It is estimated that up to 65 % of pwMS (people with multiple sclerosis) experience varying degrees of cognitive impairment, the most commonly affected domain being Information Processing Speed (IPS). As sleep disturbance is a predictor of detriments in IPS, the authors aimed to study the association between the severity of Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) and Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) symptoms with IPS in pwMS.

MethodsIn a cross-sectional study, the authors enrolled people with relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive MS referred to the comprehensive MS center of Kashani Hospital in Isfahan, Iran. The authors used Berlin and STOP-Bang questionnaires for assessing OSA symptoms, and the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) scale for the presence and severity of symptoms of RLS. The authors used the Integrated Cognitive Assessment (ICA) test, a language and education-independent tool, to assess visual processing speed.

ResultsThe authors included 211 pwMS, with a mean age of 36.73 ± 8.9 (81.9 % female). PwMS with higher RLS scores showed lower IPS, with ICA indexes of 0.66 ± 0.09 vs. 0.61 ± 0.12 in low- and high-risk RLS groups, respectively (p < 0.01). There were no significant associations between IPS as measured by the ICA index and OSA symptom severity.

ConclusionThe authors found impairments in IPS in pwMS to be linked with the severity of RLS symptoms, but not with OSA. Considering the high prevalence and underdiagnosis of RLS in pwMS, and the profound impact of IPS on quality of life, this association highlights the importance of screening and treating RLS in this population.

Multiple sclerosis, is an immune-mediated neurological disorder. Being the most common non-traumatic disabling disease affecting young adults, it creates a tremendous burden of disease.1 People with MS (pwMS) can experience several disease phenotypes, the most common of which include Relapsing-Remitting MS (RRMS) characterized by acute worsening of symptoms and recovery in between the acute bouts, and secondary progressive MS which is a steady progression of symptoms in a person with an initial relapsing-remitting disease.2

While the typical symptoms of MS were thought to be mostly physical (e.g. optic neuritis, sensory and motor deficits) it is now estimated that about 40 %‒65 % of pwMS experience varying degrees of cognitive impairment.3 Described as the most common symptom of MS, cognitive impairment negatively affects employment, quality of life (to a higher degree compared to physical impairment), social and mental health and has been correlated to increased economic burden.4,5 Such deficits can be observed in the initial stages of the disease, occurring even in the absence of other symptoms. While cognitive impairment is highly variable among individuals, the most commonly affected domains include Information Processing Speed (IPS), learning and memory, with executive function and visuospatial processing impacted at a lower rate.6 IPS, as one of the most frequent impairments observed in pwMS, is suggested to be due to the accumulation of lesions and axonal degeneration over the course of the disease.7 IPS has been suggested to have correlations with fatigue, depression and disease evolution and itself influences psychosocial relationships, social support and clinical variables in pwMS.8

Role of sleep disordersOne of the important variables able to predict detriments in IPS is sleep disturbance.7,9 Associations between sleep and cognitive decline are of interest as they could potentially help in mitigating cognitive decline via improving sleep.10 Importantly, sleep disorders are very common in pwMS, reported by nearly half of the population,11 but regularly underdiagnosed by physicians.12 Among the most common and detrimental of these disorders are Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) (affecting approximately 20 % of the population) and Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) (with a prevalence of up to 58 %).13 Despite the importance of the conditions themselves and their implications for quality of life in pwMS, associations between OSA and RLS and cognitive function in pwMS remains controversial and not extensively studied.14,15

ObjectiveDue to lack of research directly investigating the association between severity of RLS and OSA symptoms with IPS in pwMS, the authors aimed to study this relationship using a practical, language and education independent tool to get a more informed picture of the interplay between sleep disorders and IPS in this population.

