To present our experience in the clinical follow-up of patients undergoing a gastric bypass.

MethodDescription of six cases under follow-up by our unit after undergoing a gastric bypass at another private centre.

ResultsThe 6 patients presented complications, the most notable being the death of one patient due to severe malnutrition and the need for revision surgery in another for the same reason, destabilisation of type 1 diabetes mellitus in another patient and fat-soluble vitamin deficiency in all of them.

ConclusionsThere are few publications that support the safety of gastric bypass as a treatment for obesity. In our experience, it is a technique associated with a high rate of serious complications. As it is a technique that is not yet standardised, we consider that these cases should be operated on in centres where there is a multidisciplinary team with expertise in the management of possible complications, with close follow-up by surgeons and endocrinologists.

Presentar nuestra experiencia en el seguimiento clínico de pacientes sometidos a bypass gastroileal.

MétodoDescripción de los 6 casos en seguimiento por nuestra unidad tras haberse sometido a bypass gastroileal en otro centro privado.

ResultadosLos 6 pacientes presentaron complicaciones, destacando el fallecimiento de una paciente por desnutrición severa y la necesidad de reconversión quirúrgica de otra por el mismo motivo, la inestabilización de la diabetes mellitus tipo 1 de otra paciente y el déficit de vitaminas liposolubles en el 100% de los mismos.

ConclusionesSon escasas las publicaciones que avalan la seguridad del bypass gastroileal como tratamiento de la obesidad. En nuestra experiencia es una técnica asociada a alta tasa de complicaciones graves. Al ser una técnica por ahora no estandarizada, consideramos que estos casos debieran intervenirse en centros donde exista un equipo multidisciplinar experto en el manejo de las posibles complicaciones, con un seguimiento estrecho por cirujanos y endocrinólogos.

Bariatric surgery has proven to be the most effective treatment for certain types of obesity, ahead of medical and conservative treatment1,2 and furthermore to improve comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, bone and muscle problems, and sleep apnoea.3,4 The surgical techniques used at present can be classified as malabsorptive, restrictive or mixed. A recent meta-analysis found that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy techniques are superior to laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding and are those most commonly used.5 Today, even though surgery has demonstrated the above-mentioned benefits in patients with obesity, the search continues for new techniques that yield maximum benefits with minimum complications. In this spirit, in 2003 Santoro et al.6 introduced sleeve gastrectomy with transit bipartition, not excluding the duodenum entirely in order to minimise nutritional complications but amplifying early stimulation of the distal small bowel by nutrients. Subsequently, a variant of this technique emerged: the single anastomosis sleeve ileal bypass, whose most recognised author is Mahdy.7 From this variant emerged another modification, and a new technique called gastroileal bypass was created. In Spain, this technique is used in the private sphere by Resa et al.8 To do it, they make a horizontal section of the stomach at the second vessel of the lesser curvature with two or three loads of 60 mm with the Roticulator® endostapler/cutter. To create the alimentary loop and the common channel, which in this technique are the same, as there is a single anastomosis between the stomach and the bowel, at least 250 cm of bowel measured from the ileocaecal valve are used. A laterolateral anastomosis is made from the stomach to the jejunal loop.

This study reports all cases of patients who underwent gastroileal bypass at a private health centre in a different province who subsequently, on their own initiative, requested follow-up in the Department of Endocrinology and Nutrition at Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío [Virgen del Rocío University Hospital] in Seville, their reference hospital.

ResultsCase 1A 67-year-old woman, with a history of hypertension on treatment with valsartan 160 mg/24 h, vitamin A, vitamin D, biotin and calcium, underwent bariatric surgery with a gastroileal bypass and was referred to our practice 13 months later due to malleolar oedema, alopecia and nail abnormalities, after heart disease had been ruled out and no evidence found of proteinuria had been detected. Before the procedure, she weighed 110 kg and was 154 cm tall (body mass index [BMI] 46.38 kg/m2). After the procedure, she lost 40 kg in one year; her weight measured in an appointment was 78 kg (BMI 30.27 kg/m2) with oedema.

