Premedication is important in pediatric anesthesia. This meta-analysis aimed to investigate the role of dexmedetomidine as a premedicant for pediatric patients.

A systematic literature search was conducted to identify randomized controlled trials comparing dexmedetomidine premedication with midazolam or ketamine premedication or placebo in children. Two reviewers independently performed the study selection, quality assessment and data extraction. The original data were pooled for the meta-analysis with Review Manager 5. The main parameters investigated included satisfactory separation from parents, satisfactory mask induction, postoperative rescue analgesia, emergence agitation and postoperative nausea and vomiting.

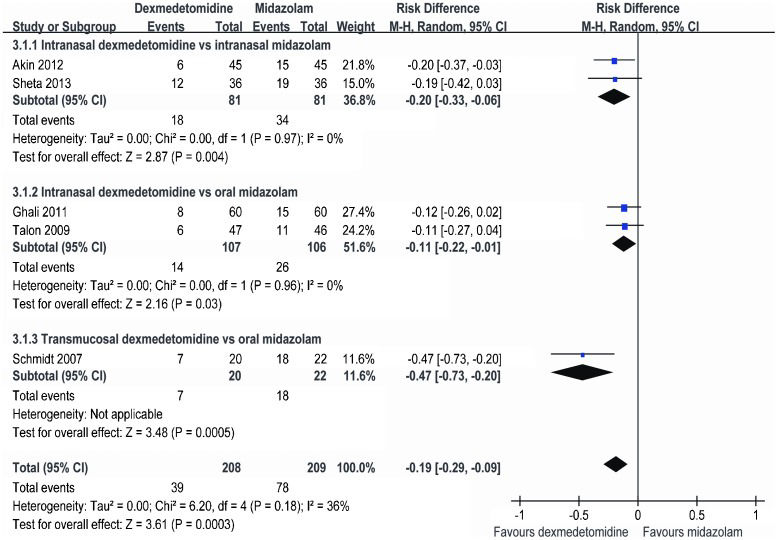

Thirteen randomized controlled trials involving 1190 patients were included. When compared with midazolam, premedication with dexmedetomidine resulted in an increase in satisfactory separation from parents (RD = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.06 to 0.30, p = 0.003) and a decrease in the use of postoperative rescue analgesia (RD = -0.19, 95% CI: -0.29 to -0.09, p = 0.0003). Children treated with dexmedetomidine had a lower heart rate before induction. The incidence of satisfactory mask induction, emergence agitation and PONV did not differ between the groups. Dexmedetomidine was superior in providing satisfactory intravenous cannulation compared to placebo.

This meta-analysis suggests that dexmedetomidine is superior to midazolam premedication because it resulted in enhanced preoperative sedation and decreased postoperative pain. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the dosing schemes and long-term outcomes of dexmedetomidine premedication in pediatric anesthesia.

At least 60% of pediatric patients experience preoperative anxiety 1. Children may become overly uncooperative at the time of separation from parents, venipuncture, or mask application. Untreated anxiety can lead to difficult induction, increased postoperative pain, greater analgesic requirements, emergence agitation and even postoperative psychological effects and behavioral issues 2-7. Despite the many advances in nonpharmacologic interventions, practitioners still rely on sedative premedicants 8,9.

Midazolam, which causes sedation, anxiolysis and amnesia, is one of the most frequently used premedicants 10-14. It has additional beneficial properties, such as anticonvulsant activity, rapid onset and a short duration of action and it reduces postoperative vomiting 12,. However, it is far from an ideal premedicant due to its undesirable effects, which include restlessness, paradoxical reactions, cognitive impairment, postoperative behavioral changes and respiratory depression 19-21. Ketamine is another popular premedicant that causes dissociative anesthesia and it has both sedative and analgesic properties 22,23. However, its side effects, such as excessive salivation, nausea and vomiting, nystagmus, hallucination and postoperative psychological disturbances have limited its use 24-26.

