The SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic requires an analysis in the field of oncological surgery, both on the risk of infection, with very relevant clinical consequences, and on the need to generate plans to minimize the impact on possible restrictions on health resources.

The AEC is making a proposal for the management of patients with hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) malignancies in the different pandemic scenarios in order to offer the maximum benefit to patients, minimising the risks of COVID-19 infection, and optimising the healthcare resources available at any time. This requires the coordination of the different treatment options between the departments involved in the management of these patients: medical oncology, radiotherapy oncology, surgery, anaesthesia, radiology, endoscopy department and intensive care.

The goal is offer effective treatments, adapted to the available resources, without compromising patients and healthcare professionals’ safety.

La pandemia por SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) obliga a una reflexión en el ámbito de la cirugía oncológica, tanto sobre el riesgo de infección, de consecuencias clínicas muy relevantes, como sobre la necesidad de generar planes para minimizar el impacto sobre las posibles restricciones de los recursos sanitarios.

La AEC hace una propuesta de manejo de pacientes con neoplasias hepatobiliopancreáticas (HBP) en los distintos escenarios de pandemia, con el objetivo de ofrecer el máximo beneficio a los pacientes y minimizar el riesgo de infección por COVID-19, optimizando a su vez los recursos disponibles en cada momento. Para ello es preciso la coordinación de los diferentes tratamientos entre los servicios implicados: oncología médica, oncología radioterápica, cirugía, anestesia, radiología, endoscopia y cuidados intensivos.

El objetivo es ofrecer tratamientos eficaces, adaptándonos a los recursos disponibles, sin comprometer la seguridad de los pacientes y los profesionales.

Cancer patients present a state of systemic immunosuppression, derived from the underlying neoplastic process and the treatments administered, thus demonstrating greater susceptibility to infections. The management of this group of patients presents two major problems to contemplate in the current situation of the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. First, cancer patients have a greater risk of becoming infected, with higher morbidity and mortality rates associated with surgery.1,2 Second, the limitation of resources at certain times requires their use to be prioritized for more critical patients.

Generally, the management of patients with hepatobiliary-pancreatic (HBP) cancer is complex, and it is necessary for the Multidisciplinary Committee (MC) to design the most appropriate therapeutic strategy. In the current context, it is also essential to minimize the risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2 in these patients, as well as to optimize the treatments and available resources in order to offer the best and safest alternatives. All decisions must be agreed upon in the MC, knowing full well that at certain moments it may be necessary to modify standard protocols. It is important to establish action plans that contemplate the prioritization, delay and even cancellation of different cancer treatments.

Perioperative screening for SARS-CoV-2 infection in hepatobiliary-pancreatic cancer patientsThe data from the existing literature1,2 indicate that cancer patients have a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, developing major complications, and death. Yu et al. describe the incidence and results in a cohort of cancer patients at a tertiary centre in Wuhan, reporting a mortality rate in this group of 25%.3

It is important to maximize protection against infection in these patients to avoid the high morbidity and mortality. In addition, necessary measures must be taken for the protection of healthcare personnel. Health institutions must be committed to providing the resources in order to apply the prevention measures established by current regulations.4

The current recommendation is to screen cancer patients for SARS-CoV-2 virus infection 24−48 h before receiving chemotherapy/radiotherapy or undergoing surgical interventions, and to advise them to limit contacts or self-isolate.

