The industry of vitamins and oral supplements moves millions of euros every year.1 In countries such as the United States, a typical sight in supermarkets and department stores is that of entire aisles devoted to this type of products. However, their tremendous popularity among the public contrasts with a notable scepticism among a large part of the scientific community. For example, in one of the most read editorials in the history of Annals of Internal Medicine, “Enough Is Enough: Stop Wasting Money on Vitamin and Mineral Supplements” by Guallar and co-authors, null or extremely modest benefits achieved from these supplements were described in the majority of clinical trials through 2013.2

More recently, an area of special interest in the last few years – and one to which considerable research resources have been devoted – has been ascertaining the effects on cardiovascular health and other endpoints of 2 very frequently used compounds, particularly for strengthening bone mineral density: vitamin D and calcium supplements. What do the studies tell us, in 2021, about the cardiovascular effects of each of them?

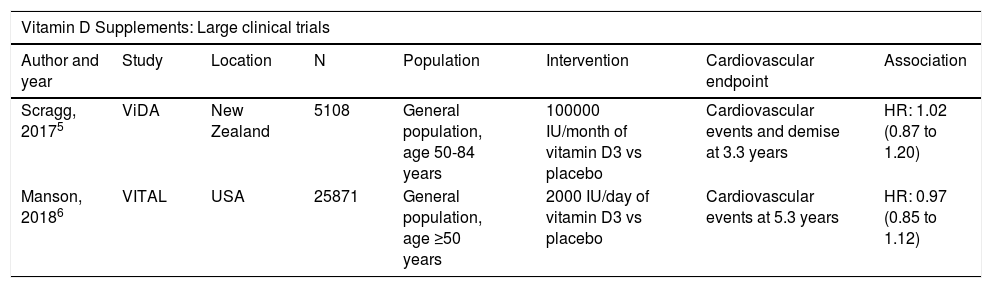

In the matter of vitamin D, several observational studies had reported associations between low levels of vitamin D in blood and an increase in cardiovascular events during follow-up. Paradigmatic examples of these studies include analysis using data from the United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES),3 the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study,4 and several meta-analyses of observational studies. This type of studies led to setting up clinical trials aimed at evaluating whether increasing vitamin D levels in blood by oral supplements could yield cardiovascular benefits, particularly to patients with conditions of deficiency/the lowest levels of vitamin D. Unfortunately, the findings from those studies have consistently been null from the cardiovascular point of view. That is the case of clinical trials such as the Vitamin D Assessment (ViDA)5 and the more recent Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL)6 study, among others (Table 1).

Summary of clinical trials on oral vitamin D and/or calcium supplements and cardiovascular events.

| Vitamin D Supplements: Large clinical trials | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author and year | Study | Location | N | Population | Intervention | Cardiovascular endpoint | Association |

| Scragg, 20175 | ViDA | New Zealand | 5108 | General population, age 50-84 years | 100000 IU/month of vitamin D3 vs placebo | Cardiovascular events and demise at 3.3 years | HR: 1.02 (0.87 to 1.20) |

| Manson, 20186 | VITAL | USA | 25871 | General population, age ≥50 years | 2000 IU/day of vitamin D3 vs placebo | Cardiovascular events at 5.3 years | HR: 0.97 (0.85 to 1.12) |

| Calcium Supplements: Meta-analysis of multiple small clinical trials | ||

|---|---|---|

| Author and year | Number of studies combined | Main findings |

| Jenkins, 201814 | Up to 179 trials of various supplements | The RR of each of the events (myocardial infarction, coronary events, ictus, cardiovascular events, demise) evaluated was >1.00, but without reaching statistical significance |

| Khan, 201915 | Up to 277 trials of various supplements | Possible increased risk of ictus when calcium supplements are combined with vitamin D supplements (RR: 1.17 [1.05 to 1.30]) |

| Yang, 202016 | 16 clinical trials and 26 observational cohorts (calcium) | Calcium from the diet would not increase cardiovascular risk, but calcium supplements might increase the risk of myocardial infarction (RR: 1.21 [1.08 a 1.35]) |

Abbreviations: HR = hazard ratio; IU = international units; RR = relative risk; USA = the United States of America; ViDA = Vitamin D Assessment study; VITAL = Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial.

