Evaluate the results of a healthcare and therapeutic education program (TEP) aimed at young patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) transferred from a pediatric center.

MethodologyThis was a prospective, pre-postest in young T1D patients transferred from 2005–2015. The program has four phases: coordinated transfer, evaluation and objective pacting, knowledge (DKQ2) adherence (SCI-R.es) and quality of life (DQoL and SF12). Results were compared according to Multiple Daily Injections (MDI) vs. Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusión (CSII) and adherence (SCI-R.es <65 vs. >65%).

ResultsA total of 330 patients were transferred (age 18.19±0.82 years, 49% females, glycated hemoglobin [HbA1c] 8.6±1.4%). The program was completed by 68%, and 61% did a group course. While no changes in HbA1c were observed at one year (8.3±1.4 vs. 8.2±1.4%), there were changes in severe hypoglycaemias/patient/year (0.23±0.64 to 0.05±0.34 p<0.001) and mild > 5 hypoglycaemias/patient/week (6.9% vs. 3.9% p=0.09). DQK2 knowledge increased (25.7±3.6 vs. 27.8±3.8 p<0.001), with no changes in quality of life or grade of adherence. Patients with CSII (n=21) performed more blood glucose controls and showed greater program adherence with no changes in metabolic control. Patients with the best initial adherence presented the best control (p<0.0001). A lower initial HbA1c and receiving the group course were associated with better clinical HbA1c results ≥0.5% (p<0.05).

ConclusionsThe TEP improved some parameters of metabolic control without modifying the quality of life in young T1D patients. When comparing patients on MDI vs. CSII, there were no differences in metabolic control but there were when differences were evaluated considering treatment adherence.

Evaluar los resultados de un programa de atención y educación terapéutica (PAET-Traslados) dirigido a jóvenes con diabetes tipo 1 (DT1) trasladados de Pediatría.

MetodologíaEstudio prospectivo, pre-postest en jóvenes con DT1 trasladados entre 2005-2015. El programa tiene cuatro fases: traslado coordinado; valoración y pacto de objetivos; curso en grupo; seguimiento. Al inicio y 12 meses se evaluó control metabólico, conocimientos (DKQ2), adherencia (SCI-R.es) y calidad de vida (DQoL y SF12). Se compararon resultados según tratamiento (Múltiples Dosis de Insulina-MDI vs. Bomba Insulina-BI) y según adherencia (SCI-R.es<65 vs. > 65%).

ResultadosSe trasladaron 330 pacientes (edad 18,19±0,82 años, 49% mujeres, HbA1c 8,6±1,4%). El 68% completó el programa y el 61% realizó el curso en grupo. Al año no se observaron cambios en la HbA1c (8,3±1,4 vs. 8,2±1,4%) aunque si en las hipoglucemias graves/paciente/año (0,23±0,64 a 0,05±0,34 p<0,001) y leves > 5 hipoglucemias/paciente/semana (6,9 vs. 3,9% p=0,09). Aumentaron los conocimientos DQK2 (25,7±3,6 vs. 27,8±3,8 p<0,001), sin cambios en la calidad de vida, ni el grado de adherencia. Los pacientes con BI (n21) realizaron más glucemias capilares y seguimiento del programa, sin observarse cambios de control metabólico. Los pacientes con mejor adherencia inicial presentaron mejor control (p<0,0001). Una menor HbA1c inicial y realizar el curso en grupo se asoció con una mejoría clínica de la HbA1c ≥ 0,5% (p<0,05)

ConclusionesEl PAET-Traslados mejora algunos parámetros del control metabólico sin modificar la calidad de vida. No se observaron diferencias en el control metabólico entre pacientes con MDI vs. BI, aunque si según el grado de adherencia al tratamiento.

Diabetes is a chronic and complex disease that requires medical attention at all stages of life, as well as personal and/or family involvement in order to secure adequate control. Therapeutic education and patient collaboration in self-control are essential elements for preventing acute complications and reducing the risk of long-term problems.1

Follow-up and treatment adherence in chronic diseases such as diabetes represent particularly complex issues during adolescence, a period characterized by physical and psychological changes that make people particularly vulnerable, and which coincides with necessary patient transfer from a pediatric to an adult care setting. In Spain, the Spanish Society of Diabetes (Sociedad Española de Diabetes [SED]) recommends that such transfers should take place between 16–18 years of age.2 Transition is usually defined as the process of moving young adults from pediatric services to adult units. However, it has recently been more pointedly described as a planned process that should address the medical, psychosocial, educational and vocational needs of adolescents who on growing up must learn to live with and adapt to their health condition.3 Between 16–18 years of age, young people demand autonomy and, coinciding with this need, there is a displacement of responsibilities in the self-management of diabetes from the parents to their children. This constitutes a stressful situation on both parts, with the parents also experiencing doubts and uncertainties since they are not yet sure that their offspring can adequately manage the disease.

