General surgeons dealing with laparoscopic herniorrhaphy should be aware of the aberrant obturator artery that crosses the superior pubic ramus and is susceptible to injuries during dissection of the Bogros space and mesh stapling onto Cooper’s ligament. The obturator artery is usually described as a branch of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery, although variations have been reported.

MATERIALS AND METHODSThe present study was conducted on 98 pelvic halves of embalmed cadavers, and the origin and course of the obturator artery were traced and noted.

RESULTSIn 79% of the specimens, the obturator artery was a branch of the internal iliac artery. It branched off at different levels either from the anterior division or posterior division, individually or with other named branches. In 19% of the cases, the obturator artery branched off from the external iliac artery as a separate branch or with the inferior epigastric artery. However, in the remaining 2% of the specimens, both the internal and the external iliac arteries branched to form an anastomotic structure within the pelvic cavity.

CONCLUSIONThe data obtained in this study show that it is more common to find an abnormal obturator artery than was reported previously, and this observation has implications for pelvic surgeons and is of academic interest to anatomists. Surgeons dealing with direct, indirect, femoral, or obturator hernias need to be aware of these variations and their close proximity to the femoral ring.

A severe and potentially lethal complication in pelvic injuries is arterial bleeding commonly involving the branches of the internal iliac artery, namely, the lateral sacral, iliolumbar, obturator, vesical, and inferior gluteal arteries.1 A sound knowledge of retropubic pelvic vascular anatomy is pivotal for successful performance of endoscopic total extraperitoneal inguinal hernioplasty,2 as well as for laparoscopic herniorrhaphy. The trans-abdominal approach is an approach to hernia repair that is unfamiliar to most general surgeons. The ideal reconstruction of the floor of the inguinal canal during a herniorrhaphy involves good anatomic dissection and exposure,3 which can only be accomplished by entering the subinguinal space of Bogros. There is adequate anecdotal experience to indicate that the relationships of structures near the internal ring are not generally well known, and this may predispose them to injury during surgery.4 Surgeons must be conscious of unexpected sources of hemorrhage, such as an aberrant obturator artery or vein, and unexpected iliopubic vessels and take appropriate precautions to avoid injury to these structures. Regarding the variability in the origin of the OA, Bergman et al. documented that it may arise from the common iliac or anterior division of the internal iliac in 41.4% of cases, from the inferior epigastric in 25% of cases, from the superior gluteal in 10% of cases, from the inferior gluteal/internal pudendal trunk in 10% of cases, from the inferior gluteal in 4.7% of cases, and from the internal pudendal in 3.8% of cases.5 The human cadaver is probably an ideal model to explore the surgical anatomy. This study was conducted with the objective of evaluating the incidence of normal and aberrant origins of the obturator artery and to describe their relevance in surgical practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODSNinety-eight formalin-fixed human hemi-pelvises (62 male and 36 female) were dissected in the pelvic and retropubic inguinal region. The branches of the internal and external iliac artery were dissected. The obturator artery was identified and traced from its origin to its exit at the obturator membrane. The course of the artery and its relation to the surrounding structures were noted. Photographs were taken to document the variations.

RESULTSThe results are tabulated in table 1.

In 79% (77/98 specimens) of the specimens, the obturator artery branched from the internal iliac artery either at its anterior or posterior division. In the majority of these (59/77) specimens, the obturator artery was a branch of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery, and in the other 18 specimens, it was a branch of the posterior division (Table 2).

The different types of origin of the obturator artery from the external and internal iliac artery

| Artery | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal iliac: (n=77) | Anterior division | 34 (44%) | 25 (33%) |

| Posterior divisionSeparate branch | 5 (6%) | 2 (3%) | |

| With Superior gluteal | 7 (9%) | 3 (4%) | |

| With Iliolumbar | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| External iliac: (n= 19) | Separate branch | 4 (21%) | 1 (5%) |