Screening for infection should be based on clinical, epidemiological, analytical, serological and microbiological criteria using COVID-19 tests (polymerase chain reaction or PCR/serological antibody detection). If no test is available and there is a high suspicion of infection, a chest computed tomography (CT) scan may be used in the 24−48 h prior to surgery.5

If the patient presents COVID-19 infection and the surgery cannot be postponed, the entire surgical team must use personal protective equipment (PPE), which must be provided by the workplace. These PPE will consist of a waterproof gown, N95 or FFP2/FFP3 masks, goggles, a face shield, long nitrile gloves (one pair), a cap and footwear used exclusively in the area, without perforations.4

In the event that surgery is scheduled, and the patient has no proven SARS-CoV-2 infection or suspected contact, a ‘clean circuit’ is established in the hospital to preserve patient safety and minimize the risk of infection.5

Evaluation of hepatobiliary-pancreatic cancer patients in the context of COVID infectionIn the current exceptional context, and depending on the impact of the pandemic and the level of alert at each hospital, it may be necessary to modify the protocols. In addition to the usual factors, there are the added concerns of the availability of resources, hospital bed occupancy, and the fact that the patient may have SARS-CoV-2 infection. Therefore, a thorough evaluation of the patient, disease, surgical team, hospital resources and healthcare area are necessary.

In this situation, the scheduling of adjuvant, neoadjuvant, surgical and other treatments will be based on criteria for maximum benefit, compared to the minimization of the risks of infection by SARS-CoV-2, and optimizing the available resources at all times.6,7 The different services involved will be coordinated: medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgery, anaesthesia, intensive care, radiodiagnosis and endoscopy.

The objective will always be patient safety, without compromising the efficacy of the oncological treatments.

The following factors should be examined:

Patient factors: assess the risk/benefit with regards to exposure to coronavirus and its potential consequences versus other therapeutic alternatives.6,7

- •

Age

- •

Frailty criteria (Questionnaire G8 < 14)8

- •

Moderate, severe or total dependence (Barthel <55)9

- •

Moderate or severe cognitive impairment (Pfeiffer survey >5)10

- •

Associated comorbidities (Charlson Index >3)11

- •

Functional situation of the patient (ECOG)12

Neoplastic disease factors: clinical tumour staging (cTNM), taking into account the biology (doubling time, estimated growth rate, risk of progression to disseminated disease) and the symptoms caused.6

Degree of immunosuppression: induced by the type of treatment chosen (neoadjuvant or adjuvant) or other causes (immunodeficiencies, immunosuppressive treatments, malnutrition, tumour disease itself). Regimens that limit the number of hospital visits are preferred, as well as the oral route over intravenous. Short regimens are for cases agreed upon by the MC.

SARS-CoV-2 infection present or not: in patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection, it is recommended to not administer chemotherapy treatments; the same holds true for patients who have had recent contacts until the absence of infection is guaranteed.6 In the case of radiotherapy, this should be evaluated on an individual basis.13 Patients who must undergo elective surgery without delay, with a high suspicion of infection, will undergo COVID-19 tests (PCR or serological test) according to the protocols established at each hospital.4 In the case of a confirmed positive patient, PPE is used together with surgical clothing, which ensures adequate protection for surgeons. The sterile equipment necessary for surgery will be worn over the PPE. A check list of the entire procedure will be followed, which explicitly includes the patient’s COVID-19 situation.4

Available healthcare resources: optimize treatments in the context of number of infections registered and the resources available, which may be different between healthcare areas and even geographical areas:

- •

Percentage of patients admitted with COVID-19.

- •

Emergency department areas for respiratory patients vs other patients.

- •

Availability of operating rooms.

- •

Availability of ventilators.

- •

Availability of critical care/resuscitation beds.

Estimated resource consumption: it will be important to make an estimate of the hospital resources that will be necessary, such as the need for postoperative Intensive Care Unit (ICU) stay, calculation of the mean hospital stay, morbidity associated with the most frequent surgery, etc.

Surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy in the context of COVIDTherapeutic decisions will be made in MC with two objectives: to offer the best therapeutic alternative to the patient’s neoplastic process and to limit the patient’s exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Regarding the laparoscopic approach, although previous research has shown that certain blood-borne viruses could spread through aerosol-producing procedures,14 in the case of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, this form of dissemination is still controversial, and there is insufficient scientific evidence. Thus, the AEC (Spanish Association of Surgeons)15 and the SAGES (Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons)16 do not advise against its use, when indicated. However, it is necessary to take the pertinent precautionary measures (low-pressure pneumoperitoneum, continuous evacuation of smoke in a closed circuit, complete suction of the pneumoperitoneum at the end of the procedure) and use the pertinent protective equipment to effectively avoid the infection of medical professionals.

