Validate in Spanish the Monitoring Individual Needs in Diabetes Youth Questionnaire (MY-Q), a multi-dimensional self-report HRQoL questionnaire designed for paediatric diabetes care.

Design and methodsAfter translation, 209 patients diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, between 12 and 25 years old were assessed. The patients belonged to 12 hospitals in Spain.

ResultsExploratory factor analysis including one-factor up to seven-factor solutions were tested. The three-factor solution (Negative Impact of Diabetes, Empowerment and Control of Diabetes and Worries) was the most parsimonious model with adequate fit: χ2(723)=568.856 (p<0.001), CFI=0.913, RMSEA=0.072 [0.064, 0.080], SRMR=0.075. The three-factor solution and the grouping of the items followed a clear rationale. Cronbach's alpha was 0.816 for Negative Impact, 0.700 for Empowerment and Control and 0.795 for Worries. The study of the relationship between the MY-Q dimensions and socio-demographics variables show a relationship between age and the MY-Q: F(6,410)=10.873 (p<0.001), η2=0.137. Participants younger than 14 years old showed greater scores on Empowerment and Control when compared to participants between 14 and 17 years old (p=0.021); statistically significant differences were found for the participants 18 years old or older, who showed lower levels of Worries than the younger patients. Concurrent validity found that the dimension of Negative Impact of Diabetes was positively related to WHO-5, and the PedsQL Diabetes Module.

ConclusionThe Spanish version of the MY-Q to measure HRQoL in patients with type 1 diabetes between the ages of 12 and 25, has adequate psychometric properties and conceptual and semantic equivalence with the original version in Dutch.

Validar en español el Monitoring Individual Needs in Diabetes Youth Questionnaire (MY-Q), un cuestionario multidimensional de autoinforme de calidad de vida diseñado para el cuidado de la diabetes pediátrica.

Diseño y métodosDespués de la traducción se evaluaron 209 pacientes con diagnóstico de diabetes tipo 1, entre 12 y 25 años. Los pacientes pertenecían a 12 hospitales de España.

ResultadosSe probaron análisis factoriales exploratorios que incluían soluciones de un factor hasta 7 factores. La solución de 3 factores (impacto negativo, empoderamiento y control y preocupaciones) fue el modelo más parsimonioso con ajuste adecuado: Chi cuadrado (723)=568,856 (p<0,001), CFI=0,913, RMSEA=0,072 [0,064, 0,080], SRMR=0,075. La solución de 3 factores y la agrupación de los ítems siguieron una lógica clara. El alfa de Cronbach fue 0,816 para impacto negativo, 0,700 para empoderamiento y control y 0,795 para preocupaciones. El estudio de la relación entre las dimensiones del MY-Q y las variables sociodemográficas muestra relación entre la edad y el MY-Q: F(6,410)=10.873 (p<0,001), η2=0,137. Los participantes menores de 14 años mostraron mayores puntuaciones en empoderamiento y control en comparación con los participantes entre 14 y 17 años (p=0,021); se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas para los participantes de 18 años o más, quienes mostraron niveles más bajos de preocupaciones que los pacientes más jóvenes. La validez concurrente encontró que la dimensión del impacto negativo de la diabetes se relacionó positivamente con WHO-5 y el módulo de diabetes PedsQL.

ConclusiónLa versión en español del MY-Q para medir la CVRS en pacientes con diabetes tipo 1 entre 12 y 25 años tiene adecuadas propiedades psicométricas y equivalencia conceptual y semántica con la versión original en neerlandés.

Emerging evidence indicates that the Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of children and adolescents with diabetes needs to be assessed not only in clinical research but also in clinical care.1 In fact, assessment of the impact of the disease and its treatment is extremely relevant in clinical practice. In this regard, the International Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) guidelines recommend that an assessment of the developmental progress in all domains of quality of life (i.e., physical, intellectual, academic, emotional, and social development) should be performed routinely.2 In fact, a structured assessment of HRQL followed by respectful discussion of psychosocial problems has shown to be highly appreciated by adolescent patients and to be effective in improving psychological outcomes and satisfaction with care.3,4 For this reason, specific instruments, which are more sensitive to the fluctuations of the disease and provide more detailed information than generic instruments to measure HRQoL1, are needed.

