Severe cognitive impairment follows thyroid hormone deficiency during the neonatal period. The role of nitric oxide (NO) in learning and memory has been widely investigated.

METHODS:This study aimed to investigate the effect of hypothyroidism during neonatal and juvenile periods on NO metabolites in the hippocampi of rats and on learning and memory. Animals were divided into two groups and treated for 60 days from the first day of lactation. The control group received regular water, whereas animals in a separate group were given water supplemented with 0.03% methimazole to induce hypothyroidism. Male offspring were selected and tested in the Morris water maze. Samples of blood were collected to measure the metabolites of NO, NO2, NO3 and thyroxine. The animals were then sacrificed, and their hippocampi were removed to measure the tissue concentrations of NO2 and NO3.

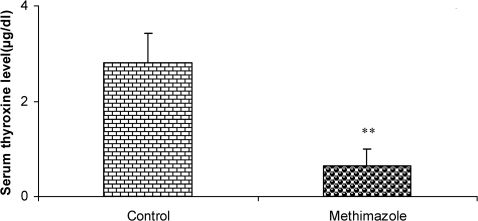

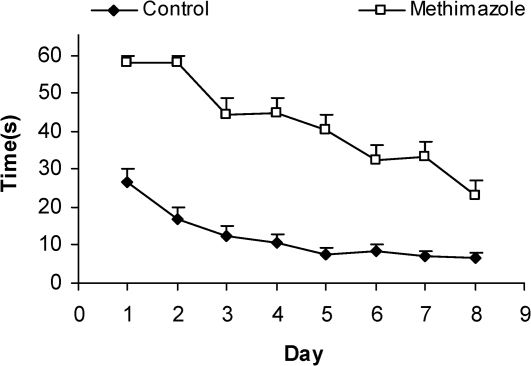

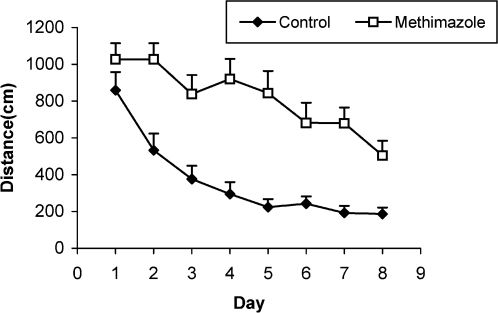

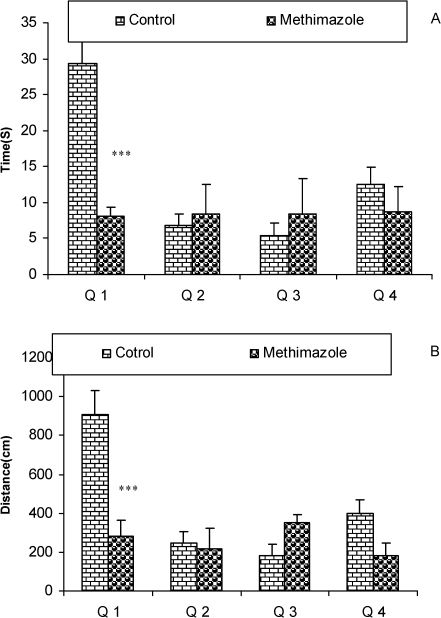

DISCUSSION:Compared to the control group's offspring, serum thyroxine levels in the methimazole group's offspring were significantly lower (P<0.01). In addition, the swim distance and time latency were significantly higher in the methimazole group (P<0.001), and the time spent by this group in the target quadrant (Q1) during the probe trial was significantly lower (P<0.001). There was no significant difference in the plasma levels of NO metabolites between the two groups; however, significantly higher NO metabolite levels in the hippocampi of the methimazole group were observed compared to controls (P<0.05).

CONCLUSION:These results suggest that the increased NO level in the hippocampus may play a role in the learning and memory deficits observed in childhood hypothyroidism; however, the precise underlying mechanism(s) remains to be elucidated.

