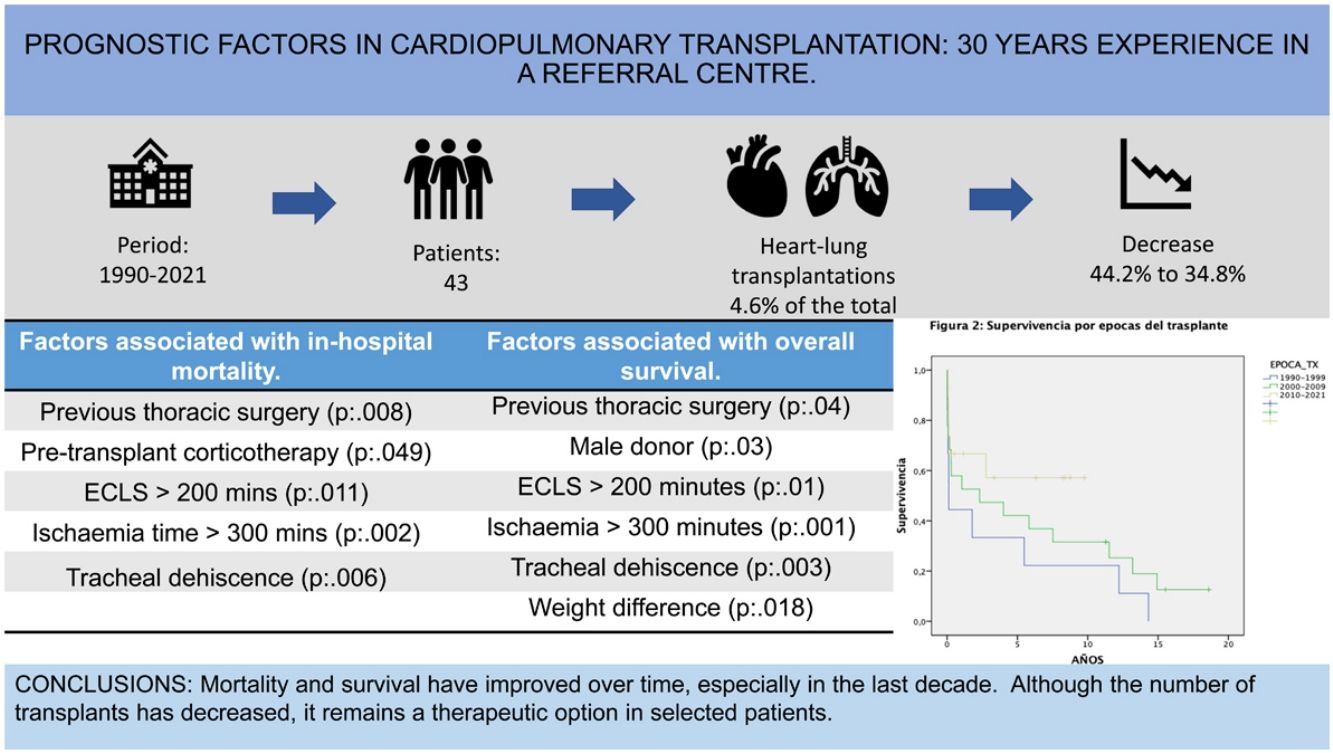

Heart-lung transplantation has shown a progressive decrease in the number of procedures. There is a lack of information about this field in Spain. The main goal of this study is to analyze the experience of a national reference hospital.

MethodsWe performed a retrospective study of a historical cohort of heart-lung transplanted patients in a single center, during a 30 years period (from 1990 to 2021). The associations between variables were evaluated using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Survival was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method. Differences were evaluated using the log-rank test and multivariate analysis with the Cox method.