The ACS (American College of Surgeons) mentioned that aerosol-generating procedures could increase the risk for operating room personnel. However, the current lack of evidence prevents making a clear recommendation or advising against minimally invasive surgery,17 while the benefits of this approach reduce postoperative morbidity and hospital stay.

When radiotherapy is indicated, hypofractionation schemes are recommended whenever possible. These schemes allow for shorter treatments, with a toxicity similar to conventional treatments and equal or better treatment efficacy. In this way, the patient stay in the hospital will be limited, minimizing the possible risk of infection, both for patients and medical personnel. The decision to start or continue radiotherapy treatment in patients with active SARS-CoV-2 infection must be made individually and by consensus.13

The general recommendations for the administration of chemotherapy in its different modalities is, according to the SEOM-TTD-GEMCAD,6 not to administer treatments in patients with suspected infection or a history with risk of contact of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and patients should be screened for infection before starting any treatment. In general, the established recommendations include prioritization of (neo) adjuvant treatments in high-risk cancer patients in whom a significant survival benefit is expected. Regimens or schedules that reduce the number of hospital visits are also recommended (biweekly or every 3 weeks, rather than weekly, and oral rather than intravenous administration). Short schedules for chemotherapy treatment must be agreed upon with radiation oncologists.6 The use of primary prophylaxis with G-CSF is also recommended in regimens with a risk of febrile neutropenia ≥10%–15%.

Restructuring the activityGeneral considerations for HBP cancer patientsRecently, different studies have been published that show how the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has had a negative impact on the therapeutic management of patients with HBP neoplasms.18,19 Usually, the complexity of these interventions exposes patients to postoperative complications, which can be more or less frequent, depending on the patient volume of the hospitals. Volume-outcome relationships in HBP surgery are well established, with a shorter hospital stay and lower mortality in high-volume hospitals.20,21

Morbidity rates reported in liver surgery are from 10% to 15%22–24 and are even higher in pancreatic surgery, with morbidity rates >50% and reoperation rates close to 10%.25–29 Some complications (biliary fistulae, pancreatic fistulae, abscesses) lead to long hospital stays, which sometimes require invasive measures or surgical reinterventions. Together with the high risk of serious postoperative complications reported3,30 in positive COVID-19 patients, this may make it necessary to postpone surgery and modify cancer treatments.3,30 For this reason, complex HBP surgery, in high-risk patients, should not be performed in low-volume centres during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the aim of reducing long hospital stays and major complications that require ICU care.31

In addition, it is important to establish a system for prioritizing patients on the waiting list. The AEC management document for return to normalcy recommends the adapted scoring scale from Pranchard et al. Thus, patients with a cumulative score of 60 or less will be considered suitable for the benefit of surgery.5

In the event of limited resources, possible referral to another hospital will be considered.