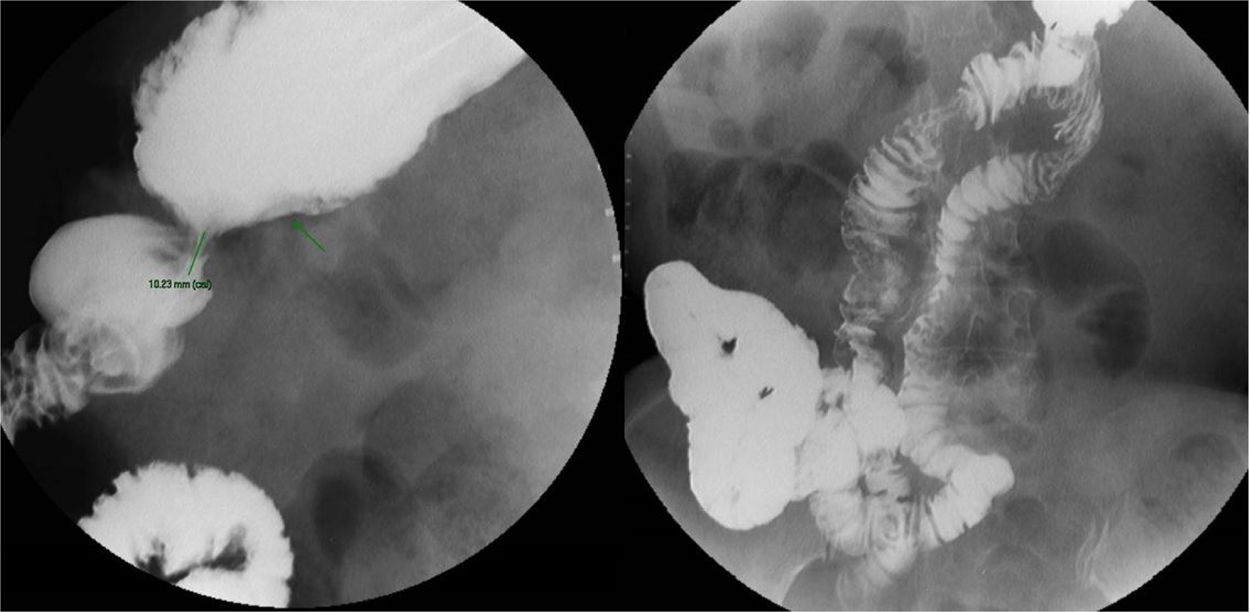

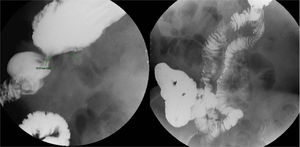

Laboratory testing revealed total protein 5 g/dl, accompanied by hypoalbuminaemia (2.1 g/dl), and a faecal fat test detected steatorrhoea (60 g/day). As regards imaging tests, she underwent a study of the oesophagus, stomach, duodenum and bowel with barium (Fig. 1) that showed changes secondary to the bypass performed, with a gastric reservoir measuring approximately 55 × 88 × 30 mm, stenosis at the anastomosis of 10 mm, slowed bowel transit with a four-hour lapse to reach the colon and a small bowel measuring approximately 119 cm with a very long retrograde loop that filled with contrast.

With clinical judgement of short bowel syndrome and malabsorption in a post-gastroileal bypass patient, stenosis of the gastroileal anastomosis and oedema secondary to hypoproteinaemia due to severe undernutrition, the patient was prescribed oral oligomeric nutritional supplements, modular protein supplements, spironolactone 100 mg/day and Kreon® 25,000 six tablets daily.