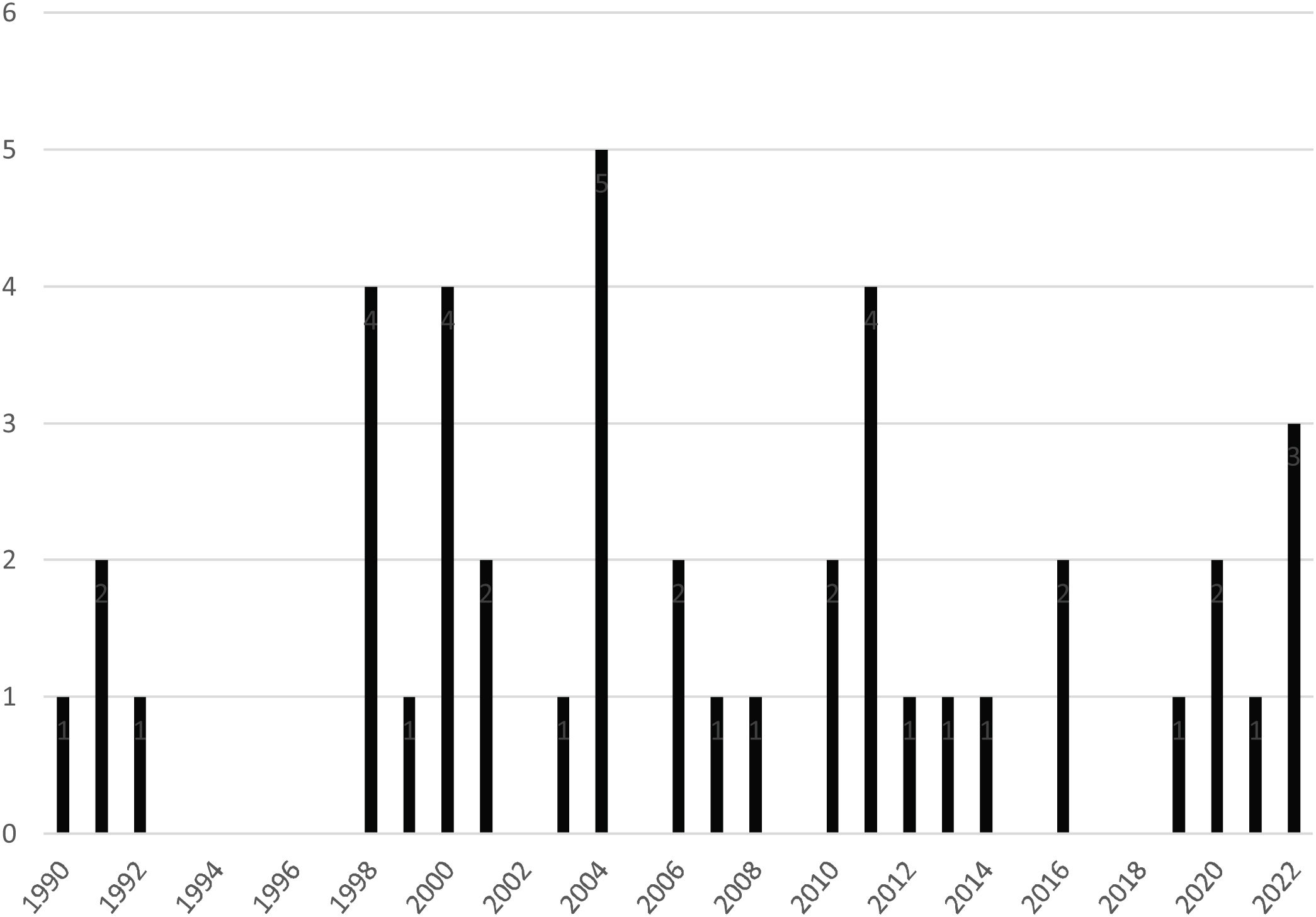

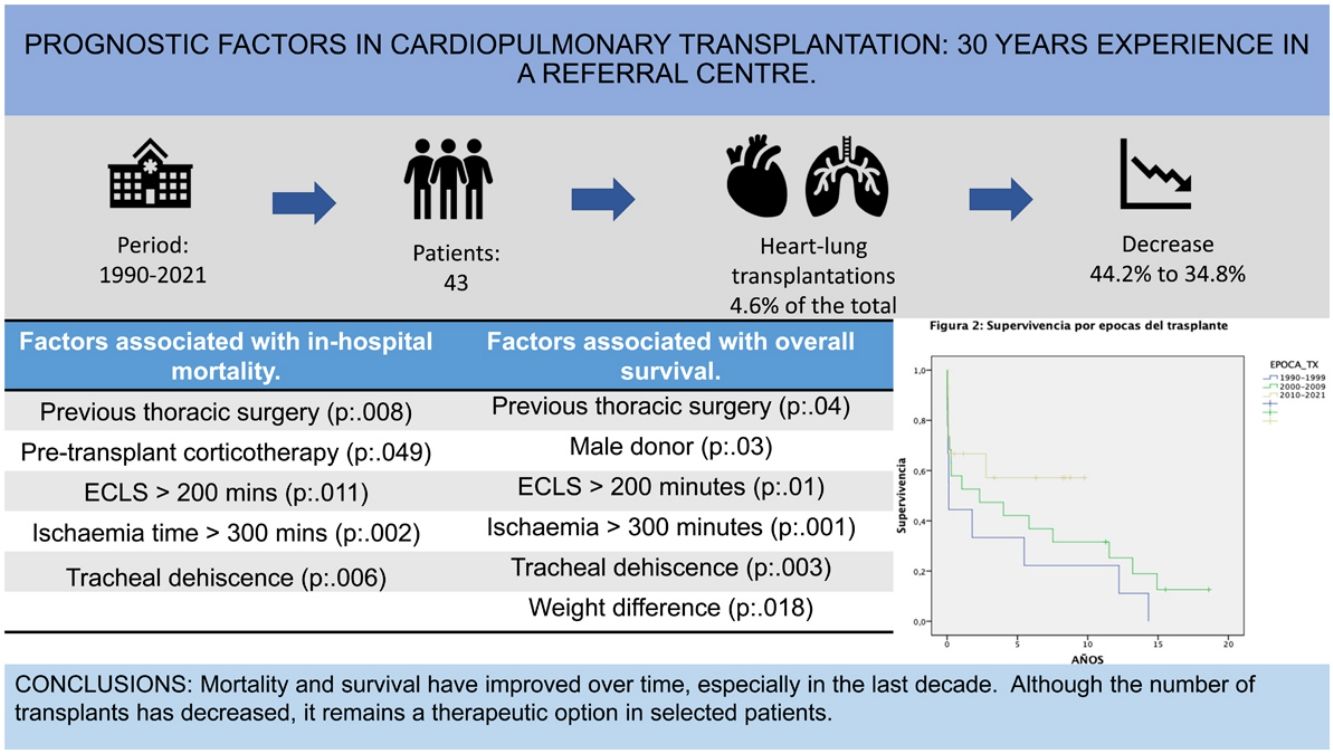

ResultsA decrease in the number of procedures performed in the last decade was observed [2000−2009: 19 procedures (44.2%); 2010−2021: 15 procedures (34.8%)]. Early postoperative mortality was 23.3%, falling to 13.3% from 2010. In-hospital mortality was 41%, falling to 33% from 2010.

