Phlegmonous gastritis or suppurative gastritis is a rare condition characterized by a purulent inflammatory process involving the gastric wall that can occur in a diffuse, localized, or mixed form. The most common type, the diffuse form, is characterized by initial involvement of the gastric submucosa with posterior extension to all layers of the gastric wall, resulting in extensive gangrene of the stomach. Although the exact pathogenesis of phlegmonous gastritis is unknown, it is likely caused by a bacterial infection of the stomach wall seeded either directly by invasion through a breach in the gastric mucosa or secondary to hematogenous spread from a distant source of infection.6,9,10 Predisposing conditions associated with suppurative gastritis include alcoholism, diabetes, ingestion of a foreign body, gastric surgery, endoscopic polypectomy, ingestion of corrosive agents, gastritis, chronic peptic ulcers, gastric carcinoma, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.5,9,12,17–19 Until recently, the recommended therapy for an intramural gastric abscess was surgical drainage in combination with antibiotics. However, technical advances now allow both radiologic and endoscopic intervention. In this case report, we describe an intramural gastric abscess that was successfully treated with antibiotics and endoscopic drainage.

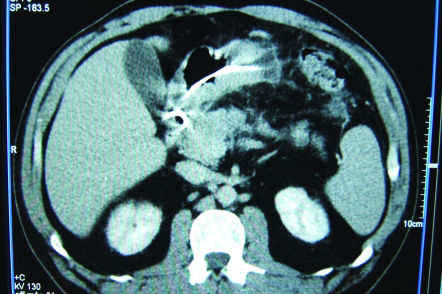

Case ReportA 48-year-old man presented to the hospital with a 5-day history of fever and dull epigastric pain radiating to the back and left upper quadrant of the abdomen. His medical history included a large hiatal hernia and erosive gastritis, both documented by a recent upper endoscopy. He did not have a history of alcohol abuse or pancreatitis and was currently taking omeprazole for gastroesophageal reflux. On admission, he was febrile and a tender, 8-cm mass was palpable in his upper epigastrium. His laboratory tests were all within normal limits, with the exception of a white blood cell count of 12 × 103/mm3 (normal: 3,5 a 10,5 × 103 /mm3). An abdominal ultrasound was performed, and it showed a thickened parietal gastric wall (1.3 cm) at the gastric antrum in the great bend, and pylorus. Intravenous antibiotics (ampicillin and sulbactam) were initiated empirically. His fever remitted within three days, but his pain persisted. A computed tomography scan was performed that revealed an abscess, 10 cm in length, within the gastric wall and adjacent to the large curvature, near the gastric antrum (Figures 1 and 2). Endoscopic ultrasound showed a well-circumscribed intramural mass of mixed echogenicity in the gastric wall, and the presence of internal fluid and debris confirmed the presence of an abscess (Figure 3). Endoscopic drainage was performed with a needle knife, and abundant purulent discharge was removed. A pigtail catheter was put in place for drainage (Figure 4). Bacterioscopy of the drained material revealed gram-positive cocci present in pairs and chains. Candida albicans was the organism cultured. The patient was discharged from the hospital, and an endoscopic ultrasound performed one month after the drainage demonstrated no residual fluid collection. At that time, the pigtail catheter was removed, and the patient continues to remain asymptomatic.

DiscussionA localized abscess of the gastric wall is one variety of phlegmonous or suppurative gastritis,9 a purulent inflammatory process involving the gastric wall that can occur in diffuse, localized, and mixed forms. The localized form accounts for 5 to 15% of all cases.1–4 The more common diffuse form is characterized by involvement of the gastric submucosa, with posterior extension into all layers of the gastric wall, and results in extensive gangrene of the stomach.1,9 Microscopically, the stomach exhibits marked submucosal thickening, with flattening of the overlying mucosa and loss of the normal folds, an appearance that mimics Gastro intestinal stromal tumors.9

The exact pathogenesis of phlegmonous gastritis is unknown. It is probably caused by bacterial infection of the gastric wall by direct invasion through a breach in the gastric mucosa or secondary to hematogenous spread from a distant infectious source.6,9,10Streptococci are the most common bacteria isolated in cultures from gastric abscesses (75% of cases). 1Other pathogens that have been isolated include Staphylococci, E. coli, Haemofilus influenzae, Proteus species, Clostridium welchii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Bacillus subtilis.6,11–16 In this case, Candida albicans was the organism cultured.

Predisposing conditions associated with suppurative gastritis include alcoholism, diabetes, ingestion of a foreign body, gastric surgery, endoscopic polypectomy, ingestion of corrosive agents, gastritis, chronic peptic ulcers, gastric carcinoma, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.5,9,12,17–19 The condition affects men more often than women, in a ratio of 3∶1, and the average age of patients ranges from 30 to 60 years old.9,12,14,20 In this case, the patient was a 48-year-old man who suffered from gastritis, but without other predisposing conditions.

To our knowledge, only 19 cases of gastric abscesses have been reported.5 The majority of patients present with abdominal pain,1 but other symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, and, rarely, fever.1 Two specific but seldom present clinical signs are Deininger's sign (decreased pain when changing from a supine to a sitting position)6 and vomiting of frank pus.7

Until recently, the recommended therapy for an intramural gastric abscess was surgical drainage in combination with antibiotics. However, technical advances now allow both radiologic and endoscopic intervention. Endoscopic drainage with or without antibiotics has been shown to be effective.1,5,19 From the 19 cases of gastric abscess that have been reported, 12 underwent surgery, 4 were drained endoscopically, 2 were drained percutaneously, and 1 patient took antibiotics alone without drainage. The surgical approach in the majority of cases is probably due to the fact that a gastric abscess is seldom diagnosed preoperatively and is often misdiagnosed. In prior studies, all patients were successfully treated, with the exception of the death of the one patient treated merely with antibiotics.1,21

In our case, the abscess was treated with antibiotics and endoscopic drainage of the purulent fluid through the gastric lumen. A pigtail catheter was left in place for one month to allow for additional drainage of pus.

This case highlights many of the salient points regarding the presentation, evaluation and management of intramural gastric abscesses. The initial presentation and CT findings were suggestive of a gastric abscess, and an endoscopic ultrasound with drainage of the purulent secretion by conventional endoscopy confirmed the diagnosis and permitted treatment of the condition.