A circumscribed lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum (SCC) is a rare finding, and little is known about its etiology.1 Reversible splenial lesions in the CC are observed in various diseases (Table 1).1–33

Etiologies of isolated reversible lesions in the splenium of the corpus callosum

| Etiology | # of pts | Pathophysiology (vasogenic/cytotoxic edema) |

|---|---|---|

| Encephalitis/Encephalopathy/Cerebellitis2–12 | 30 | Intramyelinic, cytotoxic edema, inflammatory infiltrate |

| Antiepileptic drug usage or withdrawal13–18 | 24 | vasogenic/cytotoxic edema |

| Epilepsy1,12,19–21 | 20 | vasogenic edema |

| High-altitude illness22 | 7 | vasogenic edema |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus23,24 | 4 | nm |

| Methyl bromide poisoning25 | 2 | nm |

| Malnutrition26,27 | 2 | probable vasogenic edema |

| Hypoperfusion due to metabolic changes28,29 | 1 | probable focal cytotoxic edema |

| Hemolytic-uremic syndrome30 | 1 | vasogenic edema |

| Charcot-Marie-Tooth31 | 1 | nm |

| Aseptic meningitis32 | 1 | cytotoxic edema |

| Aseptic meningomyelitis (present case) | 1 | cytotoxic edema |

pts: patients; #: number; nm: not mentioned.

The combination of aseptic meningitis or meningomyelitis and acute urinary retention has been recently acknowledged and, in the absence of accompanying abnormalities, has been referred to as meningitis-retention syndrome (MRS) by some Japanese authors.34,35 Only a few reports of MRS are available to date.34–38 Although the term meningitis was used, some of the reported cases could in fact have been myelitis in view of the presence of fecal incontinence and brisk reflexes.34

To the best of our knowledge, the combination of neurogenic bladder and reversible splenial lesion due to meningomyelitis or to any other condition has not been reported previously. Here, we report a case of an isolated reversible splenial lesion and a neurogenic bladder in a woman with aseptic meningomyelitis.

CASE HISTORYA 26-year-old female was admitted to a local hospital with symptoms of acute fever, headache, phonophobia, photophobia, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, appetite loss, and fatigue. She was administered oral cefuroxime axetil and 0.9% intravenous saline for two days, with a diagnosis of dehydration and acute sinusitis. She took the antibiotic for two days. She was then evaluated by another clinician due to suspicion of meningitis based on marked neck stiffness and a positive Kernig’s sign, and was administered Procaine penicillin for one day and cefazolin for four days. Because of persistent fever, she was referred to our hospital. On admission, her complaints were only headache and fatigue, and she presented a fever of 39.5°C. Her physical examination revealed no distinct findings or any definite signs of meningeal irritation or mucocutaneous lesions. She was alert, fully conscious, and was well oriented. Her sensation, including the perineal area, was normal. She demonstrated no signs of encephalopathy. Her neurological examination showed only right truncal and gait ataxia. She presented no seizure or head trauma, and she was not taking any antiepileptic drugs.

Laboratory examination revealed normal C-reactive protein, with a normal white blood cell count but a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (40 mm/h). The only laboratory test performed before she was accepted to our hospital was urinalysis, which revealed a density of 1030. The blood chemistry, urinalysis, and immunoglobulin concentrations (G, A, and M) were normal. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed a mononuclear leukocytosis of 408/mm3, increased protein content of 165 mg/dl, and a mildly decreased glucose level of 38 mg/dl (34% of serum glucose). Bacterial smears and cultures, including tuberculosis, were negative. No increase in oligoclonal bands and a mild increase in the IgG index (0.8) were observed in the CSF. The CSF enzyme immunoassay demonstrated negative IgM antibodies against herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) and herpes varicella zoster (VZV) viruses. Neither tuberculosis nor HSV was detected in her CSF sample by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Furthermore, brucella agglutination was negative in the CSF.

Serological tests on the blood samples – brucella agglutination, salmonella agglutination, brucella Coombs, and VDRL – were negative. Western blot examination revealed that the samples were negative for IgM and IgG antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi and IgM antibodies against HSV-1. Anti-ds DNA, Ena Jo-1, Ena SCL70, Ena Sm, Ena Sm-RNP, Ena SsA, Ena SsB, anti-cardiolipin, and anti-phospholipid antibodies were also negative. The lipid profile, fibrinogen, homocysteine, antithrombin III, and protein C and S levels were all within normal ranges.