Main factors related to higher mortality: previous thoracic surgery, corticosteroid therapy, extracorporeal circulation (ECLS) greater than 200 min, ischemia time greater than 300 min, and tracheal dehiscence (p < 0.005).

Overall survival at one, five, and ten years was 58%, 44.7%, and 36.1%, respectively. Factors associated with lower survival rates: previous thoracic surgery, male donor, extracorporeal circulation greater than 200 min, ischemia time greater than 300 min, tracheal dehiscence and weight difference (p < 0.005).

ConclusionsThere has been a progressive decrease in the number of heart-lung transplantations, being more evident in the last decade, but showing an improvement in both mortality and survival.

El trasplante cardiopulmonar ha presentado una disminución progresiva en el número de procedimientos. En nuestro país existe poca información al respecto, siendo el objetivo de este estudio analizar la experiencia de un hospital de referencia.

MétodosEstudio Observacional unicéntrico de una cohorte histórica en el periodo entre 1990 y 2021. Las asociaciones entre categorías se evaluaron mediante la prueba de χ2 o la prueba exacta de Fisher. La supervivencia se analizó mediante el método de Kaplan–Meier. Las diferencias se evaluaron mediante el test de log-rank, el análisis multivariante con el método de Cox.

ResultadosSe observó una reducción del número de procedimientos realizados en el último decenio [2000−2009:19 procedimientos (44,2%); 2010−2021:15 procedimientos (34,8%)]. La mortalidad postoperatoria precoz fue del 23,3%, reduciéndose al 13,3% a partir del 2010. La intrahospitalaria fue del 41%, reduciéndose al 33% a partir del 2010.

Los factores asociados a la mortalidad: cirugía torácica previa, corticoterapia, circulación extracorpórea mayor a 200 minutos, tiempo de isquemia mayor a 300 minutos y dehiscencia traqueal (p < 0,005).

La supervivencia global al año, cinco y diez años fue del 58%, 44,7%, 36,1% respectivamente. Los factores asociados a menores tasas de supervivencia fueron cirugía torácica previa, donante masculino, circulación extracorpórea mayor 200 minutos, tiempo de isquemia mayor a 300 minutos, dehiscencia traqueal y diferencia de pesos. (p < 0,005).

ConclusionesExiste una disminución en el numero de procedimientos, siendo mas evidente en la ultima década, pero evidenciando una mejora tanto de la mortalidad postoperatoria y supervivencia.

Since its inception in Stanford in 1982, heart-lung transplantation (HLT) has been a therapeutic option for patients with end-stage heart and lung disease, and has shown good long-term survival.1

The 2019 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) report lists a total of 4,884 HLTs from 1988 to 30 June 2018, of which 4,128 were performed in adults and 733 in the paediatric age group.2,3

The number of HLTs peaked in 1989 with an average of 200 transplants per year, and has progressively decreased to an average of 50 transplants per year over the last decade.3

The main reason for this progressive decrease has been that similar survival rates have been demonstrated after bilateral-lung transplantation (BLT)4–8 in patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH), given the improvement in right ventricular function after lowering pulmonary pressures.4,6,9

Similarly, in patients with heart disease and Eisenmenger's syndrome (ES), new therapies for PH and heart failure may prolong survival without the need for HLT.10–12

This reduction in indication for HLT is also evident in Spain according to data from the National Transplant Organisation in 2021; our hospital has the highest volume in the country.13

Over the years, the indications for HLT have changed. Idiopathic pulmonary hypertension (IPH) was the most common indication in the early years of transplantation, followed by congenital heart disease (CHD), and cystic fibrosis (CF). Currently, CHD complicated by ES has become the most common indication, followed by IPH.3,14 It is also indicated in patients with end-stage lung disease and left ventricular failure refractory to treatment, fibrosis, or right ventricular infarction with ventricular failure,11,15–18 and in patients with ES with severe CHD, failed repair of or uncorrectable CHD, and severe left ventricular failure.10,14 Finally, it should be considered in patients with severe PH refractory to clinical treatment.17–19

The latest ISHLT consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates describes indications for patients with advanced heart and lung disease who are not suitable for isolated heart or lung transplantation.15

The outcomes of HLT have progressively improved, with a median survival of 3.7 years in the 1990s and 6.5 years in the recent era (p = .025).3

The aim of this study is to analyse the experience of HLT in a tertiary care centre from its inception to the present day, and to identify the prognostic variables that condition postoperative morbidity and mortality, and survival.

MethodsDesignA single-centre observational study of a historical cohort of patients undergoing HLT in a national reference hospital in lung and heart-lung transplantation.

PatientsForty-three patients who underwent HLT in the period between 1990 and 2021 were included in the study. Adult and paediatric patients were included. All indications were decided in a multidisciplinary committee. The ethics committee of the hospital approved this study.

VariablesStudy variables included demographic data such as age (mean and range), sex, weight, height, body mass index (kg/m2), blood group, history of previous thoracic surgery, corticosteroid treatment, primary diagnosis, and indication for HLT classified according to the latest consensus on PH,20 baseline, pre-transplant patient status (NYHA scale), respiratory function tests (forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO), cardiac function tests measured by echocardiogram and cardiac catheterisation, and donor variables (age, sex, height, weight, arterial oxygen pressure).

