Summarize the evidence on drug therapies for obstructive sleep apnea.

MethodsThe Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed. PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, SciELO, LILACS, Scopus, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched on February 17th, 2023. A search strategy retrieved randomized clinical trials comparing the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) in pharmacotherapies. Studies were selected and data was extracted by two authors independently. The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. RevMan 5.4. was used for data synthesis.

Results4930 articles were obtained, 68 met inclusion criteria, and 29 studies (involving 11 drugs) were combined in a meta-analysis. Atomoxetine plus oxybutynin vs placebo in AHI mean difference of -7.71 (-10.59, -4.83) [Fixed, 95 % CI, I2 = 50 %, overall effect: Z = 5.25, p < 0.001]. Donepezil vs placebo in AHI mean difference of -8.56 (-15.78, -1.33) [Fixed, 95 % CI, I2 = 21 %, overall effect: Z = 2.32, p = 0.02]. Sodium oxybate vs placebo in AHI mean difference of -5.50 (-9.28, -1.73) [Fixed, 95 % CI, I2 = 32 %, overall effect: Z = 2.86, p = 0.004]. Trazodone vs placebo in AHI mean difference of -12.75 (-21.30, -4.19) [Fixed, 95 % CI, I2 = 0 %, overall effect: Z = 2.92, p = 0.003].

ConclusionThe combination of noradrenergic and antimuscarinic drugs shows promising results. Identifying endotypes may be the key to future drug therapies for obstructive sleep apnea. Moreover, studies with longer follow-up assessing the safety and sustained effects of these treatments are needed.

PROSPERO registration numberCRD42022362639.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is a condition in which repetitive upper airway closure occurs during sleep, leading to decreased oxygen saturation and impaired sleep architecture.1 It is estimated to affect one billion people worldwide2 and is associated with cardiometabolic risk and cognitive impairment.3

There are many treatments for OSA, such as behavioral measures, myofascial exercises, oral appliances, surgeries, Positive Airway Pressure (PAP), and hypoglossal nerve stimulators.4 Although PAP treatment remains the leading choice for moderate and severe OSA, its adherence rate is low.5

Recent research on the pathophysiology brought light to possible targets for pharmacotherapy.6 The OSA pathophysiological traits (endotypes) are the anatomy of the upper airway susceptible to collapse; the poor pharynx dilator muscle responsiveness; the low arousal respiratory threshold; and the oversensitive ventilatory control system (high loop gain).7

Drug therapy for the management of sleep apnea has been investigated, but no robust evidence that supports its benefits has been found to date.8

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to summarize the evidence on pharmacotherapy for the treatment of OSA in adults.

MethodsThis review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.9 The protocol is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO CRD42022362639).

Inclusion criteriaRandomized Clinical Trials (RCT) compared the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) of pharmacotherapies for adults with OSA.

PICOT strategy- -

Population/Participants: Adults diagnosed with OSA.

- -

Intervention: Any drug therapy intended to treat OSA.

- -

Comparator/Control: Placebo.

- -

Outcomes: AHI.

- -

Type of study: RCT.

There was no patient or public involvement.

Search strategyPubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, SciELO, LILACS, Scopus, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched with no limitations to date or language. All electronic databases were searched on February 2023. The search strategy to be used in PubMed is presented in Table 1.

Search Strategy for PubMed.

The articles were imported to Rayyan, and duplicates were removed. Two authors independently screened by title, abstract, and full text to determine inclusion criteria. A third reviewer resolved the discrepancies.

Data extraction and managementTwo independent authors extracted data from the included studies. The latter were inserted into a database. Meta-analysis was conducted for the studies that could be combined.

Risk of bias assessmentTwo reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (RoB 2).10 Each study was evaluated for the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported results.

Assessment of heterogeneityThe I2 statistics were used to assess heterogeneity, below 25 % was considered low heterogeneity, between 25 % and 50 % moderate heterogeneity, and above 50 % high heterogeneity.

Measures of the treatment effectAHI was extracted as a continuous variable, and the mean difference with a 95 % Confidence Interval was used. This was performed using Review Manager (RevMan 5.4) software.

AnalysisRevMan 5.4 was used to perform the statistical analysis. In the heterogeneity assessment, when I2 was > 50 %, a random-effects model was used, otherwise, a fixed-effect model was applied.

