To describe the normal and variant anatomy of the coronary artery ostia in Indian subjects.

INTRODUCTION:Anomalous coronary origins may cause potentially dangerous symptoms, and even sudden death during strenuous activity. A cadaveric study in an unsuspected population provides a basis for understanding the normal variants, which may facilitate determination of the prevalence of anomalies and evaluation of the value of screening for such anomalies.

METHODS:One hundred and five heart specimens were dissected. The number of ostia and their positions within the respective sinuses were observed. Vertical and circumferential deviations of the ostia were observed. The heights of the cusps and the ostia from the bottom of the sinus were measured.

RESULTS:No openings were present in the pulmonary artery or the non-coronary sinus. The number of openings in the aortic sinuses varied from 2–5 in the present series; multiple ostia were mostly seen in the anterior sinus. The majority of the ostia lay below the sinutubular ridge (89%) and at or above the level of the upper margin of the cusps (84%). Left ostial openings were mainly centrally located (80%), whereas the right coronary ostia were often shifted towards the right posterior aortic sinus (59%).

DISCUSSION:The preferential location of the ostia was within the sinus and above the cusps, but below the sinutubular ridge. On occasion, normal variants like multiple ostia, vertical or circumferential shift in the position, and slit-like ostia may create confusion in interpreting the images and pose a difficulty during procedures like angiography, angioplasty, and coronary artery bypass grafting.

The coronary arteries arise from the aortic sinuses. The initial portion of the aortic root, which houses the leaflets of the aortic valve, is occupied by the aortic sinuses, also called the sinuses of Valsalva.1 The aortic sinuses reach beyond the upper border of the cusp and form a well-defined, complete, and circumferential sinutubular ridge when viewed from the aortic aspect. These sinuses are named according to their position as the anterior, left posterior, and right posterior aortic sinuses. The right coronary artery arises from the anterior coronary sinus and the left coronary artery from the left posterior aortic sinus. In clinical terminology, the anterior, left posterior, and right posterior sinuses are often called the right, left, and non-coronary sinuses, respectively. Recently, coronary artery anomalies as a cause of coronary heart disease are gaining consideration in the diagnostic workup. One of the subsets of coronary artery anomalies is the anomalous origin. This subgroup has important clinical manifestations, including sudden death, especially in young athletes.3–5 Some authors have indicated the need to establish diagnostic screening protocols for athletes and other young individuals subjected to extreme exertion.6–8 According to Loukas et al. (2009), it is desirable to determine the incidence of the variations, which are potentially capable of inducing sudden cardiac death, in order to analyze the value of screening.8

Most anomalies of origin have been reported as case reports.9–13 The available studies in the literature that report the incidence of anomalous origin of the coronary arteries have drawn their samples either from an autopsy population of congenital heart disease4 or from an angiographic series performed for the work-up of chest pain evaluation.14–16 Therefore, such studies do not provide data on the frequency of occurrence of variations in an unsuspected population. Few systematic studies have described the normal and variant anatomy of coronary artery ostia in an unsuspected population.17– 20

Genetic and geographic variations in the coronaries are a known fact.8, 21–23 Garg et al. (2000)23 and Harikrishnan et al. (2002)24 have reported the incidence of coronary artery anomalies in angiographic studies of the Indian population. The present study describes the normal and variant anatomy of the ostia of the coronary arteries in adult cadavers of Indian origin.