| With inferior epigastric | 9 (47%) | 5 (26%) |

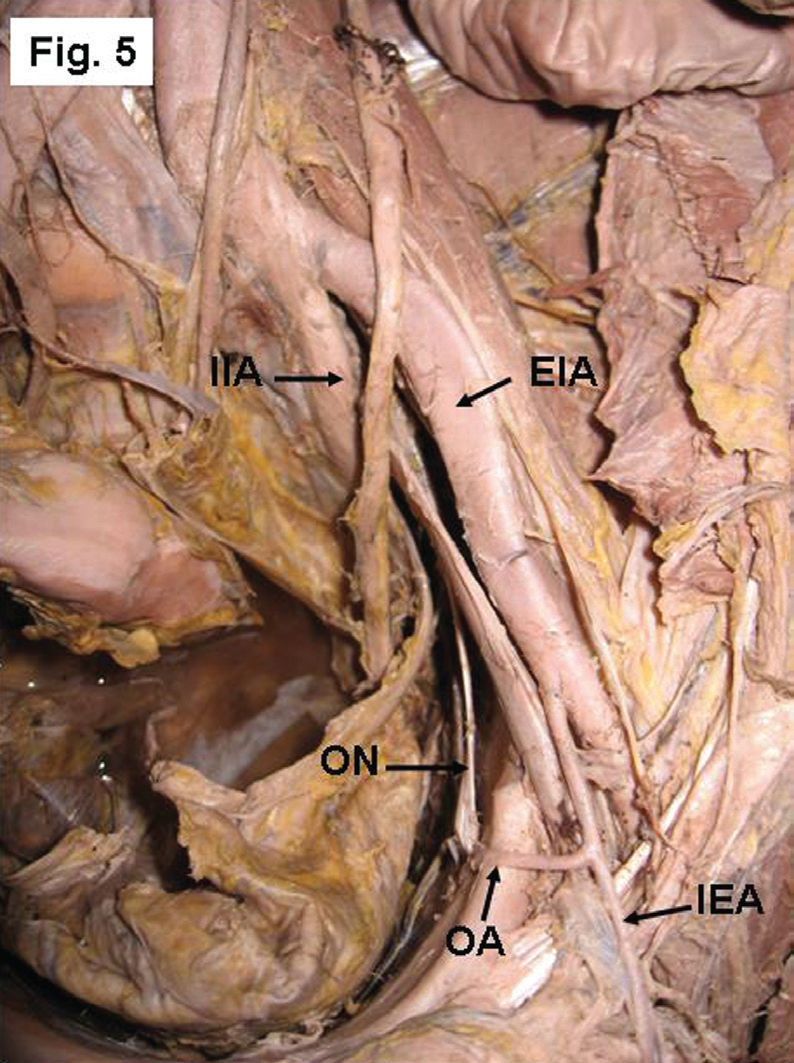

The obturator artery originated individually (Fig. 1) or with the iliolumbar (Fig. 2) or the superior gluteal branch (Fig. 3) of the posterior division of the internal iliac artery. In 19% (19/98) of the specimens, the obturator artery branched from the external iliac artery as a separate branch (Fig. 4) or with the inferior epigastric artery (Fig. 5). However, in the remaining 2% (2/98) of specimens, the obturator artery branched from both the internal and the external iliac arteries. The obturator artery (OA1) that branched from the external iliac artery crossed the superior pubic ramus and advanced towards the obturator foramen, although before entering the foramen it anastomosed with the narrow branch (OA2) arising from the internal iliac artery (Fig. 6). In all cases in which the obturator artery branched from the external iliac artery, the branch crossed the external iliac vein anteriorly and then the superior pubic ramus. It then proceeded downward to enter the obturator foramen, where it was accompanied by the obturator vein and the obturator nerve. However, in one hemi-pelvis, the obturator artery, as a branch of the external iliac artery, was observed to course posterior to the external iliac vein and then to follow the course described above (Fig. 7). We also noticed that in most of the specimens, the superior pubic ramus was crossed by venous structures that varied in number and size and coursed from the obturator foramen to the inguinal region to drain into the external iliac vein.