After three months, the patient returned with greatly improved oedema and weight loss of 14 kg (weight 55.5 kg), plus improved albumin levels (2.6 g/dl). An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed moderate stenosis of the gastrojejunal anastomosis with a marked periulcer rim and extensive ulceration thereof, featuring a benign appearance. In view of this, a proton pump inhibitor was added to her treatment and she was referred to Surgery to be assessed for treatment of the ulceration at the opening of the anastomosis.

Despite this, after three months, she returned once again, this time with worsened oedema, weight gain of 7.4 kg (weight 62.9 kg) and an increase in bowel movements to four or five per day. Laboratory testing further revealed another drop in albumin (2.3 g/dl) and severe vitamin A and D deficiencies in spite of her replacement therapy. Given the patient’s new clinical situation, her diuretic treatment was changed to furosemide/triamterene, and rifaximin 200 mg every eight hours was added.

After three days, the patient visited the accident and emergency department due to substantially increased oedema, six bowel movements per day and anorexia secondary to her signs and symptoms. Examination found a state of anasarca and severe sarcopenia. Emergency laboratory testing revealed haemoglobin (Hb) 8.8 g/dl, total protein 5.4 g/dl and creatinine 0.48 mg/dl. In addition, an electrocardiogram showed no abnormalities at 80 bpm. The patient was admitted to the Endocrinology and Nutrition ward, and treatment was started with intravenous albumin 10 g/8 h. After this, the patient’s condition improved considerably, though laboratory testing showed Hb 6.9 g/dl with no evidence of bleeding, requiring a transfusion of packed red blood cells. It also showed very low levels of zinc and vitamin A and D, for which she was given oral supplementation of zinc and parenteral supplementation of vitamin A and D. After four days of treatment with diuretics, the patient's weight was 51.8 kg; therefore, after the possibility of surgical reconstruction was assessed, a decision was made to start treatment with parenteral nutrition in order to prevent a state of undernutrition ahead of said reconstruction. Despite this, in a context of intravenous depletion therapy, the patient's weight dropped to 44.8 kg. At that point, she developed polymicrobial catheter-related bacteraemia with Escherichia coli and Klebsiella, treated first with first piperacillin/tazobactam and then antibiogram-directed therapy with intravenous ceftriaxone. Once the patient's infection had resolved, she no longer needed diuretics and remained stable. She was then assessed by General Surgery. After a month of admission, the patient, with a weight of 50 kg and dynamometry of 20 kp (30th to 50th percentile), underwent surgery to convert her gastroileal bypass to a gastric bypass. The operation proceeded without incident and the patient experienced no complications; therefore, she was discharged on the sixth day of the postoperative period.

One month later, the patient was reassessed, revealing a spectacular improvement in her general condition, with no oedema and a weight of 56.5 kg. In addition, her blood protein (6.5 g/dl); albumin (3.7 g/dl); and vitamin A, D and E levels had returned to normal.

Case 2A 60-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism secondary to radioiodine therapy for a toxic multinodular goitre and obesity was referred to our practice for severe undernutrition following gastroileal bypass performed 14 months earlier. Five months after the operation, the patient developed nausea, vomiting of food and a bitter taste between meals that gradually increased, with the addition in the past month of postprandial mesogastric pain, anorexia, asthenia, low-grade fever, weight loss and steatorrhoea. Her usual treatment consisted of furosemide 40 mg/8 h, Kreon® 25,000 5 tablets/24 h, folic acid 5 mg/24 h and levothyroxine 300 μg/day. In an appointment, her weight was recorded as 98.9 kg for a height of 164 cm (BMI 36.77 kg/m2). Before surgery, her usual weight was 160 kg (BMI 59.48 kg/m2). As regards complementary tests, on the one hand, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a remnant gastric chamber from partial gastrectomy with congestive, erythematous mucosa and a surgical anastomosis featuring a large ulceration measuring 1.5 cm, with a central black clot and no adjacent red blood remnants, that might have been degenerated on its enteral aspect. On the other hand, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen (Fig. 2) showed grouping and engorgement of vessels in the left half of the abdomen, pointing to the possibility of a peritoneal adhesion/internal hernia, with no evidence of loop dilation. Multiple gallstones and severe fatty liver disease represented other possibilities. Given this, the patient had her dose of furosemide lowered to 1 tablet/12 h and was prescribed high-protein oral nutritional supplements.