A recent meta-analysis published by Sheehan et al.4 analyzed 24 studies comparing different transition experiences in 8 different countries (one of them conducted in Spain), and found that in most cases transition appeared to be associated with a decrease in post-transfer clinical care, with a consequent deterioration in disease management. This same review showed that some structured educational programs have a positive impact in terms of an improvement of outcomes. In Spain, according to the consensus document of the Spanish Society of Diabetes,2 the transition of pediatric patients to adult diabetes units is far from optimal, with adverse health effects during both adolescence and adulthood. Since the year 2000, the Diabetes Unit of the Department of Endocrinology and Nutrition of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (Spain) has applied a healthcare and therapeutic education program (TEP) designed and structured for young people transferred from pediatric centers.5

Before 2000, our clinical experience showed us that although 12 months after transfer an educational program targeted at these young people improved their level of knowledge related to diabetes, it did not improve their metabolic control, (unpublished data). The incorporation of young people into the existing educational-care programs in the adult unit was not enough to improve diabetes self-management. The impact of these results led to changes in the educational program, on which the current model is based. Two subsequent evaluations were made in 20045 and 2013.6

In the latest evaluation of the program, we aimed to examine the influence of the healthcare and therapeutic education program (TEP) adapted to the needs of transferred young people with type 1 diabetes (TEP – Transfers), one year after transfer and over a decade (2005–2015), upon metabolic control, self-control skills and quality of life. Likewise, we aimed to determine whether multiple daily injection (MDI) therapy vs. insulin pump (IP) and the degree of adherence to self-management of treatment influenced the different variables analyzed at the start and end of the program, with a view to defining different patient profiles.

Patients and methodsA one-year prospective, longitudinal pre/post-test study was carried out on people with T1D transferred at 18 years of age from pediatric centers – mainly from Hospital Sant Joan de Déu (Esplugas de Llobregat) – to the adult center at Hospital Clínic de Barcelona during the decade 2005–2015. All young people with T1D were included in the study. Young individuals with type 2 diabetes and/or with severe mental impairment with no possibility of performing safe care related to diabetes were excluded.

Two years before transfer, the pediatric center prepares the process prior to discharge, promoting the autonomy of young people in diabetes management. At 18 years of age, the patients are transferred to the adult hospital with a clinical and educational report, and a previously scheduled visit to the new center takes place. The patients are given an information leaflet welcoming them to the new center and explaining the logistics of the place, describing all the activities to be performed during this first year, along with contact and emergency care telephone numbers, and photos of the pediatric and adult care professionals. They are then incorporated into a healthcare and therapeutic education program (TEP – Transfers)6 specifically designed for this group of subjects. The supervisors of both teams coordinate the transition structure and process, meeting on an annual basis. The adult unit is responsible for arranging joint visits to the endocrinologist and the nurse responsible for patient education.

The TEP lasts 12 months. It comprises four structured phases: (1) First clinical-educational visit; (2) Homogeneous group course; (3) Individual follow-up with quarterly visits and telematics or complementary visits, according to the needs of the young individual; (4) Evaluation and discharge from the program. Up until 2007, all patients were treated with MDI, though from that date onwards, some of them were transferred under IP treatment that continued at the adult center. Starting in 2009, a new variable was added to the assessment of TEP-Transfers: adherence to self-management of treatment.

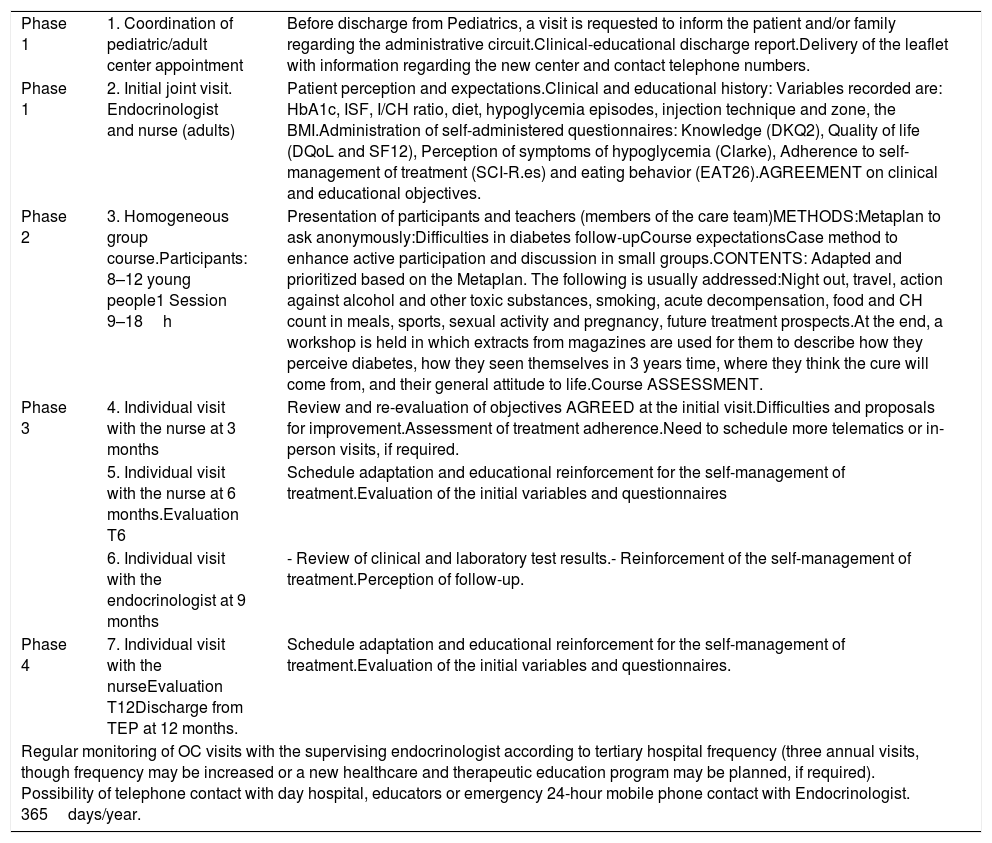

Table 1 describes the care process, taking into account coordination prior to transfer, the periodicity of the visits, the professionals in charge at each visit, and the activities performed during the first 12 months. After this period, the young person continues the standard visits of a tertiary hospital. The time spent per patient during TEP-Transfers ranges from 12–15h, with half of this time being on a group basis.