Grading quality of evidenceThe Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to evaluate the strength of the evidence of the systematic review results.11

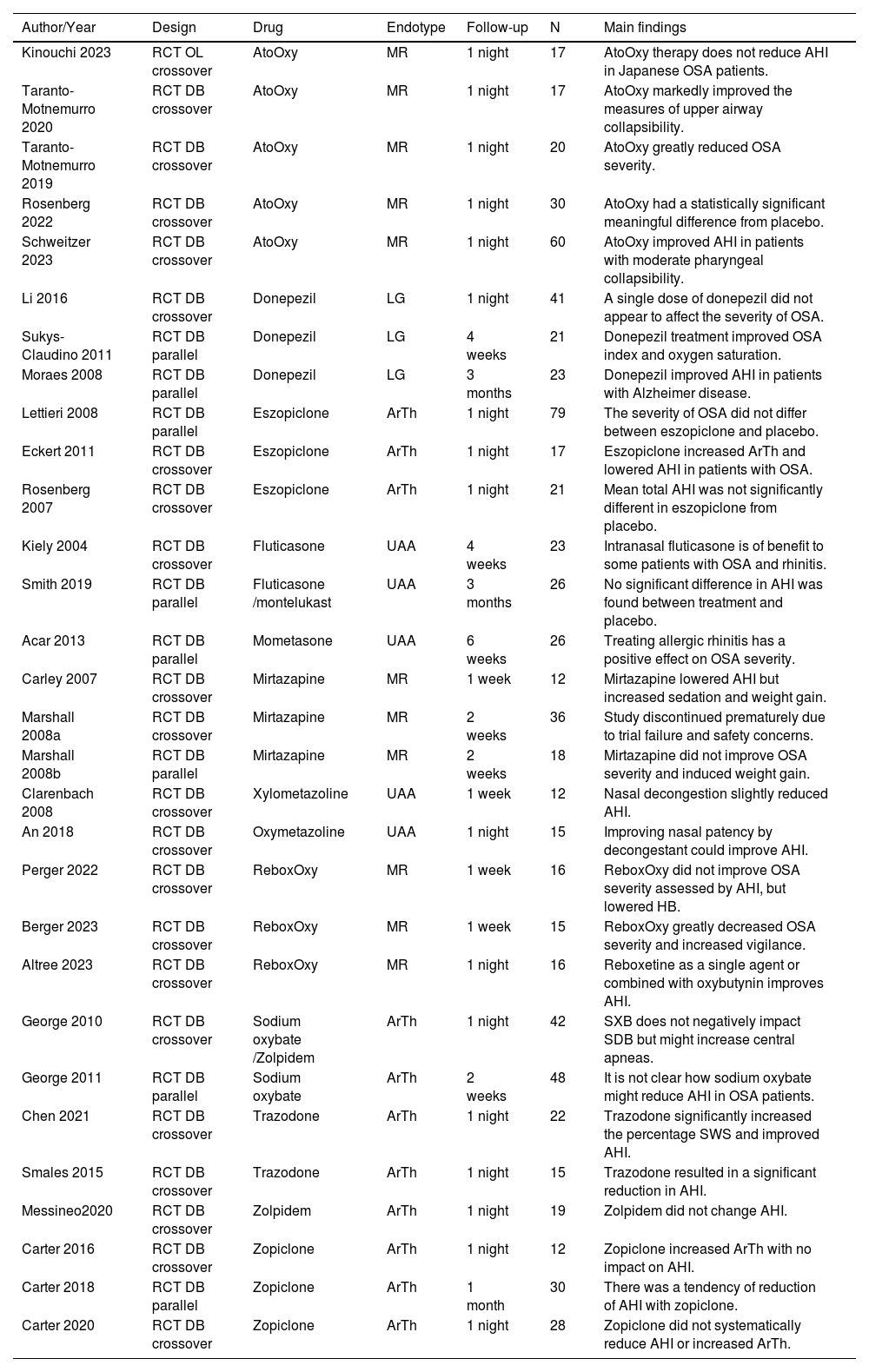

ResultsThe database search retrieved 4930 articles, duplicates were removed, and two independent authors screened 3900 titles, 319 were assessed for eligibility by abstract. 68 of which met the inclusion criteria, and finally, 29 studies could be combined in the meta-analysis (11 drugs). The PRISMA flow diagram summarizes the selection process (Fig. 1). Qualitative synthesis is shown in Table 2.

Qualitative synthesis of the included studies.