Surgical procedure variables included ischaemia time and extracorporeal circulation (ECLS) time.

The postoperative outcomes analysed were postoperative surgical and clinical complications: primary lung graft dysfunction (PLGD),21 length of stay in resuscitation unit and hospital stay (days), 30-day perioperative mortality, in-hospital mortality, and survival.

Statistical analysisFilemaker® and SPSS® were used for data collection and statistical analysis.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD if normally distributed or as median otherwise. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Associations between categories were assessed using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, when necessary. We used the student's t-test or Man–Whitney U-test. Survival was analysed using the Kaplan–Meier method. Differences in survival were assessed using the log-rank test, and multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox method. A p < .05 was considered significant.

ResultsRecipient and donor characteristicsA total of 43 HLTs were performed, representing 4.6% of all lung transplants and HLTs performed in the period 1990–2021 (n = 917).

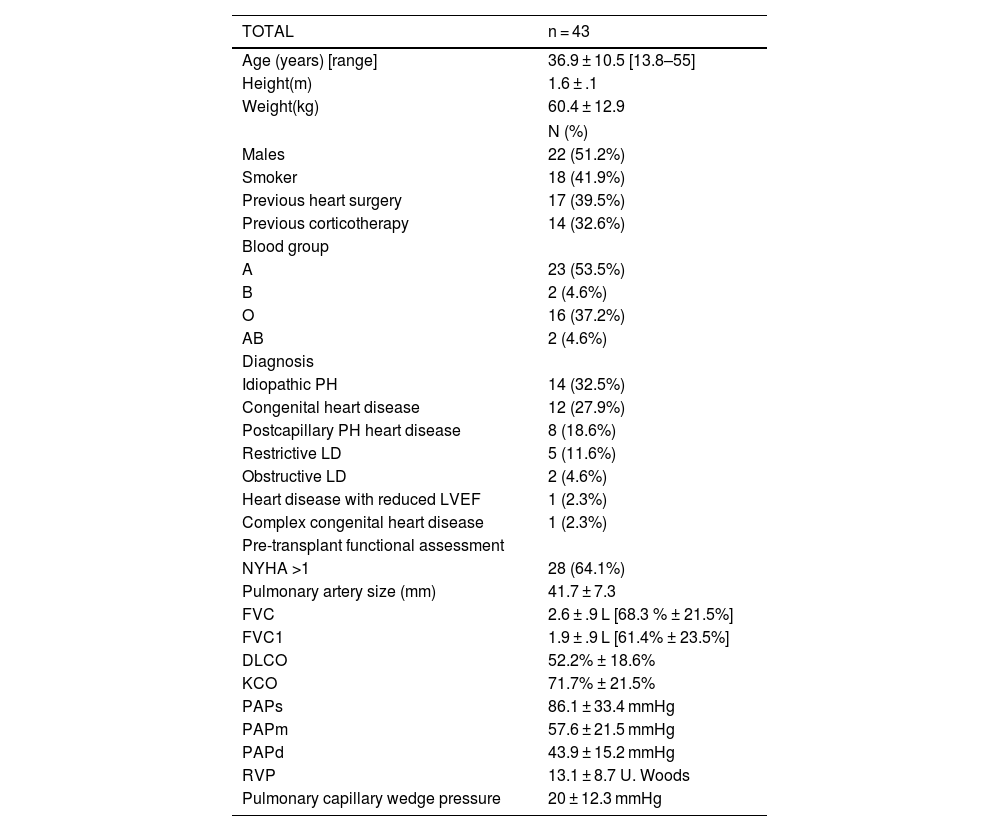

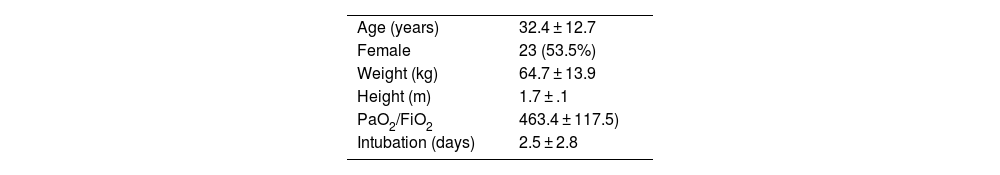

Demographic and baseline recipient characteristics, and preoperative functional assessment are described in Tables 1 and donor characteristics are described in Table 2.

Demographic and preoperative characteristics.

| TOTAL | n = 43 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) [range] | 36.9 ± 10.5 [13.8–55] |

| Height(m) | 1.6 ± .1 |

| Weight(kg) | 60.4 ± 12.9 |

| N (%) | |

| Males | 22 (51.2%) |

| Smoker | 18 (41.9%) |

| Previous heart surgery | 17 (39.5%) |

| Previous corticotherapy | 14 (32.6%) |

| Blood group | |

| A | 23 (53.5%) |

| B | 2 (4.6%) |

| O | 16 (37.2%) |

| AB | 2 (4.6%) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Idiopathic PH | 14 (32.5%) |

| Congenital heart disease | 12 (27.9%) |

| Postcapillary PH heart disease | 8 (18.6%) |

| Restrictive LD | 5 (11.6%) |

| Obstructive LD | 2 (4.6%) |

| Heart disease with reduced LVEF | 1 (2.3%) |

| Complex congenital heart disease | 1 (2.3%) |

| Pre-transplant functional assessment | |

| NYHA >1 | 28 (64.1%) |

| Pulmonary artery size (mm) | 41.7 ± 7.3 |

| FVC | 2.6 ± .9 L [68.3 % ± 21.5%] |

| FVC1 | 1.9 ± .9 L [61.4% ± 23.5%] |

| DLCO | 52.2% ± 18.6% |

| KCO | 71.7% ± 21.5% |

| PAPs | 86.1 ± 33.4 mmHg |

| PAPm | 57.6 ± 21.5 mmHg |

| PAPd | 43.9 ± 15.2 mmHg |

| RVP | 13.1 ± 8.7 U. Woods |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure | 20 ± 12.3 mmHg |

Quantitative variables are expressed as mean and range.

