Smoking is, together with diabetes mellitus, one of the main risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Diabetic patients have unique features and characteristics, some of which are not well known, that cause smoking to aggravate the effects of diabetes and impose difficulties in the smoking cessation process, for which a specificand more intensive approach with stricter controls is required. This review details all aspects with a known influence on the interaction between smoking and diabetes, both as regards the increased risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications of diabetes and the factors with an impact on the results of smoking cessation programs. The treatment guidelines for these smokers, including the algorithms and drug treatment patterns which have proved most useful based on scientific evidence, are also discussed.

El tabaquismo es, junto con la diabetes mellitus, uno de los principales factores de riesgo cardiovascular. Los pacientes diabéticos presentan peculiaridades y características, algunas no bien conocidas, que hacen que el tabaquismo agrave los efectos de la diabetes y que el proceso de la deshabituación tabáquica en estos pacientes presente dificultades añadidas y que, por tanto, requiera un abordaje específico, más intensivo y con controles más rigurosos. En esta revisión se desgranan todos los aspectos conocidos que influyen en la interacción entre el tabaquismo y la diabetes, tanto en lo referente al incremento del riesgo de las complicaciones macrovasculares y microvasculares de la diabetes como a los factores que influyen en los resultados de los programas de deshabituación tabáquica. Así mismo se exponen las pautas de tratamiento de estos fumadores, incluyendo los algoritmos y pautas de tratamiento farmacológico que, basándose en evidencia científica, se han mostrado más eficaces.

Since 2008, the main clinical practice guidelines on smoking, “Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence, 2008 Update”,1 of the United States Public Health Service, have identified smoking as a chronic addiction, though the World Health Organization (WHO) continues to include smoking in its International Classification of Diseases (ICD)2 within the group of Mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F17). The recognition of chronicity is not a minor issue, since as the guidelines point out, repeated interventions and multiple cessation attempts are often required to control the condition.1 Smoking is also regarded as a risk factor for many diseases, mainly respiratory, cardiovascular and neoplastic. Although less known, smoking may also have an impact on the behavior of diabetes and its vascular complications.3

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), smoking is the leading cause of avoidable disease and mortality in the United States.4 However, the percentage of smokers decreased from 20.9% in 2005 to 15.1% in 2015, while daily smokers decreased from 16.9% to 11.4%.4 Tobacco smoking has also decreased in Spain in recent years.

Few data are available on the prevalence of smoking among diabetic patients. In a German study pooling data from two large trials, Schipf et al. concluded that the percentage of active smokers was somewhat lower in diabetics than in non-diabetics, with figures of 20%–35% in males and 10%–30% in females.5

Classical studies such as that published by Bott et al., involving 700 type 1 diabetics, concluded that smoking is one of the strongest predictors of poor metabolic control.6

Smoking is related as an etiological factor to the development of type 2 diabetes because of the influence it has in modifying insulin receptor sensitivity, and also as a triggering or aggravating factor of the vascular complications of diabetes.7There are studies suggesting that patients with diabetes who smoke have high morbidity and mortality risks mainly associated with macrovascular complications of the disease.8,9 Other publications relate smoking to early microvascular complications.10 Smoking cessation is therefore considered to be an essential factor in preventing adult diabetes and its complications.

The exact nature of the interaction between smoking and diabetes is little known, but has been a cause of concern for years. Soulimane et al., in a meta-analysis published in 2014, reported that smokers have higher glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels and lower two-hour plasma glucose (2H-PG) levels than non-smokers. This difference is also seen between smokers and ex-smokers, though the clinical significance of these findings is still unclear.11

Biochemical insulin-nicotine interactions and metabolism in diabetic patientsIt has long been hypothesized that smoking decreases insulin sensitivity, and that this effect may be mediated by nicotine through the stimulation of insulin-antagonizing substances such as cortisol, catecholamines, and growth hormone.12 Other mechanisms that may influence the development of diabetes as side effects of nicotine have been reported, including the inhibition of gastric motility and its influence upon the differentiated emptying of solids and liquids,13,14 faster glucose absorption,15 and increased erythrocyte permeability to glucose.16 However, Wareham et al. considered a causal relationship unlikely, since the importance of smoking was attenuated after adjusting the results for age and the body mass index (BMI).17 No direct relationship has been shown between altered insulin secretion and smoking.12 It is also likely that smokers have other unhealthy habits, or that eating habits or a low socioeconomic status (known risk factors for diabetes) may act as confounding factors.