RCT, Randomized Clinical Trial, DB, Double-Blind; OL, Open-Label; MR, Muscle Responsiveness; LG, Loop Gain; ArTh, Arousal Threshold; UAA, Upper Airway Anatomy; AHI, Apnea-Hypopnea Index; AtoOxy, Atomoxetine + Oxybutynin; ReboxOxy, Reboxetine + Oxybutynin, OSA, Obstructive Sleep Apnea; HB, Hypoxic Burden; SWS, Slow Wave Sleep.

A few different drug mechanisms can potentially target the collapsibility of the upper airway, such as weight loss medication that can reduce fat tissue on the tongue base and neck, diuretics reducing fluid retention, and nasal obstruction can be approached with intranasal steroids and decongestants.6

Both the use of nasal steroids (3 studies) and, nasal decongestants (2 studies) versus placebo showed a tendency for improvement in AHI, without statistical significance (Fig. 2).12-16

Muscle responsivenessThe combination of noradrenergic and antimuscarinic drugs was tested in different trials, Atomoxetine plus Oxybutynin (AtoOxy) showed significant improvement in AHI with combined data from 5 studies, mean difference of −7.71 (−10.59, −4.83) [Fixed, 95 % CI, I2 = 50 %, overall effect: Z = 5.25, p < 0.001].17-21 Reboxetine plus Oxybutynin (ReboxOxy) was assessed in 3 studies, and although there was a tendency for improvement, no significance was found (Fig. 2).22-24

Mirtazapine was tested by two authors in 3 trials, none of which evidenced the benefits of this drug treatment for OSA, moreover, one of these trials was discontinued due to trial failure and safety concerns.25,26

Arousal thresholdEszopiclone, zolpidem, and zopiclone were studied and showed no difference in AHI from placebo.27-33 Sodium Oxybate (SXB) and trazodone showed significant improvement in AHI. SXB vs placebo in AHI (2 studies, 90 patients) mean difference of −5.50 (−9.28, −1.73) [Fixed, 95 % CI, I2 = 32 %, overall effect: Z = 2.86, p = 0.004].34,35 Trazodone vs placebo in AHI (2 studies, 37 patients) mean difference of −12.75 (−21.30, −4.19) [Fixed, 95 % CI, I2 = 0 %, overall effect: Z = 2.92, p = 0.003].36,37

Loop gainConcerning loop gain, the only drug with enough studies that met inclusion criteria and could be combined into a meta-analysis was donepezil. Three studies assessed its effect on AHI against placebo demonstrating improvement in OSA severity, with a mean difference of −8.56 (−15.78, −1.33) [Fixed, 95 % CI, I2 = 21 %, overall effect: Z = 2.32, p = 0.02].38-40

Risk of bias assessmentThe majority of the studies included were double-blind randomized control trials with an overall low risk or with some concerns of bias (Fig. 3). The strength of the evidence was assessed by GRADE (Fig. 4).

DiscussionThe combination of atomoxetine and oxybutynin was found to provide the most significant enhancement in OSA severity.17-21 Nevertheless, all studies with this treatment were single-night studies with small sample sizes.

Historically, the use of drugs that would increase the arousal threshold in patients was thought to worsen apnea by decreasing muscle dilator response and promoting collapsibility. However, the use of zolpidem, eszopiclone, and zopiclone was found not to impact OSA severity compared to placebo.27-33 Moreover, sodium oxybate and trazodone showed improvement in AHI.34-37

It is important to frame that this study only brings data from primary studies that met the defined inclusion criteria and could be combined in a meta-analysis. A limitation is that drugs that have been tested by a single RCT have not been included. There is also heterogeneity among populations included in different trials that were combined, such as different degrees of OSA severity which may impact drug efficacy.

Moreover, to better understand physio-pathological endotypes other outcomes such as loop gain, arousal threshold, muscle compensation, and hypoxic burden could be assessed.

ConclusionWhile numerous drugs have been investigated, only a few have shown promising results, like the combination of noradrenergic and antimuscarinic drugs. Identifying endotypes that respond to each pharmacological mechanism may be the key to future drug therapies for OSA. Moreover, studies with longer follow-up periods assessing the safety and sustained effects of these treatments are needed.

Authors’ contributionsNobre ML was responsible for the study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, and critical revision. Sarmento ACA, Oliveira PF, and Wanderley FF were responsible for the interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, and critical revision. Diniz Júnior J was responsible for the study conception and design, drafting of the manuscript and critical revision. Gonçalves AK was responsible for the study conception and design, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and critical revision.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.