The objective of this study was to compare two four-strand techniques: the traditional Strickland and cruciate techniques.

METHODS:Thirty-eight Achilles tendons were removed from 19 rabbits and were assigned to two groups based on suture technique (Group 1, Strickland suture; Group 2, cruciate repair). The sutured tendons were subjected to constant progressive distraction using a universal testing machine (Kratos®). Based on data from the instrument, which were synchronized with the visualized gap at the suture site and at the time of suture rupture, the following data were obtained: maximum load to rupture, maximum deformation or gap, time elapsed until failure, and stiffness.

RESULTS:In the statistical analysis, the data were parametric and unpaired, and by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, the sample distribution was normal. By Student's t-test, there was no significant difference in any of the data: the cruciate repair sutures had slightly better mean stiffness, and the Strickland sutures had longer time-elapsed suture ruptures and higher average maximum deformation.

CONCLUSIONS:The cruciate and Strickland techniques for flexor tendon sutures have similar mechanical characteristics in vitro.

Flexor tendon lesions have always been a challenge for hand surgeons. However, due to advances in materials and suture techniques, the functional results of flexor tendon tenorraphies have improved (1,2).

New suture techniques are designed to provide sufficient strength during early rehabilitation without increasing the incidence of premature suture rupture or the work required for flexion (3). The strength of a flexor tendon repair is proportional to the number of suture strands that cross the repair site (1,4); however, this biomechanical advantage occurs at the expense of increased suture volume and decreased vascularity of the tendon, resulting in worse clinical outcomes, decreasing the incidence of adherence and increasing the requirement for secondary tenolysis (5).

Moreover, increasing the number of suture strands prolongs the time of repair and increases the difficulty; consequently, many surgeons prefer four-strand sutures (5,6). Studies of four-strand sutures have reported good strength, but unequal loads can occur when two knots are used because the knot itself is a weak point of the suture (7,8).

In recent articles on suture techniques, the cruciate technique has provided good tensile strength and has required greater force for failure and for the formation of gaps, without increasing the operative times (6,7,9)–(13). The cruciate repair suture was first described by McLarney et al. (10) and was considered the ideal technique by James W. Strickland, possessing the mechanical strength of a four-strand suture and technical simplicity of a two-strand suture (5,12). Although the cruciate technique provides better mechanical results in vitro, the Strickland technique remains one of the most widely used methods (14).

With regard to completing tendon repairs, the circumferential epitendinous suture increases the strength of the tendon suture by 10% to 50% and reduces the gap between the stumps of the tendons (1).

The objective of the present study was to compare different four-strand techniques, specifically the cruciate and Strickland sutures, both of which are reinforced by a continuous epitendinous suture in terms of the maximum load, maximum deformation, time elapsed until rupture and the stiffness of the sutures.

MATERIALS AND METHODSNineteen male and female New Zealand albino rabbits, between 3,500 g and 3,900 g, were acquired from the vivarium of the Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo, and were maintained in a laboratory for musculoskeletal research. The University of São Paulo Ethics Committee for Animal Resources approved this animal study.

The animals were euthanized with sodium thiopental at 75 mg/kg intraperitoneally, as per instructions from the Brazilian College of Animal Experimentation (COBEA, 2007). Both Achilles tendons from each rabbit were harvested, and the skin was sutured. The tendons were prepared immediately for testing. The animals were disposed of at the Center of Biological Material, University of São Paulo.

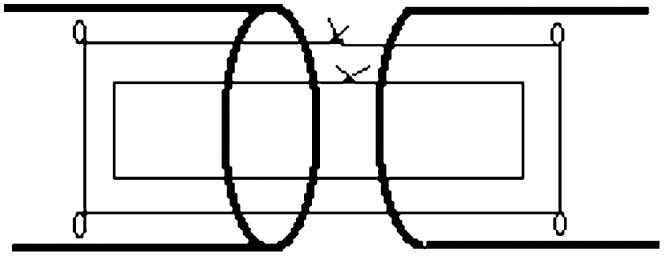

The tendons were divided into two groups, each consisting of 19 experiments. Each tendon was randomly repaired with one of the techniques: Group 1 received a Strickland suture (Figure 1); and Group 2 received a cruciate repair suture (Figure 2). Both groups were reinforced with a circumferential, epitendinous, simple running suture.