Only a few studies have found a relationship between smoking and body weight in diabetic smokers. Such patients tend to express concern about gaining weight after smoking cessation and its influence on insulin therapy.18 Some diabetic smokers see tobacco consumption as a tool to control weight, and are worried that smoking cessation may have an adverse effect upon diabetes control.

In their meta-analysis, Farley et al. concluded that the drugs most commonly used for smoking cessation – bupropion, varenicline, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and fluoxetine – reduce weight gain during active drug treatment, but have not been shown to maintain this effect after one year.19 These authors also found that individual patient education for weight control is not effective: indeed, the abstinence rate was even seen to decrease. In addition, very low-calorie diets do not prevent weight gain over the long term. Physical exercise was the only measure shown to decrease body weight over the long term in this meta-analysis.19

The relationship between smoking and a lower BMI has been investigated, and is known to be one of the main reasons why some patients delay or avoid smoking cessation. The CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 genes are strongly associated with the amount of tobacco consumed by smokers. The copies of these genes usually increase in number with the level of consumption, but their relation to the BMI was until recently unknown. Freathy et al. concluded that there is no association between the abovementioned genes and the BMI in non-smokers, while the presence of allele changes in these genes in smokers and ex-smokers implies a greater decrease in the BMI in the former.20 An additional conclusion of this article was that after long-term abstinence, the BMI of ex-smokers is almost equal to that of non-smokers. This should be taken into account when dealing with the problem of smoking in such patients, in order to encourage strict diet control and increased physical exercise. It should not be forgotten that weight gain is one of the causes of relapse in all kinds of smokers, particularly women. In any case, weight gain is a minor risk as compared to continued smoking.18

Lycet et al. reported that, in diabetics, smoking cessation is associated with poorer blood glucose control, which results in increased HbA1c values,21 but other authors such as Taylor et al. have queried these findings because of the presence of confounding factors, and suggest the need for studies on larger population samples.22 The main confounding factor again may be the weight increase seen occurring after smoking cessation and its impact on blood glucose control. In any case, it should be emphasized that the benefits of smoking cessation clearly outweigh any associated negative effects there may be.

Some studies suggest that the reward mechanism may be altered in diabetic patients who smoke due to little known interactions between insulin and dopamine. This could explain why diabetic smokers find it more difficult to quit the habit, and could warrant the adoption of more intensive interventions in these individuals.23 Treatment of smoking with drugs that increase dopamine levels in the mesolimbic region, such as bupropion, could therefore be particularly indicated in these patients.

Genetics, smoking and diabetesSmoking and its associated morbidity and mortality are among the most important social and health problems, and are particularly important in diabetic subjects. The development, maintenance, and cessation of smoking habits are related to susceptibility genes, ranging from classical Mendelian hereditary traits to complex polygenic hereditary patterns.24

There is abundant evidence in the literature linking genes related to nicotine metabolism, such as the CYP2D6, CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 genes, to smoking cessation difficulty. The latter has been postulated as a marker of the severity of withdrawal symptoms and of relapse that can be modified with drug substances such as bupropion.24

The main action site of nicotine is the central nervous system, where it acts upon neuronal receptors, modifying the neurotransmission systems.24 There is abundant evidence regarding the pathways related to nicotine addiction, including in particular the dopaminergic pathway. Some of the genes most widely studied in relation to tobacco addiction are those that regulate dopamine flow within the central nervous system. Nicotine increases dopamine production and release and stimulates the metabolism in the basal ganglia. The genes studied at this level are those that encode for the five dopamine receptors, which are referred to as DRD with the respective number.