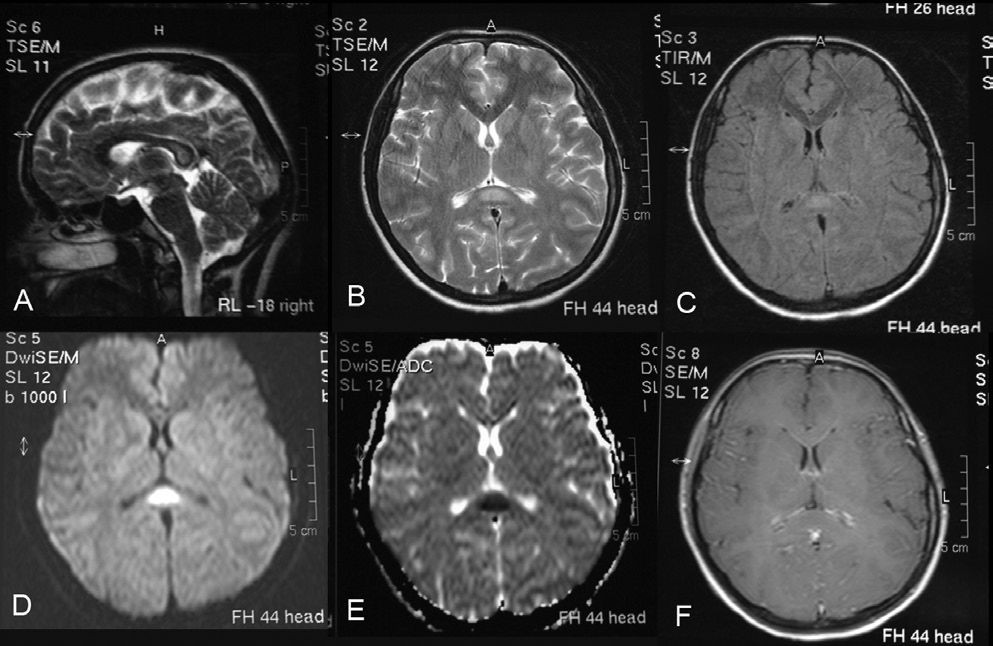

Electroencephalography (EEG), echocardiography, and abdominal and urinary ultrasonography were normal. Cranial magnetic resonance images (MRI) on admission demonstrated an isolated small lesion in the SCC that was markedly hyperintense on diffusion-weighted images (DWI), fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images, and T2-weighted images (T2WI); hypointense on the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and slightly hypointense on T1-weighted images (T1WI) (Figure 1). Some increase was observed only in the enhancement of the leptomeninges (Figure 1A).

Sagittal T2-weighted image (a), transverse T2-weighted image (b), transverse FLAIR image (c), and diffusion-weighted image (d) showing a high-intensity signal in the splenium of the corpus callosum. Transverse apparent diffusion coefficient image (e) showing a low-intensity signal in the splenium of the corpus callosum. Contrast transverse T1-weighted image showing only some slight contrast enhancement of the leptomeninges (f)