Many studies have shown a significant role for thyroid hormones in the development and maturation of the mammalian central nervous system.1,2 These hormones regulate axonal and dendritic growth and synapse formation.3 Growth retardation and severe cognitive impairment are known complications following thyroid hormone deficiency in the prenatal and neonatal periods.4 It has been shown that hypothyroidism is associated with changes in gene expression in both the central and peripheral nervous system.5 The inability to produce long-term potentiation (LTP) in the rat hippocampus and impaired learning and memory in both rats and humans are among the functional consequences of hypothyroidism.6 Other studies have suggested that hypothyroidism affects behavioral conditions and is accompanied by emotional symptoms, including lethargy and dysphoria.7-11 The results of other studies have shown that several cognitive deficits, including attention and memory processing deficits, general intelligence and visual-spatial skills, are induced by hypothyroidism.9,10 Hypothyroidism has a lesser effect on auditory attention, motor skills, language and set-shifting.7,10,12 In addition, there is evidence indicating that even subclinical hypothyroidism is associated with depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment.13

Nitric oxide (NO), a free radical gas, is known to play critical roles in biologic systems;14 It acts like a diffusible intercellular signaling molecule in the brain and spinal cord.15 NO synthase (NOS) is the enzyme that produces NO from l-arginine. NO can act as an important mediator in synaptic plasticity, LTP and the consolidation of LTP.16-18 In addition, there are reports that suggest a relationship between NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate)receptors and the NO system in learning and memory.19,20 Several studies have shown that NOS inhibitors impair the consolidation of memory21,22 and block the induction of LTP.21-24 There is, however, some evidence showing that l-arginine, an NO precursor, improves memory formation and reverses the effect of NOS inhibition.25 There are also reports indicating that NO donors activate both LTP and long-term depression.23,26 These results suggest the involvement of NO in learning and memory processes.

The relationship between thyroid hormones and the NO system has been well documented.23,26-28 There is evidence that thyroid hormones are involved in regulating NO synthase gene expression in the brain. Considering the aforementioned findings, this study aimed to investigate the effect of hypothyroidism induced during the neonatal and juvenile periods on learning and memory of offspring and on NO metabolite concentrations in the hippocampus.

MATERIALS AND METHODSAnimals and treatmentsTwenty pregnant female Wistar rats (8 weeks old and weighing 200 ± 20 g) were kept in separate cages at 22 ± 2 °C in a room with a 12 h light/dark cycle (light on at 7:00 am). Offspring were randomly divided into two groups and treated according to the experimental protocol from the first day after birth through the first two months of life. Rats in the control group received normal drinking water, whereas the second group received the same drinking water supplemented with 0.03% methimazole (Sigma, USA) to induce hypothyroidism.29 After 60 days, seven male offspring of each group were randomly selected and tested in the Morris water maze (MWM).

In the methimazole group, hypothyroidism was confirmed by testing serum thyroxine concentration levels using the radioimmunoassay method (Daisource, T4- RIA - CT).

Animal handling and all related procedures were carried out in accordance with the rules set by the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences Ethical Committee.

Morris water maze apparatus and proceduresA circular black pool (136 cm diameter, 60 cm high, 30 cm deep) was filled with water (20–24 °C). A circular platform (10 cm diameter, 28 cm high) was placed within the pool and was submerged approximately 2 cm below the surface of the water in the center of the southwest quadrant. Outside the maze, fixed visual cues were present at various locations around the room (i.e., a computer, hardware and posters). An infrared camera was mounted above the center of the maze and an infrared LED was attached to each rat for motion tracking. Before each experiment, each rat was handled daily for 3 days and habituated to the water maze for 30 sec without a platform. The animals performed four trials on each of the eight consecutive days, and each trial began with the rat being placed in the pool and released facing the side wall at one of four positions (the boundaries of the four quadrants, labeled North (N), East (E), South (S) and West (W). Release positions were randomly predetermined. For each trial, the rat was allowed to swim until it found and remained on the platform for 15 seconds. If 60 seconds had passed and the animal had not found the platform, it was guided to the platform by the experimenter and allowed to stay on the platform for 15 sec. The rat was then removed from the pool, dried and placed in its holding bin for 5 min. The time latency to reach the platform and the length of the swimming path were recorded by a video tracking system.29,32-34 On the ninth day, the platform was removed, and the animals were allowed to swim for 60 s. The time spent in the target quadrant (Q1) and the traveled path were compared between groups. All measurements were performed during the first half of the light cycle.