The MY-Q Questionnaire (Mind Youth Questionnaire) is a questionnaire based on a critical review of the existing HRQoL measures for children and young people with type 1 diabetes, with a focus on validity and clinical utility.5 It is the first HRQL questionnaire designed for use in the clinical care of paediatric and adolescent patients with type 1 diabetes.6

The main objective of the MY-Q questionnaire is to gain an understanding of the quality of life of adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) as they experience it themselves, on a physical, emotional, social and mental level. It allows us to open a deliberative dialogue in the healthcare routine and to find out which psychosocial aspects have an influence on the well-being of the individual child/young person in order to develop individualised actions to improve quality of life. It is validated in Dutch in children and adolescents from 10 years of age with T1DM.7 The objective of this study is to carry out a psychometric validation of the MY-Q questionnaire in Spanish for people with T1D between 10 and 25 years of age.

Materials and methodsDesign, setting, and participantsThe validation study was conducted in a sample of 209 patients diagnosed with T1DM, between 12 and 25 years old. The patients came from 12 hospitals in Spain. The questionnaire was administered during a follow-up visit with the endocrinologist or the diabetes nurse. Physicians and nurses that administered the questionnaire were previously trained.

Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were aged between 12 and 25 years, were diagnosed with T1DM, spoke Spanish and gave their informed consent. The exclusion criteria was presenting with severe cognitive problems without adequate socio-family support.

For the sample size calculation, we took into account the recommendation of including a minimum sample size of 100 or 200.8,9