What is the reason for this lack of agreement between experimental and observational studies? Discrepancies in findings between these 2 study designs are not uncommon in cardiovascular research. Testimony to this are such well known examples as hormone replacement therapy in women7 and the generalised use of antiarrhythmic drugs in patients after myocardial infarctions.8 Those are both examples in which the clinical trials did not confirm the promising signs of the observational studies, or even detected a significant increase in adverse events. In the case of vitamin D, the discordance might be explained by “residual confusion” in the observational studies: although researchers, in their multivariate analyses, include a great variety of potential confounding factors associated with both the exposition to study and the event of interest (for example, level of education or income), these analyses are often incapable of fully adjusting for all the factors that might cause a person to have higher levels of vitamin D than another, or better cardiovascular health. Such factors include healthier lifestyles, a better diet, better self-care or more exposure to outdoor activities (many of which frequently include physical exercise and socialisation), among others. Consequently, the associations reported were probably spurious. When the clinical trials just provided the participants with the substance (vitamin D in this case), without any other additional intervention (that is, without cardioprotective behaviours), the effect was negligible.

This experience brings us important lessons on several levels. With regard to vitamin D, these findings suggest that vitamin D levels in blood are, similarly to levels of cholesterol linked to high-density lipoproteins,9 a marker indicating heart-healthy lifestyles, rather than a causal factor or therapeutic target; and that these healthy lifestyles should be strengthened, not just the vitamin D levels in blood alone. In effect, people who eat a healthy diet with abundant sources of vitamin D (such as salmon), do sport outdoors and frequently socialise (all of which are characteristics of the Mediterranean lifestyle10) have better cardiovascular health, which occurs through multiple beneficial mechanisms. From the viewpoint of research and quality of scientific evidence, this discordance again underscores the need to prioritise clinical trials over observational studies when it comes to making Class I recommendations for the indication of pharmacological therapies in clinical practice guidelines. Finally, the lesson learned must also be reflected in the general press and digital media, which often give wide diffusion to observational studies on the possible health effects of vitamins, coffee or other highly popular substances, without sufficiently emphasising the potential limitations of such studies.11 This can add to health disinformation in the public, and must therefore be avoided as much as possible through more nuanced information.

At present, there is no evidence that justifies the use of oral vitamin D supplements to improve cardiovascular health. Such supplements have certain uses in paediatrics, and in bone health. However, it must be pointed out that the most recent clinical trials evaluating the usefulness of vitamin D supplements in preventing falls and fractures and improving bone mineral density have also produced negligible, or very modest, results. Consequently, prioritising healthy activities and foods that increase vitamin D levels also seems reasonable from the point of view of bone health.12

With regard to calcium supplements, the evidence as to their cardiovascular effects is more consistent among studies, although unfortunately it suggests negligible benefits and, in the case of a few studies, even a possible increase in risk of adverse events, such as myocardial infarctions or strokes (Table 1).13–16 Various pathophysiological mechanisms have been proposed, with the main ones being a possible state of hypercoagulability produced by transitory increases of calcaemia, and increases in blood pressure produced by vascular calcification.12 It is important to incorporate this information in conversations with patients in which this type of supplements are being considered for improving bone health. Again, ensuring a balanced diet with sufficient calcium supply, plus a lifestyle that includes activities that help to increase bone density, can provide important health benefits while minimising risks.

Mediterranean Europe is privileged to have a climate and access to foods that are heart-healthy, and their use has formed part of the local culture for thousands of years.10,17 Despite the current trend towards mimicry, with Anglo-Saxon standards and lifestyles, and the culture of immediacy in which we find ourselves immersed, the most recent studies show that the Mediterranean lifestyle is extremely healthy, and has to be nurtured and exported. Research on vitamins and minerals, particularly the studies about vitamin D supplements, also suggest that the benefits of the Mediterranean lifestyle cannot be compressed into a pill… or bought in department stores.

Conflicts of interestThe author declares that there are no conflicts of interest in relation with the content of this article.

Please cite this article as: Cainzos-Achirica M. Vitamina D, Calcio y Salud Cardiovascular: ¿Alimentos o Suplementos? —¿Cuál es la Evidencia en 2021? Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2021;33:70–72.