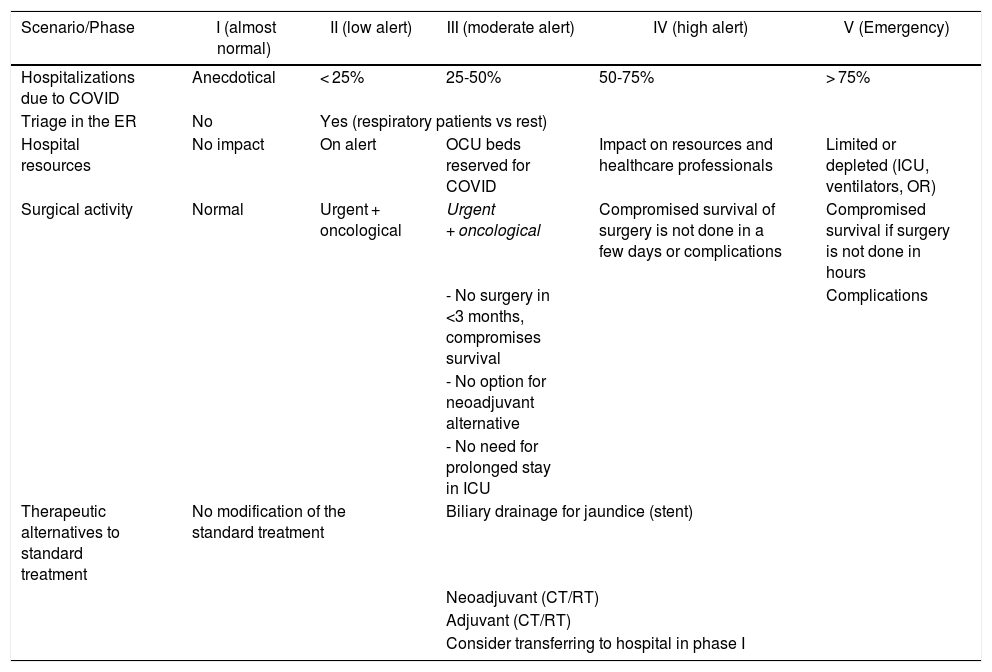

Scenarios/phases of the pandemicThe organization of the oncological surgical activity32 will be determined by the scenario of the pandemic in which we find ourselves. The AEC proposes a scale that dynamically defines 5 phases in the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1), taking into account its curve.33

Scenarios of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

| Scenario/Phase | I (almost normal) | II (low alert) | III (moderate alert) | IV (high alert) | V (Emergency) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalizations due to COVID | Anecdotical | < 25% | 25-50% | 50-75% | > 75% |

| Triage in the ER | No | Yes (respiratory patients vs rest) | |||

| Hospital resources | No impact | On alert | OCU beds reserved for COVID | Impact on resources and healthcare professionals | Limited or depleted (ICU, ventilators, OR) |

| Surgical activity | Normal | Urgent + oncological | Urgent + oncological | Compromised survival of surgery is not done in a few days or complications | Compromised survival if surgery is not done in hours |

| - No surgery in <3 months, compromises survival | Complications | ||||

| - No option for neoadjuvant alternative | |||||

| - No need for prolonged stay in ICU | |||||

| Therapeutic alternatives to standard treatment | No modification of the standard treatment | Biliary drainage for jaundice (stent) | |||

| Neoadjuvant (CT/RT) | |||||

| Adjuvant (CT/RT) | |||||

| Consider transferring to hospital in phase I | |||||

Based on these phases, we have established a series of recommendations in the field of HBP cancer surgery, considering the affected organ and the type of neoplasm.

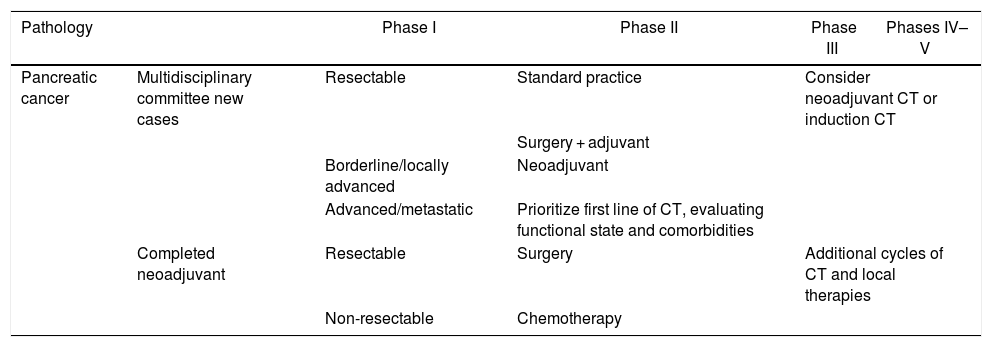

Therapeutic recommendations for oncological surgery of the pancreas and periampullary areaThe following recommendations are established (Table 2):