Care process during the first year of patients with T1D in their transition from Pediatrics to the adult center (TEP-Transfers).

| Phase 1 | 1. Coordination of pediatric/adult center appointment | Before discharge from Pediatrics, a visit is requested to inform the patient and/or family regarding the administrative circuit.Clinical-educational discharge report.Delivery of the leaflet with information regarding the new center and contact telephone numbers. |

| Phase 1 | 2. Initial joint visit. Endocrinologist and nurse (adults) | Patient perception and expectations.Clinical and educational history: Variables recorded are: HbA1c, ISF, I/CH ratio, diet, hypoglycemia episodes, injection technique and zone, the BMI.Administration of self-administered questionnaires: Knowledge (DKQ2), Quality of life (DQoL and SF12), Perception of symptoms of hypoglycemia (Clarke), Adherence to self-management of treatment (SCI-R.es) and eating behavior (EAT26).AGREEMENT on clinical and educational objectives. |

| Phase 2 | 3. Homogeneous group course.Participants: 8–12 young people1 Session 9–18h | Presentation of participants and teachers (members of the care team)METHODS:Metaplan to ask anonymously:Difficulties in diabetes follow-upCourse expectationsCase method to enhance active participation and discussion in small groups.CONTENTS: Adapted and prioritized based on the Metaplan. The following is usually addressed:Night out, travel, action against alcohol and other toxic substances, smoking, acute decompensation, food and CH count in meals, sports, sexual activity and pregnancy, future treatment prospects.At the end, a workshop is held in which extracts from magazines are used for them to describe how they perceive diabetes, how they seen themselves in 3 years time, where they think the cure will come from, and their general attitude to life.Course ASSESSMENT. |

| Phase 3 | 4. Individual visit with the nurse at 3 months | Review and re-evaluation of objectives AGREED at the initial visit.Difficulties and proposals for improvement.Assessment of treatment adherence.Need to schedule more telematics or in-person visits, if required. |

| 5. Individual visit with the nurse at 6 months.Evaluation T6 | Schedule adaptation and educational reinforcement for the self-management of treatment.Evaluation of the initial variables and questionnaires | |

| 6. Individual visit with the endocrinologist at 9 months | - Review of clinical and laboratory test results.- Reinforcement of the self-management of treatment.Perception of follow-up. | |

| Phase 4 | 7. Individual visit with the nurseEvaluation T12Discharge from TEP at 12 months. | Schedule adaptation and educational reinforcement for the self-management of treatment.Evaluation of the initial variables and questionnaires. |

| Regular monitoring of OC visits with the supervising endocrinologist according to tertiary hospital frequency (three annual visits, though frequency may be increased or a new healthcare and therapeutic education program may be planned, if required). Possibility of telephone contact with day hospital, educators or emergency 24-hour mobile phone contact with Endocrinologist. 365days/year. | ||

OC: outpatient clinic; Clarke: hypoglycemia symptom perception questionnaire; DKQ2: Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire 2; DQoL: T1D-specific quality of life questionnaire; EAT26: eating attitudes test; SF12: general health-related quality of life questionnaire; HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin; BMI: body mass index; I/CH: insulin/carbohydrate ratio; SCI-R.es: self-management of treatment adherence questionnaire; ISF: insulin sensitivity factor.

The following variables are recorded at baseline and at 6 and 12 months:

- 1.

Age (years), gender, years from onset of T1D.

- 2.

Type of treatment: multiple daily injections (MDI – number of injections/day) or IP. Units of insulin/24h, units in the form of insulin bolus and units as basal insulin.

- 3.

Metabolic control: glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c %). Frequency of mild hypoglycemia (capillary blood glucose <70mg/dl) episodes per week (<3/week; >5/week). Frequency of severe hypoglycemia episodes (the help of another person being required to resolve the episode) in the previous year.

- 4.

Weight (kg), height (m), the body mass index (BMI) kg/m2.

- 5.

The presence and severity of lipodystrophy at the insulin injection sites: mild (palpable) or severe (palpable and visible).

- 6.

Number of capillary blood glucose (CG) measurements/week.

- 7.

Diabetes knowledge: Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire 2 (DKQ2), with 16 multiple-choice questions. Maximum score: 35.7

- 8.

Perception of quality of life:

- a.

Diabetes Quality of Life (DQoL). This questionnaire has four scales: Impact (17–85), Satisfaction (15–75), Social and occupational concern (7–35), and Diabetes concern (4–20).8 The minimum and maximum scores of the scales appear in parentheses. Lower scores indicate improved perception.

- b.

SF-12 Test. This explores quality of life in general.9 It comprises 12 questions (12–47), with higher scores indicating improved perception.

- a.

- 9.

Perception of the symptoms of hypoglycemia. The Clarke test. This test consists of 8 questions that can be classified as R (reduced perception) or A. Scores of over 3 indicate altered perception of symptoms and signs of hypoglycemia.10,11

- 10.

Eating behavior. EAT26 eating attitudes test. This consists of 26 questions. A score of over 20 is considered abnormal and indicates the need to specifically assess this problem.12

- 11.

Treatment adherence. SCI-R.es self-care inventory-revised.es. This consists of 15 questions related to different aspects of treatment adherence. The score ranges from 0–100. A score of ≥65 represents high adherence (HA), while <65 represents low adherence (LA).13,14

Based on the results obtained for all these variables, the improvement objectives are assessed, and objectives and strategies are agreed upon, based on individual needs.

The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were reported as absolute frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were reported as the mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR). For the comparison of results between the initial visit and after 12 months, the Student t-test for paired samples was used for quantitative variables, while the chi-square test was used for qualitative variables. For the comparison of patients treated with MDI and IP, and for the comparison of patients with high and low adherence, use was made of the Student t-test for independent samples in the case of quantitative variables, and the chi-square test in the case of qualitative variables.