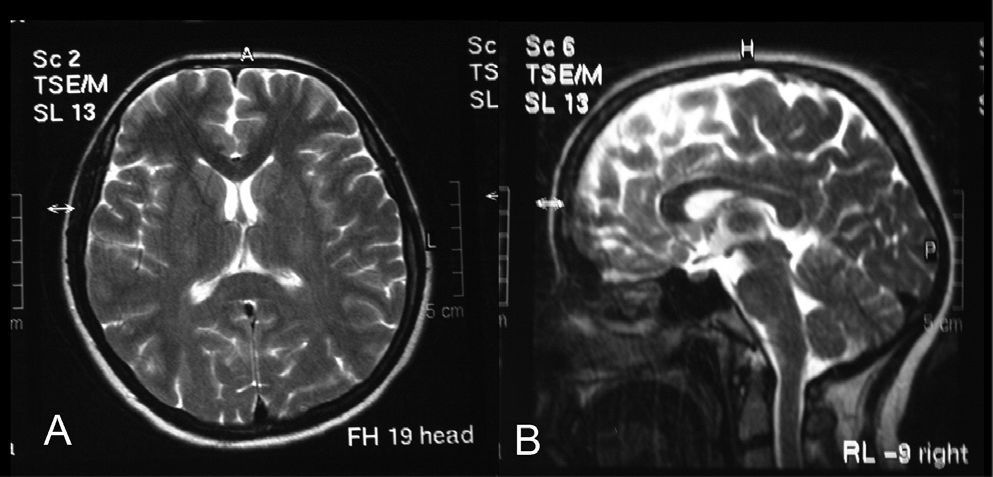

Four days later, the patient developed lower abdominal pain and one episode of fecal incontinence. The urinary bladder was distended and palpable above the symphysis pubis. Catheterization of the urinary bladder yielded some clear urine. An urodynamic study revealed an acontractile neurogenic bladder, but bladder sensation was spared with a first urge to void after 129 ml of 0,9% intravesically saline was given. No other neurological abnormalities were detected. Spinal cord MRI revealed that the cervical and thoracic spinal cord was swollen. T2WI showed diffuse high-signal intensity inside the cervical and thoracic spinal cord (Figure 2A). The pia mater over the cervical spinal cord, the thoracic spinal cord, and the parenchyma were enhanced heterogeneously, whereas diffuse meningeal enhancement was present over the conus medullaris (Figure 2B, 2C).

Non-contrast T2-weighted image showing a diffuse high-signal intensity inside the cervical and thoracic spinal cord (a). Contrast sagittal T1-weighted image showing diffuse meningeal enhancement over the conus medullaris (b). The parenchyma was enhanced heterogeneously on the contrast T1-weighted image (c)

Based on the CSF findings, ceftriaxone and acyclovir treatment were started for an initial diagnosis of aseptic meningitis or poorly treated bacterial meningitis. After five days of treatment, the patient was still febrile. Ampicillin was added to the treatment for suspected meningitis due to Listeria monocytogenes. After three days of ampicillin treatment, her fever resolved. Ceftriaxone and acyclovir treatment was continued for fourteen days, and ampicillin treatment for twenty-one days.

In order to ameliorate the voiding difficulty, a permanent internal catheter was implanted for six weeks. Ten days later, her fever had diminished. On follow-up five weeks after the initial examination, gait ataxia and cranial and spinal MRI findings had resolved (Figures 3 and 4); at seven weeks, the urodynamic study was normal.

In clinical practice, it is rare to find only a focal nonhemorrhagic lesion within the central portion of the SCC.23 In our patient, it is probable that the posterior CC (splenial) lesion, which is an important cause of dysarthria and gait ataxia4,6,13 and which had resolved in five weeks, was due to aseptic meningomyelitis. This condition might have been associated with an overlooked mild metabolic encephalopathy. Although cranial MR findings in our patient suggested that the lesion was ischemic in nature (because of the decreased ADC values), we did not consider ischemia as the causative factor.5,26 Furthermore, lesions marked by abnormal signal intensity arising from infarctions are usually irreversible.26 However, as observed in our patient, the splenial lesion and gait ataxia can resolve completely.

In 2004, Tada et al. reported clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy in fifteen patients with reversible splenial lesions on MRI. In ten of those fifteen patients (67%), the pathogen was not clarified, as in our patient.5 A tendency towards the splenium seems to be apparent in various forms of encephalitis/encephalopathy. It has been suggested that this could be due to: 1) high density of drug and toxin receptors of splenium, which may make it sensitive to vasogenic edema,23 and 2) participation of elevated inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6, which may be responsible for the intramyelinic edema or inflammatory infiltrate.2,3 Although our patient did not have obvious encephalopathy, second mechanism could also have been responsible for her condition.

The patterns of reversible splenial damage are not specific for a certain disease, but they may be regarded as characteristic of groups of lesions. Differential diagnosis depends on the clinical course and laboratory findings observed for the patients.2 Therefore, the most common etiologic factors in reversible lesions of the splenium were excluded from the diagnosis of our patient. We considered that her reversible splenial lesion was mediated by aseptic meningomyelitis.

Splenial lesions could be interpreted as a consequence of a multifactorial pathological process.1 For example, if MR examination is not performed for patients with systemic infections associated with encephalopathy/encephalitis, minor asymptomatic splenial lesions could be overlooked.2 This holds true for our patient, as we would not have detected the splenial lesion if we had not performed cranial MRI in order to exclude cerebellitis.

