To assess glycemic control in diabetic patients, to measure the impact on such control of adherence to hypoglycemic agents and to medical visits, and to explore factors that allow for predicting adherence.

MethodsStudy of historical cohorts of diabetic patients. The proportion of patients who achieved the target HbA1c levels was estimated. Adherence was assessed using the Haynes-Sackett test. Change in HbA1c from the first to the last visit, adherence, and attendance to visits were analyzed according to comorbidities, cardiovascular risk factors, and treatments used.

ResultsThe study simple consisted of 639 patients (mean follow-up time, 11.1±11.2 months), of whom 66.6% achieved target HbA1c levels. Change in HbA1c from the first to the last visit was explained in 54.2% of patients by baseline HbA1c (p<0.001), in 13% by treatment adherence (p<0.001), and in 9.6% by visit adherence (p<0.001). Non-insulinization (p=0.011) and smoking cessation (p=0.032) predisposed to greater adherence. Insulinization (p=0.019) and lack of diabetes education (p=0.033) predisposed to visit non-compliance.

ConclusionsImprovement in HbA1c is determined by baseline HbA1c, treatment adherence, and attendance to visits. Patients on insulin have poorer adherence and are more likely to miss the appointments, those who stop smoking adhere more to hypoglycemic agents, and those given therapeutic education are more likely to keep the appointments.

Valorar el control glucémico de pacientes diabéticos, medir la influencia en este control de la adherencia a los hipoglucemiantes y a las visitas médicas, y explorar factores que permitan predecir esta adherencia.

MétodosEstudio de cohortes históricas de pacientes diabéticos. Se midió el porcentaje que alcanzó una HbA1c dentro del objetivo. Se valoró la adherencia mediante la pregunta de Haynes-Sacket. Se estudiaron el cambio en la HbA1c entre la primera y la última visita, la adherencia y la asistencia a las consultas en función de las comorbilidades, los factores de riesgo cardiovascular y los tratamientos utilizados.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 639 pacientes (tiempo medio de seguimiento 11,1±11,2 meses). El 66,6% alcanzó una HbA1c dentro del objetivo. El cambio en la HbA1c entre la primera y última visita se explicó en un 54,2% por la HbA1c inicial (p<0,001), en un 13% por la adherencia terapéutica (p<0,001) y en un 9,6% por la adherencia a las citas (p<0,001). La no insulinización (p=0,011) y el cese del tabaco (p=0,032) predispusieron a una mayor adherencia. La insulinización (p=0,019) y la falta de educación terapéutica (p=0,033) predispusieron a no acudir a las visitas.

ConclusionesLa mejora de la HbA1c está determinada por la HbA1c inicial, la adherencia terapéutica y la asistencia a las citas. Los insulinizados tienen peor adherencia y faltan más a la consulta, los que dejan de fumar se adhieren más a los hipoglucemiantes y los que reciben educación terapéutica acuden más a la consulta.

The COst of Diabetes in Europe–Type 2 (CODE-2) study1 showed that in 2002 only 31% of European patients with diabetes achieved adequate blood glucose control, defined as HbA1c≤6.5%. The more recently published PANORAMA study2 assessed the degree of blood glucose control of 5817 diabetic patients enrolled in 2010 in nine European countries; 37.4% of these patients were found to have HbA1c values >7% (poor metabolic control). These data suggest that glucose control may be improving throughout Europe, as in other regions of the world,3 and lead us to ask about the factors that continue to cause lack of blood glucose control in many patients.

The factors that most increase the probability of having HbA1c values outside the target range (>7%), according to the PANORAMA study,2 are young age (for each additional year, the probability of poor blood glucose control decreases by 2%), diabetes duration (for each additional year, the probability of poor control increases by 2%), poor adherence to medication and lifestyle (these multiply the risk of poor control by 3.98 and 2.16 respectively), and treatment complexity (the greater the complexity, the poorer the control). Other studies have suggested that clinical inertia, i.e., lack of therapy adjustment by physicians in uncontrolled patients, may also contribute to inadequate blood glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.4