The serotonergic system is particularly involved in mood changes. Nicotine increases serotonin secretion, while its absence lowers secretion. This has been related to the mood swings that characterize the smoking cessation process.

In recent years, nicotine receptors have been postulated as important factors in the modulation of nicotine addiction.25 The CHRNA5 nicotine receptor gene has been identified as an important indicator of dependence. Many studies have shown and explained that variations of this gene may influence a greater or lesser difficulty in quitting smoking or the susceptibility to start smoking.

An additional important issue is the impact of smoking upon methylation. The reference study in this regard was published by Zeilinger et al., who were the first to demonstrate that smoking causes significant changes in the gene methylation pattern.26 Other studies have found changes even in the offspring of smoking women, with methylation being found to be dose-dependent.27

With regard to the increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes from the genetic viewpoint and in relation to methylation, Ligthart et al. attempted to link diabetes-related genes to the changes induced by smoking in such genes. They concluded that, in the study subjects, it was smoking which induced changes in methylation of the ANPEP, KCNQ1, and ZMIZ1 genes, which are relevant for the development of diabetes.28

Besingi et al. in turn raised the study of methylation to another level, since they investigated molecular functions, not only isolated gene regions. These authors found in the insulin receptor several gene regions with different methylation patterns (PTPN11, GRB10, ENPP1, IGF1R).29 Methylation could alter the insulin receptor, causing insulin resistance and increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes. This molecular function is of particular interest because, as previously discussed in this article, previous studies had already suggested that smoking is a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes, and this finding reported by Besingi et al. provides a satisfactory explanation at the molecular level.3 These authors also noted that these changes in methylation were not permanent, as changes were seen in some samples after smoking cessation. This would further justify antismoking interventions in these patients.29 Finally, another described process was the negative regulation of glucose transporters. However, while this is a very promising field, further studies are needed.

Other studies have focused on the relationship between smoking and telomere length. Telomeres are hexameric regions characterized by repetition of the nucleotide sequence TTAGGG in the distal portion of the chromosomes. They act as buffers during cell division, preventing replication of the final portion. As a result, telomeres shorten with advancing age. Smoking is associated with telomere shortening and with increased mortality for any cause. Rode et al. explored the causal relationships underlying the abovementioned phenomena. For this, they determined telomere length, tobacco consumption, and the CHRNA3 genotype, which is closely related to smoking, in 55,568 Danish subjects. A causality study was subsequently made to find out the relationship between these factors. These authors concluded that smoking is causally related to increased all-cause mortality, but did not find any causal relationship between smoking and telomere shortening. Such shortening therefore does not mediate the relationship between smoking and increased mortality, or at least it is not the only mediating factor.30

Macrovascular and microvascular complications in diabetic patientsBoth type 1 and type 2 diabetes have long been known to be associated with excess morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular diseases, and smoking exerts a strong impact in this regard. In the Sowers et al. study,31 not even the hormone-mediated protective effect in women could slow the advance of cardiovascular disease in diabetic patients.

Oxidative stress plays a key role as a mechanism of damage after smoking. In 1992, the Danish group led by Loft et al.32 first mentioned the oxidative stress caused by smoking and the resultant damage to deoxyribonucleic acid.

The Ellegaard et al. meta-analysis33 comprised 36 studies, some of which reported a direct relationship, while others did not. Following the pertinent statistical studies, this meta-analysis showed a significant difference in deoxyribonucleic acid oxidative stress between smokers and non-smokers. The difference was approximately 15%. Overall analysis of the study data, referring to more than 5377 patients, provides strong evidence of the relationship between smoking and oxidative stress.

