Migrant patients arriving in Spain often come from countries where there is no universal access to healthcare. Although the prevalence of arterial hypertension (HTN) is lower in West Africa than in Spain, there is a higher prevalence of masked HT due to the absence of health screening. Furthermore, patients with secondary hypertension may not be diagnosed. We present the case of a 36-year-old Senegalese man, with no known pathological history, resident for a year in Spain, who debuted with a hypertensive emergency. At the time of diagnosis, the patient had severe end-organ damage (hypertensive heart disease, hypertensive retinopathy). After the study, he was diagnosed with arterial hypertension secondary to malformation of the renal artery. After performing angioplasty, blood pressure normalized and, at 18 months, target organ damage had reduced. Migrants who arrive in our country must be incorporated into health screening systems to diagnose and treat possible unknown pathologies. In our case, the clue to secondary hypertension was the development of resistant hypertension with target organ damage in a young subject.

Los pacientes migrantes que llegan a España a menudo proceden de países donde no existe acceso universal a la sanidad. Aunque la prevalencia de hipertensión arterial (HTA) es menor en África occidental que en España, existe una mayor prevalencia de HTA enmascarada debido a la ausencia de cribados de salud. Esto también puede producir que no se diagnostiquen a los pacientes con HTA secundaria. Presentamos el caso de un varón senegalés de 36 años, sin antecedentes patológicos conocidos, residente desde hacía un año en España, que debutó con una emergencia hipertensiva. En el momento del diagnóstico, el paciente presentaba daño grave de órgano diana (cardiopatía hipertensiva, retinopatía hipertensiva). Tras el estudio, se le diagnosticó hipertensión arterial secundaria a malformación de la arteria renal. Después de realizar la angioplastia, la presión arterial se normalizó y, a los 18 meses, el daño a los órganos diana se había reducido.

There are several signs that should raise suspicion of secondary hypertension. These include hypertension in young patients (usually younger than 30 years old), severe hypertension or hypertension with early target organ damage.1 Although the criteria for screening for secondary hypertension are well established in developed countries, this situation is not the same in some developing countries. This situation is evident in our setting with patients migrating to Spain.

Renovascular disease is an important and potentially correctable cause of secondary hypertension. The frequency with which it occurs varies, but appears to account for less than 1% of cases of moderate and severe hypertension.2 Renal artery involvement may be secondary to atherosclerotic disease, vasculitis or vascular malformations, among other causes. Its importance lies in the fact that it is a potentially reversible cause of arterial hypertension.

Clinical case studyWe present the case of a 36-year-old Senegalese man, with no known pathological history. He emigrated to Spain at the age of 35 and currently lives in Baza, a small village in the province of Granada, and words in agriculture.