Among these factors, lack of treatment adherence is particularly relevant because of its modifiable nature and its serious consequences (it increases the risk of diabetic complications, hospitalization,5 and healthcare expenses6). Because of this, more intensive research has been conducted in recent years on the causes of this lack of treatment adherence in patients with high cardiovascular risk. The Fixed-dose Combination Drug for Secondary Cardiovascular Prevention-1 (FOCUS-1) study,7 which assessed adherence to statins, aspirin, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors in patients with acute myocardial infarction in the past two years, showed that treatment non-adherence affects 45% of these patients and is related to use of multiple drugs, age (the younger the age, the lower the adherence) and presence of depression. In the CDC Canarias study,8 48% of men and 28% of women with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) were found to be non-adherent. In another follow-up study with different oral hypoglycemic agents, adherence after 12 months was 60% for metformin, 56% for sulfonylureas, and 48% for repaglinide.9 In a cohort of 151,173 diabetic patients seen in Quebec (Canada),10 greater adherence to oral hypoglycemic agents was detected in patients with older ages, living in rural areas, with low or medium socioeconomic status beneficiaries of a reduced co-payment, with their first hypoglycemic agent prescribed by general practitioners as compared to endocrinologists or internists (greater adherence in less complex patients), with a history of use of five or more drugs before starting this first hypoglycemic agent, and with less than seven visits to their physician during the first year of treatment.

Published research on blood glucose control and treatment adherence in T2DM has some limitations. First, since the patient cohort of the PANORAMA study was recruited, new drug treatment options have emerged in these patients, including as linagliptin, saxagliptin, alogliptin, lixisenatide, weekly exenatide, dulaglutide, albiglutide, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, canagliflozin, and degludec, and data comparing the adherence to each of these new hypoglycemic agents are not available. Second, some factors with potential influence on treatment adherence, such as family history of diabetes, have not been considered yet.

This study was intended to assess the current blood glucose control of patients with T2DM followed up at an endocrinology clinic, to measure the impact on this degree of adherence to hypoglycemic agents and medical visits, and to explore the factors that predict for treatment adherence.

MethodsStudy design. Inclusion and exclusion criteriaA historical cohort study was conducted. The inclusion criteria were patients over 18 years of age of both sexes diagnosed with T2DM and attending at the endocrinology clinic of Hospital Dr. José Molina Orosa (Lanzarote) from September 2011 to July 2016. Patients with T2DM from penitentiary facilities and obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery were excluded. Patients followed up at the clinic gave their informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital.

Data collectionThe medical records of patients meeting the inclusion criteria were reviewed. Variables analyzed included:

- -

Sex, age, diabetes duration, and family history of diabetes

- -

Comorbidities. Percentages of patients with diabetic retinopathy, cataracts, chronic kidney disease, diabetic neuropathy, coronary heart disease, arrhythmia, stroke, peripheral artery disease, dental disease, mental illness (treated with anxiolytics, antidepressants, hypnotics), hypothyroidism, and use of gastric protectors.

- -

Metabolic parameters and cardiovascular risk factors. The values recorded at the first visit and the last visit were compared, and the change in each parameter was calculated:

- •

Body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and blood pressure (BP). BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

- •

HbA1c and percentage of patients with hypoglycemia. The proportion of patients who achieved HbA1c values within the range (<7.5% for those over 70 years, with more than 10 years of diabetes, or macroangiopathies, <7% in all other patients) in the last visit was determined.

- •

Total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides.

- •

Percentage of smokers and patients with smoking cessation.

- -

Follow-up indicators. Attendance to appointments, follow-up time, and number of visits.

- -

Treatments used. Hypoglycemic agents, therapeutic education, and physical exercise. The daily number of drugs per patient was quantified. It was assessed whether hypoglycemic, antihypertensive, and lipid-lowering drugs had been adjusted during follow-up, classifying patients into one of three categories for each drug class: no change, dose adjustment, drug change or addition. Adherence to hypoglycemic agents was assessed by asking each patient the Haynes-Sackett question: “Most patients have difficulty taking all their tablets, do you have difficulty taking all yours?”. This method is validated in our population and has shown a high positive predictive value and acceptable specificity.11

Change in HbA1c between the first and last visit, treatment adherence, and attendance to visits were studied as a function of demographic characteristics, comorbidities, associated cardiovascular risk factors, follow-up indicators, and treatments used. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables as percentages. For normally distributed samples, a Student's t test was used for hypothesis tests with continuous variables, or an ANOVA test if more than two groups were compared. When variables were not normally distributed, a Mann–Whitney test was used, or a Kruskal–Wallis test if more than 2 groups were compared. For hypothesis tests with proportions, a Chi-squared test was used. Correlation between quantitative variables was calculated using Pearson or Spearman coefficients depending on whether they were normally distributed or not. Once all these comparisons were made, the results obtained were submitted to the corresponding multivariate analyses: change in HbA1c was studied using a linear regression technique, while treatment adherence and attendance to visits were assessed using a multinomial regression technique. Statistical data analysis was performed using SPSS® version 21.0 software (Chicago, IL, USA). A two-sided significance level of p<0.05 was used for all tests.

