Hürthle cell carcinoma (HCC) is an uncommon thyroid cancer historically considered to be a variant of follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC). The aim of this study was to assess the differences between these groups in terms of clinical factors and prognoses.

Patients and methodsA total of 230 patients (153 with FTC and 77 with HCC) with a median follow-up of 13.4 years were studied. The different characteristics were compared using SPSS version 20 statistical software.

ResultsPatients with HCC were older (57.3±13.8 years versus 44.6±15.2 years; p<0.001). More advanced TNM stages were also seen in patients with HCC and a greater trend to distant metastases were also seen in patients with HCC (7.8% versus 2.7%, p=0.078). The persistence/recurrence rate at the end of follow-up was higher in patients with HCC (13% versus 3.9%, p=0.011). However, in a multivariate analysis, only age (hazard ratio [HR] 1.10, confidence interval [CI] 1.04–1.17; p=0.001), size (HR 1.43, CI 1.05–1.94; p=0.021), and histological subtype (HR 9.79, CI 2.35–40.81; p=0.002), but not presence of HCC, were significantly associated to prognosis.

ConclusionHCC is diagnosed in older patients and in more advanced stages as compared to FTC. However, when age, size, and histological subtype are similar, disease-free survival is also similar in both groups.

El carcinoma de células de Hürthle (CCH) es un tipo de cáncer de tiroides infrecuente considerado históricamente una variante del carcinoma folicular de tiroides (CFT). El objetivo de este estudio fue conocer las diferencias que existen entre estos grupos en cuanto a los factores clínicos y pronósticos.

Pacientes y métodosSe incluyeron 230 pacientes (153 CFT y 77 CCH) con un seguimiento mediano de 13,4 años. Se compararon las diferentes características utilizando el programa estadístico SPSS versión 20.

ResultadosLos pacientes con CCH tenían mayor edad (57,3±13,8 años vs. 44,6±15,2 años; p<0,001). También se observaron estadios TNM más avanzados en los CCH, con una mayor tendencia a presentar metástasis a distancia (7,8% vs. 2,7%; p=0,078). El porcentaje de persistencia/recurrencia al finalizar el seguimiento del estudio fue mayor entre los pacientes con CCH (13% vs. 3,9%; p=0,011). Sin embargo, en el análisis multivariante, solo la edad (hazard ratio [HR]: 1,10; intervalo de confianza [IC]: 1,04-1,17; p=0,001), el tamaño (HR: 1,43; IC: 1,05-1,94; p=0,021) y el subtipo histológico (HR: 9,79; IC: 2,35-40,81; p=0,002) se asociaron de forma significativa con el pronóstico, pero no el presentar un CCH.

ConclusiónEl CCH se diagnostica en pacientes de mayor edad y en estadios más avanzados que el CFT. Sin embargo, si la edad, el tamaño y el subtipo histológico son similares, la supervivencia libre de enfermedad no difiere en ambos grupos.

Thyroid cancer is the most common endocrine neoplasm and accounts for 1% of all tumors. Differentiated thyroid carcinoma or differentiated follicular line carcinoma, which includes papillary carcinoma and follicular carcinoma, accounts for over 90% of all thyroid gland neoplasms.1

Follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC) is the second most frequent thyroid cancer, after papillary carcinoma, representing 10–15% of all thyroid carcinomas in iodine-sufficient areas.2,3 It is a malignant epithelial tumor with evidence of follicular differentiation, but lacks the nuclear features that characterize papillary carcinoma (i.e., a large pale nucleus, the absence of a nucleolus, and the presence of notches and pseudoinclusions). Follicular thyroid carcinoma is more common in women, and the mean age at the time of diagnosis is 45–55 years (older than in other differentiated thyroid carcinomas).