Biochemical assessmentAfter the last session of the MWM test, blood samples were taken from all rats to determine hypothyroidism status and to measure the NO metabolites NO2 and NO3 (Griess reagent method). The animals were then sacrificed, and hippocampi were removed and submitted to NO metabolite measurements in the tissue. The Griess reaction was adapted to assay nitrates as previously described.35 Briefly, standard curves for nitrates (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) were prepared, and samples (50 µl plasma and 100 µl tissue suspension) were added to the Griess reagent. The proteins were subsequently precipitated by the addition of 50 µl of 10% trichloroacetic acid (Sigma). The contents were then vortex-mixed and centrifuged, and the supernatants were transferred to a 96-well flat-bottomed microplate. Absorbance was read at 520 nm using a microplate reader, and final values were calculated from standard calibration plots.36

Statistical analysisAll data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Swim time latency and the length of the traveled path over the eight training days were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance ANOVA. The time spent in the target quadrant (Q1) and the length of the swimming path in this quadrant was compared using unpaired t-tests. Comparison of serum thyroxin levels and plasma levels of NO metabolites was carried out using unpaired t-tests. The criterion for statistical significance was P<0.05.

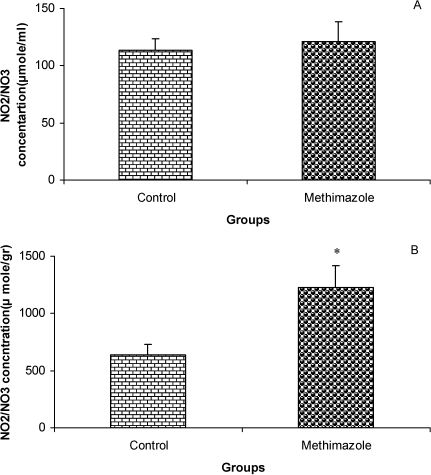

RESULTSThe serum thyroxine concentration in methimazole-treated animals was significantly lower compared to that of control animals (P<0.01; Fig. 1). In addition, the time latency and the length of the swimming path over the eight training days were significantly higher in offspring of the methimazole group (P<0.001; Figs. 2 and 3, respectively). In the probe trial, the time spent in the target quadrant (Q1) by the offspring of the methimazole group was significantly lower compared to controls (P<0.001; Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the length of the traveled path in Q1 by animals in the methimazole group was shorter than for those in the control group (P<0.001; Fig. 4B). There were no significant differences in the time spent or the length of the swim path in the other quadrants between the two groups. In addition, there were no significant differences between the plasma concentrations of NO2 or NO3; however, the concentration of NO metabolites in the hippocampi of the methimazole group offspring was higher than that of the control animals (P<0.05; Figs. 5A and 5B, respectively).

Serum thyroxine concentrations (µg/dl) in offspring of methimazole and control groups. The animals in the control group received regular drinking water, whereas the methimazole group received the water supplemented with 0.03% methimazole. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 7 in each group). ∗∗P<0.01 compared to controls.

Comparison of swim time latency (sec) to find the platform between offspring of the methimazole and control groups. The latency was significantly higher in offspring of rats in the methimazole group compared to controls (P<0.001). Data are shown as mean ± SEM of seven animals per group.