Materials and methodsStudy design and inclusion criteriaThis is a cross-sectional study conducted on pwMS referred to comprehensive multiple sclerosis center of Kashani hospital in Isfahan, Iran in 2020‒2021. Study design followed STROBE statement rules and was approved by the Research and Ethics Council of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (ethics code: IR.ARI.MUI.REC.1401.207). Participants were selected and informed on the study aims and protocol. and were enrolled provided having informed consent. Inclusion criteria included: 1) A definite MS diagnosis with RRMS or Secondary Progressive MS (SPMS) phenotypes according to 2017 McDonald's criteria;16 2) Age of 18‒55; 3) No acute relapse in the previous month; 4) No corticosteroid pulse therapy in previous month; 5) No history of other neurological conditions; 6) No history of psychiatric disorders (including major depressive disorder); 7) No history of dementia in first-degree relatives (as per declaration of the participants); 8) Normal visual acuity.

Upon being entered, participants underwent a preliminary interview for gathering their demographic and clinical information followed by a more comprehensive interview aimed at assessing OSA, RLS and information processing speed using the following tests, all of which were conducted by a trained technician.

Measurements and variablesOSABerlin questionnaire17 and STOP-Bang questionnaire18 were used for assessing presence of OSA symptoms and severity. The former is comprised of three categories including snoring, daytime somnolence, and hypertension or BMI. Participants were categorized as low risk if they had no or one positive category and high-risk if two or more categories were positive. The latter uses snoring, tiredness, observed apnea, blood pressure, BMI, neck circumference and gender to categorize patients as low (score of 2 or less), intermediate (score of 3‒4) high-risk (score of 5 or more) for having severe OSA. Notably, STOP-Bang has been shown to be effective in screening for OSA when compared to polysomnography, especially for its moderate and severe forms.19

Restless legs syndromeThe International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) scale20 was utilized for determining presence and severity of symptoms of restless legs syndrome using four criteria including: desire for moving extremities with associated discomfort, motor restlessness aimed to relieve discomfort, symptom relief by activity, worsening of symptoms at nighttime. The scale includes 10 question each being assigned a score between 0 to 4 and the severity is defined as: very severe (score of 31 to 40), severe (score of 21 to 30), moderate (11 to 20), mild (1 to 10) and none (score of 0).

Information processing speedThe authors used Integrated Cognitive Assessment (ICA) test, to assess visual processing speed and accuracy as a proxy for cognitive performance. ICA uses a visual categorization task in which participants are asked to classify natural images as “animal” or “non-animal”. As it is a computer-based test, there is less of a concern with regards to education of the person administering the test (in our study, the test was run on an Apple iPad tablet). Notably, ICA scores have been shown to be correlated with symbol digit modalities test (SDMT) and brief international cognitive assessment in pwMS.21,22 The authors selected 100 images (50 animals and 50 non-animal), each of which were shown for 100 ms, followed by a interstimulus interval of 20 ms, and a noisy mask for 250 ms. Participants were asked to categorize one hundred images as either animal or non-animal and were assigned an index of 0 to 1 based on the ratio of correct answers. ICA score was defined as the probability of normal IPS performance, which was calculated using a supervised regression-based learning algorithm, as the authors have detailed elsewhere.23 The Al engine prediction corresponds with the probability of impairment: a high probability of impairment (above 55 %), results in an “Impaired” prediction; and a low probability of impairment (below 45 %) corresponds with a “healthy” prediction. Borderline cases, between 45 % and 55 % are categorized as “At Risk”. Accuracy is determined by the percentage of images categorized correctly and speed by the fastness of the participant's response reaction time. ICA index represents the combined accuracy and speed of processing scores.21,22

