked in 5 of our patients. In most cases, the hematoma spontaneously reabsorbs in 1–8 weeks after diagnosis, and radiological re-evaluation is recommended after 2 weeks. Patients with pseudoaneurysm of the pancreatoduodenal vessels or active bleeding can be treated by transarterial embolization or surgery if this technique is not available or if it fails.6

Therefore, surgical treatment is usually indicated for: situations of intraluminal hemorrhage not controlled by less invasive methods, cases associated with duodenal perforation, when signs of intestinal ischemia is demonstrated by CT, when the origin is tumor-related, and when there is no clinical-radiological improvement after 10–14 days of evolution.7–9 Exploratory laparotomy has shown greater sensitivity than CT to diagnose early complications derived from the hematoma, while shortening hospital stay and accelerating definitive treatment.9 The choice of technique is controversial and varies depending on the patient’s clinical status and intraoperative findings. In some cases, laparoscopic drainage may be sufficient. However, in the most extreme cases, damage-control surgery has been initially used to control bleeding with a subsequent definitive surgery once the patient has been hemodynamically stabilized,10 or even pancreaticoduodenectomy, as in our patient with extensive duodenal lesion and the presence of a pancreatic neoplasm causing obstructive jaundice. Other authors have also resorted to this technique, including Koichopolos et al.,7 who perform it in 2 stages for duodenal perforation due to necrosis in the context of an intramural hematoma secondary to pancreatitis, or Molina-Bare et al.,8 who use it for definitive treatment of a perforated duodenal tumor, with immediate reconstruction.

In conclusion, intramural duodenal hematoma is a rare abdominal emergency, whose diagnostic test of choice is CT. Conservative treatment is usually successful, and surgical treatment is not standardized.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from public, commercial or non-profit entities.