DLCO: diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC: forced vital capacity; KCO: carbon monoxide transfer coefficient; LD: Lung disease; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; PAPd: diastolic pulmonary artery pressure; PAPm: mean pulmonary artery pressure; PAPs: systolic pulmonary artery pressure; PH: Pulmonary hypertension; PVR: peripheral venous resistance; RVEF: right ventricular ejection fraction.

Pretransplant indications and diagnoses are described in Table 1.

A reduction in the number of HLTs performed in the last decade of study was observed (Fig. 1).

Procedure and postoperative courseFive (11.6%) emergency transplantations were performed. The mean ischaemia time was 223 ± 69.7 min, with a mean ECLS time of 199.9 ± 71.3 min.

Mean hospital stay after transplantation was 46.8 ± 34.7 days and in resuscitation 17.1 ± 18.6 days, with a mean intubation time of 6.6 ± 8.4 days. Seven (16.2%) patients required readmission for resuscitation.

The most frequent postoperative complications were pleural effusion (32.5%), haemothorax (30.2%), and cardiogenic pulmonary oedema (30.2%). There were 12 cases of primary graft dysfunction of which 6 (13.9%) were grade 3. Ten patients required reoperation (23.2%); 7 (16.2%) for haemorrhage and 3 (7%) for surgical wound dehiscence.

Factors associated with early mortalityThe overall perioperative mortality of the series was 23.3% (n:10) decreasing to 13.3% from 2010. In-hospital mortality was 41.9%, decreasing to 33% from 2010.

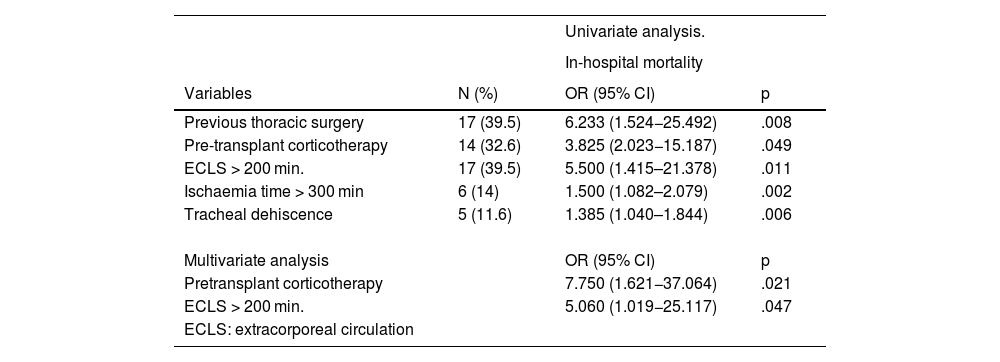

Factors associated with in-hospital mortality (univariate analysis) are described in Table 3. Multivariate analysis showed that pre-transplant corticosteroid therapy [OR: 7.750 (95% CI: 1.621−37.064), p = .021] and CPB > 200 min [OR: 5.060 (95% CI: 1.019−25.117), p = .47) were associated with mortality (Table 3). The most frequent causes of death were respiratory infection (18%) and surgical complications (haemorrhage and tracheal dehiscence, 9%).

Factors associated with in-hospital mortality.

| Univariate analysis. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality | |||

| Variables | N (%) | OR (95% CI) | p |

| Previous thoracic surgery | 17 (39.5) | 6.233 (1.524−25.492) | .008 |

| Pre-transplant corticotherapy | 14 (32.6) | 3.825 (2.023−15.187) | .049 |

| ECLS > 200 min. | 17 (39.5) | 5.500 (1.415–21.378) | .011 |

| Ischaemia time > 300 min | 6 (14) | 1.500 (1.082–2.079) | .002 |

| Tracheal dehiscence | 5 (11.6) | 1.385 (1.040–1.844) | .006 |

| Multivariate analysis | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Pretransplant corticotherapy | 7.750 (1.621−37.064) | .021 | |