She was re-evaluated after three months, when laboratory testing revealed severe vitamin A and D deficiencies. Supplementation for these deficiencies was then added, as was thiamine.

After a month, the patient was admitted to the Internal Medicine ward in significantly deteriorated general condition, with cellulitis of the left buttock due to Fournier gangrene, acute kidney failure due to low intake and persistent vomiting, anaemia with Hb 7.5 g/dl, and hypoproteinaemia (5.2 g/dl). Despite intensive treatment with antibiotic therapy, serum therapy and even dopamine, the patient suffered from septic shock, due to which she was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit and ultimately died.

Case 3A 26-year-old woman with obesity treated by means of gastroileal bypass visited our practice two years later with repeat episodes of hypoglycaemia. She had no diarrhoea, though she did report that in the first six months after surgery she had experienced steatorrhoea with five or six bowel movements per day. She was on treatment with calcifediol, weighed 64.9 kg and was 167 cm tall (BMI 23.27 kg/m2); prior to surgery, she had weighed 115 kg (BMI 41.23 kg/m2). A diet with raw corn flour and no simple sugars was then recommended; on that diet, the patient reported significant improvement in her episodes of hypoglycaemia. Densitometry revealed osteopenia, for which she was prescribed calcium and vitamin D supplements. Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy showed a small axial hiatal hernia due to sliding, with no evidence of gastro-oesophageal reflux, and a reservoir with mild thickening of folds, featuring a morphologically normal gastrojejunal anastomosis that showed good passage of the contrast medium through the jejunum, and intestinal transit in which the contrast medium passed quickly and without difficulty from the reservoir to the colon, revealing shortened but otherwise morphologically normal small bowel loops and a terminal ileum within normal limits.