Two histopathological categories have been established for the effects of prognosis: minimally invasive and extensively invasive follicular carcinoma.4 The minimally invasive subtype is characterized by a complete capsule with microscopic capsular or vascular invasion foci (<4 foci), while the extensively invasive variant presents more than four foci corresponding to vascular and/or capsular invasion and/or extrathyroid spread.5 The extensively invasive presentations can infiltrate adjacent tissues, though regional lymph node involvement is rare, since spread is usually via the hematogenous route.6

Hürthle cell carcinoma (HCC) accounts for 3% of all thyroid gland tumors.7,8 Hürthle cells are large polygonal cells derived from the thyroid follicular epithelium, and exhibit an eosinophilic granular cytoplasm due to the presence of abundant mitochondria, a large nucleus, and a prominent nucleolus. These cells can be observed in both benign and malignant thyroid gland disease. The diagnosis of HCC is defined by the presence of a nodule with the characteristics of FTC, a prevalence of Hürthle cells (at least 75% of all the cells) and capsular and/or vascular invasion. These tumors can also be classified as minimally invasive or extensively invasive.5

The latest thyroid tumor classification of the World Health Organization (WHO) of 2017 defines HCC as an independent type of thyroid carcinoma, whereas it had previously been regarded as a variant of FTC.5,9 Recent studies suggest that HCC has clinical features that differentiate it from FTC. These tumors are characterized by a certain male predominance; the patients are older on average; and in some studies the tumor size is greater.10–14 Furthermore, recent molecular studies also suggest that HCC is different from FTC.15,16 With regard to the prognosis, HCC has been considered more aggressive than FTC, among other reasons due to a higher incidence of distant metastases at the time of diagnosis.12,14 However, doubts have been raised concerning the extent to which this is due to the diagnosis of HCC at older ages than other differentiated thyroid carcinomas, the higher male frequency, and the presentation of the disease in more advanced stages.

In the same way as in FTC, the treatment of patients with HCC comprises surgery with ablative I131 therapy. However, there is controversy regarding the usefulness of I131 treatment in HCC, since iodine uptake appears to be lower than in the other differentiated thyroid carcinomas. Most studies that have evaluated this aspect are retrospective in design and involve small patient samples. Recent studies suggest that I131 treatment improves the survival of these patients, and its use is therefore recommended by the clinical guides.12,16

The present study was carried out to assess the clinical, histological and prognostic differences between FTC and HCC. An analysis was also made of disease-free survival in tumors of this kind, and of the factors associated with a poorer prognosis.

Material and methodsThe study included all patients diagnosed with FTC (including HCC) between 1987 and 2015 and operated upon in the Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra (Navarra, Spain), with follow-up for at least 5 years at this center. Total thyroidectomy was performed in all cases, in one or two surgical steps. A total of 97.3% of the patients (n=224) received complementary therapy with I131.

Tumor histology was evaluated by pathologists experienced in thyroid gland disease. The diagnosis of malignancy was based on the presence of extracapsular disease spread or vascular invasion. The HCC group included those tumors in which over 75% of the cells were oncocytic or Hürthle cells (eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, hyperchromatic nucleus and prominent nucleolus). Carcinomas in which over 50% of the cells were poorly differentiated and anaplastic were discarded. Multifocal tumors where a neoplasm different from FTC conditioned the diagnosis were also excluded. Oncocytic variant papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) was likewise not included in the study.

The patient case histories were reviewed. The primary study variable or endpoint was the presence of persistent tumor or disease recurrence at the end of the study or at the time of patient death. The presence of disease required confirmation by histological or cytological study. Other clinical variables such as patient age and gender, tumor size, and the treatment provided were also analyzed.

The histological characteristics of the tumors were established by pathologists. Minimally invasive tumors were defined as those with fewer than four capsular invasion foci and no extrathyroid spread, or fewer than four vascular invasion foci. By contrast, extensively invasive tumors were defined by more than four foci corresponding to vascular and/or capsular invasion and/or extrathyroid spread. Tumor stage was assessed based on the 7th edition of the TNM classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), and was established at the time of the diagnosis.17 The TNM stage was not available in three patients, while the histological subtype was not available in two patients.

All patients were controlled at our center at least once a year. Follow-up involved the compilation of the case history, physical examination, and the determination of thyroglobulin and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies. Periodic neck ultrasound explorations were also made, and imaging tests were requested (X-rays, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography), according to clinical suspicion. As indicated by the guides, we performed stimulated thyroglobulin determination with body scans to detect persistent/recurrent disease. The absence of disease was defined by stimulated thyroglobulin <1ng/ml in the absence of anti-thyroglobulin antibodies, a negative body scan, and the absence of suspect adenopathies in the neck ultrasound exploration.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were reported as the mean±standard deviation, and the Student's t-test was used for the comparison of such variables. Categorical variables were reported as numbers and percentages, and comparisons were made using the chi-squared test. The comparison of disease-free survival between the different groups was based on the plotting of Kaplan–Meier curves and the log-rank test. The Cox regression model was used to analyze the prognostic factors associated with tumor persistence/recurrence. Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05.