| ECLS > 200 min. | 5.060 (1.019−25.117) | .047 | |

| ECLS: extracorporeal circulation |

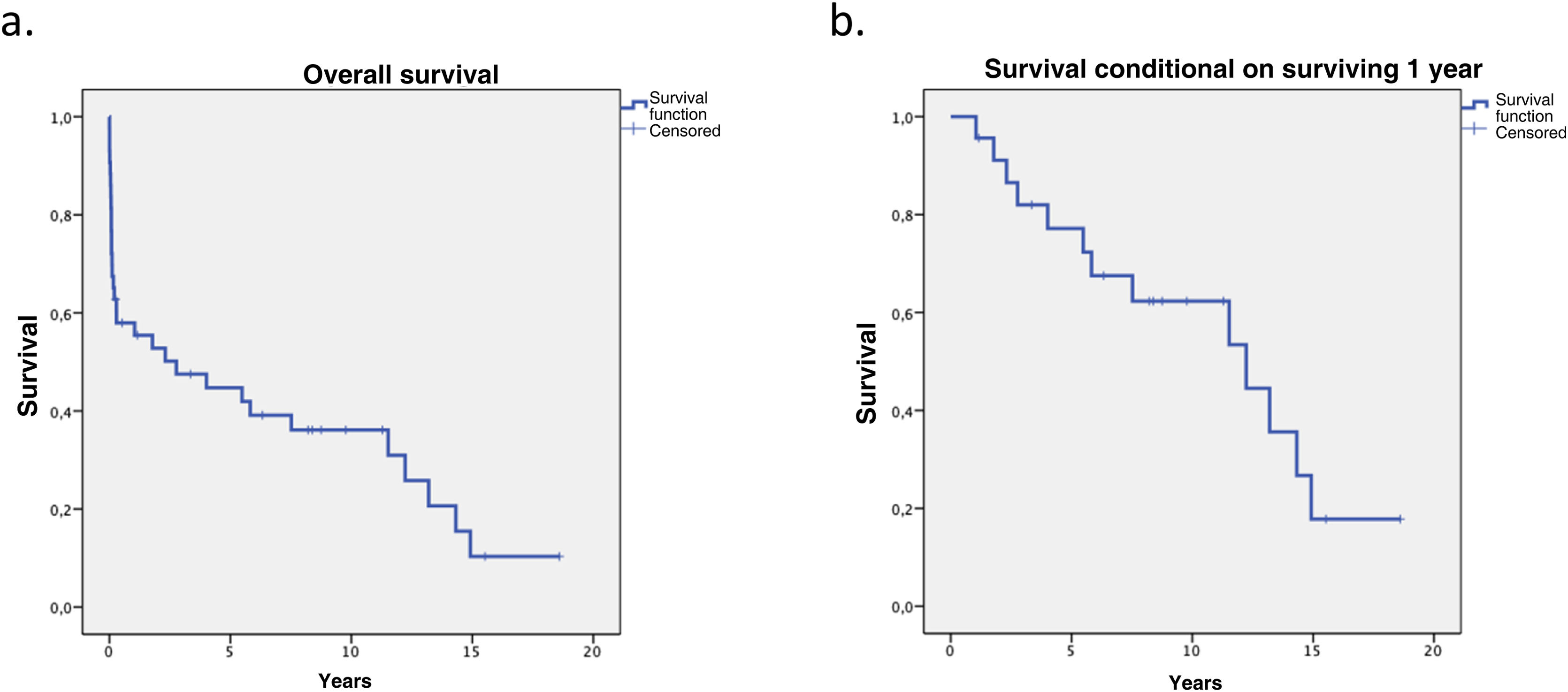

Overall survival at 1, 5, and 10 years was 58%, 44.7%, 36.1% respectively. When survival conditional on surviving the first year was analysed, survival at 5 and 10 years improved to 77.2% and 62.3% respectively, making the impact of the first year on long-term survival evident (Fig. 2).