Statistical analysisThe authors compared ICA index and IPS impairment between impaired and non-impaired sleep groups based on STOP-Bang, Berlin, and RLS questionnaires separately. For Berlin test, pwMS with low and high scores were categorized as low- and high-risk. In STOP-Bang test, those with low scores were categorized as low-risk and those with intermediate and high scores as high-risk. This categorization, corresponding to a cut-off score of 3 or higher for high-risk group, has shown high sensitivity in detecting moderate and severe forms of OSA as well as good negative predictive value for OSA in pwMS.24 For IRLSSG, the authors categorized participants with normal and mild scores as low-risk and the rest as high-risk (a categorization frequently used for assessing response to treatment in RLS).25-27 The authors performed an independent samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for numeric variables and a chi-squared test for categorical variables. To compare ICA index between low, intermediate, and high-risk OSA groups based on the STOP -Bang questionnaire, the authors performed a one-way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test for numeric variables and a Chi-Squared test for categorical variables. If there was a significant difference, then the authors performed the post-hoc analysis with the Tukey HSD test. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to evaluate whether variables were normally distributed. Statistical analysis was performed with Python 3.8.5. A significant p-value was defined as less than 0.05.

ResultsParticipant characteristicsThe authors included 211 pwMS, with a mean age of 36.73 ± 8.9 in the study, 81.9 % of whom were female. Participants had a mean EDSS score of 2.40 ± 1.85 with 87.2 % and 12.7 % presenting RRMS and SPMS phenotypes, respectively. All the patients with SPMS had secondary progressive MS. Further demographic and clinical characteristics of participants is shown in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Variable | n = 211 |

|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 36.73 ± 8.9 |

| Education, Educated % (n) | 54.2 (114) |

| Gender Female, % (n) | 81.9 (173) |

| Hand dominance, Right % (n) | 92.6 (188) |

| BMI (Mean ± SD) | 24.50 ± 4.09 |

| Neck circumference (Mean ± SD) | 36.81 ± 3.75 |

| COVID, positive % (n) | 54.5 (115) |

| Addiction, positive % (n) | 9.4 (20) |

| Disease duration (Mean ± SD) | 8.21 ± 6.02 |

| EDSS (Mean ± SD) | 2.40 ± 1.85 |

| Type: RRMS, % (n) | 87.2 (184) |

| Type: SPMS, % (n) | 12.7 (27) |

BMI, Body Mass Index; COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; RRMS, Relapsing Remitting Multiple Sclerosis; SPMS: Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis.

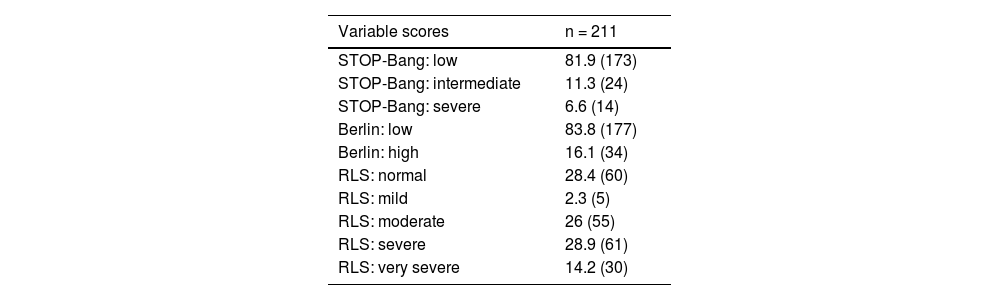

With regards to prevalence of OSA symptoms using STOP-Bang scale, 81.9 %, 11.3 % and 6.6 % of pwMS were categorized as having low, moderate and severe scores, respectively. There were no significant differences in mean ICA index between subgroups, with those in low and high-risk categories having mean scores of 0.62 ± 0.12 and 0.62 ± 0.09, respectively (p = 0.98). On the Berlin scale, 83.8 % and 16.1 % had low- and high-risk scores, respectively. PwMS with low and high OSA risk, according to Berlin scale, did not have significantly different ICA index scores (0.62 ± 0.12 vs. 0.62 ± 0.10; p = 0.92).