A univariate logistic regression model was used for all the variables analyzed. For variables with p<0.05, we generated a multivariate logistic regression model to search for the combination of variables that best explained the optimization of metabolic control (HbA1c decrease >0.5%). An α error of 0.05 was assumed for all statistical tests. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), version 23, was used throughout.

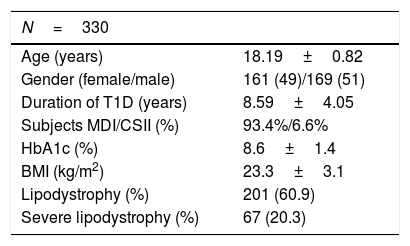

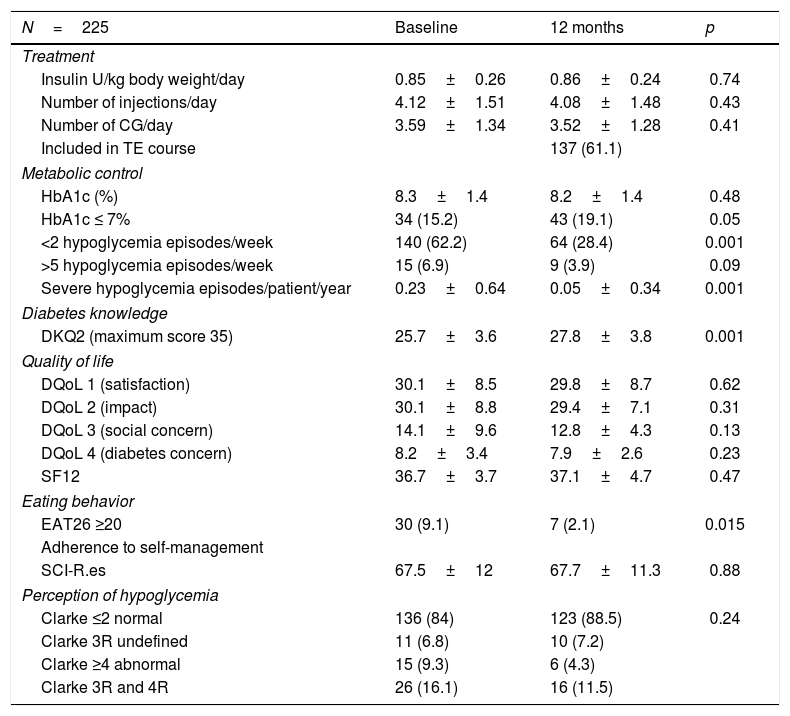

ResultsOutcomes of TEP-transfers, decade 2005–2015In the period 2005–2015, a total of 330 patients were transferred, with a mean age of 18.2±0.7 years; of these, 161 were females (49%), and the mean HbA1c concentration was 8.6±1.4% (Table 2). Of the total patients, 225 completed the program (68%). With regard to metabolic control, no statistically significant changes were seen between the initial HbA1c value and that recorded at 12 months (8.3±1.4 vs. 8.2±1.4%). However, the number of severe hypoglycemia episodes/patient/year decreased from 0.31±0.95 to 0.05±0.34 (p<0.001), and the percentage of patients with >5 mild hypoglycemia episodes/week was reduced by almost half, though statistical significance was not reached (from 6.9% to 3.9%; p=0.09). The percentage of patients with altered perception of hypoglycemia (Clarke test ≥3) was reduced from 16.1% to 11.5%, though here again statistical significance was not reached (p=0.24). Sixty-one percent of the patients attended the course on a group basis. Knowledge of diabetes (DKQ2) increased from 25.7±3.6 to 27.8±3.8 (p<0.001). There was no impairment in quality of life (DQoL and SF12), and no significant changes in adherence to the self-management of treatment (SCI-R.es), though the percentage of patients with altered eating behavior (EAT26) improved (p<0.015) (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, on examining the years from onset of the disease, HbA1c, gender, course attendance and the knowledge test score, we found lower baseline HbA1c (p<0.001) and group course attendance (p<0.036) to be the only variables related to a clinically significant improvement of HbA1c (difference ≥0.5%).

Characteristics of young people with T1D transferred from pediatric centers to the adult center between 2005–2015.

| N=330 | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18.19±0.82 |

| Gender (female/male) | 161 (49)/169 (51) |

| Duration of T1D (years) | 8.59±4.05 |

| Subjects MDI/CSII (%) | 93.4%/6.6% |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.6±1.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.3±3.1 |

| Lipodystrophy (%) | 201 (60.9) |

| Severe lipodystrophy (%) | 67 (20.3) |

Data expressed as number (percentage) or mean±standard deviation.

T1D: type 1 diabetes; HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin; BMI: body mass index; CSII: continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion device; MDI: multiple daily injections.