Comparison of the length of the swimming path (cm) between methimazole-treated animals and controls using a repeated measure ANOVA. The length of the swimming path in the offspring of the methimazole group was significantly higher than that of controls (P<0.001). Data are shown as mean ± SEM of seven animals per group.

The results of the time (sec) spent (4A) and the length of the swimming path (cm) (4B) in each quadrant during the probe trial on day 9 (24 h after the last secession of learning). Data are shown as mean ± SEM of seven animals per group. The platform was removed, and the time spent and the length of the swim path in the target quadrant (Q1) was compared between the groups. The time spent and the length of the swim path in Q1 by the offspring of the methimazole group was significantly lower compared to controls. ∗∗∗P<0.001 compared to controls.

Comparison of plasma NO metabolite levels (A) and the concentrations of these metabolites in hippocampal tissue (B) between offspring of the methimazole and control groups. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of seven animals per group. There were no significant differences between the plasma concentrations of NO2 or NO3; however, the concentration of NO metabolites in the hippocampi of the methimazole group offspring was higher than that of the control animals. ∗P<0.05 compared to controls.

Neonatal hypothyroidism has been clearly shown to be related to cognitive dysfunction.9-11,37,38 For example, studies in humans have shown that a temporal deficiency in thyroid hormones during developmental periods impairs cognitive functions such as attention, learning and memory.39 Experimental hypothyroidism in developing rats has also been shown to result in impaired learning and memory.40,41 In this study we induced hypothyroidism in rats, resulting in impaired learning and memory during the neonatal and juvenile periods.

Hypothyroidism impairs hippocampal-dependent learning and short- and long-term memory.42,43 In addition, hypothyroidism impairs early and late phases of LTP.44 The exact mechanisms underlying the induced deficits in memory and LTP have not been elucidated. Many studies have demonstrated that cognitive dysfunction in hypothyroidism is likely due to abnormal brain development, diminished inter-neuronal connectivity and, in particular, impaired synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus.45 It has been shown that maturation and function of the hippocampus are dependent on thyroid hormones.43 Transient hypothyroidism has even been shown to impair synaptic transmission and plasticity in the adult hippocampus.46,47 It has also been reported that impairment of LTP and memory due to hypothyroidism correlates with changes in c-jun and c-fos protein expression and extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERKs) levels in the hippocampus during crucial periods of brain development.48,49 Changes in the expression of other proteins such as synapsin I, synaptotagmin I, and syntaxin may also be involved in hypothyroidism-induced memory deficits.50 It has also been suggested that thyroid hormone deficiency results in changes in brain regions such as the dorsal hippocampal-mPFC pathway and changes in the glutamate release, which can lead to cognitive disturbances.51-53 Moreover, hypothyroidism has been shown to induce oxidative stress in the hippocampus.54

The relationship between oxidative stress, neuronal damage and cognitive dysfunction has been well documented.55-58 In addition, it is well known that neonatal hypothyroidism is accompanied by a delay in myelinogenesis and a decrease in the number of myelinated axons.59,60 In the present study, we have shown that a deficiency of thyroid hormones during lactation and in the neonatal period could impair learning of offspring in the MWM test. The animals in the hypothyroid group had significantly higher time latency to find the platform during every day of training (Fig. 2), indicating a deleterious effect of the lack of thyroid hormones on spatial learning processes. The results presented here also confirm that methimazole-induced hypothyroidism during the neonatal and juvenile periods impairs spatial memory given that the animals in the hypothyroid group spent less time in the target quadrant compared to the control group when tested on the ninth day (probe trial; Fig. 4). The results of the present study are consistent with findings from our previous study, in which we found an impairment in the MWM in adult rats with methimazole-induced hypothyroidism over a 180-day period.29 It has also been reported that treatment of thyroidectomized adult rats with thyroxine improved radial arm water maze tasks and LTP in the CA1 area of the hippocampus.61 These researchers showed that cyclic-AMP response element binding protein (CREB) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) may contribute to the impairment of hippocampal-dependent learning and memory; however, the authors suggested that calcium-calmodulin-dependent NOS and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) may not have roles in this process.61