ResultsPatients enrolled. Baseline characteristicsA total of 639 patients were enrolled. Mean follow-up time at the clinic was 11.1±11.2 months, and mean number of visits was 3±2.4. Fifty patients (7.8%) died during follow-up.

Baseline characteristics of patients were: mean age, 62±11.5 years; mean diabetes duration, 11.7±9.5 years; proportion of women, 52.6%; proportion with family history of diabetes, 74.5%; BMI, 32.3±6.9kg/m2; waist circumference, 105.9±13.2cm; HbA1c, 8.6±1.7%; systolic BP, 140.9±21.1mmHg; diastolic BP, 80.7±12.6mmHg; LDL, 113±37.9mg/dL; HDL, 47.1±14.5mg/dL; triglycerides, 178.1±135.9mg/dL; and smokers, 15.4%.

Prevalence rates of comorbidities were as follows: diabetic retinopathy not photocoagulated, 18.5%; photocoagulated, 14%; treated with intravitreal agents, 1.4%; treated with intravitreal agents; cataract, 24.5%; chronic kidney disease stage 3, 17.4%; stage 4, 1.7%; stage 5, 0.3% (1.6% required dialysis and 0.5% kidney transplant); diabetic neuropathy, 33.7%; coronary heart disease, 18.3%; atrial fibrillation, 4.9%; other arrhythmia, 2.2%; stroke, 7.4%; peripheral artery disease, 17.7%; amputation, 2.5%; any dental disease, 89.3%; use of anxiolytics, 9.9%; use of antidepressants, 11.7%; use of hypnotics, 9.7%; hypothyroidism, 16.6%; and use of gastric protectors, 58.5%.

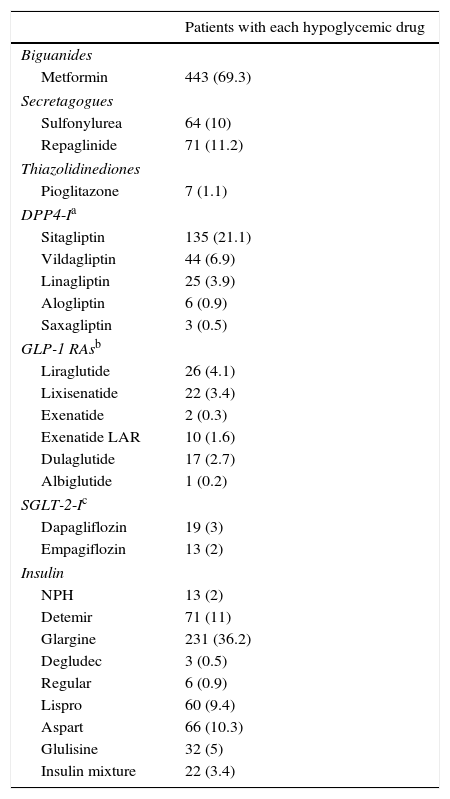

Treatments usedTherapeutic education was provided to 62.9% of patients, and 54.7% performed physical exercise. Smoking cessation counseling was given to smokers, and smoking cessation was achieved in 25% of them. Average daily number of drugs per patient was 8.6±4.1. Hypoglycemic regimens were used in the following proportions: monotherapy, 17.9%; dual therapy, 18.2%; triple therapy, 7.8%; basal insulin, 24.6%; basal-bolus insulin, 25.5%; and insulin mixture, 3%. The hypoglycemic agents used are shown in Table 1. Hypoglycemic doses were titrated during follow-up in 15.8% of patients, and hypoglycemic agents were added or replaced by others in 59.1%. Inertia occurred with hypoglycemic agents in 2.3% of cases.