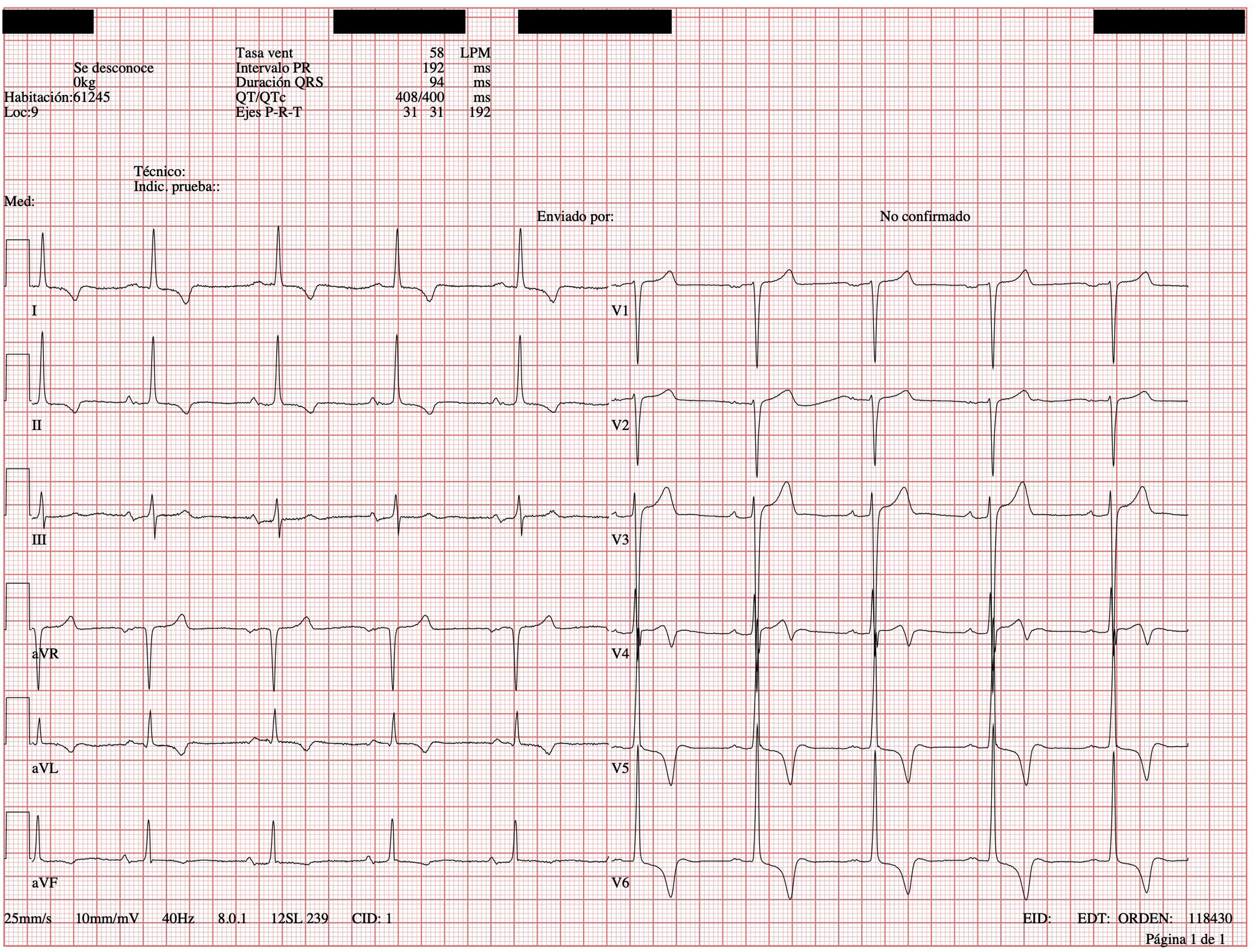

In January 2020 he went to the emergency department for hypertensive crisis (blood pressure 238/130mmHg). Physical examination revealed no differences in pulses or blood pressure between the two arms. Cardiac auscultation revealed a systolic murmur in mitral and aortic focus grade V/VI, which did not erase the second sound. There were no signs of heart failure or abdominal murmurs. The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed signs of ventricular hypertrophy (positive Sokolow-Lyon criteria and negative inferolateral T wave) (Fig. 1). The echocardiogram confirmed the ECG suspicion and diagnosed severe concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (septal thickness of 28mm at mid-septal level; inferior, lateral and anterior 24mm). In view of all these findings, an aetiological study of secondary arterial hypertension was performed.

This included thyroid hormones, plasma ACTH and cortisol and urine metanephrines, which were normal. Renin and aldosterone levels in blood were requested, with elevated values of both, suggestive of hyperaldosteronism (aldosterone 331pg/mL, normal between 38 and 150pg/mL, and renin 1989pg/mL, normal values between 1.7–23.9pg/mL).

Angio-CT showed a critical stenosis in the middle third of the left renal artery, with a vascular malformation in the form of a ball in the renal hilum extending caudally with numerous collaterals joining the vertebral and mesenteric arteries (Fig. 2) with delayed perfusion in the arterial and venous phase of the left kidney with respect to the contralateral kidney.

No atherosclerotic lesions were found on CT angiography. He also did not meet the criteria for Takayasu's arteritis or other types of vasculitis, nor had he presented any local trauma. For these reasons, it was suggested that the origin of the renal artery stenosis and vascular tangle was malformational in origin.

Renal angiography and renin/aldosterone selective venous sampling (SVS) was performed. This supported the angio-CT findings and demonstrated hypertensive behaviour of the left kidney. The left renal vein had a 3-fold higher renin concentration with respect to the common iliac and right renal veins (left vein: 265pg/mL; right vein 78pg/mL, reference values 3.58–36.62pg/mL).