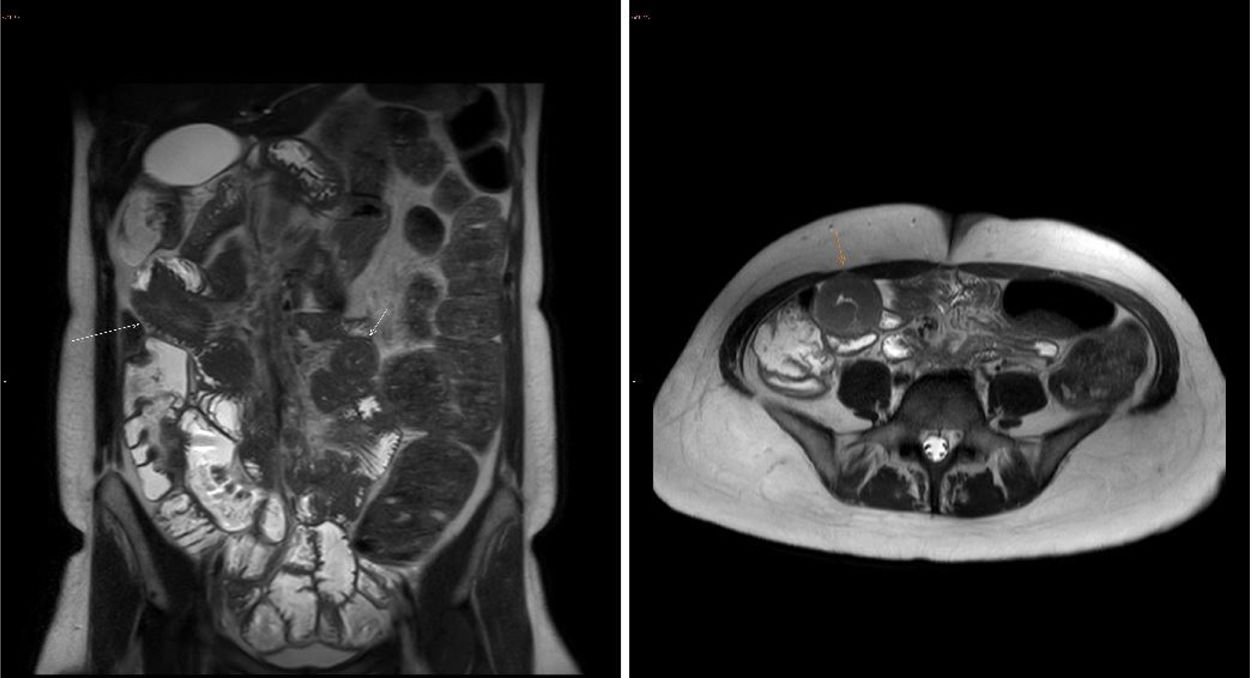

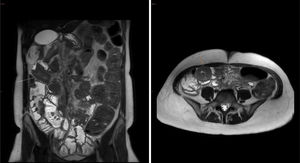

After one year of follow-up, the patient presented iron deficiency anaemia and vitamin A and D deficiencies. She also started to experience abdominal discomfort and frequent vomiting, which she had not previously presented and which led to several visits to the accident and emergency department to request intravenous analgesia. She underwent abdominal ultrasound, as well as CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen, both enhanced with intravenous contrast. CT showed images indicative of small bowel intussusception, apparently of the empty ileum and right iliac fossa, with no clear retrograde obstructive signs; these, given their characteristics, suggested transient intussusception. To them were added slight distension of the colon, in particular the distal transverse colon, splenic flexure and descending colon, filled with faecal matter, with no clear obstructive lesion or wall abnormalities identified. Ultrasound showed abundant meteorism within the colon and slightly distended loops of small bowel with fluid content in the empty left hypochondrium. MRI (Fig. 3) revealed jejunojejunal intussusception in the empty right side and jejunoileal intussusception in the empty right side/iliac fossa and hypogastrium, with no evidence of obstruction and with a redundant sigmoid colon and abundant gas and faecal content in the left half of the colon. All this was consistent with malabsorption. She was then prescribed treatment with rifaximin, but did not improve.

Intravenous contrast-enhanced MRI of the abdomen, performed in Case 3. Jejunojejunal intussusception is seen in the empty right side and jejunoileal intussusception is seen in the empty right iliac fossa and hypogastrium, with no evidence of obstruction and with a redundant sigmoid colon and abundant gas and faecal content in the left half of the colon. All this was consistent with malabsorption.