Hypoglycemic drugs used.

| Patients with each hypoglycemic drug | |

|---|---|

| Biguanides | |

| Metformin | 443 (69.3) |

| Secretagogues | |

| Sulfonylurea | 64 (10) |

| Repaglinide | 71 (11.2) |

| Thiazolidinediones | |

| Pioglitazone | 7 (1.1) |

| DPP4-Ia | |

| Sitagliptin | 135 (21.1) |

| Vildagliptin | 44 (6.9) |

| Linagliptin | 25 (3.9) |

| Alogliptin | 6 (0.9) |

| Saxagliptin | 3 (0.5) |

| GLP-1 RAsb | |

| Liraglutide | 26 (4.1) |

| Lixisenatide | 22 (3.4) |

| Exenatide | 2 (0.3) |

| Exenatide LAR | 10 (1.6) |

| Dulaglutide | 17 (2.7) |

| Albiglutide | 1 (0.2) |

| SGLT-2-Ic | |

| Dapagliflozin | 19 (3) |

| Empagiflozin | 13 (2) |

| Insulin | |

| NPH | 13 (2) |

| Detemir | 71 (11) |

| Glargine | 231 (36.2) |

| Degludec | 3 (0.5) |

| Regular | 6 (0.9) |

| Lispro | 60 (9.4) |

| Aspart | 66 (10.3) |

| Glulisine | 32 (5) |

| Insulin mixture | 22 (3.4) |

Data are given as n (%).

Target HbA1c levels were achieved by 66.6% of patients at the end of follow-up, and 14.1% of patients had hypoglycemic episodes. Mean change in HbA1c between the first and last visit was −1.2±1.7. Change in HbA1c correlated with age (rho=0.162; p=0.001) and with baseline values of HbA1c (rho=−0.7; p<0.001); diastolic BP (rho=−0.108; p=0.03); HDL (rho=0.166; p=0.002); and triglycerides (rho=−0.173; p=0.001). No correlation was seen between change in HbA1c and diabetes duration, baseline BMI, waist circumference, systolic BP, LDL, albuminuria, polypharmacy, and follow-up time at visits or number of visits.

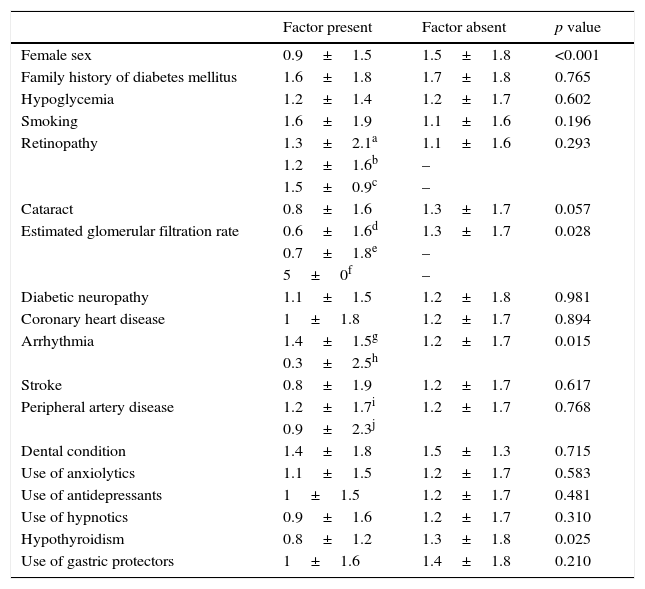

Table 2 shows how HbA1c reduction between the first and last visits varies depending on demographic characteristics and comorbidities. Insulin users had greater HbA1c decreases (−1.4±1.9) than non-insulin users (−0.9±1.3; p<0.001), and patients treated with GLP-1 receptor agonists achieved greater reductions in HbA1c (−1.7±1.8) than those not given these agonists (−1.1±1.6; p=0.015). HbA1c decreased in different groups with hypoglycemic agents in the following proportions (p<0.001): monotherapy, −0.3±0.7; dual therapy, −1.1±1.5; triple therapy, −1.4±1.4; basal insulin, −1.8±1.9; basal-bolus insulin, −1.1±1.8; and insulin mixture, −0.5±0.8. HbA1c decreased −0.09±0.8 when hypoglycemic doses were not adjusted; −0.9±1.4 when their doses were adjusted; and −1.5±1.8 when hypoglycemic agents were changed or added (p<0.001). HbA1c reduction was −1±1.7 when antihypertensive doses were not adjusted; −1.1±1.6 when dose was adjusted; and −1.6±1.6 when antihypertensives were changed or added (p=0.005). Adherent patients showed HbA1c decreases by −1.3±1.6, and non-adherent patients by −0.5±1.8 (p<0.001). Patients who attended all visits achieved HbA1c improvements by −1.3±1.6, while those missing appointments had HbA1c reductions by −0.4±2.2 (p=0.008).