The free radical gas NO has been associated with different forms of learning and memory and in several forms of synaptic plasticity thought to be involved in memory formation. This association has been widely confirmed via pharmacological studies, which have utilized a variety of substances and methods to inhibit NO synthase. Results from knockout studies in mice have revealed that mice deficient in eNOS and nNOS expression exhibit impaired LTP.20,61-65 It has also been reported that nitrergic neurons, the neurons that produce NO, increase in number after spatial learning in rats, which can be interpreted as upregulation induced by behavioral training.63 This evidence implies that NO participates in the memory process.63 In contrast to these results, which indicate a positive role for NO in learning and memory, it has been shown that inhibition of NOS does not prevent the induction of LTP or impair spatial memory. Thus, these findings suggest that NO does not play an important role in memory and learning.66 Here, we have examined the relationship between NO and hypothyroidism. We found that both hypothyroidism and impaired MWM performance were present in the methimazole group.

We also found a significant increase in hippocampal NO metabolites in the methimazole-treated group. The association between hypothyroidism and increased NO levels in the brain has been previously investigated. One study indicated that maternal thyroid hormone deficiency during the early gestational period resulted in a significant elevation in neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) expression with associated neuronal death in the embryonic rat neocortex.67 It has also been shown that nNOS acts as a negative regulator of neurogenesis.67-69 The inhibitory effect of NO on neurogenesis may be due to a reduction in the proliferative potential of neural precursor cells70 or a defect in the survival of newly generated neurons after differentiation.71 There is evidence showing that thyroid hormone deficiency increases cell death.67 The relationship between nNOS and poor survival of neurons and thyroid hormone deprivation has also been suggested.67 It has been shown that even a moderate and transient decrease in maternal thyroxine significantly increases nNOS expression, which is reversible by hormone replacement.67,72 In contrast, another report showed that propylthiouracil (PTU)-treated animals exhibited reduced NOS activity that could be rescued by T4 administration.72

It has also been shown that hypothyroidism changes the pattern of NOS activity in a tissue-dependent manner. NOS activity was significantly increased in both the right and left ventricles, but it was significantly reduced in the aorta, whereas in the vena cava, renal cortex and medulla, the enzyme activity was non-significantly higher compared to controls.73 The results of the present study also showed no difference in NO metabolites between the hypothyroid group and controls in peripheral blood samples. It might be suggested that an increase in NO in the hippocampus is due to stimulatory effects of thyroid hormone deprivation on nNOS activity. Although some studies have suggested NO to be a neurotransmitter that plays an important role in enhancing memory, others have claimed that its excess in the hippocampus may result in memory deficits.74 NO has been shown to have bidirectional effects. Under normal physiological conditions, it acts as an important neuronal messenger; however, when NO increases to high concentrations, it has a toxic effect that can lead to neuronal death.75-77 A common example of the toxic effect of NO in the CNS is due to glutamate neurotransmission and the activation N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, which leads to significant increases in intracellular calcium, followed by stimulation of neuronal NOS.77,78

Finally, other findings have suggested selective enhancement of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation in the amygdala and hippocampus of rats after three weeks of treatment with methimazole. These authors showed a significant increase in NOS activity,54 suggesting a correlation between increased NOS activity and elevated oxidative stress. It may therefore be suggested that increased NO production in the hippocampus during hypothyroidism acts as an oxidative stressor, which may explain the deficits in learning and memory observed here.

CONCLUSIONSIn this study, we found that hypothyroidism induced during the neonatal and juvenile periods resulted in impaired learning and memory of rats tested in the Morris water maze. In addition, we found an increase in NO metabolites in the hippocampus, suggesting that the impairment of memory in hypothyroidism may be due to increases in NOS and NO.

We would like to thank the Vice Chancellor of Research of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences for financial support.