Recommendations for management of pancreatic cancer according to pandemic phases.

| Pathology | Phase I | Phase II | Phase III | Phases IV–V | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic cancer | Multidisciplinary committee new cases | Resectable | Standard practice | Consider neoadjuvant CT or induction CT | |

| Surgery + adjuvant | |||||

| Borderline/locally advanced | Neoadjuvant | ||||

| Advanced/metastatic | Prioritize first line of CT, evaluating functional state and comorbidities | ||||

| Completed neoadjuvant | Resectable | Surgery | Additional cycles of CT and local therapies | ||

| Non-resectable | Chemotherapy | ||||

If the patient presents jaundice, consider biliary drainage.

For patients with obstructive jaundice, biliary drainage (endoscopic or percutaneous) will be performed when a delay in surgery is anticipated.

Local/resectable pancreatic cancer34- •

Phases I–II: surgery and start of adjuvant chemotherapy following the standard protocol of the hospital35

- •

Phases III–V: drainage in the presence of jaundice or, if it is anticipated, postponement of surgery whenever possible until the hospital is in phase I-II. Neoadjuvant treatment and re-evaluation for surgery as soon as possible or referral to another hospital.

- •

Phases I–V: based on functional status and comorbidity, a neoadjuvant scheme will be considered.35 Depending on the hospital, neoadjuvant treatment with induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy (CRT) may be considered depending on the tolerance/response obtained and the surgical waiting list.

- •

Phases I–V: depending on functional status and comorbidities, the initiation of a first line of chemotherapy will be prioritized. The start of a second line is determined by the functional status and response/tolerance of the first line.

It is recommended to postpone surgery for premalignant pancreatic diseases, including intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) and pNET.

Exceptions include symptomatic pNET without effective alternative treatment options, or pNET or IPMN with suspected malignancy, in which case it should be treated as a resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas.21

Ampullary and duodenal adenocarcinomaBecause the evidence available to date on the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy is limited for this type of neoplasm and it cannot be considered a stable disease, surgical resection is recommended, assuming the pandemic phase allows and healthcare resources are available.

In the presence of complications, such as bleeding or obstruction, endoscopic treatment to control bleeding or placement of a duodenal stent for obstruction may be attempted until surgery can be performed.

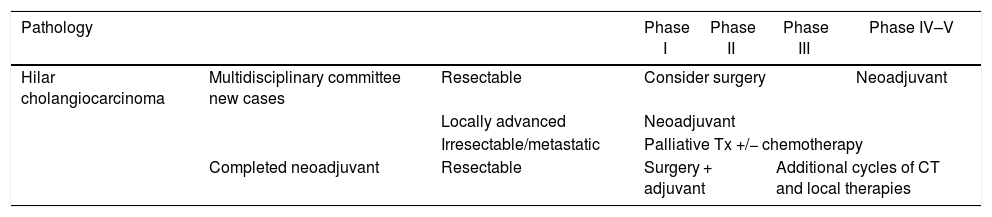

Therapeutic recommendations for oncological surgery of hilar cholangiocarcinomaDue to its aggressiveness, this type of neoplasm will require surgery within a few weeks to avoid progression. In these patients, the risk of progression is equivalent to the risk of death in the near future, so the net benefit of surgery is expected to be high.36

If the patient presents jaundice, priority should be given to biliary drainage and/or portal embolization, if necessary, to prepare for hepatectomy.

Resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Table 3)37- •

Phases I–III: surgery is recommended, whenever possible, with little benefit from neoadjuvant treatments.

- •

Phases IV–V: neoadjuvant treatment based on the patient’s functional status and comorbidities.38

Neoadjuvant therapy is recommended regardless of the phase, if the functional status of the patient allows it.