Data analysis was performed using the SPSS version 20.0 statistical package.

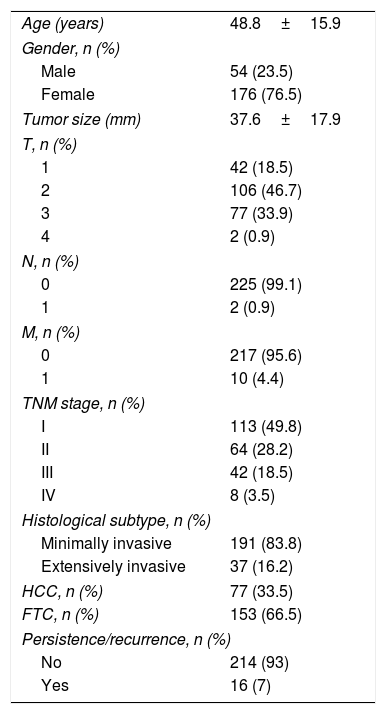

ResultsThe study included a total of 230 patients, of which 77 presented HCC. The median duration of follow-up was 13.4 years. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of all the patients in the sample. The mean patient age was 48.8±15.9 years, and women were seen to predominate (76.5%). The mean tumor size was almost 4cm (37.6±17.9mm). Only 0.9% (n=2) of the patients presented adenopathies at diagnosis, and 4.4% (n=10) had distant metastatic spread.

Baseline characteristics of the study sample.

| Age (years) | 48.8±15.9 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 54 (23.5) |

| Female | 176 (76.5) |

| Tumor size (mm) | 37.6±17.9 |

| T, n (%) | |

| 1 | 42 (18.5) |

| 2 | 106 (46.7) |

| 3 | 77 (33.9) |

| 4 | 2 (0.9) |

| N, n (%) | |

| 0 | 225 (99.1) |

| 1 | 2 (0.9) |

| M, n (%) | |

| 0 | 217 (95.6) |

| 1 | 10 (4.4) |

| TNM stage, n (%) | |

| I | 113 (49.8) |

| II | 64 (28.2) |

| III | 42 (18.5) |

| IV | 8 (3.5) |

| Histological subtype, n (%) | |

| Minimally invasive | 191 (83.8) |

| Extensively invasive | 37 (16.2) |

| HCC, n (%) | 77 (33.5) |

| FTC, n (%) | 153 (66.5) |

| Persistence/recurrence, n (%) | |

| No | 214 (93) |

| Yes | 16 (7) |

Quantitative variables are reported as the mean±standard deviation, and qualitative variables as numbers and percentages.

HCC: Hürthle cell carcinoma; FTC: follicular thyroid carcinoma.