As regards macrovascular complications, Meigs et al.34 found in 1500 type 2 diabetics that active smokers were 1.54-fold more likely to have coronary problems than non-smokers. Another study conducted on a prospective cohort followed up for 16 years found tobacco smoking to be an independent predictor of stroke in these patients.35

In a cohort of approximately 4500 diabetic patients, Chaturvedi et al.36 analyzed mortality according to smoking history and the date of smoking cessation. They concluded that subjects who had smoked but quit more than 10 years previously had a 25% higher mortality risk than those who had never smoked, but a markedly lower risk than those who had quit smoking less than 10 years previously. Thus, smoking increases macrovascular morbidity and mortality in diabetic patients, and this risk persists for more than 10 years after smoking cessation.36

Nephropathy in type 1 diabetics and microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetics are the issues that have drawn most attention in the literature. Ikeda et al.37 studied 148 diabetic patients and concluded that the incidence of microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria was greater in active smokers (53%) as compared to ex-smokers (33%) and non-smokers (20%).

Another prospective study monitored a cohort of 231 patients without symmetrical distal polyneuropathy for five years and found the incidence of neuropathy to be 2.2-fold higher in smokers as compared to non-smokers. Moreover, in patients who already had neuropathy, smoking increased its development 12-fold.38

As already pointed out by Klein et al.,39 most epidemiological studies have found no relationship between smoking and retinopathy, though there are exceptions.

Reichard et al.40 found a relationship between tobacco smoking and the progression of microvascular complications in 96 type 1 diabetics followed up for five years and randomized to either intensive or conventional therapy. The authors found the progression of retinopathy to be accelerated by smoking and the glycosylated hemoglobin level. Muhlhauser et al.41 also reported a significant relationship between smoking, retinopathy, and nephropathy.

To sum up, many studies suggest that tobacco smoking has an impact on the development and progression of microalbuminuria and impaired kidney function in type 1 and type 2 diabetics. Other studies also suggest an association with diabetic neuropathy and retinopathy.

Specific procedures to help diabetic patients quit smokingAlthough only limited information is available in the literature on the effectiveness of smoking cessation methods in diabetic patients, two important studies are discussed below. Ardron et al. conducted a randomized study of 60 diabetic smokers comparing brief advice versus intensive advice.42 Half the patients given intensive advice attempted smoking cessation at least once, but at the end of the six months of follow-up, only one patient had quit smoking. Sawicki et al. also compared behavioral therapy applied for 10 weeks to brief advice for 15min. The mean number of cigarettes smoked decreased in the intensive intervention group, but after six months of follow-up, the cessation rates were the same in both groups.43

Most articles on diabetes and smoking focus on literature reviews and extrapolate the data they contain. Based on the little information available, it may be concluded that the results of treatment and interventions are slightly poorer than in non-diabetic patients, and a greater number of intensive treatments should therefore be performed. Additional studies are needed to identify and understand the factors associated with the management of diabetes and their influence on smoking cessation.

Despite the above, there are general recommendations, such as the Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes of the American Diabetes Association (ADA),9 which include the recommendation to intervene against smoking in order to prevent cardiovascular risk in diabetic patients. Guidelines are also provided by the 2005 consensus document on the management of diabetic patients of the Group for the Study of Diabetes in Primary Care and the Spanish Society of Cardiology,8 which state that all diabetic patients should be recommended to refrain from smoking and that counseling on smoking cessation and other forms of treatment should be part of the routine care for diabetic smokers. However, both documents only include generic advice, rather than specific recommendations for intervention.

As noted, there is only limited information about specific recommendations regarding the best management approach to help diabetic patients to stop smoking. The approach is therefore the same as for patients with other chronic diseases, and is based on three essential principles: patient motivation, cognitive behavioral therapy, and drug treatment. These interventions must be at least as intensive as in the general population, with cognitive behavioral therapy and drug treatment being adapted to the characteristics of the disease and the patient.