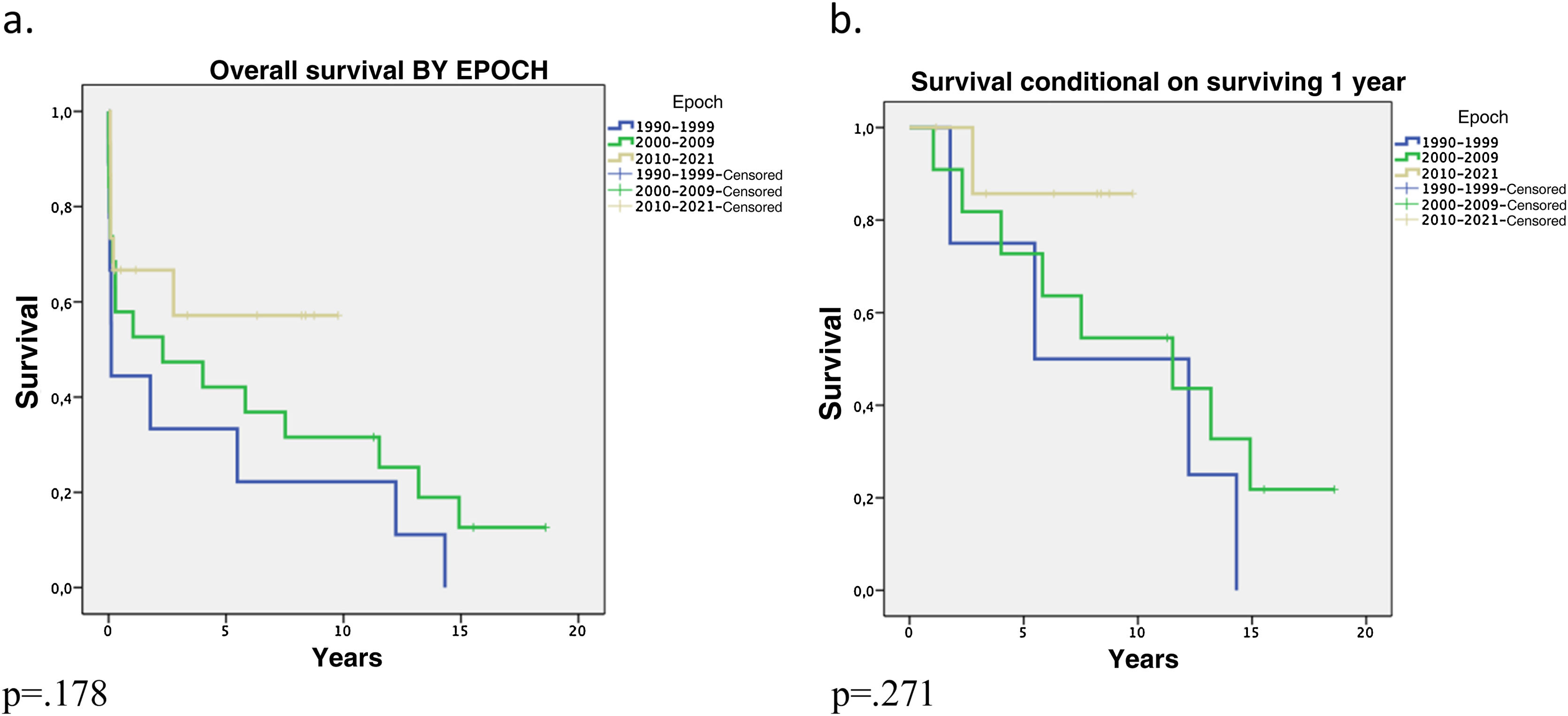

Survival by epoch at 1 and 5 years increased from 44.4% and 33.3%, in the 1990–1999 epoch to 66.7% and 57.1%, in the 2010–2020 epoch, (p = .178). The same trend was observed when survival was analysed by epoch conditional on surviving the first year, (p = .231) (Fig. 3).

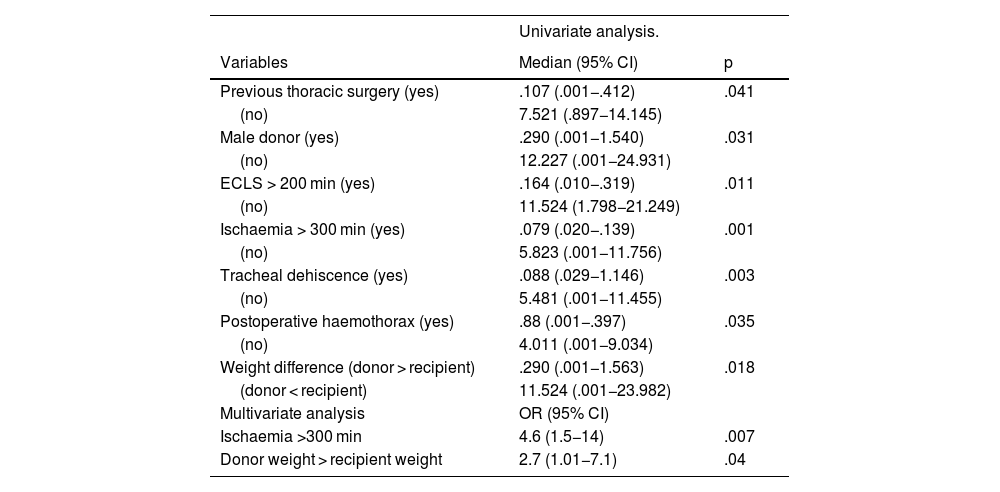

Factors associated with long-term survival are described in Table 4 (univariate analysis). Multivariate analysis showed that ischaemia greater than 300 min [OR:4.6 (95% CI:1.5−14) p = .007] and donor weight greater than recipient weight [OR:2.7 (95% CI:1.01−7.1) p = .04] negatively affected long-term survival.

Factors associated with survival.

| Univariate analysis. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Median (95% CI) | p |

| Previous thoracic surgery (yes) | .107 (.001−.412) | .041 |

| (no) | 7.521 (.897−14.145) | |

| Male donor (yes) | .290 (.001−1.540) | .031 |

| (no) | 12.227 (.001−24.931) | |

| ECLS > 200 min (yes) | .164 (.010−.319) | .011 |

| (no) | 11.524 (1.798−21.249) | |

| Ischaemia > 300 min (yes) | .079 (.020−.139) | .001 |

| (no) | 5.823 (.001−11.756) | |

| Tracheal dehiscence (yes) | .088 (.029−1.146) | .003 |

| (no) | 5.481 (.001−11.455) | |

| Postoperative haemothorax (yes) | .88 (.001−.397) | .035 |

| (no) | 4.011 (.001−9.034) | |

| Weight difference (donor > recipient) | .290 (.001−1.563) | .018 |

| (donor < recipient) | 11.524 (.001−23.982) | |

| Multivariate analysis | OR (95% CI) | |

| Ischaemia >300 min | 4.6 (1.5−14) | .007 |

| Donor weight > recipient weight | 2.7 (1.01−7.1) | .04 |

ECLS: extracorporeal circulation.

There has been a progressive reduction in the number of HLTs performed worldwide. According to the latest ISHLT report, the peak incidence was in 1989 with 229 transplants, falling to only 36 in 2015.3 Dimopoulos et al.10 reported a decrease in the rate of HLT in their global series from 34.9% before 2005 to 6.7% from 2006 onwards (p = .0001).

In our experience, this progressive reduction in the number of HLT has also been evident, currently standing at 1 procedure/year, with a progressive decrease in HLT rates with respect to the total number of transplants performed.