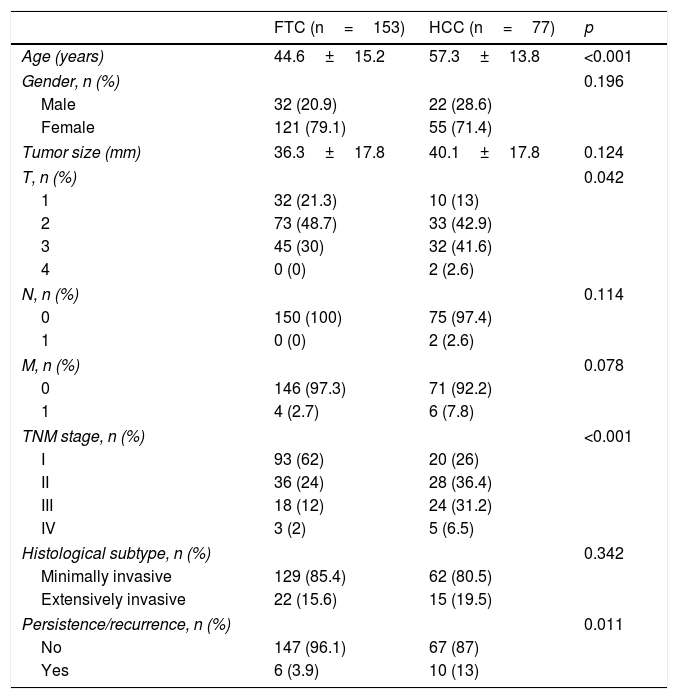

Table 2 compares the characteristics of the patients with FTC and HCC. The patients with HCC were older on average (57.3±13.8 years versus 44.6±15.2 years; p<0.001). We also recorded more advanced TNM stages in the patients with HCC, with a greater tendency to present distant metastases (7.8% versus 2.7%; p=0.078). Furthermore, the only two patients with adenopathies in the neck lymph node chains corresponded to HCC cases. Although the HCC group was characterized by a greater presence of males, a larger tumor size, and more frequent extensively invasive tumors, the differences were not statistically significant. However, at the end of the study, percentage persistence/recurrence was greater among the patients with HCC (13% versus 3.9%; p=0.011).

Comparison of patients with FTC and HCC.

| FTC (n=153) | HCC (n=77) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.6±15.2 | 57.3±13.8 | <0.001 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.196 | ||

| Male | 32 (20.9) | 22 (28.6) | |

| Female | 121 (79.1) | 55 (71.4) | |

| Tumor size (mm) | 36.3±17.8 | 40.1±17.8 | 0.124 |

| T, n (%) | 0.042 | ||

| 1 | 32 (21.3) | 10 (13) | |

| 2 | 73 (48.7) | 33 (42.9) | |

| 3 | 45 (30) | 32 (41.6) | |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 2 (2.6) | |

| N, n (%) | 0.114 | ||

| 0 | 150 (100) | 75 (97.4) | |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 2 (2.6) | |

| M, n (%) | 0.078 | ||

| 0 | 146 (97.3) | 71 (92.2) | |

| 1 | 4 (2.7) | 6 (7.8) | |

| TNM stage, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| I | 93 (62) | 20 (26) | |

| II | 36 (24) | 28 (36.4) | |

| III | 18 (12) | 24 (31.2) | |

| IV | 3 (2) | 5 (6.5) | |

| Histological subtype, n (%) | 0.342 | ||

| Minimally invasive | 129 (85.4) | 62 (80.5) | |

| Extensively invasive | 22 (15.6) | 15 (19.5) | |

| Persistence/recurrence, n (%) | 0.011 | ||

| No | 147 (96.1) | 67 (87) | |

| Yes | 6 (3.9) | 10 (13) | |

Quantitative variables are reported as the mean±standard deviation, and qualitative variables as numbers and percentages.

HCC: Hürthle cell carcinoma; FTC: follicular thyroid carcinoma.