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective α-2 adrenoceptor agonist that provides sedation, anxiolysis and analgesic effects without causing respiratory depression 27. Recently, it has been explored extensively in the pediatric population. Although several randomized controlled trials have focused on dexmedetomidine premedication in children, the sample sizes have been relatively small and differing conclusions have been reported. Thus, the evidence supporting the use of dexmedetomidine is unclear. This meta-analysis was conducted to investigate the effects of premedication with dexmedetomidine on preoperative sedation, hemodynamic stability, postoperative pain and possible adverse events in pediatric patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODSSearch strategy and trial selectionThis systematic review of randomized controlled trials was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 28. Two researchers (K.P. and SR.W.) independently searched the following databases up to April 2014: MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). The terms used in the search strategy were as follows: 1) dexmedetomidine AND (premedication* OR premedicant* OR preoperative OR pre anesthesia OR pre anaesthesia) AND (child* OR pediatric* OR paediatric*) for the MEDLINE and CENTRAL searches and 2) ‘dexmedetomidine‘/exp OR dexmedetomidine AND (premedication* OR premedicant* OR preoperative OR preanesthesia OR preanaesthesia) AND (child* OR pediatric* OR paediatric*) for the EMBASE search.

All searches were performed without language or publication date restrictions. The results were collated and deduplicated in Endnote X7 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY). The titles and abstracts were screened before retrieval of the full articles. Any controversy concerning study selection or data extraction was resolved by consensus with a third reviewer (HF.J.). All three authors read the full texts of all papers and determined which papers should be included or excluded.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaTo be eligible for this meta-analysis, publications were required to meet the following four inclusion criteria: 1) original research comparing premedication with dexmedetomidine to premedication with midazolam or ketamine or placebo as the sole agent administered through noninvasive routes (oral, rectal, intranasal, sublingual and buccal) in pediatric patients undergoing elective procedures; 2) a randomized controlled trial (RCT) study design; 3) disclosure of at least one of the following outcome measures: quality of separation from parents, quality of mask induction, hemodynamic variables, postoperative pain, recovery time, time to discharge from the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), emergence agitation (EA), postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), shivering and other possible untoward events; and 4) availability of the full-text article.

Data extraction and quality assessmentThe following data from the included studies were extracted and tabulated by two researchers (K.P. and SR.W.): author, year of publication, sample size, mean age, intervention measure, type of procedure, anesthesia scheme and any outcome that met the inclusion criteria. Corresponding authors were contacted to obtain missing data if necessary. For the trials assessing different premedication doses, the groups were combined to create a single pair-wise comparison 29.

The validity was assessed and scored by two researchers (SR.W. and J.L.) and checked by a third researcher (FH.J.) using the Jadad scale 30,31, which considers the reporting and adequacy of randomization (2 points), double blinding (2 points) and description of drop-outs (1 points).

Statistical analysisWhen outcomes of interest were reported by two or more studies, the included articles were pooled and weighted using Review Manager (version 5.1, 2011; the Nordic Cochrane Center, the Cochrane Collaboration). Categorical outcomes are reported as risk differences (RDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), while continuous outcomes are reported as weighted mean differences (WMDs) and 95% CIs.

Heterogeneity, which was assessed using I2 statistics, describes the percentage variability in effect estimates (RD or WMD) that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. A random-effect model was used for the analysis. Publication bias was assessed visually with a funnel plot if more than 10 studies were included.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to further test the robustness of the results. These analyses included 1) an assessment of the influence of publication quality (high versus low quality) on the results and 2) subgroup analysis according to the different routes of premedication administration.

RESULTSIncluded trialsA total of 171 of the articles were relevant to the search terms. Screening of the titles and abstracts revealed that 21 studies were potentially eligible for inclusion. After reading the full-text articles, 13 trials (published between 2007 and 2014) involving 1190 participants were finally included in this meta-analysis 32-44 (Table1). A flow diagram depicting the trial selection process is shown in Figure1.

-Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Intervention time and dosing scheme | N | Age (y) | Procedure | Anesthesia | Jadad score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linares Segovia 2014 | 1. Intranasal dexmedetomidine 1 µg/kg (0.5 ml) at 60 min before induction | 52 | 4 | Inguinal hernia repair, umbilical hernia repair, circumcision | No details provided | 4 |

| 2. Oral midazolam 0.5 mg/kg at 60 min before induction | 56 | 4 | ||||

| Sheta 2013 | 1. Intranasal dexmedetomidine 1 µg/kg (1 ml) at 45-60 min before induction | 36 | 3.9 | Complete dental rehabilitation | Sevoflurane + N2O + local anesthesia | 5 |

| 2. Intranasal midazolam 0.2 mg/kg (1 ml) at 45-60 min before induction | 36 | 4.2 | ||||

| Pant 2013 | 1. Sublingual dexmedetomidine 1.5 µg/kg (undiluted) at 45 min before induction | 50 | 4.5 | Inguinal hernia repair, orchidopexy, circumcision | Sevoflurane + N2O + caudal block | 5 |