Comparison of the characteristics at the start and at 12 months of the young transferred patients included in TEP-Transfers.

| N=225 | Baseline | 12 months | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | |||

| Insulin U/kg body weight/day | 0.85±0.26 | 0.86±0.24 | 0.74 |

| Number of injections/day | 4.12±1.51 | 4.08±1.48 | 0.43 |

| Number of CG/day | 3.59±1.34 | 3.52±1.28 | 0.41 |

| Included in TE course | 137 (61.1) | ||

| Metabolic control | |||

| HbA1c (%) | 8.3±1.4 | 8.2±1.4 | 0.48 |

| HbA1c ≤ 7% | 34 (15.2) | 43 (19.1) | 0.05 |

| <2 hypoglycemia episodes/week | 140 (62.2) | 64 (28.4) | 0.001 |

| >5 hypoglycemia episodes/week | 15 (6.9) | 9 (3.9) | 0.09 |

| Severe hypoglycemia episodes/patient/year | 0.23±0.64 | 0.05±0.34 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes knowledge | |||

| DKQ2 (maximum score 35) | 25.7±3.6 | 27.8±3.8 | 0.001 |

| Quality of life | |||

| DQoL 1 (satisfaction) | 30.1±8.5 | 29.8±8.7 | 0.62 |

| DQoL 2 (impact) | 30.1±8.8 | 29.4±7.1 | 0.31 |

| DQoL 3 (social concern) | 14.1±9.6 | 12.8±4.3 | 0.13 |

| DQoL 4 (diabetes concern) | 8.2±3.4 | 7.9±2.6 | 0.23 |

| SF12 | 36.7±3.7 | 37.1±4.7 | 0.47 |

| Eating behavior | |||

| EAT26 ≥20 | 30 (9.1) | 7 (2.1) | 0.015 |

| Adherence to self-management | |||

| SCI-R.es | 67.5±12 | 67.7±11.3 | 0.88 |

| Perception of hypoglycemia | |||

| Clarke ≤2 normal | 136 (84) | 123 (88.5) | 0.24 |

| Clarke 3R undefined | 11 (6.8) | 10 (7.2) | |

| Clarke ≥4 abnormal | 15 (9.3) | 6 (4.3) | |

| Clarke 3R and 4R | 26 (16.1) | 16 (11.5) | |

Data expressed as number (percentage) or mean±standard deviation.

Clarke: hypoglycemia symptom perception questionnaire; DKQ2: Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire 2; DQoL: T1D-specific quality of life questionnaire; EAT26: eating attitudes test; TE: therapeutic education; CG: capillary blood glucose; HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin; SCI-R.es: self-management of treatment adherence questionnaire; SF12: general health-related quality of life questionnaire.

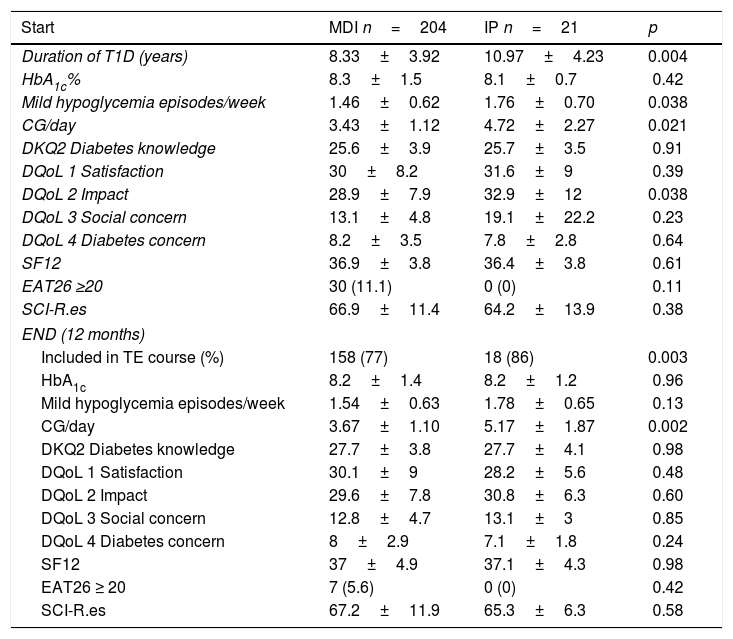

The transfer of patients treated with IP started in 2007. Comparisons were made of the characteristics of the young patients with IP vs. those with MDI. At the time of transfer, the patients with IP (n=21) vs. those treated with MDI (n=204) had a longer duration of T1D (10.97±4.23 vs. 8.33±3.92; p=0.004), an increased frequency of mild hypoglycemia episodes/week (1.76±0.70 vs. 1.46±0.62; p=0.038), and a greater number of CG measurements/day (4.72±2.27 vs. 3.43±1.12; p=0.021). It should be noted that the patients with IP showed poorer perception on the impact scale of the quality of life questionnaire (p=0.038). At 12 months, the percentage of patients completing the course on a group basis was higher in those treated with IP (86 vs. 77%; p=0.003). Likewise, the patients with IP were seen to continue to perform more daily CG measurements after 12 months (5.17±1.87 vs. 3.67±1.10; p<0.002). No significant differences were observed in relation to the other variables analyzed (Table 4).

Comparative results of patients according to type of treatment MDI vs. IP at start and end of TEP-Transfers.

| Start | MDI n=204 | IP n=21 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of T1D (years) | 8.33±3.92 | 10.97±4.23 | 0.004 |