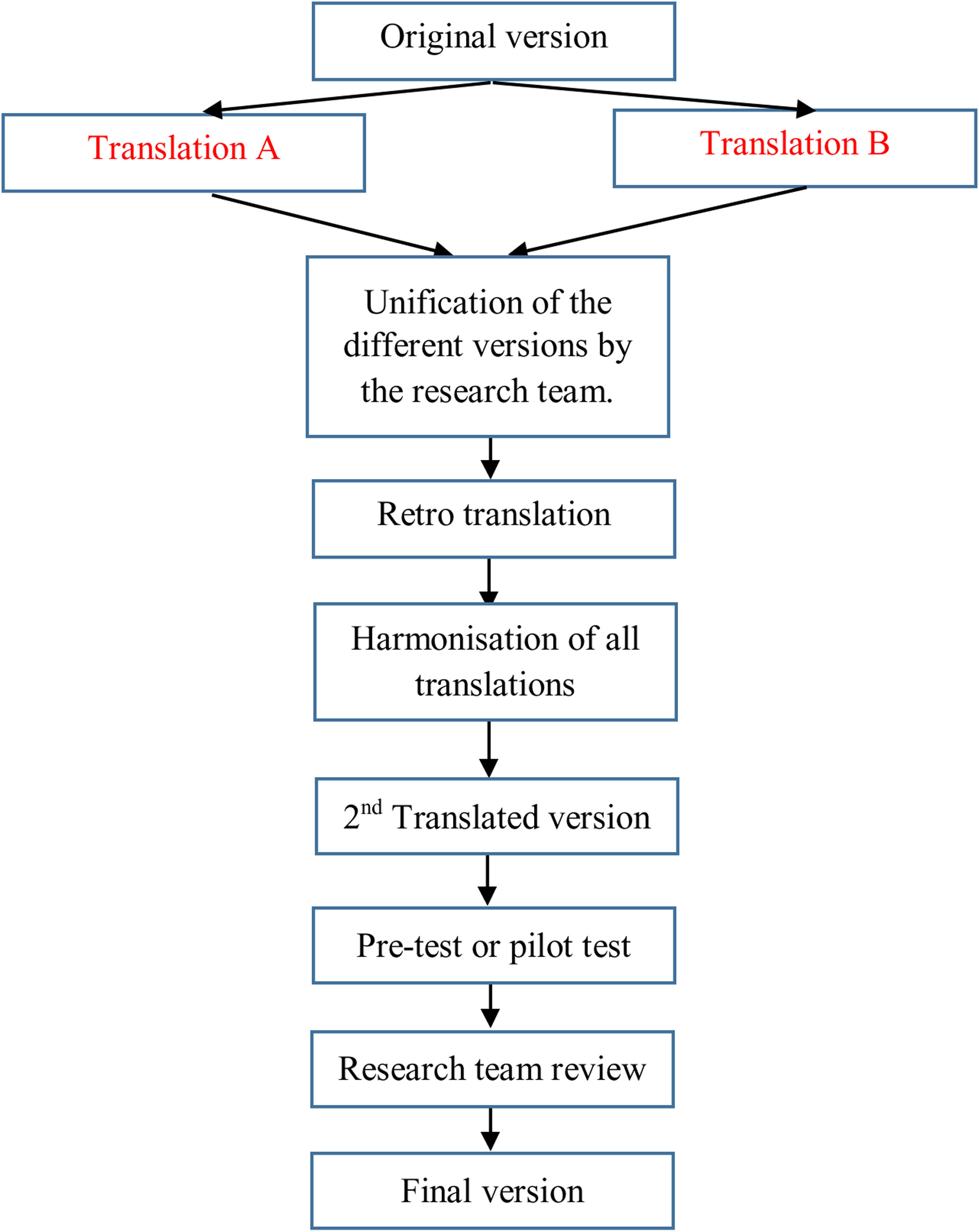

Questionnaire translation and descriptionFor the translation of the questionnaire, the principles of good practices for the translation and cultural adaptation process made by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) working group were taken into account. The stages for the translation were (see Fig. 1):

- a)

Initial preparation and obtaining the authors permission.

- b)

Translation of the original questionnaire into the target language by two independent translators working in the field of health and research (psychologists and nurse).

- c)

Unification of the different versions by the research team.

- d)

Translation of this version back to the original language by two native English translators.

- e)

Comparison and review of the different versions with the original questionnaire by the research team.

- f)

Harmonisation of all translations in order to guarantee conceptual equivalence.

- g)

Pilot test: the translated questionnaire was delivered to 10 patients for their evaluation. A support text was included in order to collect any doubts that could be raised with any question regarding comprehension and writing, and to proof the global assessment of the questionnaire by the patients.

- h)

The results of the pilot test were analysed and the translation was finalised by the research team.

- i)

Editing the questionnaire.

The MY-Q consists of 36 items: a general question, 27 items on different domains of quality of life, five items corresponding to the WHO-5 questionnaire and three open questions. MY-Q covers the domains of General QoL: social life (friends, family, and school), diabetes management (worries, treatment barriers, self-efficacy and satisfaction, and problematic eating), and emotional well-being. Most questions use a Likert scale, indicating frequency or intensity.

The MY-Q starts with a general QoL item that asks how teenagers rate their overall life on a 10-point ladder (1=worst life possible to 10=best life possible). The raw scores are transformed to 1–100. This question is then followed by 27 items on generic and diabetes-related well-being, scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1=all the time to/5 never/1=never to 5=11–14 d).

Data collectionSeveral socio-demographic data and diabetes-related variables were collected, including age, gender, diabetes duration, main treatment.

In addition to the MY-Q, quality of life was measured using the well-being (WHO-5)10 and the diabetes-specific module of the PedsQL, which includes 28 questions regarding diabetes.11

Data analysisFirst, the factor structure of the MY-Q was studied. The internal structure was analysed using exploratory factor analysis (EFA). According to the ordinal nature of the data and its non-normality, the estimation method was weighted least square mean and variance-adjusted (WLSMV). Promax rotation was used. Model fit was assessed using the chi square statistic, the CFI, with values of more than 0.90 (ideally 0.95) indicating good fit, and the RMSEA, with values of 0.08 or less for an excellent fit.12 For estimations of internal consistency, Cronbach's alphas were computed. Furthermore, we studied the relation between the Spanish version of the MY-Q and sex and age, using multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA). Finally, concurrent validity was assessed by relating the dimensions of the MY-Q to WHO-5 (well-being) and Diabetes Module PedQL (quality of life in children and teenagers with diabetes), using Pearson correlations.