| 2. Sublingual midazolam 0.25 mg/kg (undiluted) at 20 min before induction | 50 | 2 | ||||

| Mostafa 2013 | 1. Intranasal dexmedetomidine 1 µg/kg at 30 min before induction | 32 | 5 | Bone marrow biopsy and aspiration | Sevoflurane | 3 |

| 2. Intranasal midazolam 0.2 mg/kg at 30 min before induction | 32 | 4.8 | ||||

| 3. Intranasal ketamine 5 mg/kg at 30 min before induction | 32 | 4.9 | ||||

| Gyanesh 2013 | 1. Intranasal dexmedetomidine 1 µg/kg (1 ml) at 60 min before IV cannulation | 52 | 5.1 | Magnetic resonance imaging | Propofol (sedation only) | 5 |

| 2. Intranasal ketamine 5 mg/kg (1 ml) at 30 min before IV cannulation | 52 | 4.9 | ||||

| 3. Placebo | 46 | 5 | ||||

| Akin 2012 | 1. Intranasal dexmedetomidine 1 µg/kg (1.5 ml) at 45-60 min before induction | 45 | 5 | Adenotonsillectomy | Sevoflurane + N2O | 5 |

| 2. Intranasal midazolam 0.2 mg/kg (1.5 ml) at 45-60 min before induction | 45 | 6 | ||||

| Ozcengiz 2011 | 1. Oral dexmedetomidine 2.5 µg/kg at 40-45 min before induction | 25 | 5.5 | Esophageal dilatation procedures | Sevoflurane + N2O | 4 |

| 2. Oral midazolam 0.5 mg/kg at 40-45 min before induction | 25 | 4.9 | ||||

| 3. Placebo | 25 | 6.2 | ||||

| Mountain 2011 | 1. Oral dexmedetomidine 4 µg/kg at 30 min before entering the operating room | 22 | 4 | Dental restoration, tooth extraction | Sevoflurane + N2O + local anesthesia | 4 |

| 2. Oral midazolam 0.5 mg/kg at 30 min before entering the operating room | 19 | 4 | ||||

| Ghali 2011 | 1. Intranasal dexmedetomidine 1 µg/kg (0.5 ml) at 60 min before induction | 60 | 8.2 | Outpatient adenotonsillectomy | Sevoflurane + N2O | 4 |

| 2. Oral midazolam 0.5 mg/kg at 30 min before induction | 60 | 8.1 | ||||

| Yuen 2010 | 1. Intranasal dexmedetomidine 1 µg/kg (0.4 ml) at 30-75 min before IV cannulation | 79 | 4 | Elective surgery (no details provided) | No details provided | 5 |

| 2. Placebo | 21 | 4 | ||||

| Talon 2009 | 1. Intranasal dexmedetomidine 2 µg/kg (atomization) at 30-40 min before induction | 50 | 9.5 | Reconstructive surgery | Isoflurane + N2O | 4 |

| 2. Oral midazolam 0.5 mg/kg at 30-40 min before induction | 50 | 10.7 | ||||

| Yuen 2008 | 1. Intranasal dexmedetomidine 1 µg/kg (0.4 ml) at 60 min before induction | 32 | 6.1 | Orchidopexy, excision of lymph nodes, circumcision | Isoflurane + N2O + regional anesthesia | 5 |

| 2. Intranasal dexmedetomidine 0.5 µg/kg (0.4 ml) at 60 min before induction | 32 | 6.8 | ||||

| 3. Oral midazolam 0.5 mg/kg at 30 min before induction | 32 | 6.4 | ||||

| Schmidt 2007 | 1. Transmucosal dexmedetomidine 1 µg/kg at 45 min before surgery | 20 | 8 | Excision of lymph nodes, herniorrhaphy, circumcision | Sevoflurane/isoflurane + N2O + Regional anesthesia | 3 |

| 2. Oral midazolam 0.5 mg/kg at 30 min before induction | 22 | 9 |

Table1 presents the characteristics of the included trials, which were all randomized controlled trials that investigated pediatric patients undergoing different procedures (dental rehabilitation and tooth extraction, lymph node excision, herniorrhaphy, circumcision, bone marrow biopsy and aspiration, adenotonsillectomy and others). The children ranged in age from 2 to 10 years old and most were 4 to 6 years old.