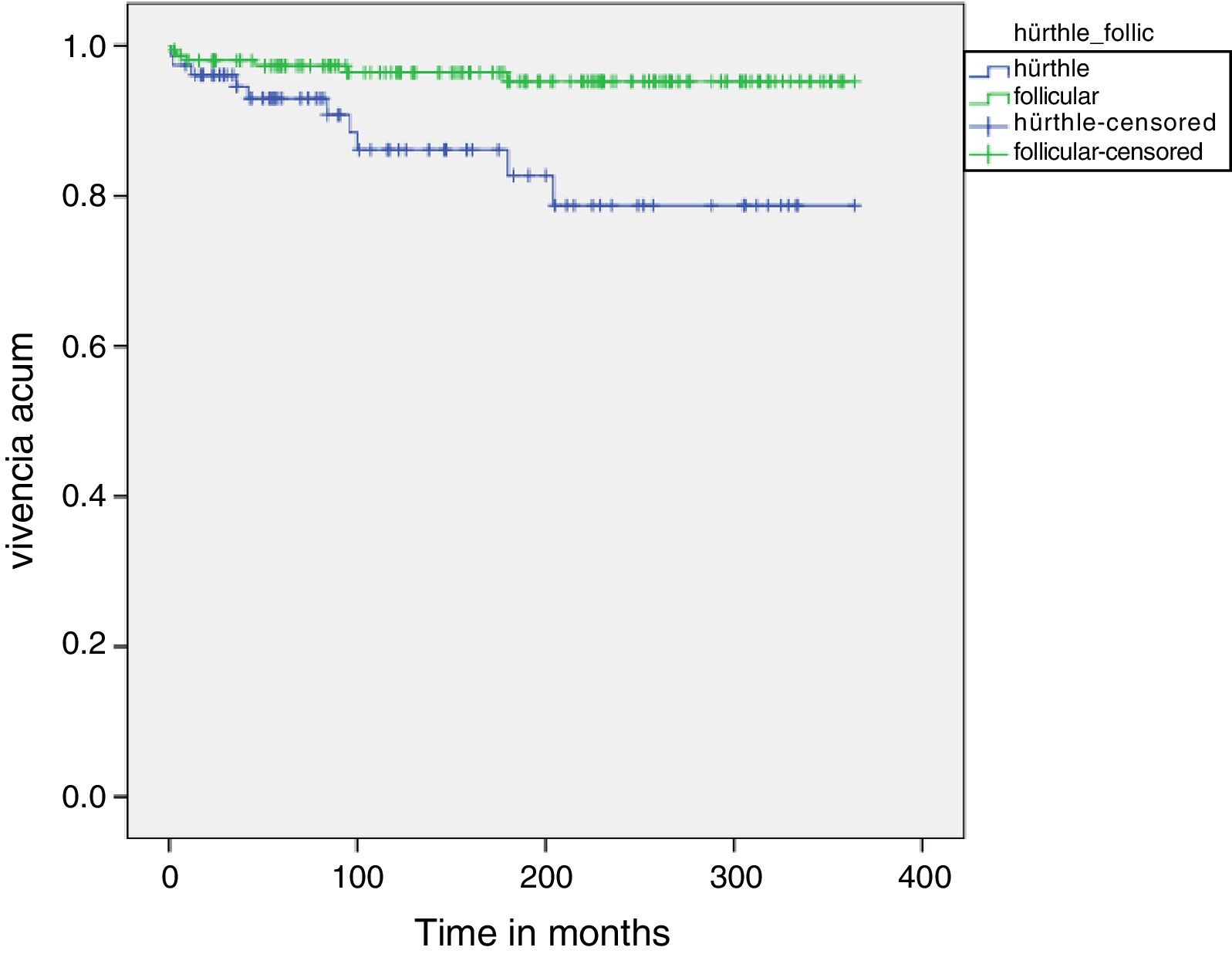

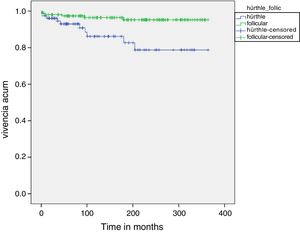

Fig. 1 shows the disease-free survival curves corresponding to both tumor types. The disease-free survival rate in the HCC group was 92.9%, 86.1% and 78.7% after 5, 10 and 20 years, respectively, versus 97.3%, 96.4% and 95.2% in the FTC group. These differences were statistically significant (p=0.003).

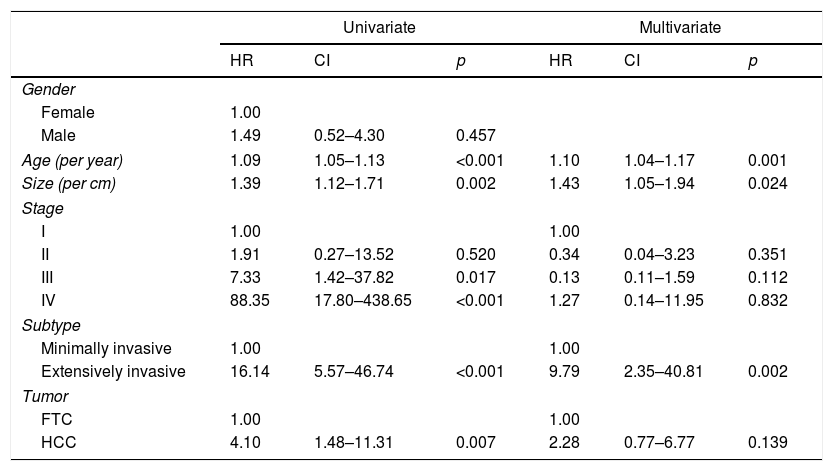

Table 3 shows the results of the regression analysis made to determine the factors associated with poorer patient prognosis. In the univariate analysis, patient age, tumor size, TNM stage, histological subtype and HCC were associated with a poorer prognosis. However, after adjusting for the different factors, the multivariate analysis only identified age (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.10; confidence interval [CI]: 1.04–1.17; p=0.001), tumor size (HR: 1.43; CI: 1.05–1.94; p=0.021) and histological subtype (HR: 9.79; CI: 2.35–40.81; p=0.002) as exhibiting a statistically significant association.