| HbA1c% | 8.3±1.5 | 8.1±0.7 | 0.42 |

| Mild hypoglycemia episodes/week | 1.46±0.62 | 1.76±0.70 | 0.038 |

| CG/day | 3.43±1.12 | 4.72±2.27 | 0.021 |

| DKQ2 Diabetes knowledge | 25.6±3.9 | 25.7±3.5 | 0.91 |

| DQoL 1 Satisfaction | 30±8.2 | 31.6±9 | 0.39 |

| DQoL 2 Impact | 28.9±7.9 | 32.9±12 | 0.038 |

| DQoL 3 Social concern | 13.1±4.8 | 19.1±22.2 | 0.23 |

| DQoL 4 Diabetes concern | 8.2±3.5 | 7.8±2.8 | 0.64 |

| SF12 | 36.9±3.8 | 36.4±3.8 | 0.61 |

| EAT26 ≥20 | 30 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 0.11 |

| SCI-R.es | 66.9±11.4 | 64.2±13.9 | 0.38 |

| END (12 months) | |||

| Included in TE course (%) | 158 (77) | 18 (86) | 0.003 |

| HbA1c | 8.2±1.4 | 8.2±1.2 | 0.96 |

| Mild hypoglycemia episodes/week | 1.54±0.63 | 1.78±0.65 | 0.13 |

| CG/day | 3.67±1.10 | 5.17±1.87 | 0.002 |

| DKQ2 Diabetes knowledge | 27.7±3.8 | 27.7±4.1 | 0.98 |

| DQoL 1 Satisfaction | 30.1±9 | 28.2±5.6 | 0.48 |

| DQoL 2 Impact | 29.6±7.8 | 30.8±6.3 | 0.60 |

| DQoL 3 Social concern | 12.8±4.7 | 13.1±3 | 0.85 |

| DQoL 4 Diabetes concern | 8±2.9 | 7.1±1.8 | 0.24 |

| SF12 | 37±4.9 | 37.1±4.3 | 0.98 |

| EAT26 ≥ 20 | 7 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 0.42 |

| SCI-R.es | 67.2±11.9 | 65.3±6.3 | 0.58 |

Data expressed as number (percentage) or mean±standard deviation.

IP: insulin pump; DKQ2: Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire 2; DQoL: T1D-specific quality of life questionnaire; EAT26: eating attitudes test; TE: therapeutic education; HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin; MDI: multiple daily injections; SCI-R.es: self-management of treatment adherence questionnaire; SF12: general health-related quality of life questionnaire.

From 2009 onwards, a new variable was added to TEP - Transfers: adherence to the self-management of treatment. Between 2009 and 2015, a total of 215 patients with T1D were consecutively transferred from the pediatric to the adult hospital (mean age 18.2±0.5 years; 51.2% males, HbA1c 8.6±1.6%). Of these subjects, 182 completed the SCI-R.es questionnaire.13,14 The latter assesses patient perception regarding their degree of adherence to self-care behavior in diabetes, as recommended by the healthcare professional over the previous 1–2 months. Self-care is defined as the tasks related to diabetes management which the patient should perform daily. The questionnaire consists of 15 questions: four related to diet, two to the self-monitoring of glucose, three to insulin administration, one to physical exercise, two to hypoglycemia, and three to preventive aspects of self-care. The answers are graded using a Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The result is expressed as the weighted mean of the scores on a 0–100 scale.

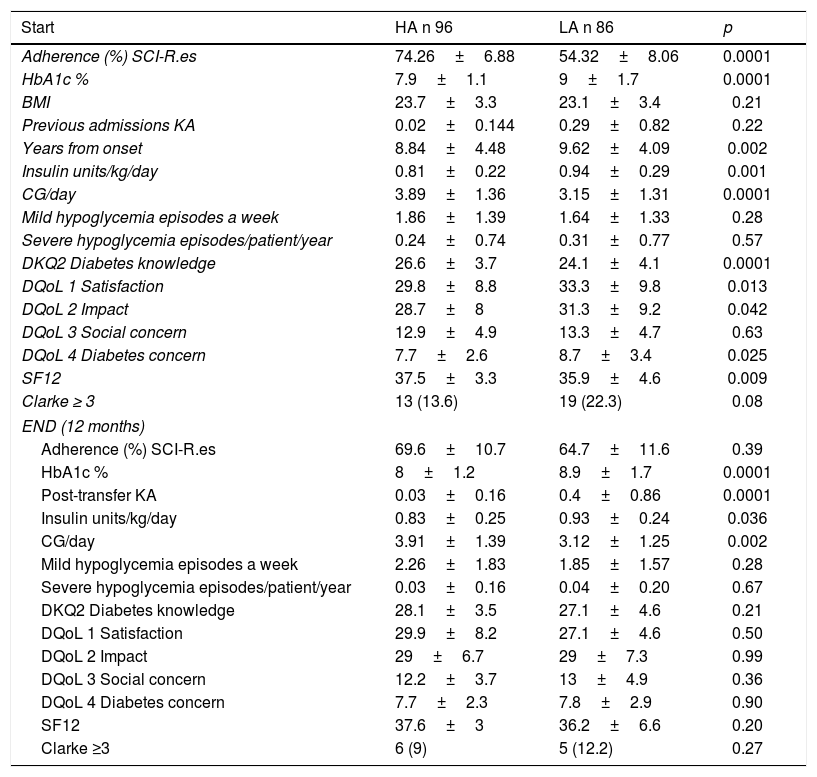

The patients with high adherence (HA SCI-R.es score ≥65) vs. those with low adherence (LA SCI-R score <65) showed a shorter duration of T1D (8.84±4.48 vs. 9.62±4.09 years; p=0.002), used a lower insulin dose per day (0.81±0.22 vs. 0.94±0.29u/kg/day; p=0.001), performed a greater number of CG measurements per day (3.89±1.36 vs. 3.15±1.31; p=0.0001), presented lower HbA1c (7.9±1.1 vs. 9±1.7%; p=0.0001), and performed more favorably on all scales of the DQoL8 except the social and occupational concern scale (Table 5). There were no significant differences in the BMI, the number of mild hypoglycemia episodes/week, the number of severe hypoglycemia episodes/year, or the number of admissions due to ketoacidosis (KA).