Eleven trials compared dexmedetomidine with midazolam premedication 32-35,37-40, two compared dexmedetomidine with ketamine 35,36 and three compared dexmedetomidine with a placebo 36,38,41. All trials administered premedication through noninvasive routes, including oral and transmucosal (intranasal, sublingual and buccal) administration, at 30-75 min before commencement of surgery. The dosing scheme for dexmedetomidine was 1-2 µg/kg for transmucosal premedication or 2.5-4 µg/kg for oral premedication. Ten trials used balanced inhalational general anesthesia with sevoflurane or isoflurane and one trial provided sedation with propofol.

Effect of dexmedetomidine versus midazolam on separation from parentsSeven trials including 650 patients compared dexmedetomidine versus midazolam premedication for satisfactory separation from parents 32,33,35,37,40,42,43. The meta-analysis revealed that more children experienced satisfactory separation following treatment with dexmedetomidine (RD = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.06 to 0.30, p = 0.003) (Figure2). Subgroup analysis showed that RD = 0.10 (95% CI: -0.12 to 0.31) for intranasal dexmedetomidine versus intranasal midazolam and RD = 0.24 (95% CI: 0.10 to 0.38) for intranasal dexmedetomidine versus oral midazolam. However, there was significant heterogeneity among the pooled studies (I2 = 73%).

Effect of dexmedetomidine versus midazolam on mask inductionSix trials including 475 patients compared satisfactory mask induction in children treated with dexmedetomidine versus midazolam 32,33,37,39,42,43. The meta-analysis showed that there was no significant difference between the groups (RD = -0.01, 95% CI: -0.16 to 0.14, p = 0.88) (Figure3). The subgroup analysis revealed that RD = -0.00 (95% CI: -0.44 to 0.43) for intranasal dexmedetomidine versus intranasal midazolam and RD = 0.01 (95% CI: -0.19 to 0.21) for intranasal dexmedetomidine versus oral midazolam. This analysis was influenced by heterogeneity (I2 = 75%).

Effects of dexmedetomidine versus midazolam on heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP) and oxygen saturation (SpO2) before inductionTwo trials including 162 patients compared HR before induction in children treated with dexmedetomidine versus midazolam 40,44. The meta-analysis revealed that the HR before induction was significantly lower in the children treated with dexmedetomidine (WMD = -15.49 beats/min, 95% CI: -25.13 to -5.86 beats/min, p = 0.002). This analysis was influenced by heterogeneity (I2 = 74%).

Two trials including 184 patients compared systolic blood pressure (SBP) before induction in children treated with dexmedetomidine versus midazolam 35,40. There was no significant difference between the groups (WMD = -7.13 mmHg, 95% CI: -19.02 to 4.75 mmHg, p = 0.24). This analysis was influenced by heterogeneity (I2 = 99%).

Two trials including 184 patients compared SpO2 before induction in children treated with dexmedetomidine versus midazolam 35,40. The meta-analysis showed that there was no significant difference between the groups (WMD = 0.27%, 95% CI: -0.21 to 0.74%, p = 0.27). Additionally, no significant heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 0%).

Effects of dexmedetomidine versus midazolam on recovery time and time to discharge from the PACUThree trials including 204 patients compared the recovery times of children treated with dexmedetomidine versus midazolam 33,37,44. There was no significant difference between the groups (WMD = -0.45 min, 95% CI: -1.26 to 0.35 min, p = 0.27) and no significant heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 0%).

Three trials including 234 patients compared the time to discharge from the PACU for children treated with dexmedetomidine versus midazolam 33,40,44. There was no significant difference between the groups (WMD = 0.45 min, 95% CI: -2.33 to 3.23 min, p = 0.75). This analysis was influenced by heterogeneity (I2 = 62%).

Effect of dexmedetomidine versus midazolam on postoperative rescue analgesiaFive trials including 417 patients compared dexmedetomidine with midazolam premedication for postoperative rescue analgesia 33,37,40,42,44. Meta-analysis revealed that fewer children needed rescue analgesia when they were treated with dexmedetomidine (RD = -0.19, 95% CI: -0.29 to -0.09, p = 0.0003) (Figure4). The subgroup analysis showed that RD = -0.20 (95% CI: -0.33 to -0.06) for intranasal dexmedetomidine versus intranasal midazolam and RD = -0.11 (95% CI: -0.22 to -0.01) for intranasal dexmedetomidine versus oral midazolam. This analysis was influenced by heterogeneity (I2 = 36%); however, no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) was detected in the subgroup analysis.