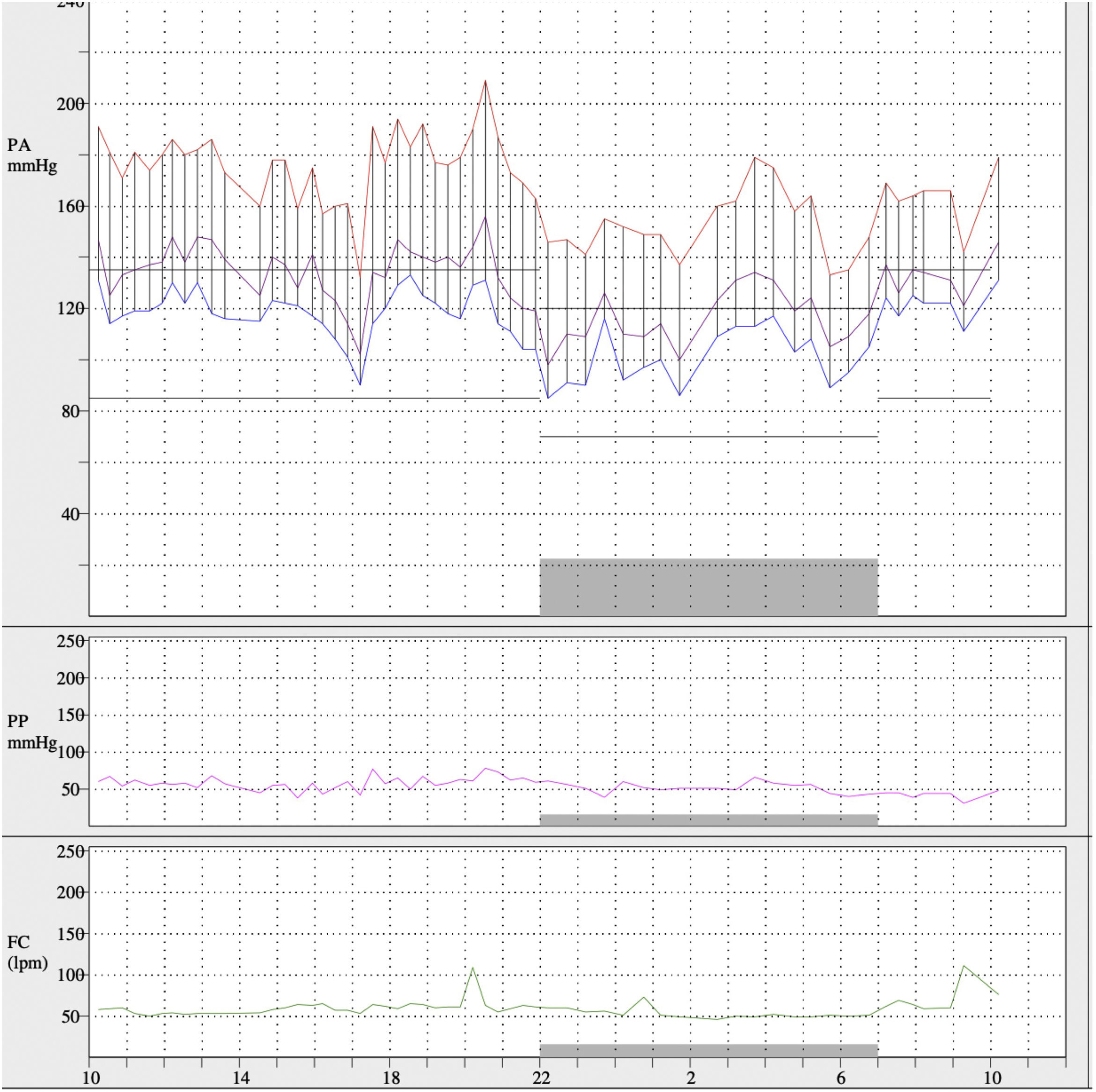

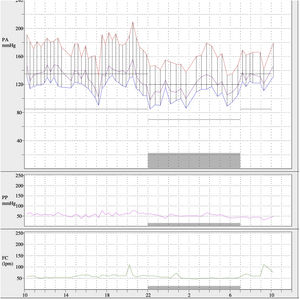

The presence of grade 3 hypertensive retinopathy and the findings on cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (severe circumferential hypertrophy of the left ventricle, predominantly in the middle and apical segments, as well as in the papillary muscles, with absence of late gadolinium enhancement) were confirmed. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) was performed to characterise the degree of arterial hypertension, showing mean 24h values of 168/113mmHg, daytime mean of 174/119mmHg and nighttime mean of 152/101mmHg (Fig. 3), with dipper pattern of blood pressure and with a percentage of systolic and diastolic readings above baseline values greater than 95%, despite daily treatment with labetalol 100mg 1 at breakfast, enalapril 5mg 1 tablet at breakfast and 1 tablet at dinner, manidipine 10mg 1 tablet at breakfast and 1 tablet at dinner and furosemide 40mg 1 tablet at breakfast. Higher doses of ACE inhibitors were not tolerated due to impaired renal function.