The analyses were performed with Mplus 8.113 and SPSS version 27.14

Ethical considerationsThe evaluation protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Research of the University of Valencia (Number: UV-INV_ETICA-1570125) and the Ethics and Clinical Research Committee of the Vall d’Hebrón University Hospital in Barcelona with number PR(AG)212/2021.

ResultsIn order to study the internal structure of the Spanish version of the MY-Q, an exploratory factor analysis including one-factor up to seven-factor solutions were tested. Overall fit was inadequate for the one- and two-factor solutions (see Table 1). The three-factor solution showed adequate fit: χ2(723)=568.856 (p<0.001), CFI=0.913, RMSEA=0.072 [0.064, 0.080], SRMR=0.075, as well as the four-, five-, six-, and seven-factor solutions. Because the three-factor solution was the most parsimonious model with adequate fit, and the grouping of the items followed a clear rationale that will be explained in the next lines, this model was retained.

Exploratory factor analysis models’ overall fit.

| Model | χ2 | d.f. | p | CFI | RMSEA [90% CI] | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One factor | 1297.332 | 324 | <0.001 | 0.714 | 0.120 [0.113, 0.127] | 0.134 |

| Two-correlated factors | 831.674 | 298 | <0.001 | 0.843 | 0.093 [0.086, 0.100] | 0.095 |

| Three-correlated factors | 568.856 | 273 | <0.001 | 0.913 | 0.072 [0.064, 0.080] | 0.075 |

| Four-correlated factors | 467.834 | 249 | <0.001 | 0.936 | 0.065 [0.056, 0.074] | 0.065 |

| Five-correlated factors | 384.076 | 226 | <0.001 | 0.954 | 0.058 [0.048, 0.068] | 0.056 |

| Six-correlated factors | 314.719 | 304 | <0.001 | 0.967 | 0.051 [0.040, 0.062] | 0.049 |

| Seven-correlated factors | 268.702 | 183 | <0.001 | 0.975 | 0.047 [0.035, 0.059] | 0.042 |

Notes: Italics for the model retained.

The analytical fit of the three-factor model is displayed in Table 2. As shown in the table, factor one, or the “Negative Impact of Diabetes” factor, grouped items related to obstacles, barriers, communication problems, handling, etc. Factor two, or the “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” factor, grouped items related to feelings about treatment control, self-efficacy and competence. Finally, factor three, or the “Worries” factor, was formed by items 28 and 29, related to diabetes specific concerns. Only two items showed some particularities in their behaviour. Item 12, although related to “Negative Impact of Diabetes”, had a higher, negative factor loading in the “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” factor. However, as theoretically better described behaviours grouped in the factor “Negative Impact of Diabetes”, we decided to retain it in this factor. Item 4 “I get along well withcolleagues”, in turn, showed very low factor loadings in the three factors. Indeed, it is not clearly related to either “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” or “Negative Impact of Diabetes”, since taking care of having an adequate weight is considered a healthy habit as long as pathological behaviours are not engaged in, something that is not reflected in the wording of the item. Therefore, we decided to remove this item from the Spanish version of the MY-Q. Taking into account this rationale, we grouped the items in the three factors as shown in Table 3.

Factor loadings and descriptive statistics for the MY-Q items.

| Item | λFactor1 | λFactor2 | λFactor3 | M | SD | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.493 | 0.390 | 0.081 | 64.23 | 23.846 | 0 | 100 |