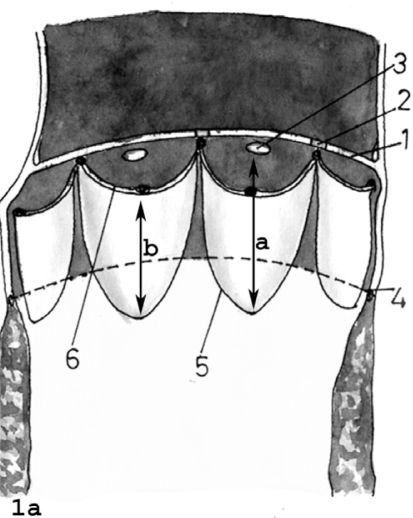

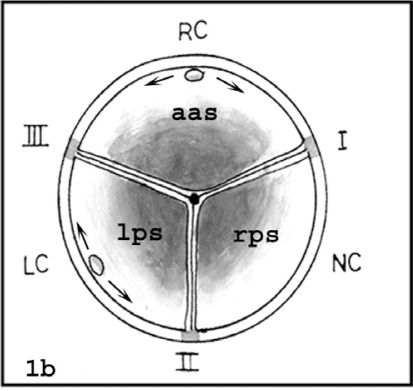

MATERIAL AND METHODSThe study was carried out on 105 embalmed heart specimens preserved in the department of anatomy. These heart specimens were obtained from adult cadavers dissected for undergraduate teaching. The aortic root was opened and the origins of the coronaries were observed. The positions of the ostia were noted with reference to the sinutubular ridge and the cusps. The heights of the cusps and the ostia were measured from the bottom of the aortic sinuses with the help of a sliding vernier caliper. In cases where the ostium was shifted towards one of the commissures, the height of the ostium was not recorded. Positions of the ostia were also observed with reference to the commissures. Figure 1a & b show schematic representations of the aortic root and aortic sinuses.

Schematic diagram of an opened aortic orifice showing: 1 - sinutubular ridge; 2 - commissures; 3 - coronary ostium; 4 - ventriculoarterial junction; 5 - attached margin of the aortic cusp; 6 - free upper margin of the aortic cusp. Arrows a and b indicate the heights of the ostium and the cusp from the bottom of the sinus, respectively

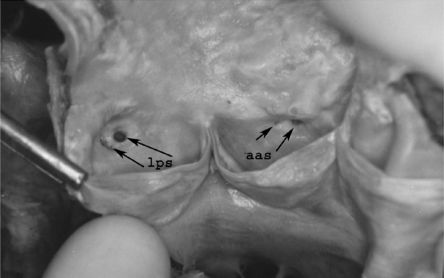

No openings were observed in the pulmonary sinuses or in the right posterior aortic sinus. Table 1 shows the total number of openings in various aortic sinuses. In approximately 36% of the cases, multiple openings were seen in the anterior aortic sinus. The extra openings were minute, of pinhead size. Only in two cases were double openings observed in the left posterior sinus, one in each of the two branches of the left main coronary artery (Figure 2).

Number of cases of single/multiple ostia in the aortic sinuses

| Number of openings | Anterior aortic sinus | Left posterior sinus | Right posterior sinus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65* | 103 | 0 |

| 2 | 31 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

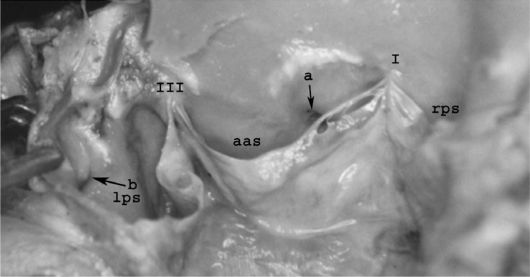

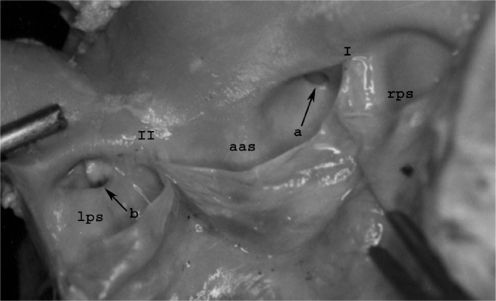

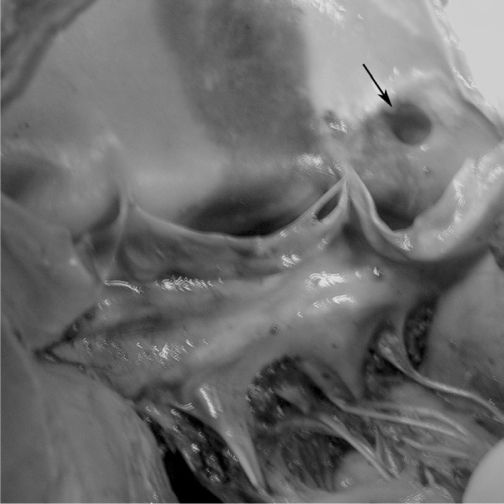

Table 2 shows the positions of the coronary ostia with reference to the cusps and the sinutubular ridge. In the majority of cases, the ostia were positioned below the level of the sinutubular ridge, but above the level of the cusps. Figures 3 through 5 show deviations of the ostia with reference to the sinutubular ridge and the upper margin of the cusp. It was observed that in cases where the ostia were situated just below the sinutubular ridge, the ridge was arched to accommodate the ostia within the sinus (Figure 3).