Factors associated with poorer prognosis in the study population.

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | CI | p | HR | CI | p | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1.00 | |||||

| Male | 1.49 | 0.52–4.30 | 0.457 | |||

| Age (per year) | 1.09 | 1.05–1.13 | <0.001 | 1.10 | 1.04–1.17 | 0.001 |

| Size (per cm) | 1.39 | 1.12–1.71 | 0.002 | 1.43 | 1.05–1.94 | 0.024 |

| Stage | ||||||

| I | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| II | 1.91 | 0.27–13.52 | 0.520 | 0.34 | 0.04–3.23 | 0.351 |

| III | 7.33 | 1.42–37.82 | 0.017 | 0.13 | 0.11–1.59 | 0.112 |

| IV | 88.35 | 17.80–438.65 | <0.001 | 1.27 | 0.14–11.95 | 0.832 |

| Subtype | ||||||

| Minimally invasive | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Extensively invasive | 16.14 | 5.57–46.74 | <0.001 | 9.79 | 2.35–40.81 | 0.002 |

| Tumor | ||||||

| FTC | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| HCC | 4.10 | 1.48–11.31 | 0.007 | 2.28 | 0.77–6.77 | 0.139 |

HCC: Hürthle cell carcinoma; FTC: follicular thyroid carcinoma; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Hürthle cell carcinoma (HCC) accounts for 3% of all thyroid gland cancers and historically has been regarded as a FTC subtype.5 However, recent studies have questioned whether HCC truly represents a variant of FTC, and propose that it actually constitutes a distinct disease entity with a different mutational profile and a clinical behavior different from that of FTC.15 For this reason, the latest WHO classification of 2017 considers HCC to be an independent subtype within the context of differentiated thyroid carcinoma.7

Differences between follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC) and Hürthle cell carcinoma (HCC)In the present study we found HCC to manifest in older individuals than in the case of FTC; in more advanced stages of the disease; and with a greater tendency toward persistence or recurrence over follow-up. Tumor size, male prevalence and the frequency of extensively invasive tumors were also greater, though the differences were not statistically significant.

Comparable findings have been reported in other studies with a similar design. Goffredo et al.13 compared 3311 patients with HCC and 59,585 subjects with other types of differentiated thyroid carcinoma (including PTC and FTC), drawn from a large cancer registry. As in our study, the authors observed important differences in terms of age. The mean age of the patients with HCC in the publication of Goffredo et al. was 57.6 years, versus 48.9 years in the other differentiated carcinoma group. The authors recorded differences in relation to tumor size (36.1±22.1mm in HCC and 20.1±17.8mm in the other differentiated thyroid carcinomas; p<0.001). In our series, tumor size was greater in the HCC group, though the differences were not statistically significant. This may be because Goffredo et al. included PTCs, which are more frequent and generally smaller at the time of diagnosis than FTC.

Haigh and Urbach10 analyzed the differences between 172 patients with HCC and 673 patients with FTC. Hürthle cell carcinoma was characterized by a greater proportion of patients over 50 years of age (61% in HCC versus 55% in FTC; p<0.001) and a greater presence of males (39% in HCC versus 28% in FTC; p=0.005), though no significant differences were observed in terms of tumor size, lymph node infiltration or distant metastatic spread. The frequency of lymph node infiltration and distant spread in HCC and FTC was greater than in our series (distant metastases 15% and lymph node infiltration 5% for HCC, versus 10% and 3%, respectively, for FTC).