Determinants of HbA1c reduction between the first and last visit.

| Factor present | Factor absent | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 0.9±1.5 | 1.5±1.8 | <0.001 |

| Family history of diabetes mellitus | 1.6±1.8 | 1.7±1.8 | 0.765 |

| Hypoglycemia | 1.2±1.4 | 1.2±1.7 | 0.602 |

| Smoking | 1.6±1.9 | 1.1±1.6 | 0.196 |

| Retinopathy | 1.3±2.1a | 1.1±1.6 | 0.293 |

| 1.2±1.6b | – | ||

| 1.5±0.9c | – | ||

| Cataract | 0.8±1.6 | 1.3±1.7 | 0.057 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate | 0.6±1.6d | 1.3±1.7 | 0.028 |

| 0.7±1.8e | – | ||

| 5±0f | – | ||

| Diabetic neuropathy | 1.1±1.5 | 1.2±1.8 | 0.981 |

| Coronary heart disease | 1±1.8 | 1.2±1.7 | 0.894 |

| Arrhythmia | 1.4±1.5g | 1.2±1.7 | 0.015 |

| 0.3±2.5h | |||

| Stroke | 0.8±1.9 | 1.2±1.7 | 0.617 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 1.2±1.7i | 1.2±1.7 | 0.768 |

| 0.9±2.3j | |||

| Dental condition | 1.4±1.8 | 1.5±1.3 | 0.715 |

| Use of anxiolytics | 1.1±1.5 | 1.2±1.7 | 0.583 |

| Use of antidepressants | 1±1.5 | 1.2±1.7 | 0.481 |

| Use of hypnotics | 0.9±1.6 | 1.2±1.7 | 0.310 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.8±1.2 | 1.3±1.8 | 0.025 |

| Use of gastric protectors | 1±1.6 | 1.4±1.8 | 0.210 |

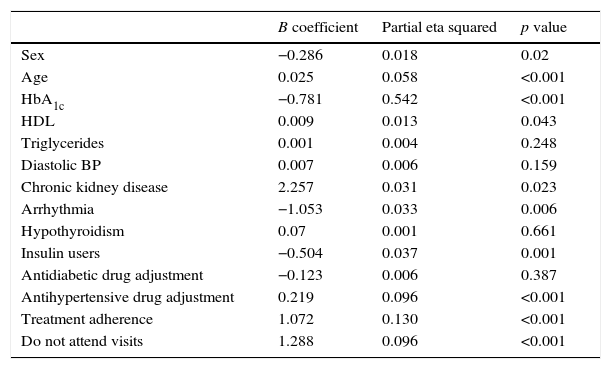

Change in HbA1c between the first and last visits was studied using a linear regression procedure (Table 3). Variables that retained significance in this model to explain the change in HbA1c included sex, age, baseline HbA1c, HDL, chronic kidney disease, arrhythmia, insulin use, adjustment of antihypertensive drugs, treatment adherence, and attendance to the clinic. Baseline HbA1c accounted for 54.2% of the change in HbA1c during follow-up.

Predictors of change in HbA1c in the multivariate analysis.

| B coefficient | Partial eta squared | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | −0.286 | 0.018 | 0.02 |

| Age | 0.025 | 0.058 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c | −0.781 | 0.542 | <0.001 |

| HDL | 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.043 |

| Triglycerides | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.248 |

| Diastolic BP | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.159 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2.257 | 0.031 | 0.023 |

| Arrhythmia | −1.053 | 0.033 | 0.006 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.07 | 0.001 | 0.661 |

| Insulin users | −0.504 | 0.037 | 0.001 |

| Antidiabetic drug adjustment | −0.123 | 0.006 | 0.387 |

| Antihypertensive drug adjustment | 0.219 | 0.096 | <0.001 |

| Treatment adherence | 1.072 | 0.130 | <0.001 |

| Do not attend visits | 1.288 | 0.096 | <0.001 |

R squared=0.682 (adjusted R squared=0.663).