Effects of dexmedetomidine versus midazolam on EA and PONVFive trials including 346 patients compared dexmedetomidine with midazolam premedication for EA treatment 33,37-39,. There was no significant difference between the groups (RD = -0.03, 95% CI: -0.10 to 0.04, p = 0.36) (Figure5). Subgroup analysis showed that RD = -0.05 (95% CI: -0.16 to 0.06) for intranasal dexmedetomidine versus intranasal midazolam and RD = -0.03 (95% CI: -0.17 to 0.10) for oral dexmedetomidine versus oral midazolam. This analysis was influenced by heterogeneity (I2 = 42%)

Three trials including 226 patients compared dexmedetomidine with midazolam premedication for PONV treatment 33,35,37. The meta-analysis showed that there was no significant difference between the groups (RD = -0.01, 95% CI: -0.06 to 0.04, p = 0.83) (Figure6) and no significant heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 0%).

Dexmedetomidine versus ketamineNone of the data illustrating the effects of dexmedetomidine versus ketamine could be pooled because similar outcomes were not reported by any two trials 35,36.

Effect of dexmedetomidine versus placebo on intravenous cannulationTwo trials including 198 patients compared satisfactory intravenous cannulation in patients treated with dexmedetomidine versus placebo 36,41. The meta-analysis revealed that more children had satisfactory intravenous cannulation following treatment with dexmedetomidine (RD = -0.48, 95% CI: -0.92 to -0.04, p = 0.03). However, this analysis was significantly influenced by heterogeneity (I2 = 91%).

DISCUSSIONThe current meta-analysis revealed that dexmedetomidine premedication of pediatric patients resulted in more satisfactory separation from parents and a reduced need for postoperative rescue analgesia compared with midazolam. The dexmedetomidine-premedicated children had lower HRs before induction.

Although premedication is often applied, the ideal agent and the best route of administration remain unclear 45. Oral premedication is the most widely used route; however, it results in low bioavailability 46,47. Rectal application is often painful and medications administered in this way may be easily expelled from the rectum in young children and can be problematic for use in older children. Intramuscular premedication has also been used, but it is invasive and should be avoided if possible. Transmucosal routes, including intranasal, sublingual and buccal administration, have been shown to be effective because of the rich mucosal blood supply and because administration via these routes allows for the bypass of first-pass metabolism. Moreover, compliance with nasal sedation is easier to achieve than compliance with oral sedation in young children 48. In this meta-analysis, all included trials administered premedication through noninvasive routes, including oral and transmucosal (intranasal, sublingual, or buccal) routes.

The pharmacokinetics of midazolam administration has been well studied. When given orally, its acceptability by children is only 70% due to poor palatability 49. Intranasal administration of this medication is effective; however, it may cause nasal irritation 12. Midazolam results in rapid sedation and most of the included studies in this meta-analysis administered intranasal or oral midazolam at 30 min before induction or surgery. Dexmedetomidine, on the other hand, is colorless, odorless and tasteless and several studies have investigated its pharmacokinetics in children 50-54. Oral administration of dexmedetomidine also results in poor bioavailability. Although intranasal premedication with midazolam causes nasal irritation, none of the children treated with dexmedetomidine showed signs of nasal irritation 33. Intranasal dexmedetomidine is commonly administered 45-60 min before induction of surgery because of the relatively slow onset of maximal sedation.

This meta-analysis revealed that dexmedetomidine was superior to midazolam in producing satisfactory sedation in children separated from their parents. The subgroup analysis showed that premedication with intranasal dexmedetomidine seemed to be more effective than premedication with oral midazolam. Oral premedication is associated with low and variable bioavailability, which may lead to underdosage. This fact may explain the reduced effectiveness of oral midazolam. Notably, larger volumes of intranasally administered drugs may be swallowed before there is sufficient time for absorption, leading to reduced bioavailability 33. However, the intranasal drug volumes differed among the studies (range, 0.3 to 1.5 ml). This finding may have contributed to the discrepancies among the included studies and may have introduced bias.

The superiority of dexmedetomidine over midazolam vanished at the time of mask application. Unlike conventional sedatives, the site of action of dexmedetomidine is the central nervous system, primarily the locus coeruleus, in which it induces sedation that parallels natural sleep 55. Therefore, it is not surprising that external stimulation facilitates arousal. However, clonidine, which is another α-2 adrenoceptor agonist, was found to be superior to midazolam in providing acceptable levels of sedation during induction in another meta-analysis 56.