| 2 | 0.133 | 0.373 | 0.085 | 63.04 | 33.80 | 0 | 100 |

| 3 | 0.715 | 0.449 | 0.009 | 70.69 | 26.62 | 0 | 100 |

| 4 | 0.242 | 0.460 | −0.033 | 89.47 | 17.59 | 0 | 100 |

| 5 | 0.725 | 0.449 | −0.020 | 83.73 | 24.61 | 0 | 100 |

| 6 | 0.798 | 0.495 | −0.012 | 58.01 | 24.97 | 0 | 100 |

| 7 | 0.711 | 0.138 | −0.073 | 68.78 | 31.64 | 0 | 100 |

| 8 | 0.727 | 0.405 | 0.012 | 59.57 | 28.45 | 0 | 100 |

| 9 | 0.804 | 0.365 | 0.004 | 72.97 | 24.98 | 0 | 100 |

| 10 | 0.713 | 0.339 | −0.159 | 77.15 | 28.08 | 0 | 100 |

| 11 | 0.332 | 0.689 | 0.080 | 92.22 | 18.08 | 0 | 100 |

| 12 | 0.288 | −0.411 | 0.180 | 22.73 | 26.36 | 0 | 100 |

| 13 | 0.457 | 0.048 | −0.023 | 71.17 | 31.54 | 0 | 100 |

| 14 | 0.567 | 0.015 | −0.032 | 61.84 | 34.33 | 0 | 100 |

| 15 | 0.562 | 0.054 | −0.060 | 57.89 | 31.26 | 0 | 100 |

| 16 | 0.632 | 0.333 | 0.218 | 47.25 | 28.61 | 0 | 100 |

| 17 | 0.491 | −0.266 | 0.016 | 45.33 | 33.15 | 0 | 100 |

| 23 | 0.369 | 0.454 | −0.133 | 73.68 | 26.65 | 0 | 100 |

| 24 | 0.092 | 0.223 | 0.068 | 57.54 | 33.43 | 0 | 100 |

| 25 | 0.546 | 0.489 | 0.009 | 77.51 | 21.71 | 0 | 100 |

| 26 | 0.708 | 0.618 | −0.083 | 95.33 | 12.94 | 25 | 100 |

| 27 | 0.537 | 0.604 | 0.192 | 59.33 | 37.85 | 0 | 100 |

| 28 | −0.100 | −0.211 | 0.748 | 41.51 | 30.66 | 0 | 100 |

| 29 | −0.051 | −0.052 | 0.907 | 41.03 | 32.25 | 0 | 100 |

| 30 | 0.490 | 0.768 | −0.019 | 87.08 | 20.52 | 0 | 100 |

| 31 | 0.375 | 0.571 | 0.178 | 64.35 | 24.58 | 0 | 100 |

| 32 | 0.406 | 0.875 | −0.119 | 85.65 | 21.02 | 0 | 100 |

Notes: λ=f factor loading; M=mean; SD=standard deviation; Min=minimum score; Max=maximum score. Italics factor loadings indicate the factor in which the item is retained. Items scores are recoded (1=0, 2=25, 3=50, 4=75, and 5=100) and the total score computed as a mean of the items, resulting in scores between 0 and 100.

Structure of the MY-Q in Spanish: items and factors.

| Item | Negative impact of diabetes | Empowerment and control of diabetes | Worries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Es difícil prestar atención en clase.It's hard to pay attention in class. | X | ||

| 2 | Puedo confiar en que mis profesores se encargarán de mi diabetes cuando fuera necesario I can trust my teachers to take care of my diabetes when necessary | X | ||

| 3 | ¿Con qué frecuencia la diabetes es un obstáculo en su vida social, amistades y relaciones?How often is diabetes an obstacle in your social life, friendships, and relationships? | X | ||

| 4 | Otros niños me intimidanOther kids bully me | X | ||

| 5 | ¿Con qué frecuencia la diabetes interfiere con su tiempo libre?How often does diabetes interfere with your free time? | X | ||

| 6 | ¿Tu diabetes te impide hacer cosas sin tus padres? (fiestas, quedar, …)Does your diabetes keep you from doing things without your parents? (parties, meet, …) | X | ||

| 7 | ¿Con qué frecuencia interfiere la diabetes con sus actividades deportivas (por ejemplo, fútbol, tenis)?How often does diabetes interfere with your sports activities (e.g., soccer, tennis)? | X | ||

| 8 | ¿Con qué frecuencia la diabetes le obstaculiza cuando empieza a hacer algo con la familia?How often does diabetes get in the way when you start doing something with your family? | X | ||

| 9 | ¿Con qué frecuencia siente que su diabetes está molestando a los miembros de su familia? (tus padres, hermanos, hermanas o abuelos)How often do you feel like your diabetes is bothering your family members? (your parents, brothers, sisters, or grandparents) | X | ||