Positions of the coronary ostia with respect to the sinutubular ridge and the cusps of the aortic valve

| Position with reference to the sinutubular ridge | Position with reference to the upper margin of the cusp of aortic valve | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| above | at | below | above | at | below | |

| Right ostium | 4* | 7 | 94 | 87 | 12 | 6 |

| Left ostium | 5 | 16 | 84 | 82 | 5 | 8 |

Table 3 shows the height of the cusps and the ostia from the bottom of the aortic sinuses.

The right coronary ostia were situated at a higher level than the left.

Table 4 shows the circumferential position of the ostia in the respective sinuses with reference to the commissure. The right ostium was shifted more often from its normal position towards commissure I between the anterior and right posterior sinus (Figure 6). In some cases, the ostia were seen as vertical, horizontal, or crescentic slits. These slits were found in the right coronary ostium in nine cases and in the left coronary ostium in eight cases (Figures 5 & 6).

Positions of the coronary ostia with reference to the commissures

| Location of the ostium | Right coronary | Left coronary |

|---|---|---|

| Central | 43* | 81 |

| Near commissure I | 60 | - |

| Near commissure II | - | 10 |

| Near commissure III | 2 | 14 |

The origins of the coronaries show great variability.2 Occasional cases documenting the anomalous origins of the coronary arteries from the pulmonary artery14,25,26 and from the right posterior (non-coronary) sinus13 have been documented in the literature. A common single ostium or multiple ostia in the right and left anterior interventricular and circumflex branches of the anterior aortic sinus have also been reported.9–11 In an angiographic study of an Indian population, Grag and Tiwari (2000) observed anomalous coronaries in 0.95% of individuals. Of these cases, about 90% were anomalies of origin.23 Harikrishnan et al. (2002) reported an incidence of 0.45%.24 In a dissection study on heart specimens received from medicolegal autopsies and performed by Sahni and Jit (1989), no case of anomalous origin of any coronary artery was found.17 In the present study, we did not find any coronary artery arising from the pulmonary or right posterior aortic sinus.

The right coronary sinus had multiple openings. The extra openings were minute and varied in number from one to three. These openings are of the first branch of the right coronary artery, the infundibular branch. In approximately 8% of hearts, the openings were three or more in number. In such cases, one of the extra ostia may be that of the SA nodal artery. In 50% of cases, the SA nodal artery arises as a branch of the initial part of the right coronary artery. Schlesinger et al. (1949)27 and James (1961)28 have described the origin of the SA nodal artery directly from the aortic sinuses in some instances. Standring et al. (2005) have reported the incidence of extra openings in the right aortic sinus in 36% of individuals.2 Sahni and Jit (1989) reported extra openings in 34.8% of male hearts and 27.8% of female hearts.17 Wolloscheck et al. (2001) reported extra ostia in 65% of cases in an anatomic and transthoracic echocardiographic study.29

In a majority of the cases, the positions of the ostia were below the sinutubular ridge. Valodaver et al. (1975)1 reported a 44% incidence of ostia being present above the sinutubular ridge, while Pejkovic et al. (2008)20 reported a very high incidence of ostia at or above the level of the sinutubular junction (82% left and 90% right). Turner and Navratnam (1996) found that 62 of the 74 main coronary ostia lay either at or immediately below the sinutubular ridge.19