Compared with midazolam premedication, dexmedetomidine premedication reduced the HR during the preoperative sedation period after induction. The children in both groups maintained similar normal SpO2 values. Dexmedetomidine can decrease sympathetic outflow by decreasing plasma epinephrine and norepinephrine levels, thus leading to decreases in HR and BP 57,58. Additionally, it has been shown to have minimal effects on respiration 59,60, which is its key advantage over other sedative medications.

The most frequently reported adverse events associated with dexmedetomidine treatment are hypotension and bradycardia 61. Its hemodynamic effects are well known following intravenous infusion (there is a higher risk of bradycardia in patients receiving a rapid bolus and a lower risk in those receiving a continuous infusion). However, these side effects are seldom observed following non-intravenous administration. Yuen et al. 43 have shown that intranasal dexmedetomidine premedication decreases HR by 11% after administration of 0.5 µg/kg and by 16% after administration of 1 µg/kg compared with their respective baseline values within 60 min. Another study 41 has found that the maximum reduction in SBP is 13.2% at 60 min and the maximum reduction in HR is 14.9% at 75 min after administration of 1 µg/kg intranasal dexmedetomidine premedication. None of the included trials reported significant hypotension or bradycardia requiring treatment in either group during the study period.

Dexmedetomidine has been demonstrated to effectively reduce opioid requirements and to potentiate analgesia 61-63. The current meta-analysis reported the same outcome: the patients treated with dexmedetomidine required less postoperative rescue analgesia. Furthermore, the subgroup analyses demonstrated that the routes of premedication may not have influenced the superiority of dexmedetomidine over midazolam. Thus, the use of dexmedetomidine can provide additional analgesic benefits for pediatric patients following premedication.

Emergence agitation, which is a frequent phenomenon in children recovering from general anesthesia, creates a challenging situation 64. Various factors, including pain, preoperative anxiety, personal temperament, type of surgical procedure performed and type of anesthetic may contribute to its occurrence 38. Compared with placebo, both dexmedetomidine and midazolam have been shown to reduce EA in children following administration of sevoflurane anesthesia 38. This meta-analysis showed that there was no difference in the incidence of EA between the dexmedetomidine and midazolam groups. Additionally, dexmedetomidine had no overall preventive effect on PONV compared with midazolam. However, no details pertaining to perioperative antiemetic prophylaxis were provided for either group; thus, the evidence supporting this comparison is unclear.

This meta-analysis also compared premedication with dexmedetomidine to placebo. Only two trials focusing on satisfactory intravenous cannulation were included and our analysis was influenced by a high level of heterogeneity. The results of the comparison of dexmedetomidine versus ketamine premedication could not be pooled using meta-analysis due to the limited available data. Ketamine, which may induce adverse cardiostimulatory effects and postoperative delirium, is currently used less frequently as a sole premedicant. Some studies have shown that the combination of ketamine with other drugs for premedication results in satisfactory sedation and a reduction in side effects 65-67. Because this meta-analysis was not designed to explore the combination of different premedicants, these studies were not included.

LimitationsThis meta-analysis had some limitations. First, the sample sizes of all the included trials were relatively small and the methodological quality was variable. Second, differences in age may have influenced some of the results because the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics between younger and older children vary. Third, the various routes of premedication may have also introduced bias. Fourth, significant heterogeneity was observed in some of the analyses (separation from parents, mask induction, HR and SBP before induction, time to discharge from the PACU and satisfactory intravenous cannulation); therefore, the results should be assessed with caution. Fifth, publication bias may have affected the precision of some of the outcomes because positive results are more likely to be published than negative results; hence, our results may have been overestimated. Finally, although considerable clinical data have been reported, dexmedetomidine is not approved for use in children in any country. Thus, its use in children is considered ‘off-label’ and exercising caution in its administration to at-risk patients is warranted.

CONCLUSIONSThis meta-analysis provides evidence that dexmedetomidine is superior to midazolam premedication in promoting preoperative sedation and decreasing postoperative pain. Further studies are needed to evaluate the dosing schemes and long-term outcomes of preoperative dexmedetomidine administration in pediatric anesthesia.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONSPeng K and Wu SR independently searched the following databases up to April 2014: MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL. Any controversy concerning study selection or data extraction was resolved by consensus with Ji FH. Peng K, Wu SR and Ji FH read the full texts of all papers and determined which papers should be included or excluded. Peng K and Wu SR extracted and tabulated all relevant data from the included studies. Validity was assessed and scored by Wu SR and Li J, and checked by Ji FH.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.