Each tendon was sectioned into two parts with a number 15 scalpel using a straight transverse cut and was sutured according to the randomization of surgical techniques with a 4–0 Nylon suture and with the core suture placed 7 mm from the cut edge of the tendon. The circumferential, epitendinous, simple running suture was held with 6–0 Nylon and a core suture purchase of 2 mm.

The average cross-sectional volume of the tendons in Group 1 was 15.87 mm2versus 15.65 mm2 in Group 2. The groups were homogeneous with regard to volume.

The repaired tendons were tested for failure by constant progressive distraction using a Kratos® universal testing machine, equipped with a load cell of 100 kgf and adjusted to a range of 10 kgf (accuracy of 10 gf). The tendon was fixed in the testing machine using two rectangular grasps with a trapezoidal profile; the distal end of the tendon was attached to a fixed section of the machine, and the proximal end was connected to the load cell in the movable part of the machine. The measurement system consisted of one mechanical linear actuator, and the load transducer connected to the proximal end of the Achilles tendon was connected to a computer, using the ADS2000 Lynx® data acquisition system. The force and displacement data measured by the system were registered.

To measure the gap between the cut edges of the tendon during mechanical testing, the tests were synchronized with a Sony DCR-HC26 digital camera. A two-point template with known distance was placed beside the tendon as a reference for the gap. Maximum deformation was calculated by setting the gap between the cut edges of the tendons at the time of suture rupture, measured in millimeters. The gap at the repair site was measured using a program that automatically identifies, calculates and records the gap in millimeters, based on the distance between points on the template as a reference.

To ensure synchronization between the data from the machine-based tests and measurements from the computer, a light-emitting diode (LED) was placed in the visual field of a digital camera that lit up at the same instant that the computer started to acquire data from the testing machine. This synchronization of equipment allowed us to calculate in seconds the maximum time elapsed until the moment of suture rupture.

Based on data from the testing machine, a computer program calculated the maximum load at the time of suture rupture for each test, and the stiffness of the suture was obtained by dividing the maximum load by the maximum gap in Newtons per millimeter.

EthicsThe University of São Paulo Ethics Committee for Animal Resources approved this animal study.

Statistical analysisIn our statistical analysis, the data were parametric and unpaired. The sample distribution was normal, as assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and the variance was homogeneous by Levene's test. Student's t-test was employed for quantitative variables. Descriptive and inferential analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 17.0 for Windows.

RESULTSGroup 1 underwent tenorrhaphy by the Strickland method, as follows: the average maximum deformation or gapping of the cut edges of the tendons at the time of suture rupture was 12.68 mm (median 13.05 mm, SD 2.86 mm). Group 2, which underwent cruciate tenorrhaphy, had an average value of 11.74 mm (median 11.51 mm, SD 3.16 mm).

In Group 1, the average time that elapsed until the moment of suture rupture was 44.9 seconds (median 46.0 seconds, SD 9.8 seconds), compared with 40.2 seconds in Group 2 (median 38.9 seconds, SD 10.4 seconds).

In Group 1, the average maximum force at the time of suture rupture was 34.83 N (median 35.15 N, SD 10.27 N) vs. 35.13 N in Group 2 (median 35.44 N, SD 12.85 N).

The mean stiffness in Group 1 was 4.31 N/mm (median 3.92 N/mm, SD 1.35 N/mm), compared with 5.16 N/mm in Group 2 (median 4.87 N/mm, SD 1.45 N/mm).

In our statistical analysis, by Student's t-test (2 × 2 table), none of the parameters were statistically significant. The median maximum force that was required for suture rupture and the stiffness of the sutures were greater with cruciate repair (p = 0.94). The Strickland technique resulted in higher median maximum deformation with a wider final gap (p = 0.36) and a longer time elapsing until the moment of suture rupture (p = 0.15). Boxplots for these values were generated for the samples (Figures 3 and 4).