A recent study published by Kim et al.18 also sought to analyze the differences between these two types of tumors. The authors studied 80 patients with HCC and 483 with FTC, and observed difference in mean age between the two groups, though the patients were younger than in our own series. As in our observations, males were more numerous in the HCC group than in the FTC group, though the difference likewise failed to reach statistical significance (22.5% in HCC versus 15.5% in FTC). Tumor size was very similar in the two groups (35mm for FTC versus 34mm for HCC). The authors recorded lymph node infiltration in only 15 FTCs, and in contrast to our own observations, distant metastasis was more frequent in the FTC group (8% versus 3% in the HCC group). This is one of the few studies to also analyze the frequency of minimally and extensively invasive tumors in the two groups, as in our study. The authors recorded a similar incidence of extensively invasive tumors in the two groups (30% in HCC versus 28% in FTC). Our own results were similar, though of lesser magnitude (19.5% in HCC versus 15.6% in FTC).

Factors associated with disease-free survivalIn our series, disease-free survival in the HCC group was 92.9% after 5 years, 86.1% after 10 years, and 78.7% after 20 years. In comparison, disease-free survival in the FTC group was significantly greater (97.3% after 5 years, 96.4% after 10 years, and 95.2% after 20 years). In a recent study, Oluic et al.19 analyzed the behavior of HCC and recorded a disease-free survival rate after 5, 10 and 20 years of 91.1%, 86.2% and 68.5%, respectively. This study comprised 239 patients with HCC that were treated and followed-up at the same center. These data are very similar to our own.

However, our intention was to establish whether HCC has a poorer prognosis than FTC per se, or whether the observations are due to the fact that the frequency of other risk factors is greater in HCC, since very few studies have examined this issue. Other studies have reported a greater incidence of different factors in HCC, some of which have been associated with a poorer prognosis in thyroid cancer. We, therefore, performed a Cox regression analysis to determine which factors are associated with poorer disease-free survival. According to our results, the factors which correlated to poorer disease-free survival were patient age, tumor size and the extensively invasive histological subtype. In this regard, it can be affirmed that although HCC patients have a poorer disease-free survival, this is not a consequence of the tumor but of other factors. Patients with HCC are older and the tumors also tend to be larger and more often of an extensively invasive nature, although these differences were not found to be statistically significant in our series. Therefore, a patient with HCC and a patient with FTC of the same age, with the same tumor size and the same histological subtype can expect similar disease-free survival.

This finding is similar to that reported by Haigh and Urbach.10 In the univariate analysis, a patient age of over 50 years, gender, tumor size, extrathyroid disease spread, adenopathies, distant metastasis and the presence of HCC were associated with poorer disease-free survival. However, after adjusting for the different factors in the multivariate analysis, only a patient age of over 50 years, tumor size, the presence of adenopathies and metastasis were seen to be associated with a poorer prognosis. The survival curves of the patients with HCC and FTC were seen to be very similar after adjusting for the different factors. This led the authors to conclude that the prognosis of both types of tumor was similar, and that similar treatment measures were indicated.

LimitationsOur study has certain limitations. Firstly, it was a retrospective study with a long patient inclusion period; as a result, the clinical and histopathological data were not available for all the patients.

Furthermore, as these were patients from a single center, it is difficult to draw general conclusions, though we believe that the findings can be applied to other similar populations. The fact that the patients were from a single center made data collection more homogeneous, and information loss was not as great as it would have been in a multicenter study.

ConclusionIn summary, FTC and HCC have different clinical characteristics in relation to presentation, such as patient age and TNM stage, since HCC is diagnosed in older individuals compared with FTC. This causes HCC to be associated with a greater probability of disease persistence/recurrence compared with FTC. However, after analyzing these two types of tumors, we found the factors associated with prognosis to be patient age, tumor size and the histological subtype, rather than the fact of the tumor type being HCC. Consequently, the fact that the type of tumor is HCC does not imply a poorer prognosis if patient age and histological subtype are the same as in a patient with FTC.

Conflicts of interestNone.

The authors thank all the members of the Department of Endocrinology and Nutrition of the Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra for their collaboration.

Please cite this article as: Ernaga Lorea A, Migueliz Bermejo I, Anda Apiñániz E, Pineda Arribas J, Toni García M, Martínez de Esteban JP, et al. Comparación de las características clínicas en pacientes con carcinoma folicular de tiroides y carcinoma de células de Hürthle. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2018;65:136–142.