Recommendations for the management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma according to phases of the pandemic.

| Pathology | Phase I | Phase II | Phase III | Phase IV–V | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hilar cholangiocarcinoma | Multidisciplinary committee new cases | Resectable | Consider surgery | Neoadjuvant | ||

| Locally advanced | Neoadjuvant | |||||

| Irresectable/metastatic | Palliative Tx +/− chemotherapy | |||||

| Completed neoadjuvant | Resectable | Surgery + adjuvant | Additional cycles of CT and local therapies | |||

Palliative treatment (biliary drainage) +/− chemotherapy treatment (Table 3).

Liver transplantation could be indicated in very selected cases.

Therapeutic recommendations for gallbladder cancer surgeryBecause there is limited evidence about the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for this type of cancer, surgical resection is recommended, if the phase of the pandemic allows and healthcare resources are available.

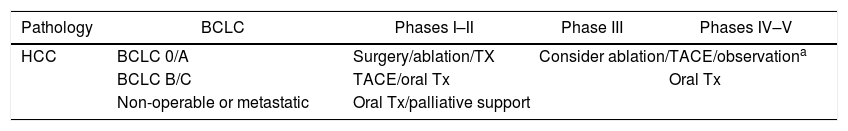

Therapeutic recommendations for liver cancer surgeryHepatocarcinoma (HCC) (Table 4)Following the BCLC39 classification and depending on the pandemic ‘alert’ phase of the hospital, the most appropriate treatment will be decided and agreed upon by the MC.

Recommendations for the management of hepatocarcinoma according to phases of the pandemic.

| Pathology | BCLC | Phases I–II | Phase III | Phases IV–V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCC | BCLC 0/A | Surgery/ablation/TX | Consider ablation/TACE/observationa | |

| BCLC B/C | TACE/oral Tx | Oral Tx | ||

| Non-operable or metastatic | Oral Tx/palliative support | |||

- •

Phases I–II: surgery/ablation/transplantation depending on the case.

- •

Phases III–V: delay definitive treatments like surgery or transplantation. Consider transarterial ablation/chemoembolization (TACE).

- •

Phases I–III: TACE/oral treatment (sorafenib/regorafenib/cabozantinib).

- •

Phases IV–V: oral treatments.

To ensure the protection of transplant recipients, universal microbiological screening of recipients and donors is recommended at the time of transplantation. Recipients with a high suspicion for infection will be ruled out after clinical screening or positive PCR.40 As the scenario of the pandemic changes over time, the guidelines to follow for liver transplants are determined by the information provided by the Spanish National Transplant Organization (NTO), which is updated periodically.

Resectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma- •

Phases I–II: surgery/ablation.

- •

Phases III–V: ablation and delay of definitive treatments.

In any phase: palliative support/oral treatment, individualized by patient

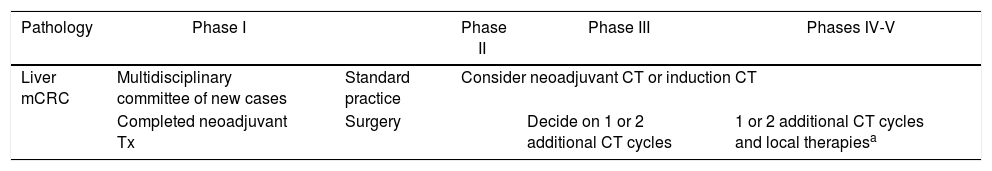

Liver metastasis of colorectal cancer (mCRC) (Table 5)In routine practice, the treatment of patients with liver metastases should be planned in MC due to the complexity of this pathology and the number of services involved in managing these patients. In this exceptional pandemic situation, patients must be even more carefully and individually evaluated.