Non-adherence to hypoglycemic agents accounted for 13% of change in HbA1c during follow-up (p<0.001). Non-adherence was detected in 12.5% of patients and was associated to decreased weight reduction (−1.5±5.4kg among adherents; −0.3±6kg among non-adherents, p=0.02) and triglycerides (−38.7±129.8mg/dL among adherent patients; −7.4±104.2mg/dL among non-adherent patients, p=0.009). Non-adherent patients had baseline HbA1c levels of 9.1±2%, while adherent patients had baseline HbA1c levels of 8.5±1.7% (p=0.037). Adherent patients did not differ from non-adherent patients in age, sex, diabetes duration, family history of diabetes, baseline BMI, waist circumference, BP, lipid levels, albuminuria, smoking, and prevalence of comorbidities. Presence of hypoglycemia did not significantly differ in adherence to hypoglycemic agents (91% in patients with hypoglycemia and 86.9% in those with no hypoglycemia; p=0.361).

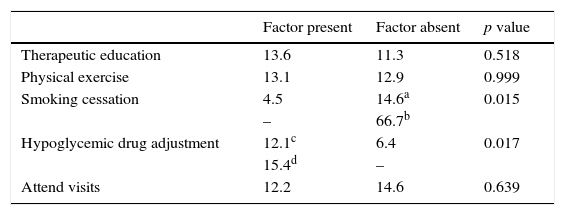

Table 4 shows the lack of adherence to hypoglycemic agents depending on treatments received and follow-up indicators. The number of patients with non-adherence and the proportion they represent in each hypoglycemic agent group were: metformin, 13 (2.9%); sulfonylureas, 6 (9.3%); DPP4 inhibitors, 6 (2.8%); SGLT2 inhibitors, 1 (3.1%); GLP-1 receptor agonists, 7 (8.9%); basal insulin, 17 (5.3%); rapid-acting insulin, 28 (17%), and insulin mixture, 2 (9%); non-adherence was two times more common among insulin users as compared to non-insulin users (16.5% vs 8%; p=0.002). No differences were found between non-adherence seen in patients given GLP-1 receptor agonists and those not receiving GLP-1 receptor agonists (12.8% vs 12.5%; p=0.932). Adherent patients took on average 8.6±4 drugs daily, and non-adherent patients, 8.6±4.1 (p=0.869). Adherent patients required a mean of 2.8±2.2 visits, and non-adherent patients 3.9±3.3 visits (p=0.001). Follow-up time tended to be longer among non-adherent patients (13.9±13.9 months) as compared to adherent patients (10.6±10.7 months; p=0.078).

Percentage of patients with non-adherence to hypoglycemic drugs depending on treatments received and follow-up indicators.

Follow-up visits were not attended by 13.9% of patients. This lack of adherence to visits accounted for 9.6% of change in HbA1c (p<0.001), and as compared to patients who attended visits, was associated to poorer final values of systolic BP (136.6±18.9mmHg vs 131.6±16.5mmHg; p=0.004); diastolic BP (78.8±11.2mmHg versus 75.6±10.2; p=0.018); LDL (103.6±36.1mg/dL vs 93±32.4mg/dL; p=0.015), and triglycerides (178.1±143mg/dL vs 138.4±77.3mg/dL; p=0.003). As compared to patients who attended the visits, those who missed visits were younger (58.9±11.9 years vs 62.5±11.3 years; p=0.007); had worse baseline HbA1c levels (9.5±1.9% vs 8.5±1.7%; p=0.006) and worse albuminuria (157.9±440.2mg/g vs 108.6±540.5mg/g; p=0.008), and were taking fewer drugs per day (7.6±4.1 vs 8.8±4; p=0.004). Non-adherence to visits was significantly greater among smokers (23.5% vs 12.1% of non-smokers; p=0.004); tended to be higher among insulin users (16.5% vs 11% of non-insulin users; p=0.058); was significantly lower among patients with hypothyroidism (2.8% vs 16.1% of non-hypothyroid patients; p=0.001), and tended to be lower among those given therapeutic education (12.4 vs 19% of those not educated; p=0.056). No differences were found between patients who attended and those missing visits in diabetes duration, sex, family history of diabetes, baseline BMI, waist circumference, BP, lipid levels, prevalence of comorbidities other than hypothyroidism, and physical exercise.