| 10 | ¿Con qué frecuencia sientes que tus padres te han dado suficiente ayuda y apoyo para controlar su diabetes?How often do you feel that your parents have given you enough help and support to manage your diabetes? | X | ||

| 11 | ¿Con qué frecuencia sientes que tus padres se preocupan demasiado por su diabetes?How often do you feel that your parents worry too much about your diabetes? | X | ||

| 12 | ¿Con qué frecuencia sientes que tus padres fingen que es su diabetes?How often do you feel that your parents act like it's their diabetes? | X | ||

| 13 | En el último mes, mis padres y yo tuvimos desacuerdos sobre recuerda revisar mi azúcar en sangreIn the last month, my parents and I had disagreements about remembering to check my blood sugar | X | ||

| 14 | En el último mes, mis padres y yo tuvimos desacuerdos sobre comidas y snacks?In the last month, my parents and I had disagreements about meals and snacks? | X | ||

| 15 | ¿Con qué frecuencia sientes que tienes que hacer demasiado por tu tratamiento de la diabetes?How often do you feel like you have to do too much for your diabetes treatment? | X | ||

| 16 | ¿Con qué frecuencia sientes que otros hacen mucho para tu tratamiento de diabetes?How often do you feel that others are doing a lot for your diabetes treatment? | X | ||

| 17 | Estoy satisfecho con mi aparienciaI am satisfied with my appearance | X | ||

| 23 | Intento (de diferentes formas) influir en mi pesoI try (in different ways) to influence my weight | X | ||

| 24 | ¿Cuántas veces en los últimos 14 días ha comido en exceso?How many times in the last 14 days did you overeat? | X | ||

| 25 | ¿Cuántas veces en los últimos 14 días se saltó la insulina a propósito?How many times in the past 14 days did you skip your insulin on purpose? | X | ||

| 26 | Siento que tengo el control de mi diabetesI feel like I’m in control of my diabetes | X | ||

| 27 | ¿Con qué frecuencia te preocupas por tener una hipoglucemia grave?How often do you worry about having severe hypoglycaemia? | X | ||

| 28 | ¿Con qué frecuencia te preocupas por tener complicaciones por la diabetes?How often do you worry about complications from diabetes? | X | ||

| 29 | ¿Está satisfecho con su equipo de diabetes?Are you satisfied with your diabetes team? | X | ||

| 30 | ¿Está satisfecho con los valores de azúcar en sangre que obtiene?Are you satisfied with your blood sugar values? | X | ||

| 31 | ¿Está satisfecho con el tratamiento médico que está recibiendo actualmente?Are you satisfied with the medical treatment you are currently receiving? | X |

The estimates of reliability for the factors were calculated. For the “Negative Impact of Diabetes” factor, Cronbach's alpha was 0.816; for the “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” factor, the estimate of reliability was 0.719; and for the “Worries” factor, Cronbach's alpha was 0.795.

Levels of diabetes-related quality of life are detailed in Table 2. For the “Negative Impact of Diabetes” (F1) dimension, items with higher scores were 26 (95.33) and 11 (92.22); lower scores were observed for item 12 (22.73). For the dimension of “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” (F2) factor, there were higher scores for items 4 (89.47), 30 (87.08), and 32 (85.65), and lower scores were observed for item 27 (59.33). Finally, for the dimension of “Worries” (F3) factor, items showed almost identical scores.

Regarding the dimensions themselves, the mean in the “Negative Impact of Diabetes” dimension was 61.29, pointing to medium-high levels of negative impact of diabetes or distress on the life of the patient. For the “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” dimension, the mean was 76.85. Taking into account that this factor is formed by reversed items, this result clearly points to low levels of control related to patients’ self-efficacy regarding diabetes. Finally, for the “Worries” (F3) dimension, the mean was 41.27; therefore, levels in this dimension were medium-low (Table 4).