RLS and IPSUsing IRLSSG as a measure of RLS symptoms, 28.4 % of patients were defined as normal and the highest proportion reported having severe symptoms with 28.9 % of the participants studied. Patients with low risk IRISSG results had significantly lower mean ICA indexes (0.66 ± 0.09 vs. 0.61 ± 0.12; p < 0.01). The prevalence of symptoms of studied disorders in pwMS is presented in Table 2. ICA indexes according to scale subcategories are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Fig. 1 shows the distribution of ICA index in risk-groups of measures of OSA and RLS.

sleep disorders prevalence in patients with MS.

| Variable scores | n = 211 |

|---|---|

| STOP-Bang: low | 81.9 (173) |

| STOP-Bang: intermediate | 11.3 (24) |

| STOP-Bang: severe | 6.6 (14) |

| Berlin: low | 83.8 (177) |

| Berlin: high | 16.1 (34) |

| RLS: normal | 28.4 (60) |

| RLS: mild | 2.3 (5) |

| RLS: moderate | 26 (55) |

| RLS: severe | 28.9 (61) |

| RLS: very severe | 14.2 (30) |

RLS, Restless Legs Syndrome.

Despite the high prevalence and disability levels caused by cognitive impairment in pwMS, most studies have focused on such impairment more generally and there has been less focus on specific domains. In this present investigation, attempting to make the relationship between sleep disorders and cognitive difficulties clearer in pwMS, the authors studied measures of OSA, RLS and IPS in this population. The authors did not observe a significant relationship between the measures of OSA and IPS, but wedid find a significant association between RLS and IPS as measured by ICA index. To our knowledge, this is the first study of this relationship using ICA. A test that unlike more traditional measures of cognitive functions such as SDMT, is not dependent on language and education, and is more practical due to its shorter duration, independence from operator skill and computer-based administration,21 as well as its ability in detecting IPS even in early stages of cognitive impairment in pwMS.23

OSA has been known to have a higher prevalence in pwMS28 and has been associated with cognitive impairment in this population.9 Due to differences in study populations and designs, estimates vary greatly when it comes to the prevalence, ranging from 0 %‒58 %.29,30 Similar variation is also observable in studies using STOP-Bang for finding high risk individuals. Sunter et al. noted a 24.7 % prevalence of increased risk for OSA by STOP-Bang questionnaire,31 and rates of up to 46 % have been reported as well.32,33 The authors found 17.9 % and 16.1 % of the participants to have elevated risk for OSA according to STOP-Bang and Berlin scales (showing the reliability of both scales in measuring OSA risk in pwMS), which is slightly lower than those of the aforementioned studies and could be due to higher predominance of women and relatively low BMI in the participants (as presented in Tables 4 and 5). The authors utilized these OSA scales due to their cost-effectiveness, especially considering their effectiveness in comparison with polysomnography.19 OSA has been shown to cause cognitive impairment,34,35 an observation which has also been replicated in pwMS suffering from the condition as well.9 Similar dysfunctions have also been noted with regards to IPS. In a review article, Kilpinen et al. reported half of the studies to show reduced IPS in patients with OSA,36 however, there is a lack of investigations dedicated to IPS in pwMS. The authors did not find a difference in IPS (as measured by ICA index) in those at low and high risks for OSA; and indeed, the relationship between cognitive impairment and OSA remains controversial in pwMS. While Barley et al. detected a significant association between OSA and cognitive impairment in pwMS9 (and IPS more specifically), McNicholas et al. did not observe such a correlation and noted the likelihood of potential comorbid OSA as a contributing factor in studies finding said associations. Importantly, in the latter study, participants were treated for OSA and verbal learning was indeed observed to improve after interventions, however, no such improvements were seen with measures of IPS.14 This lack of improvement in IPS despite receiving OSA treatment, taken together with the present findings, could suggest that IPS may not be mediated by OSA in pwMS. However, Considering the implications of this relationship, it is important to note that in the present analysis, the authors have not taken potential disease- and patient-related factors (such as the effects of medication and comorbidities related to OSA) into account. It could be that longitudinal studies taking a more comprehensive approach with regards to variables studied would find different results. Unfortunately, most studies have investigated cognitive impairment more generally, as opposed to focusing on objective measures of one specific domain, which makes comparing and generalizing interpretations of the present results challenging. While the authors do believe that our observation is an important addition to the literature on the relationship between OSA and IPS in pwMS, there is a clear need for more investigation in this area. Overall, it seems that the cognitive impairment observed in pwMS with comorbid OSA is likely to be observed in domains other than IPS.