A significant proportion of Spanish departments of endocrinology and nutrition have educational units that may help diabetic patients in matters such as diet control, symptom management, and training on insulin self-administration. These units have made a significant contribution to the management of those patients. However, despite their excellent potential for motivating, advising, and recommending smoking cessation, there is a lack of homogeneity in the specific anti-smoking interventions carried out at such units. On the other hand, and despite all the above, some surveys have found that only 58% of all diabetic smokers report that they have been advised by their physician to quit smoking.44

Cognitive behavioral therapyMotivation is a key element in the decision to stop smoking. In patients with established disease–diabetes in this case–, motivation should be based on written and verbal information on the impact of smoking upon the course of the disease, with the benefits of smoking cessation being emphasized.

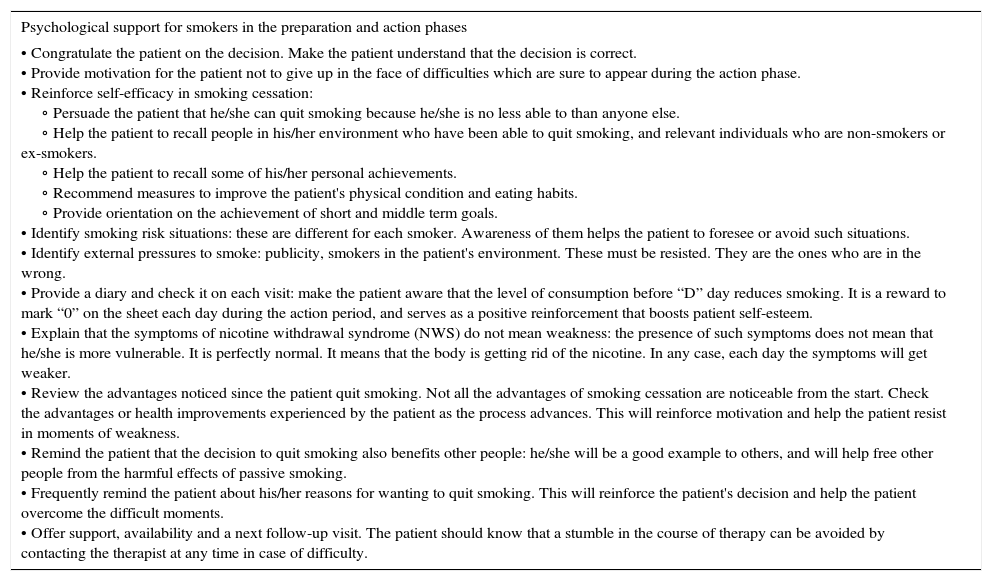

Behavioral intervention in diabetic patients should be adapted to the characteristics of the patient and the means available, and ranges from anti-tobacco health counseling to more intensive interventions. Counseling should be motivating, vigorous but friendly, brief (no more than 3min), and systematic, i.e. should be repeated at all patient visits. More intensive approaches combine cognitive interventions designed to inform patients about the benefits of smoking cessation, and behavioral plans including specific action schemes intended to disrupt the ties to smoking and to help the patient learn to live without the habit. Interventions of this kind should include a supply of written material and a diary for the patient to record the actual consumption and the specific circumstances in which each cigarette was smoked, with the purpose of achieving “deautomatization” and awareness of tobacco consumption. Table 1 summarizes the main psychological support activities that healthcare professional can apply to patients who smoke.

Main psychological support measures for smokers in the preparation and action phases.