Levels of the MY-Q for the general sample and the subgroups under study.

| Factor1 | Factor2 | Factor3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Total sample | 61.29 | 15.02 | 76.85 | 15.08 | 41.27 | 28.67 |

| By gender | ||||||

| Men | 62.03 | 14.01 | 78.36 | 14.69 | 43.28 | 28.41 |

| Women | 60.70 | 15.81 | 75.65 | 15.33 | 39.66 | 28.90 |

| By age | ||||||

| <14 years old | 60.49 | 15.26 | 83.04 | 11.98 | 46.00 | 30.14 |

| 14–17 years old | 60.42 | 13.47 | 76.65 | 13.90 | 48.04 | 26.12 |

| >17 years old | 63.19 | 16.35 | 69.82 | 16.56 | 28.32 | 25.51 |

To study the relationship between the MY-Q dimensions and sex, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was calculated, in which sex was the independent variable, and the dimensions of the MY-Q were the dependent variables. The MANOVA resulted in not being statistically significant: F(3, 205)=0.879 (p=0.453), η2=0.013. The follow-up ANOVAs did not point to statistically significant differences in the specific dimensions: F(1, 207)=0.406 (p=0.525), η2=0.002, for the “Negative Impact of Diabetes” factor; F(1, 207)=1.678 (p=0.197), η2=0.008, for the “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” factor; and F(1, 207)=0.824 (p=0.365), η2=0.004, for the “Worries” factor. When means were compared, males and females showed similar scores in the three dimensions (see Table 4). A second MANOVA was calculated to study the relationship between age and the MY-Q. This analysis was statistically significant: F(6, 410)=10.873 (p<0.001), η2=0.137. The follow-up ANOVAs pointed to statistically significant differences in the specific dimensions of “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” (F2) (F(2, 206)=15.081 (p<0.001), η2=0.128) and “Worries” (F3) (F(2, 206)=10.355 (p<0.001), η2=0.091), but not for “Negative Impact of Diabetes” (F1) (F(2, 206)=0.734 (p=0.481), η2=0.007). For the dimension of “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” (F2), post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni corrections pointed to statistically significant differences across the three age groups: participants younger than 14 years old showed greater scores on “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” when compared to participants between 14 and 17 years old (p=0.021). Participants between 14 and 17 years old showed greater scores on “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” when compared to participants older than 17 years old (p=0.017). Taking into account that this factor has reversed scores, this means that the older the participant, the more “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” there was (see descriptive statistics in Table 4). For the dimension of “Worries” (F3), post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni corrections pointed to statistically significant differences for the participants aged 18 years old or older, who showed lower levels of “Worries” (F3) when compared both to participants younger than 14 years old (p=0.001) and to participants between 14 and 17 years old (p<0.001) (see Table 4). No statistically significant differences were found between these last age groups.

Finally, concurrent validity was assessed by relating the dimensions of the MY-Q to WHO-5 (well-being) and Diabetes Module PedQL (quality of life in children and teenagers with diabetes). The dimension of “Negative Impact of Diabetes” (F1) was positively related to WHO-5, and negatively to the dimensions of the PedQL (for specific values, see Table 5). This indicates that when the patient obtains a high score in this dimension, they present worse emotional well-being (WHO-5) and worse quality of life related to diabetes (PedQL). The dimension of “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” (F2), showed the same pattern of associations: high scores on this dimension imply worse emotional well-being. Finally, the Worries (F3) dimension, was only statistically and negatively related to the “Worry” factor in the PedQL.

Correlations among the MY-Q dimensions and WHO-5 and PedsQL.

| F1 Negative impact | F2 Empowerment | F3 Worries | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General QoL | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.633 |

| WHOTotal | 0.537** | 0.680** | 0.077 |

| PedQProblems | 0.573** | 0.482** | 0.113 |

| PedQTreatment1 | 0.701** | 0.539** | −0.130 |

| PedQTreatment2 | 0.555** | 0.597** | −0.129 |

| PedQWorry | 0.198*** | 0.228** | 0.489** |

| PedQCommunication | 0.565*** | 0.450** | 0.024 |

| PedQTotal | 0.704** | 0.620** | 0.047 |

The Spanish version of the MY-Q to measure HRQoL in children and adolescents with T1DM between the ages of 12 and 25 presents adequate psychometric properties and conceptual and semantic equivalence with the original version in Dutch. This study is the first approach to assess the self-perceived health of children, adolescents and young adults with T1DM in Spain with a specific questionnaire that includes multiple psychosocial areas and not only aspects of the disease. PRO assessment with follow-up by the health care provider has been shown to positively influence well-being and satisfaction with care in young people with T1DM.15–17 Despite these recent developments and recommendations of the use of PROs in clinical care,18–20 the literature on integration of PROs in diabetes clinical care is relatively new. An instrument like MY-Q might facilitate a conversation putting the patient perspective at the centre.