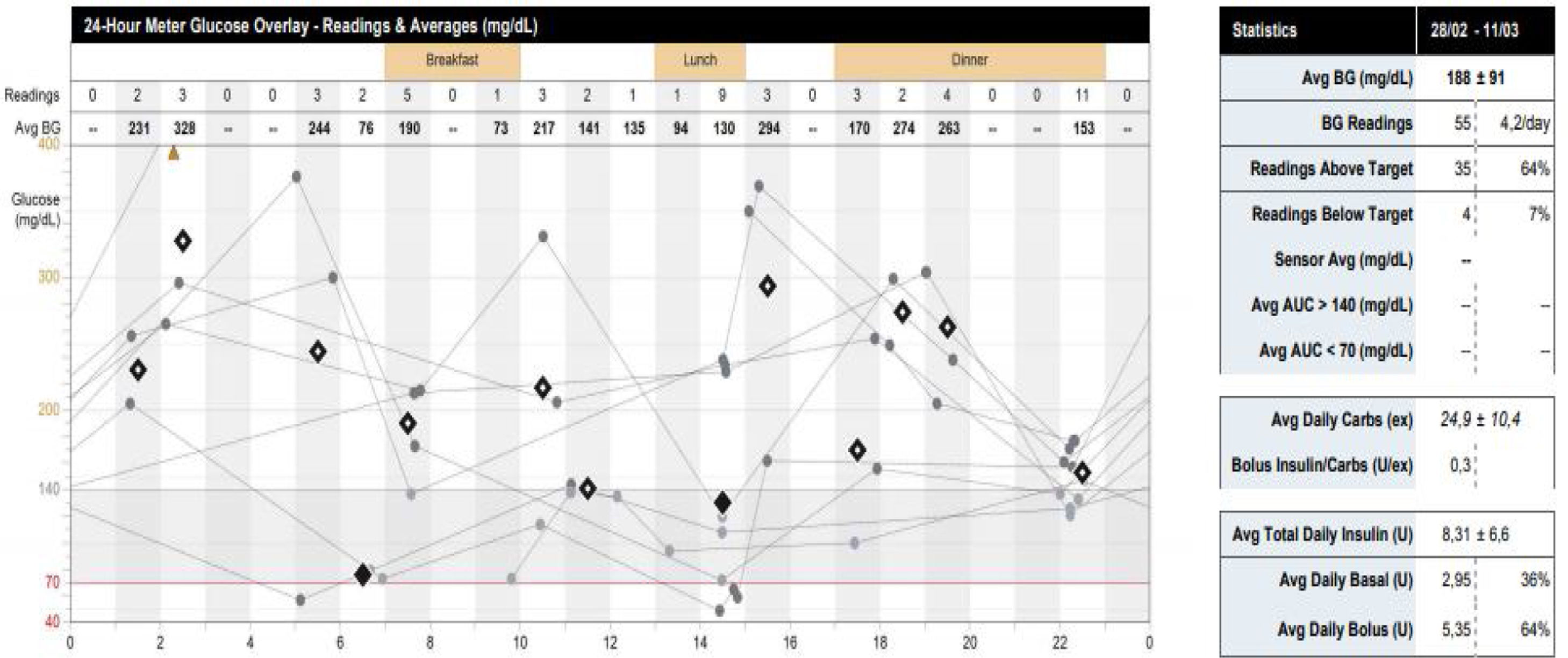

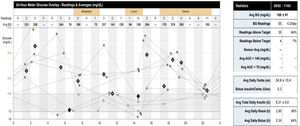

A 48-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, type 1 diabetes with no known complications and morbid obesity treated by means of gastroileal bypass, on treatment with insulin lispro (1.5 IU at each meal) and U300 insulin glargine (4 IU at night), omeprazole, multivitamin complex, calcifediol, and vitamins A and E, came in two years after surgery with severe hypoglycaemia and steatorrhoea with four to five bowel movements per day. On examination, she weighed 64.2 kg and was 161 cm tall (BMI 24.7 kg/m2). Prior to surgery, she had weighed 103 kg (BMI 39.7 kg/m2). Laboratory testing revealed a haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 6.9% and undetectable C-peptide. Given her instability, the patient required treatment with a subcutaneous insulin pump, despite which she continued to experience episodes of hypoglycaemia and substantial instability in blood glucose levels (Fig. 4).

Case 5A 38-year-old man, with a history of bronchial asthma and morbid obesity treated with gastroileal bypass, was on treatment with vitamins A and E, omeprazole, and calcifediol. He visited our practice to start medical follow-up on our Nutrition unit. His weight was 146 kg and his height was 177 cm (BMI 46.6 kg/m2). Prior to surgery, he had weighed 197 kg (62.88 kg/m2). During follow-up, the patient had steatorrhoea with three to four bowel movements per day and an episode of nephrolithiasis due to a calcium oxalate stone.