Recommendations for management of liver metastasis of colorectal cancer according to phases of the pandemic.

| Pathology | Phase I | Phase II | Phase III | Phases IV-V | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver mCRC | Multidisciplinary committee of new cases | Standard practice | Consider neoadjuvant CT or induction CT | ||

| Completed neoadjuvant Tx | Surgery | Decide on 1 or 2 additional CT cycles | 1 or 2 additional CT cycles and local therapiesa | ||

The combination of systemic therapy and surgical resection has the longest survival in this type of pathology. Additionally, different local ablation methods (radiofrequency, microwave, radiotherapy, etc.) can be applied in selected cases.

There are different chemotherapy regimens associated with surgery, such as: neoadjuvant, induction or conversion, perioperative or adjuvant chemotherapy. Their use must always be agreed upon.41–44

In this pandemic situation, especially in alert scenarios II–V, the “surgery + adjuvant” scheme as the first option should be avoided or reconsidered because since healthcare resources will be affected (operating rooms, ventilators, etc.), in addition to the high risk of patient infection in the perioperative period. Therefore, chemotherapy and surgery schemes will be chosen.

In alert phase I, there will be no modifications when making decisions for chemotherapy and surgery schedules.

Neoadjuvant therapy completed in mCRCIn cases where the patient has completed neoadjuvant treatment and is awaiting surgery, there will be a window of 6–8 weeks in which surgery can be planned,7,45,46 without the patient losing the potential opportunity for cure. Thus, depending on the hospital’s level of alert, we will plan the surgery (Table 5) as agreed by the MC.

- •

Phases I–II: surgery.

- •

Phase III: assess with the oncology unit the possibility of adding one or 2 additional cycles, in order for the worst of the pandemic to have passed and the risk of infection for the patient to be minimized as much as possible.

- •

Phases IV–V: like in level III and/or local therapies in potentially curable patients.

At this moment of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, it is necessary to generate a plan for HBP cancer surgery that contemplates the different evolutionary scenarios where the hospital is located. The aim must be to protect patients and medical professionals from COVID-19 infection, without this being detrimental to the oncological treatment the patient requires.

In general, it is understood that HBP cancer surgery, due to its complexity, could necessitate modified planning, especially in phases III–V of the pandemic. In these cases, alternative bridging therapies are proposed while the situation lasts.

The results derived from the application of these recommendations may be assessed in future analyses by the HBP division of the AEC, which aim to evaluate the impact of the pandemic on HBP units and the application of the protocols.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Jose M. Balibrea (Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Universitat de Barcelona), Inés Rubio Pérez (Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid), Josep M. Badia (Hospital General de Granollers, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Barcelona), Esteban Martín-Antona (Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid), Estíbaliz Alvarez Peña (Hospital General de Granollers, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Barcelona), Alejandra García-Botella (Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid), Mario Alvarez Gallego (Hospital General de Granollers, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Barcelona), Elena Martín Pérez (Hospital Universitario de la Princesa, Madrid), Sagrario Martínez Cortijo (Hospital Fundación de Alcorcón, Madrid), Isabel Pascual Miguelañez (Hospital General de Granollers, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Barcelona), Lola Pérez Díaz (Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid), Jose Luis Ramos Rodriguez (Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Madrid), Eloy Espin Basany (Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona), Raquel Sánchez Santos (Complejo Hospitalario de Vigo, Vigo),Victoriano Soria Aledo (Hospital Morales Messeguer, Murcia), Xavier Guirao Garriga (Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí, Barcelona), Jose Manuel Aranda Nárvaez (Hospital Regional Universitario Carlos Haya, Málaga) and Salvador Morales-Conde (Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla).

Members of the Surgery-AEC-COVID-19 Work Group are listed in Appendix A.

Please cite this article as: García Botella A, Gómez Bravo MA, Di Martino M, Gastaca M, Martín-Pérez E, Sánchez Cabús S, et al. Recomendaciones de actuación en cirugía oncológica hepatobiliopancreática durante la pandemia COVID-19. Cir Esp. 2021;99:174–182.