The linguistic adaptation process allowed us to obtain a comparable instrument that maintains conceptual and semantic equivalence, which is now appropriate for the Spanish population. When the questionnaires were applied, correct functionality was appreciated and the population easily understood it. On the metric criteria it can be self-administered or conducted through a personal interview. The response rate was 100%. The scores are distributed along the amplitude of the measurements, the results being comparable to the original study in Dutch.7

The structure of the questionnaire was different from the original, which was obtained through an exploratory factor analysis. In the analyses carried out in this study, a 3-factor solution was found to explain 64.40% of the total variance. Overall, the validity and reliability of the MY-Q turned out to be robust. The reliability assessed through Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the validated version was good for the three factors.

To summarise the results of the questionnaire, there were no statistically significant differences regarding gender, although men presented slightly higher scores than women. However, differences were found in terms of age: participants younger than 14 years old showed greater scores on “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” when compared to participants between 14 and 17 years old. Additionally, participants between 14 and 17 years old showed greater scores on “Empowerment and Control of Diabetes” when compared to participants older than 17 years old. Regarding “Worries”, the older patients have lower scores on this factor. In this regard, it should be noted that the link between quality of life and some of the clinical variables studied is complex and not necessarily linear: patients who do not accept the introduction of changes to their lifestyle, such as exercising or adhering to a diet could have better quality of life but worse metabolic control.

In this study, the questionnaire has shown that it maintains the expected relationships with other quality of life questionnaires such as the WHO-5 and the PedsQL. The construct validity has allowed us to advance that this questionnaire can go beyond a measure of the patient's health status, but rather identify the areas of intervention.

The original questionnaire is aimed at patients between 10 and 18 years old. This work has taken into account patients between 12 and 25 years of age, due to the similarities that adolescents and post-adolescents (young adults) present in the Spanish context. The decision to include patients over 12 years of age was due to a maturation issue, so that the language and questions related to diabetes management could be used for the entire age spectrum considered. In addition, in the educational system 12 years is the age at which the passage from primary to secondary education occurs.

One of the limitations of the present study is the need for additional research to examine the test-retest reliability and sensitivity over time of the MY-Q in longitudinal studies and trials. It would also be interesting to take into account aspects such as acceptability and readability as they could be sensitive to educational level and cultural differences and therefore deserve special attention.

The most widespread criticism of the existing questionnaires that measure the quality of life in children and/or adolescents such as the DQOLY-SF,21 refers to the impossibility to relate the impact of the self-care required to the treatment of diabetes with development and social evolution, affective and physical of the patients. The Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) Diabetes10 is a modular instrument for measuring health-related quality of life in children and adolescents aged 2 to 18 years. It is a validated instrument, with an easy and rapid applicability and is structured by evolutionary stages. One of its weaknesses is that it does not delve into two basic aspects of the daily habits of children and adolescents: diet and physical exercise. The MY-Q overcomes this limitation. Other questionnaires, such as the KIDSCREEN-52,22 have been used to assess the impact of diabetes on quality of life in adolescents, but they are not specific instruments for this condition. By contrast, each item of the MY-Q assesses an important aspect of living with diabetes. Quality of life interventions can specifically target risk areas, making it easier for healthcare professionals who are not psychosocial specialists to provide meaningful assistance to their own patients or refer them to another professional with a specific intervention request. For example, the MY-Q can help lower the threshold for detecting eating disorders, prompting a conversation with a paediatrician or nurse educator. If indicated and agreed upon, an early referral can be initiated for a more extensive clinical evaluation.

Regular monitoring of HRQoL provides the opportunity to track changes over time and examine the impact of treatment both at an individual and a group level. The MY-Q questionnaire provides a single source of new data to explore associations between psychosocial and clinical outcomes over time in T1DM patients.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.