The observations from this study are similar to the observations by Sahni and Jit (1989). They reported higher origins in the range of 1.7 - 7.0% with variations between males and females and for the right and left coronary ostia in the Indian population.17 In some cases, even when the ostia were above the level of commissures, the sinutubular ridge arched over the ostial opening rather than being straight. The discrepancy in the findings described above might be due to overlooking the arched pattern of the sinutubular ridge. In about 7% of the hearts, we found ostial openings below the upper margin of the cusps. It is known that during normal function, the cusps do not flatten against the sinus walls, even at maximum systolic pressure.2 Such a situation, however, can arise only in aortic valve dysfunction, which may then lead to blockage of the coronary ostia. Few such cases have been reported in the literature.30

In the majority of cases in the present study, the positioning of the ostia was above the margin of the cusp and below the sinutubular ridge. This observation suggests that the positioning of the ostium within the sinus, rather than at or above the ridge, is functionally advantageous.

Support for this assumption comes from the fact that the thickness of the wall of the aortic sinus at mid-level is half of the thickness of the aortic wall and one quarter of the thickness of the sinutubular ridge.2 This finding suggests that the initial portion of the coronaries negotiates a thinner wall when arising within the sinus. Further studies are required to determine whether positioning of the ostia at or above the ridge or below the level of the cusps is disadvantageous to coronary filling in any way.

It was observed that the right coronary ostium tended to deviate more often towards Commissure I. Turner and Navratnam (1996) documented similar observations.19 This observation seems logical because the course taken by the right coronary artery is forward and to the right, and Commissure I lies to the right of the anterior aortic sinus. The left coronary artery is positioned near its origin in such a way that it lies posterior to the pulmonary trunk and then follows a course that is anterior and to the left. Therefore, its ostial position remains either central or moves toward Commissure III, if the pulmonary trunk is relatively anterior.

Circumferential deviation does not seem to be very functionally significant. However, knowledge of the frequency of circumferential deviation and also of measurements of cusp height and ostial height from the bottom of the sinus will be of help to radiologists in interpreting images of the coronary origins and to clinicians during procedures like angiography and angioplasty. Wolloscheck et al. (2001)29 observed that attachment of aortic leaflets proved to be very useful as landmarks during transthoracic echocardiography.

Of the 105 hearts studied, we found two cases of an absent left main coronary artery (i.e., separate ostia for the left anterior descending and circumflex arteries). In a large angiographic series, Topaz et al. (1991)15 found the incidence to be 0.4%. They also observed that, in 39% of such patients, difficulties in selectively cannulating the separate ostium of the circumflex artery and adequately opacifying this vessel resulted in the need to change the diagnostic catheter size. They also suggested that recognition of this coronary anomaly is necessary to ensure accurate angiographic interpretation and is important for patients undergoing cardiac surgery for selectively perfusing these separate vessels during cardiopulmonary bypass.

Slit-like ostia were seen in a number of cases. There have been reported cases of sudden death in young individuals where the coronary ostia were found to be slit-like at autopsy.31 Slit-like ostia are often associated with acute angulations of the initial part of the coronary artery and predispose individuals to ischemia of the myocardium.23 However, the compromise of the blood supply appears to be due to acute angulations rather than a result of the stretching and subsequent narrowing of the fibroelastic walls of the aortic sinuses, as suggested by Garg and Tiwari (2000).23 The filling of the coronaries occurs mostly during diastole2 and it therefore seems unlikely that systolic stretching and further reduction in the ostial size can have any significant effect on myocardial perfusion.

CONCLUSIONSThe present study describes the normal and variant anatomy of the ostia of the coronary arteries in an unsuspected population. It provides a basis for understanding the normal variants, for determining the incidence of anomalies, and for evaluating the value of screening for such anomalies.

No openings were observed in the pulmonary sinuses or the right posterior aortic sinus. The number of openings in the aortic sinuses varied from 2 - 5 in the present series; multiple ostia were mostly seen in the right sinus. The majority of the ostia lie below the sinutubular ridge (89%) and at or above the level of the upper margin of the cusps (84%). The left openings are mainly centrally located (80%), whereas the right ostium is most often shifted towards the right posterior aortic sinus (59%).

On occasion, normal variants, such as multiple ostia, vertical or circumferential shift in position, and slit-like ostia, may confuse interpretation of the images and may pose a difficulty during procedures, such as angiography, angioplasty, and coronary artery bypass grafting.