The most common source of origin of the obturator artery is as a single branch arising from the anterior division of the internal iliac artery. However, the literature contains many articles that report variable origins. Interesting variations in the origin and course of the principal arteries have long attracted the attention of anatomists and surgeons. The embryological explanations for the anomalies in the arterial patterns of the limbs are based on an unusual selection of channels from a primary capillary plexus, wherein the most appropriate channels enlarge while others retract and disappear, thereby establishing the final arterial pattern.6,7 The OA arises comparatively late in development as a supply to a plexus, which in turn is joined by the axial artery of the lower limb that accompanies the sciatic nerve.8 The origin of the OA from the posterior division of internal iliac artery [IIA] is due to the persistence of vascular channels in relation to the posterior division that might have given rise to the OA, while the vascular channels related to the anterior division of the internal iliac artery destined for the OA have disappeared.9 Before the obturator artery appears as an independent blood vessel from the 'rete pelvicum’, the blood flow destined for this territory makes an unusual choice of source channels. Instead of arising from the internal iliac artery as usually occurs, it arises from the inferior epigastric artery or directly from the external iliac artery. The presence of a dual origin of the obturator artery may be interpreted as due to the two source channels for the blood flow, one from the internal iliac artery and the other from the inferior epigastric artery.8

In the present study, the most common origin of the OA in both males and females was from the internal iliac artery (Table 1), more often from the anterior division (Table 2) and in a few cases from the posterior division as a separate branch or with a common origin with the superior gluteal/iliolumbar artery. Bergman et al.5 reported that the OA is a branch of the common iliac or anterior division of the internal iliac artery [IIA] in 41.4% of cases and arises from the superior gluteal artery in 10% of cases. The parietal branches of the OA are important collaterals in aortoiliac and femoral arterial occlusive diseases. In cases of ischemic necrosis of the head of the femur following decreased blood flow through the OA, a possible bypass graft may be considered to connect the posterior division to the distal end of the obstruction. Moreover, the increased length of the OA, due to its origin from the posterior division of the internal iliac, may present an additional advantage while grafting.9

In the present study, no obturator arteries were found to arise from the common iliac artery; however, in 19% of the total limbs studied, it originated from the external iliac artery. This study documents the percentage of obturator arteries arising directly from the external iliac artery as 21% in males and 5% in females. The origination of the obturator artery directly from the external iliac artery was reported as 1.1% by Bergman et al.,5 25% by Missankov et al.,10 and 1.3% by Jakubowicz and Czerniawska-Grzesinska.11 Bergman et al. further documented that the existence of a common origin of the inferior epigastric and obturator arteries is a relatively frequent variation that occurs in 20–30% of cases, whereas Jakubowicz and Czerniawska-Grzesinska11 reported the occurrence in only 2.6% of cases. The present study, however, reports a higher incidence of this variation: 47% in males and 26% in females.

In cases of ligation of the internal iliac arteries and their branches in women undergoing pelvic surgery, as well as in cases of obstruction of the internal iliac artery due to any cause, the OA and its branches will be spared, especially the branch to the head of femur, when the obturator artery arises from the external iliac artery. The existence of a dual origin for the obturator artery is a more unusual anomaly that occurs at a frequency of 1%, 12 whereas in the present study, a dual origin was found in 2 cases (6%), which is a slightly higher incidence than that previously observed.

The “corona mortis” is an anatomical variant, an anastomosis between the obturator and the external iliac or inferior epigastric arteries or veins, located on the superior pubic ramus. It is significant because hemorrhage may occur if the corona mortis is accidentally cut and achievement of subsequent hemostasis is difficult. Orthopedic surgeons planning an anterior approach to the acetabulum, such as the ilioinguinal or the intrapelvic approach (modified Stoppa), must be cautious when dissecting near the superior pubic ramus.13 However, Darmanis et al13 also state that, despite the high prevalence of these large retropubic vessels in the operating room, surgeons should exercise caution but not alter their surgical approach for fear of excessive hemorrhage. Tracing along the aberrant vessel can easily identify the obturator foramen, which is an anatomic landmark that indicates an adequate inferior dissection of the preperitoneal space.2 The need to map these vessels is becoming more crucial as surgeons choose various approaches to the space of Bogros and insert a synthetic mesh that requires anchoring during herniorrhaphies.3