RLS is another sleep disorder with higher prevalence among pwMS than general population, with estimates including a wide range of 13.3 %‒65.1 %.37 The authors found a rather high prevalence of RLS symptoms in the studied population, with 69.2 % of the cohort showing moderate, severe and very severe symptoms of RLS, as measured by IRLSSG. The authors observed a significantly poorer performance in IPS as measured by ICA index. The present results support those reported by Cederberg et al. who investigated the relationship between the prevalence and severity of RLS and perceived cognitive impairment in adults and noted a positive relationship. However, as noted by authors, the self-report nature of cognitive impairment was a limiting factor in the study; moreover, cognitive impairment was measured using a global scale rather.38 In a further study, Cederberg et al. explored the relationship between symptoms of RLS and objective measures of cognitive function in 22 adults with MS and RLS, concluding an association between severity of RLS symptoms and a number of different domains of cognitive impairment, including IPS.15 The present study design means that the authors now have evidence, using objective and domain specific measurement in a large sample size, for the relationship between RLS and impairment in IPS in pwMS. To our knowledge, no study on has been conducted on whether interventions for treating RLS does indeed reduce cognitive impairment and IPS in pwMS. Due to potential for reducing disability, this is an especially important question to answer, considering the high prevalence observed among pwMS as well as the high rate of its underdiagnosis in this population.39,40

The present results, indicating a positive relationship between RLS and IPS in pwMS needs to be regarded with the limitations in mind. First of all, as we aimed to examine correlation between symptoms of sleep disorders and IPS, the authors did not use a definite diagnosis of sleep disorders included (i.e., using polysomnography for a diagnosis of OSA and the diagnostic criteria of RLS); this means the study is limited as the mere presence of these symptom, despite their severity, cannot be equated with presence of the diseases themselves. Secondly, the high prevalence of severe OSA and RLS symptoms could make it hard to generalize the present results. Another limitation regards the lack of data on genetic variance of the apolipoprotein ε4 allele and its potential confounding role, considering its potential effect on development of both OSA and cognitive dysfunction.41 Moreover, the authors were limited in the assessment of family history of dementia in the participants as we relied only on the participant's statements on whether they had any family history of dementia. While the authors did discuss symptoms of dementia and allowed time for them to consult with their family members regarding the matter, this remains a limitation for the present study; especially as it is likely that some of the first-degree relatives did not live long enough to develop dementia. Furthermore, the authors were also limited by a cross-sectional design and using samples from a single institution, making us unable to draw any causal conclusions. This points to the need for further, multi-center longitudinal studies to make the controversial associations between sleep disorder and cognitive impairment, more generally, and IPS, more specifically, in pwMS clearer.

ConclusionThe authors found impairments in IPS in pwMS to be linked with severity of RLS symptoms, but not with OSA. Considering the high prevalence and underdiagnosis of RLS in pwMS, and the profound impact of IPS on quality of life, this association highlights the importance of screening and treating RLS in this population.

CRediT authorship contribution statementFereshteh Ashtari: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Arshia Ghalamkari: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Saba Naghavi: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Ahmad Pourmohammadi: Software, Formal analysis, Visualization. Iman Adibi: Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Zahra Karimi: Investigation, Software, Formal analysis. Aryan Kavosh: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation.

This study was funded by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.