Using a multinomial logistic regression procedure, non-insulin use (p=0.011) and smoking cessation (p=0.032) were found to be independent predictors of treatment adherence. When this same statistical procedure was used to define the factors independently predisposing to not attending visits, insulin use (p=0.019) and lack of therapeutic education (p=0.033) were the factors found.

DiscussionIn this study, 66.6% of diabetic patients attending endocrinology outpatient clinics achieved HbA1c values within target, and improvement in HbA1c during follow-up, on average 1.2 points, was mainly determined by baseline HbA1c, treatment adherence, and attendance to appointments.

The greatest HbA1c reduction in patients with higher baseline values had already been reported by Buysschaert et al. in their real-world study with exenatide,12 and by Wilding et al. in their review of clinical trials with canagliflozin.13 Our retrospective study enrolled patients treated with all types of hypoglycemic agents, and it was noted that the higher the baseline HbA1c value, the greater the HbA1c reduction achieved during follow-up. This finding could be related to the strategy of pre-defining HbA1c targets for each patient, as proposed by the American Diabetes Association in their recommendations14 and which involves use of more potent hypoglycemic drugs in patients with higher baseline HbA1c values.

It should be noted that in the model explaining changes in HbA1c during follow-up, the most important factor after baseline HbA1c values was treatment adherence, and that adjustment or change in hypoglycemic agents did not reach statistical significance as an independent predictor of the final HbA1c value. This observation conveys the idea that if the patient does not adhere to the medication prescribed, the importance of adjustments in hypoglycemic drugs that the physician may have considered at previous visits decreases, and hence the interest in a better understanding of the mechanisms that determine treatment adherence. In this regard, Wild reported that for every 25% increase in treatment adherence, a patient's HbA1c decreases by0.34%.15

In our study, non-adherence was found to be two times more common in insulin users as compared to non-insulin users, which may suggest that insulin use represents a critical moment for adherence. Farsaei et al. reported that 28.8% of patients with T2DM given insulin had poor insulin adherence and that some barriers to insulin therapy could be use of multiple drugs, patient concern about interference of insulin therapy with activities of daily living, potential administration site reactions, or associated weight gain.16 In the search for alternatives to the more complex forms of insulin therapy, such as basal-bolus therapy, the 4B and GetGoal DUO-2 studies compared the effect of adding exenatide or lixisenatide, respectively, to insulin glargine, instead of rapid-acting insulin analogues, and found similar HbA1c reductions, with weight improvement and a lower rates of hypoglycemia.17

Unlike insulin users, smokers who were able to quit smoking achieved the best adherence rates to hypoglycemic drugs. A meta-analysis of 14 observational studies including 98,978 diabetic patients found that smoking cessation did not worsen HbA1c in the long term and resulted in an improved lipid profile.18 In the ADVANCE study, which followed 11,140 patients with diabetes, all-cause mortality decreased by 30% after smoking cessation.19 The relationship between smoking cessation and improved treatment adherence seen in our study is an additional stimulus to insist on the smoking cessation counseling recommended for diabetic smokers.

Further studies are needed to clarify the causes leading a diabetic patient not to adhere to hypoglycemic drugs or not to attend visits. The fact that missed medical visits are less frequent among patients receiving therapeutic education reminds us of the essential role of education in management of chronic diseases,20 and invites us to improve the coordination of all professionals involved in diabetic patient care.

ConclusionImprovement in HbA1c values during the follow-up of diabetic patients is determined by baseline HbA1c, treatment adherence, and attendance to appointments. Insulin users have poorer adherence and miss more visits to the clinic, while patients who quit smoking are more adherent to hypoglycemic agents, and those who receive therapeutic education attend the clinic more often.

AuthorshipEGD contributed to study design, followed up patients, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

DRM, FFA, and RVMP followed up patients and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest regarding the content of the study.

Please cite this article as: García Díaz E, Ramírez Medina D, García López A, Morera Porras ÓM. Determinantes de la adherencia a los hipoglucemiantes y a las visitas médicas en pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2017;64:531–538.