DISCUSSIONVarious tendon sutures have been compared with regard to their techniques, materials and use of epitendinous sutures. The ideal suture, according to Strickland (1), must: 1) be easy to perform; 2) be reliable; 3) result in homogeneous coaptation of the cut edges of the tendon; 4) create a lower gap in the suture zone; 5) provide less interference with tendon vascularity; and 6) provide sufficient strength to facilitate early rehabilitation.

The ideal suture can be achieved through techniques with a higher number of strands that cross the repair site, which, however, can also lead to increased technical difficulty and more time to perform (13). Moreover, tendons can be injured, with impairments to vascularization, using techniques that use six or more strands (1). The most widely used techniques are the four- and six-strand methods, which are considered superior to two-strand techniques (6,15).

The epitendinous suture increases the resistance of the tendon by 10% to 50% and reduces the gap at the repair site of the tendon. In the present study, epitendinous suturing was performed in both groups, but its presence in mechanical tests hindered the visualization and evaluation of gap formation at the repair site, thereby generating a homogeneous suture and increasing early suture resistance (1).

Savage (16) suggested that the ideal suture should withstand a force at the repair site that is five times greater than the force necessary to actively move the tendon without resistance. Initial studies of the cruciate technique (17) demonstrated that it is capable of supporting strength beyond the physiological requirement for active movement.

In our study, both sutures attained a strength that exceeded 30 N, sufficient to allow for active rehabilitation protocols, per Viinikiainen et al. (18,19). Because the tests were performed in rabbit tendons in vitro, it was not possible to compare the values of human flexor tendons in the suture tests; these values should approximate one another, although rabbit tendons have less mechanical resistance and smaller diameters.

Another limitation of this experimental study, similar to all in vitro studies, was the inability to study the effects of postoperative edema, tendon resistance and gap formation during active movement (17).

In this study, we also observed that the cruciate repair suture technique was easier to perform and had a lower volume at the repair site, with one suture knot, and a more homogeneous suture, which was consistent with the literature (6,7,10). During the tests, the cruciate repair suture formed a more homogeneous graph of deformation versus resistance, whereas the Strickland suture had one of its knots rupture and rapidly lose resistance, which might be attributed to the difficulty in creating equal tension between the Kessler suture and the U suture of the Strickland technique.

Four-strand cruciate suture techniques are easier to perform, provide less interference with tendon gliding and are sufficiently strong for an early active motion protocol (15,17); in our study, however, there were no significant differences between the Strickland and cruciate repair techniques regarding the maximum load required to rupture the suture, the maximum deformation at failure or the stiffness, which can be explained by the number of tests that were performed with each technique. The cruciate repair suture also had a lower tendency toward gap formation, which will be evaluated in future studies.

Croog et al. (6) studied various configurations of the cruciate repair suture and noted that the cross lock increased the overall resistance, as well as the resistance to gap formation (20). Based on our observation that the simple cruciate repair suture had similar resistance compared with the Strickland technique, we recommend using the cross lock cruciate repair suture, which improves suture strength without significantly increasing the technical difficulty.

Hand surgeons should aim to simplify tendon sutures and to maintain the suture strength without increasing the technical difficulty (21). Thus, we advocate the cruciate repair suture technique, which yielded results comparable to the Strickland method in our study, in addition to its reported advantages. The technical benefits of the cruciate repair suture under clinical conditions could generate a lower coefficient of friction, thereby reducing failures, which we did not address in our experiments (5,6,7,9,10).

The cruciate repair suture is similar to the Strickland method with regard to the maximum load and the stiffness to suture rupture. Further studies should be conducted to investigate the clinical results of these techniques.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThe authors thank Cesar A. M. Pereira for helping to perform the mechanical tests in the Laboratory of Musculoskeletal Research (University of São Paulo).

Iamaguchi RB contributed to the study design, data collection, assessment of the results, statistical analyses and manuscript preparation. Villani W and Santos GB contributed to the data collection. Rezende MR, Wei TH and Cho AB were responsible for the critical revision. Mattar R supervised the study.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.