Comparative results of the patients according to the degree of self-management of treatment at the start and end of TEP.

| Start | HA n 96 | LA n 86 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence (%) SCI-R.es | 74.26±6.88 | 54.32±8.06 | 0.0001 |

| HbA1c % | 7.9±1.1 | 9±1.7 | 0.0001 |

| BMI | 23.7±3.3 | 23.1±3.4 | 0.21 |

| Previous admissions KA | 0.02±0.144 | 0.29±0.82 | 0.22 |

| Years from onset | 8.84±4.48 | 9.62±4.09 | 0.002 |

| Insulin units/kg/day | 0.81±0.22 | 0.94±0.29 | 0.001 |

| CG/day | 3.89±1.36 | 3.15±1.31 | 0.0001 |

| Mild hypoglycemia episodes a week | 1.86±1.39 | 1.64±1.33 | 0.28 |

| Severe hypoglycemia episodes/patient/year | 0.24±0.74 | 0.31±0.77 | 0.57 |

| DKQ2 Diabetes knowledge | 26.6±3.7 | 24.1±4.1 | 0.0001 |

| DQoL 1 Satisfaction | 29.8±8.8 | 33.3±9.8 | 0.013 |

| DQoL 2 Impact | 28.7±8 | 31.3±9.2 | 0.042 |

| DQoL 3 Social concern | 12.9±4.9 | 13.3±4.7 | 0.63 |

| DQoL 4 Diabetes concern | 7.7±2.6 | 8.7±3.4 | 0.025 |

| SF12 | 37.5±3.3 | 35.9±4.6 | 0.009 |

| Clarke ≥ 3 | 13 (13.6) | 19 (22.3) | 0.08 |

| END (12 months) | |||

| Adherence (%) SCI-R.es | 69.6±10.7 | 64.7±11.6 | 0.39 |

| HbA1c % | 8±1.2 | 8.9±1.7 | 0.0001 |

| Post-transfer KA | 0.03±0.16 | 0.4±0.86 | 0.0001 |

| Insulin units/kg/day | 0.83±0.25 | 0.93±0.24 | 0.036 |

| CG/day | 3.91±1.39 | 3.12±1.25 | 0.002 |

| Mild hypoglycemia episodes a week | 2.26±1.83 | 1.85±1.57 | 0.28 |

| Severe hypoglycemia episodes/patient/year | 0.03±0.16 | 0.04±0.20 | 0.67 |

| DKQ2 Diabetes knowledge | 28.1±3.5 | 27.1±4.6 | 0.21 |

| DQoL 1 Satisfaction | 29.9±8.2 | 27.1±4.6 | 0.50 |

| DQoL 2 Impact | 29±6.7 | 29±7.3 | 0.99 |

| DQoL 3 Social concern | 12.2±3.7 | 13±4.9 | 0.36 |

| DQoL 4 Diabetes concern | 7.7±2.3 | 7.8±2.9 | 0.90 |

| SF12 | 37.6±3 | 36.2±6.6 | 0.20 |

| Clarke ≥3 | 6 (9) | 5 (12.2) | 0.27 |

Data expressed as number (percentage) or mean±standard deviation.

High adherence (HA) SCI-R score ≥65%.

Low adherence (LA) SCI-R score <65%.

KA: ketoacidosis; Clarke: hypoglycemia symptom perception questionnaire; DKQ2: Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire 2; DQoL: T1D-specific quality of life questionnaire; CG: capillary blood glucose; HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin; BMI: body mass index; SCI-R.es: self-management of treatment adherence questionnaire; SF12: general health-related quality of life questionnaire.

The difference in mean score of the adherence questionnaire between the HA and LA disappeared after 12 months of follow-up. At that time there were still significant differences between the two groups in some of the variables for which differences were observed at the time of transfer. In addition, at the end of follow-up, the number of KA episodes/patient/year was lower in the HA group (0.03±0.16 vs. 0.4±0.86; p=0.0001). No statistically significant differences were observed in terms of the other variables analyzed (Table 5). Glycosylated hemoglobin was significantly correlated to the degree of adherence at both baseline (r=−0.422; p<0.001) and at the end of follow-up (r=−0.364; p<0.001).

DiscussionFollowing the recommendations of scientific bodies, the centers involved in this study continue to implement the transition program targeted at young patients with T1D transferred from Pediatrics to an adult center. Since the publication of its first results in 2004, this program has regularly been adapted to changing needs, with the introduction of new variables. In the present latest evaluation, our TEP shows that two-thirds of all patients who completed the entire program experienced improvements in some educational competences, without any worsening of the perception of quality of life. In addition, one of the complications most feared by patients and professionals alike – severe hypoglycemia – was significantly reduced, with no worsening of the degree of metabolic control in terms of HbA1c concentration. A decrease was also observed in the number of patients with <2 mild hypoglycemia episodes/week at the end of the program, with no increase in the number of individuals with >5episodes/week. Another positive outcome has been improved knowledge and a decrease in patients with abnormal eating behavior at the end of the TEP. Transfer coordination has proved effective, since 100% of the patients reported to the first visit in the adult hospital, even though one-third of them did not complete the TEP. From our point of view, these results are particularly relevant considering the characteristics of the study population.

This new evaluation of the TEP has allowed us to analyze the profile of patients treated with IP vs. MDI. At the start of the TEP, the patients with IP presented more years since T1D onset, a higher frequency of mild hypoglycemia episodes, and performed more CG controls, though they yielded poorer scores on the impact scale of the DQoL questionnaire. At the end of the TEP, the patients with IP continued to perform more CG controls and a greater percentage attended the therapeutic education course on a group basis, with no differences in terms of the other variables analyzed.