This trend towards a reduction in the indication for HLT is mainly due to the change in the procedures performed in patients with PH not secondary to CHD, where an improvement in ventricular function has been demonstrated by reducing pulmonary resistances after BLT,22,23 with the same results in terms of mortality and survival as HLT.4,6,24 However, this improvement is not evident after single-lung transplantation (SLT) in these cases.25,26

The indications for HLT have also changed over time. Currently, the main indication for HLT is non-idiopathic PH at 37.7%, followed by IPH at 28.4%, and in third place CF at 14.9%.3 The latter has become an uncommon indication today compared to the 1990s when 230 HLTs were performed for this disease.3,27

Similarly, in our study we were able to demonstrate the same trend in relation to indications, with 36.8% of transplants in the last decade involving CHD and 28.6% involving IPH.

One of the major early complications of lung transplantation is PGD, which occurs in up to 50% of lung recipients, in most cases mild and transient, but in up to 30% it can result in severe hypoxaemia.28 Several studies describe PGD as one of the main causes of early morbidity and mortality, requiring ventilatory support and measures such as mechanical ventilation, tracheotomy, or reintubation for its treatment.6,14,17 PGD in our study occurred in 27.9%, lower than that described by other authors, who describe a percentage of over 50%.14,17

Lung infections constitute further major complications,11 and are a significant cause of mortality.12–14 In our series, infectious complications occurred in 19 patients (44.2%), and were the cause of in-hospital death in 8.

In terms of surgical complications, those related to pleural pathology stand out, postoperative haemothorax being of great importance, frequently requiring reoperation. An increased incidence of haemorrhagic complications has been described in relation to anticoagulation and ECLS time during surgery. Hjortshøj et al.,12 report the need for reoperation in 20 (31.7%) patients, 95% of them due to postoperative bleeding. Similarly, Brouckaert et al.17 reintervened in 11 (28.9%) patients for postoperative haemorrhage, data similar to those presented in our study.

In-hospital mortality and mortality during the first year after HCT remains high, although a progressive improvement has been observed with the passage of time and accumulated experience.3,8,10 In our results we observed the same trend, with a progressive reduction of around 10% in mortality during this period with the development of the programme.

Fadel et al.,6 compare the results of HLT and BLT in PH and describe an overall hospital mortality rate of 19.6% and for HLT of 21.7%. Similarly, Brouckaert, et al.17 describe an overall in-hospital mortality rate of 19.1% and for HLT of 23.7%, Yun et al.14 report 20%, and Dawkins et al., 26%.29

These results highlight the importance of the perioperative period, as this is when most deaths occur, whether due to PPGD, surgical complications, or non-cytomegalovirus infections.3,11

The ISHLT describes as independent risk factors for mortality, the era the PT was performed, dependence of the recipient on mechanical ventilation, advanced age of the patient, and cytomegalovirus serology discordance.3 Dimopoulos et al.10 compare HLT and heart transplantation in patients with congenital heart disease and describe advanced age, HLT, and transplantation before 2006 as predictors of mortality. In our series we observed that previous thoracic surgery, ECLS time greater than 240 min, organ ischaemia time greater than 300 min, corticotherapy, and tracheal dehiscence influenced in-hospital mortality.

Overall survival in our series was 58%, 44.7%, 36.1% at 1, 5, and 10 years respectively, slightly lower than that reported by ISHLT.27 When survival conditional on surviving the first year was analysed, the results improved to 77.2% and 62.3% at 5 and 10 years respectively, showing the impact of the first year on long-term survival.

As described in other studies,17,23,30 the impact of the epoch in which the HLT was performed was also present in our series. In the last 10 years, survival improved to 66.7% and 57.1% at 1 and 5 years, respectively. Brouckaert et al.17 describe significantly better survival for patients transplanted in 2011–2014 compared to the 1990s (p = .03). Toyoda et al.5 found significantly better actuarial survival in the group transplanted between 1994 and 2006 compared to 1982 and 1993 (p = .004). This improvement in survival of patients undergoing HLT can probably be attributed to improvements in surgical techniques, the development of organ preservation solutions, better patient selection, better development of immunosuppression and antibiotic prophylaxis, as well as perioperative care, and multidisciplinary management.11,17,19

Other factors affecting long-term survival have been described, such as diagnosis of IPH and donor-recipient weight difference.3 Fadel et al.6 in one of the largest studies on HLT, define previous surgery, presence of preoperative renal dysfunction, PGD and BOS as prognostic factors for survival. In our series, male donor, ECLS and prolonged ischaemia time, haemothorax, tracheal dehiscence, and lower recipient-donor weight difference had a negative influence on survival, with prolonged ischaemia time and recipient-donor weight difference remaining as prognostic factors in the multivariate analysis.

The main limitations of this study were due to the nature of its design, as it was a retrospective study with a relatively small number of patients, reducing the power of the analysis.

In conclusion, we observed a progressive decrease in the number of procedures, secondary to changes in indications and a significant improvement in early mortality and survival of HLT in the last decade. Recipient factors such as a history of previous surgery and corticosteroid use, procedural factors such as excessive prolongation of ischaemia and ECLS times, and the presence of severe complications (haemothorax and tracheal dehiscence) negatively affected early mortality and long-term survival. Some donor-related variables (male sex and larger size) negatively impacted long-term survival. HLT remains an effective treatment option in highly selected patients.

Author contributionsC. Ordoñez confirms that the first three authors of this article have made substantial contributions to the creation and design of the study, and to the acquisition of data, interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. They all approved the final version of the paper.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

FundingNo funding was received for this work.