Focal lesions in the SCC are thought to be a non-specific endpoint of different disease processes leading to vasogenic or cytotoxic edema. Because posterior CC damage is known to be an important cause of dysarthria and gait ataxia,4,6,13,23 patients with meningomyelitis should also be carefully investigated through the use of cranial MRI, including DWI/ADC, followed by repeated MRIs in order to determine whether the splenial lesion (causing gait ataxia) is transient.23 As observed in our patient, the gait ataxia resolved in conjunction with the disappearance of the splenial lesion.

Our patient not only demonstrated a reversible lesion in the SCC, but also reversible acute urinary retention, which is a symptom of urological emergency.34 The neurogenic bladder observed in our patient was similar to that observed in HSV type 2-induced lumbosacral meningoradiculitis, known as Elsberg syndrome or MRS.39 To the best of our knowledge, splenial lesions have not been detected or mentioned in patients with MRS (Table 2).34,36,38–49

Cranial MRI findings in patients with neurogenic bladder due to meningitis-retention syndrome

| Reference | # of pts | Illness | Pathogen | Splenial lesion in MRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kawamura, 200739 | 1 | Aseptic meningitis | Probably HSV-6 | nm |

| Bollen, 200740 | 1 | Meningoradiculitis | HSV-2 | nm |

| Furugen, 200641 | 1 | Eosinophilic meningoencephalitis | A. cantonensis | nm |

| Sakakibara, 200534 | 3 | Aseptic Menengitis | - | none |

| Yoritaka, 200542 | 4 | Radiculoneuropathy | HSV-2 and other HSV-types | nm |

| Zenda, 200236 | 1 | Aseptic meningitis | - | none |

| Urakawa, 200143 | 1 | Aseptic meningitis | - | none |

| Kanazawa, 200044 | 1 | Aseptic meningitis | - | nm |

| Shimizu, 199945,reviewed in34 | 2 | Aseptic meningitis | - | 1-nm |

| 1-none | ||||

| Jensenius, 199746 | 1 | Aseptic meningitis | HSV- 2 | nm |

| Fukagai, 1996reviewed in34 | 1 | Aseptic meningitis | - | nm |

| Vonk, 199347 | 2 | Sacral myeloradiculitis | HSV-2 | nm |

| Lepori, 199248 | 1 | Aseptic meningitis | HSV-2 | nm |

| Steinberg, 199138 | 1 | Aseptic meningitis | HSV | nm |

| Ohe, 1990reviewed in34 | 1 | Aseptic meningitis | - | none |

| Hemrika, 198649 | 3 | Sacral myeloradiculitis | HSV-2 | nm |

| Kano, 1985reviewed in34 | 1 | Aseptic meningitis | - | nm |

| Present case | 1 | Aseptic meningomyelitis | - | + |

An underactive detrusor muscle is regarded to be the major cause of voiding dysfunction in neurological diseases, and it originates from various lesion sites in the neural axis.34,50 In our patient, an upper motor neuron lesion that affected the spinal cord could have caused an underactive detrusor. Although upper motor neuron involvement was suggested in MRS (combination of acute urinary retention and aseptic meningitis), to date only three cases (four cases including the present case) displayed symptoms suggestive of myelitis.34 We thus suggest that it would be better to describe the condition as meningomyelitis-retention-syndrome (MMRS) instead of MRS. In our patient, myelitis was confirmed by MR findings and fecal incontinence.

MRS has been suggested to be a mild variant of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), which is regarded to have a parainfectious or an autoimmune origin.34 Although MRS (or the more correct MMRS) has been reported to follow a benign and self-remitting course (duration of two to ten weeks), urgent management of the acute urinary retention is necessary.34,36 Immediate treatment by internal catheterization of our patient resulted in complete recovery in seven weeks.

The incidence of encephalitis/encephalopathy or meningomyelitis with reversible splenial lesion might be higher than previously thought. However, whenever gait ataxia occurs during the course of meningitis or encephalitis/encephalopathy, it should be kept in mind that, in addition to the myelitis, the ataxia could be due to a reversible splenial lesion, as splenial lesions can cause severe gait ataxia.23

The presence of a neurogenic bladder should also be kept in mind when dealing with a patient with meningomyelitis. Although a rare condition, it is a very serious manifestation of aseptic meningomyelitis and should be promptly treated in order to avoid over-distension bladder injury.36

In conclusion, mild gait ataxia and acute urinary retention can occur during the course of aseptic meningomyelitis, secondary to splenial lesion and myelitis, respectively. Acute urinary retention should be treated immediately to avoid irreversible damage.