Case 6A 30-year-old woman, a former smoker, had a history of primary hypothyroidism and obesity treated by means of gastroileal bypass. She was on treatment with L-thyroxine sodium 250 μg/day, retinol/7 days, tocopherol, multivitamin complex, omeprazole and calcifediol. She visited a year after surgery due to a gradually increasing need to raise her levothyroxine dose. Before surgery, she had been taking a dose of 150 μg/day with good treatment compliance. She had no diarrhoea. Examination revealed a weight of 70 kg and a height of 164 cm (BMI 25.71 kg/m2), with a weight prior to surgery of 97 kg (BMI 36 kg/m2). After two years, she returned with dyspepsia. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed no abnormalities, and a transit study with barium revealed right deviation from the midline of both the alimentary loop and the bilioenteric anastomosis, indicative of internal hernia, though with no signs of obstruction. Laboratory testing revealed deficiencies in vitamin A (10 μg/dl [normal range 30–80]) and vitamin E (429.03 μg/dl [normal range 517−1,808]).

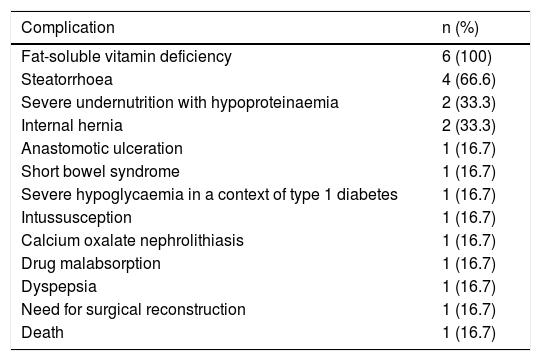

Table 1 shows a summary of the complications presented.

Complications presented by patients having undergone gastroileal bypass in follow-up on our Nutrition unit.

| Complication | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Fat-soluble vitamin deficiency | 6 (100) |

| Steatorrhoea | 4 (66.6) |

| Severe undernutrition with hypoproteinaemia | 2 (33.3) |

| Internal hernia | 2 (33.3) |

| Anastomotic ulceration | 1 (16.7) |

| Short bowel syndrome | 1 (16.7) |

| Severe hypoglycaemia in a context of type 1 diabetes | 1 (16.7) |

| Intussusception | 1 (16.7) |

| Calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis | 1 (16.7) |

| Drug malabsorption | 1 (16.7) |

| Dyspepsia | 1 (16.7) |

| Need for surgical reconstruction | 1 (16.7) |

| Death | 1 (16.7) |

Gastroileal bypass is a novel bariatric surgery modality that should be studied and compared to well-known, standardised techniques to determine whether it is appropriate and whether the risks and side effects are acceptable when weighed against the benefits. A bariatric surgery standardisation document published in 20199 briefly mentioned single-anastomosis gastroileal bypass according to De Luca et al.’s technique,10 in which based on gastric bypass they created a gastroileal anastomosis 300 cm from the ileocaecal valve. This document proposed that this surgery would be indicated in patients who have not lost enough weight, or have regained it, after other bariatric surgeries, and in patients who are to undergo surgery for the first time and are candidates for gastric bypass but have a short bowel. The only study to date on this technique is that published by De Luca et al.10 in 2017, in which single-anastomosis gastroileal bypass was performed on seven patients and those patients were followed up after six months. In that study, one of the patients had hypoalbuminaemia.

Resa et al.,8 for their part, published a 2019 article explaining their surgical technique, gastroileal bypass, and shared the outcomes achieved in 1,512 patients after a two-year follow-up period. The patients included were adults who met the criteria for bariatric surgery of the Spanish National Health System (patients 18–60 years of age with a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 or ≥35 kg/m2 with comorbidities, in some individual cases up to 65 years of age) and underwent surgery between 2010 and 2015. All had comorbidities of obesity before surgery, and their mean BMI was 42.36 ± 6.23 kg/m2. Their results showed a weight loss of 81.51% ± 21.81% after two years and a rate of early complications of 2.71%. As for late complications, 15 (0.99%) had ulcers and stenosis at the anastomosis, eight (0.52%) required endoscopic dilation of the anastomosis, four (0.26%) required surgical dilation of the anastomosis and three (0.19%) developed perforation and required laparoscopic surgery. In their study, no patients required reconversion to Roux-en-Y and two patients required surgical review due to malnutrition.