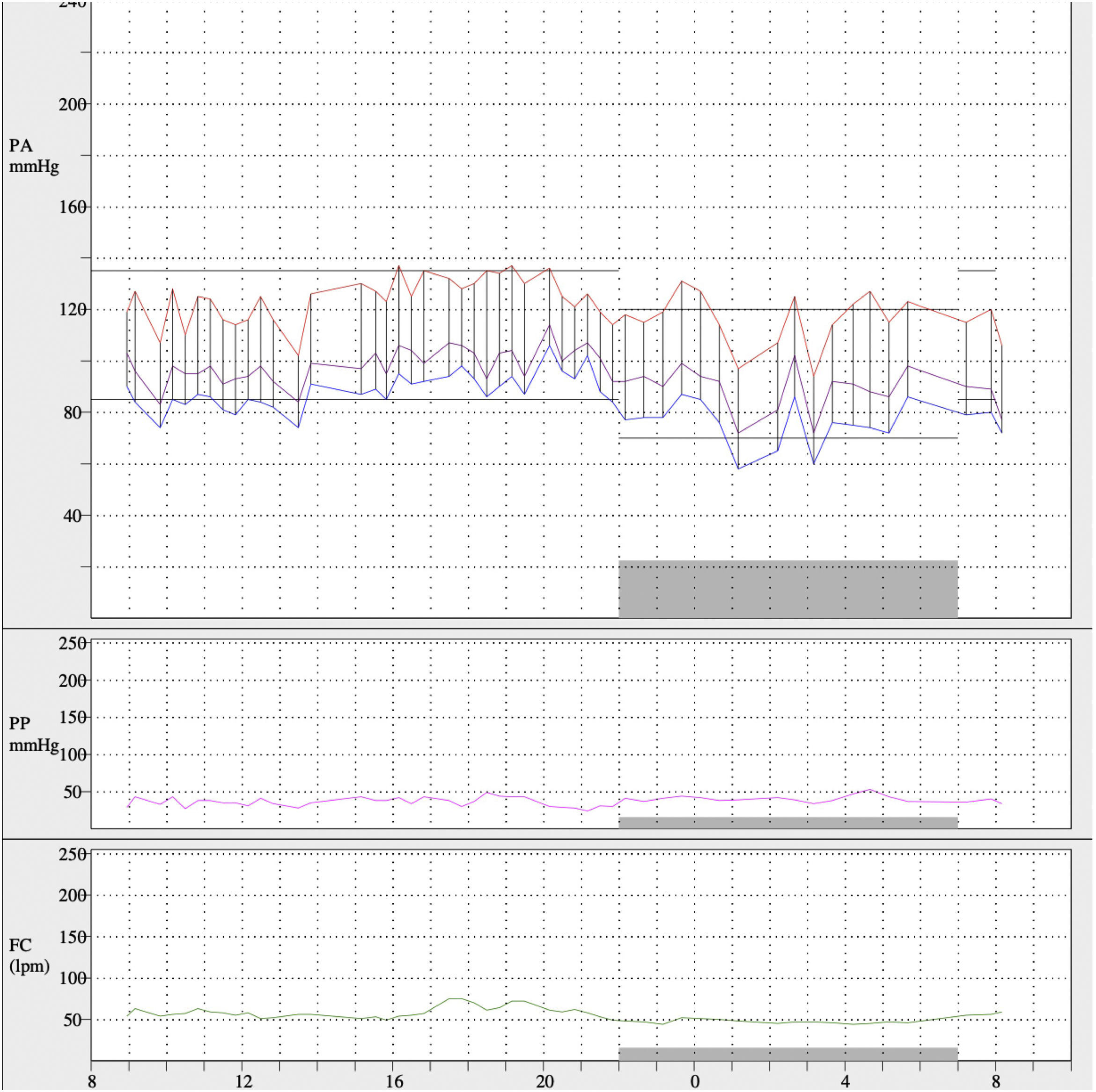

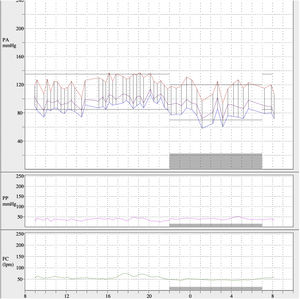

After left renal artery angioplasty, blood pressure values decreased and treatment was reduced to manidipine 10mg 1 tablet at breakfast and atenolol 50mg 1 tablet at dinner. On subsequent ABPM (Fig. 4) mean 24h blood pressure values were 121/84mmHg, daytime mean of 123/87mmHg and nighttime mean of 117/74mmHg. The blood pressure pattern was dipper and the percentage of systolic readings above baseline values less than 20%, with 65% of diastolic readings elevated. Eighteen months later, a transthoracic echocardiogram was performed and showed reduced ventricular hypertrophy, currently compatible with mild-moderate LVH (septal thickness 14mm; left ventricular posterior thickness 10mm).

DiscussionCardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death in Spain. Among the main causes are cardiovascular risk factors, which is why there are screening systems in place in primary care.3,4 Among them, arterial hypertension stands out, with an approximate frequency of 40% in Spain in people over 18 years of age. There are criteria under which the search for a secondary aetiology of hypertension is indicated. These include early onset (generally before the age of 30), severe or refractory hypertension, and analytical alterations (e.g., hypokalaemia).1

However, these circumstances are different in some developing African countries. According to a 1927 article in The Lancet, hypertension was an anecdotal condition in some African communities, with a prevalence of less than 5%.5 Today, however, cardiovascular diseases (including hypertension) represent a real public health problem, with increasing morbidity and mortality.6 There are also significant differences in the prevalence of hypertension between rural and urban populations, mainly due to changes in lifestyle and especially diet.7,8

In Senegal, an African country on the west coast of Africa with more than 13 million inhabitants, despite the existence of social security, there is no universal health coverage and no established basis for primary health care or screening programmes for chronic diseases such as hypertension. The estimated prevalence of hypertension in the area is less than 20%. This percentage, lower than that described in Spain,9 has been related mainly to dietary factors (such as lower salt consumption), although under-diagnosis bias must be considered due to lower access to the health system. Only 10%–20% of patients were found to have adequate blood pressure control.10

Hypertension has been reported to be more frequent and severe in blacks, although these data refer mainly to African-American patients, for multiple causes.11 Although there is less scientific evidence, it appears that sub-Saharan African populations also have more severe hypertension than white subjects, matched by age and sex. In a study published by the French National Academy of Medicine,8 patients from sub-Saharan Africa were found to have higher grade hypertension compared to age- and sex-matched controls. This could be due to increased obesity, although alterations in epithelial sodium channel functions and abnormalities in angiotensinogen and aldosterone synthase genes have also been suggested, although there is currently little evidence.11

No significant differences in the prevalence of secondary hypertension have been observed with respect to European populations, although there appears to be a higher frequency of primary hyperaldosteronism and lower renovascular hypertension.8 Renovascular hypertension has a frequency of less than 1% in people with mild or moderate hypertension, although this prevalence appears much higher in those with severe or refractory hypertension.2 The most common cause is atherosclerotic in origin, with vascular malformations or stenosis secondary to vasculitis being rare.

We know that migration is one of the greatest challenges facing society in the 21st century. Until now, the biggest health problems have been due to imported infectious pathology (e.g., malaria). However, the burden of cardiovascular diseases is increasing. Changes in diet and lifestyle in this population have led to an increase in the incidence of hypertension and diabetes. In addition, the lack of health checks in their countries of origin can lead to under-diagnosis of pathologies such as hypertension. In host countries, the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors is, in many cases, unknown in the migrant population due to less access to health resources.12,13 Therefore, in cases of prolonged evolution and poor control, these patients may develop hypertension-mediated target organ damage.

In the case in question, our patient had had high blood pressure for several years, as he had developed heart disease and hypertensive retinopathy, a condition of which he was unaware. For this reason, it had not been possible to diagnose the stenosis and malformation of the left renal artery that was causing the disease.

ConclusionsMigration is one of the major health challenges of the 21st century. So far, the focus has been mainly on imported infectious pathology, but we know that changing diets and lifestyles in developing countries are causing the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases to increase. In many of these countries, there is no universal access to healthcare, so they may go undiagnosed. For this reason, migrant patients arriving in their host countries should be included in health screening to avoid future health complications.

It is important to identify secondary and possibly reversible causes of hypertension. Renovascular pathology has a low frequency, with arterial malformations being a rare cause. In our case, after an in-depth study, the left kidney was found to have a pressor mechanism, characterised by increased renin and aldosterone. After correction of the renal artery stenosis, blood pressure values normalised.

FundingNone.

AuthorshipAll the authors contributed equally.

Conflict of interestsNone.