Likewise, we compared the patients at the start and end of the TEP according to the degree of adherence, thereby making it possible to establish the profile of patients with HA. The latter patients presented fewer years of diabetes, better metabolic control, fewer insulin requirements/day, more CG measurements, a higher level of knowledge, and better perception of quality of life. At the end of the TEP, the patients with HA continued to have better metabolic control, fewer KA episodes during the year after transfer, and also more CG controls. Glycosylated hemoglobin was negatively correlated to the degree of adherence at both baseline and the end of the TEP.

On comparing our results with those reported by other authors in relation to metabolic control, great variability is observed in the many published studies, as commented by Lyons et al. in their review.15 Thus, while some articles report improved patient HbA1c levels,16–20 others describe poorer levels.21,22 These data reflect the difficulties in establishing consensus on the approach to this patient population. A lack of attendance at follow-up visits has been reported in other publications.18 This aspect improves in those patients who have become familiarized with the professional team before transfer takes place, as described by Kipps et al.23 In our case, all the patients attended the first visit in the adult hospital, though one-third did not complete the TEP. The distance between the pediatric and adult hospitals may explain this situation, which we attempt to resolve through annual coordination of the teams and the distribution of information leaflets in which photos of the professionals involved are provided.

Although the transfer process is experienced as a challenge by most professional teams, few randomized studies on the different transition modes have been carried out. Of note in this regard is the study conducted in Canada by Spaic et al.,24 with the inclusion of a transfer coordinator in the intervention group that resulted in improved satisfaction and adherence to the follow-up visits, though it had no impact in terms of the improvement of metabolic control. The HbA1c values in the intervention group were 8.5±1.3% vs. 8.6±1.6% in the control group, with values of 8.6±1.5 and 8.6±1.5%, respectively, at 18 months. Our single study cohort and the adoption of a pre-post intervention observational design referring to the TEP yielded similar results in terms of HbA1c (8.3±1.4% at baseline and 8.2±1.4% at 12 months). In addition, we observed a decrease at the end of the TEP in the frequency of mild and severe hypoglycemia episodes, these being variables not analyzed in the study published by Spaic et al.24

We compared the outcomes of the TEP according to the type of treatment, i.e., IP vs. MDI. Some authors reported improvements with IP vs. MDI in children and young subjects,25,26 while other investigators emphasized greater satisfaction among patients treated with IP vs. MDI, though these results had no impact in terms of improved metabolic control.27 In our setting, the clinical differences and the results in terms of metabolic control and T1D management between the two groups at baseline were probably due to the fact that treatment with IP was initially started in patients with poorer diabetes control or with recurrent hypoglycemia, with this accounting for the poorer score on the impact scale of the DQoL, as reported by other authors.28 At the end of TEP-Transfers, the results of the program were seen to be comparable, although some differences relating to self-control, such as the number of daily CG measurements, persisted. Significantly, the patients treated with IP attended the group sessions in comparatively greater numbers.

An important novel aspect of our study was the evaluation of the outcomes according to the degree of adherence. Improved treatment adherence was associated with better clinical outcomes, better HbA1c levels, fewer admissions due to KA, and a lower number of severe hypoglycemia episodes. In addition, in patients with poorer self-management of T1D, TEP-Transfers improved the results of the adherence questionnaire by 10 points. There are not many studies which relate adherence to T1D treatment with clinical outcomes. In our study we used a validated questionnaire for this purpose, specifically the SCI-R.es,14 an instrument previously used to assess whether parental family support favored adherence on the part of young people to self-management of the disease.29 Specific strategies to assess and promote adherence to T1D treatment in this population should form part of any transition program.

With regard to the negative correlation observed between HbA1c and the degree of adherence to self-care, our results both at the start of TEP (r=−0.422) and at the end (r=−0.364) are consistent with those reported in the literature. Weinger et al.13 recorded a correlation (r=−0.37) in the validation of the original SCI-R questionnaire itself.

The limitations of our study are related to its design, with no control group allowing for definition of a cause-effect relationship. It would have been unethical for us to have incorporated a control group considering that our team showed coordination and implementation of the TEP to improve the outcomes.5,6 Another limitation is the scant exploitation and analysis of the sociodemographic data. Although analyzed on an individual level for each patient, these data were not used in the TEP analysis.

On the other hand, the strengths of our study are the coordination of the TEP between the pediatric and adult patient teams, the large number of young people transferred, and the periodic evaluation of the program conducted in 20045 and 2013.6 Another aspect to be noted is that a comparison was made according to the type of treatment, namely IP vs. MDI, and also according to the degree of adherence to the self-management of treatment at the start and end of the program, so making it possible for us to define different patient profiles. The effect which real-time continuous glucose monitoring or flash systems – funded by the Spanish National Health System in 2019 – may have upon decision-making, and their impact on improved control of these patients, remain to be established.

Based on the results of this new evaluation, it may be concluded that the TEP remains effective in improving some metabolic control parameters, particularly the reduction of both mild and severe hypoglycemia episodes, as well as knowledge regarding diabetes and eating behavior. The pre- and post-TEP comparison of patients according to type of treatment and the degree of adherence to self-management has served to define different patient profiles that could facilitate the adoption of specific improvement strategies.

The coordination of transfer between the pediatric and adult patient teams continues to be effective, and ensures that all subjects report to the adult hospital. However, an evaluation of the reasons why a number of patients do not complete the program, incorporating the analysis of “patient experience” using qualitative methods, could contribute new knowledge and approaches in this continuity of care model for young people with T1D transferred from Pediatrics to the adult hospital.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Vidal Flor M, Jansà i Morató M, Roca Espino D, Viñals Domenech C, Quirós López C, Mesa Pineda Á, et al. Resultados de un programa específico y estructurado en la transición de pacientes jóvenes con diabetes tipo 1 desde pediatría a un hospital de adultos. La experiencia de una década. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:82–91.