| Psychological support for smokers in the preparation and action phases |

|---|

| • Congratulate the patient on the decision. Make the patient understand that the decision is correct. • Provide motivation for the patient not to give up in the face of difficulties which are sure to appear during the action phase. • Reinforce self-efficacy in smoking cessation: ∘ Persuade the patient that he/she can quit smoking because he/she is no less able to than anyone else. ∘ Help the patient to recall people in his/her environment who have been able to quit smoking, and relevant individuals who are non-smokers or ex-smokers. ∘ Help the patient to recall some of his/her personal achievements. ∘ Recommend measures to improve the patient's physical condition and eating habits. ∘ Provide orientation on the achievement of short and middle term goals. • Identify smoking risk situations: these are different for each smoker. Awareness of them helps the patient to foresee or avoid such situations. • Identify external pressures to smoke: publicity, smokers in the patient's environment. These must be resisted. They are the ones who are in the wrong. • Provide a diary and check it on each visit: make the patient aware that the level of consumption before “D” day reduces smoking. It is a reward to mark “0” on the sheet each day during the action period, and serves as a positive reinforcement that boosts patient self-esteem. • Explain that the symptoms of nicotine withdrawal syndrome (NWS) do not mean weakness: the presence of such symptoms does not mean that he/she is more vulnerable. It is perfectly normal. It means that the body is getting rid of the nicotine. In any case, each day the symptoms will get weaker. • Review the advantages noticed since the patient quit smoking. Not all the advantages of smoking cessation are noticeable from the start. Check the advantages or health improvements experienced by the patient as the process advances. This will reinforce motivation and help the patient resist in moments of weakness. • Remind the patient that the decision to quit smoking also benefits other people: he/she will be a good example to others, and will help free other people from the harmful effects of passive smoking. • Frequently remind the patient about his/her reasons for wanting to quit smoking. This will reinforce the patient's decision and help the patient overcome the difficult moments. • Offer support, availability and a next follow-up visit. The patient should know that a stumble in the course of therapy can be avoided by contacting the therapist at any time in case of difficulty. |

Source: The study authors.

The levels of evidence recommend advising all patients to quit smoking, with the inclusion of smoking cessation advice and other forms of treatment as added elements in routine diabetes care. Coordinated action by the specialist and primary care physicians allows for improved results.

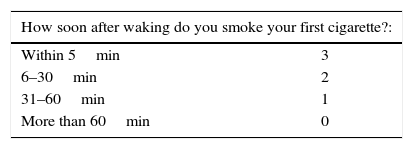

Drug treatmentDrug treatment should be provided along with psychological management in patients with a moderate or high physical dependence on nicotine as determined by the Fagerström test, shown in Table 2.

Modified Fagerström test. The test defines three degrees of dependence, with the indication of drug treatment in patients with moderate and high dependence.

| How soon after waking do you smoke your first cigarette?: | |

|---|---|

| Within 5min | 3 |

| 6–30min | 2 |

| 31–60min | 1 |

| More than 60min | 0 |

| Do you find it difficult to refrain from smoking in places where it is forbidden (e.g., hospitals, cinemas, libraries)?: | |

|---|---|

| Yes | 1 |

| No | 0 |

| Which cigarette do you need most?: | |

|---|---|

| The first one in the morning | 1 |

| Any other | 0 |

| How many cigarettes a day do you smoke?: | |

|---|---|

| Less than 10 | 0 |

| 11–20 | 1 |

| 21–30 | 2 |

| 31 or more | 3 |

| Do you smoke more frequently in the first hours after getting up than during the rest of the day?: | |

|---|---|

| Yes | 1 |

| No | 0 |

| Total score |

|---|

| 0–3: low dependence |

| 4–6: moderate dependence |

| 7–10: strong dependence |

Source: SEPAR guidelines. Smoking cessation therapy in smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The aim of drug treatment is to relieve the symptoms of nicotine withdrawal syndrome, the main cause of relapse in the first few weeks of treatment. In diabetic smokers, the specific considerations referred to in each of the available treatments described below should be taken into account.