Our study reported all cases followed up at our hospital after this type of surgery. In their review, Resa et al. noted that their surgery, as it has a longer common channel than in biliopancreatic diversion, results in less steatorrhoea and better absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, and deemed it a “hypoabsorptive” technique. They also reported adjusting bowel length according to patient height and weight, as well as the need for weight loss that this entails. Despite this, in our sample, all patients had fat-soluble vitamin deficiency and required replacement therapy. In addition, four had steatorrhoea and two required high doses of levothyroxine due to the malabsorption that occurred.11

On the other hand, in Resa et al.’s study, two patients required surgical review due to undernutrition. Our study reported two cases of undernutrition due to very severe malabsorption secondary to this surgery. This led to high morbidity for both patients and death for one of them. We believe that the serious nature of these cases calls for reconsideration of the suitability of this surgical technique, or at least the patients in whom it should be indicated. The ages at which these two patients underwent gastroileal bypass — 59 and 66 — is worthy of note. The case of the patient who underwent the procedure at age 66 is of particular interest, since according to the criteria of the Spanish National Health System, the Spanish public health system would never have cleared her for bariatric surgery, especially considering the data on complications and mortality generated with malabsorptive techniques in patients over 65 years of age.12

Another case in which we believe the indication for bariatric surgery was controversial was that of the patient with type 1 diabetes, since it is currently not recommended in patients with this disease. A meta-analysis13 confirmed that bariatric surgery did not significantly improve HbA1c, although it did significantly reduce insulin requirements, despite a weak correlation with BMI. The weight loss achieved, ranging from 8.3 to 16.65 kg/m2, was not correlated with insulin requirements. This suggests that the changes caused by bariatric surgery in patients with type 1 diabetes are due to the changes that occur in certain hormones, such as incretins, which are produced in the digestive tract in response to food. These hormones control blood glucose levels, and their dysregulation in patients who lack pancreatic beta cells, and therefore produce neither insulin nor glucagon to regulate blood glucose, can cause substantial glycaemic instability for patients. This is precisely what happened in our Case 4, resulting in significant worsening of her quality of life with no easy solution.

Finally, in their article, Resa et al. defended the notion that creating a anastomosis decreases the risk of internal hernia. Our study features two patients with an internal hernia, though for the moment neither has presented obstruction thereof.

It is very important when interpreting our results to note that all patients had undergone this surgery at a private centre more than 800 km away from their place of residence. This may limit the detection of complications of a non-standardised surgical technique, especially if the seriousness of some of the complications reported herein are taken into account. It should also be noted that all these patients visited our department on their own initiative to request follow-up due to complications. Therefore, we do not know if there are more patients in our health area who have undergone this type of surgery with or without complications or whether in other health areas in Spain there are other patients with this or another type of complication after undergoing gastroileal bypass.

ConclusionsOur study features patients who requested follow-up on our unit on their own initiative due to complications (some of them very serious) of gastroileal bypass. At present, there is very limited evidence on the efficacy and safety of this surgical technique, and it is important to conduct more studies on the technique itself, as well as the short-term and, in particular, long-term complications that arise in order to assess whether it is a suitable technique and in what type of patients it would be indicated. In addition, as the technique is not yet standardised, we believe that candidates for surgical procedures with techniques that carry a risk of malabsorption should undergo such procedures at centres where there is a multidisciplinary team of experts in the management of possible complications, with close follow-up by surgical staff and endocrinologists.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pereira-Cunill JL, Piñar-Gutiérrez A, Martínez-Ortega AJ, Serrano-Aguayo P, García-Luna PP. Complicaciones a medio plazo en pacientes sometidos a bypass gastroileal. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2022;69:240–246.