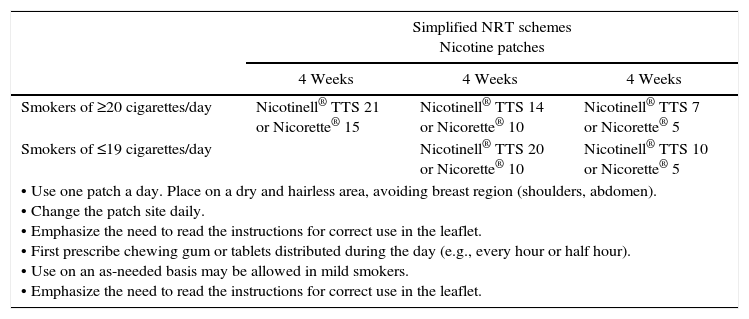

Nicotine replacement therapyNicotine replacement therapy (NRT) involves the administration of nicotine through a route other than cigarette smoking and in amounts sufficient to reduce or avoid withdrawal syndrome, but insufficient to maintain dependence. Regardless of the form used, it is administered in decreasing (i.e., tapered) doses. In Spain, nicotine is available in the form of chewing gum, tablets, oral sprays, and transdermal patches. The different formulations may be used alone or in combination, with patches being used as background therapy and tablets, chewing gum, or oral spray used as needed. The accepted indications include smoking cessation as adjuvant treatment, a progressive reduction of the number of cigarettes, and temporary abstinence (hospital stays, long distance flights, etc.). The main dosage schemes are shown in Table 3.

Dosage schemes of the different presentations of NRT and NRT contraindications.

| Simplified NRT schemes Nicotine patches | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 Weeks | 4 Weeks | 4 Weeks | |

| Smokers of ≥20 cigarettes/day | Nicotinell® TTS 21 or Nicorette® 15 | Nicotinell® TTS 14 or Nicorette® 10 | Nicotinell® TTS 7 or Nicorette® 5 |

| Smokers of ≤19 cigarettes/day | Nicotinell® TTS 20 or Nicorette® 10 | Nicotinell® TTS 10 or Nicorette® 5 | |

| • Use one patch a day. Place on a dry and hairless area, avoiding breast region (shoulders, abdomen). • Change the patch site daily. • Emphasize the need to read the instructions for correct use in the leaflet. • First prescribe chewing gum or tablets distributed during the day (e.g., every hour or half hour). • Use on an as-needed basis may be allowed in mild smokers. • Emphasize the need to read the instructions for correct use in the leaflet. | |||

| Simplified NRT schemes Chewing gum 2mg or tablets 1mg | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smokers of 10–20 cigarettes/day | ||||||||||||

| Week | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| No. pieces/day | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Smokers of 20–40 cigarettes/day | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| No. pieces/day | 24 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 16 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| Contraindications of NRT | |

|---|---|

| Generally applicable to all forms of NRT | Recent (8 weeks) acute myocardial infarction, angina or unstable heart disease and severe cardiac arrhythmias Pregnancy and lactation Active gastroduodenal ulcer Severe mental disease Low motivation |

| Specific to chewing gum and tablets | Dental problems Temporomandibular joint disorders (only chewing gum) Oropharyngeal inflammation (oral thrush, glossitis, etc.) |

| Specific to patches | Eczema, atopic dermatitis or generalized skin diseases |

Source: The study authors.

Nicotine replacement therapy is considered the option of choice in diabetic smokers, though it should be taken into account that nicotine patches may cause a vasoconstriction similar to that produced by smoking, thus impairing insulin absorption. Close monitoring of blood glucose levels is therefore required, and a temporary adjustment of insulin or oral antidiabetic doses may sometimes be needed. This circumstance should also be taken into account if the patient has serious vascular problems derived from diabetes.3

NRT is safe and well tolerated, with few adverse effects that only rarely require its discontinuation or a treatment switch. The main contraindications to NRT, described in Table 3, are related to the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular effects of nicotine.

BupropionBupropion was the first oral non-nicotine treatment approved for smoking cessation in the United States in 1997. It is a monocyclic antidepressant that inhibits norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake at neuronal synapses in the central nervous system, behaving as a non-competitive antagonist of nicotine receptors.7 Bupropion is safe for diabetic patients, and adequate for use as a first-line drug treatment. Whenever possible, bupropion should be used together with psychological support or behavioral therapy, since the combined use of drug and non-drug strategies increases the chances of treatment success.

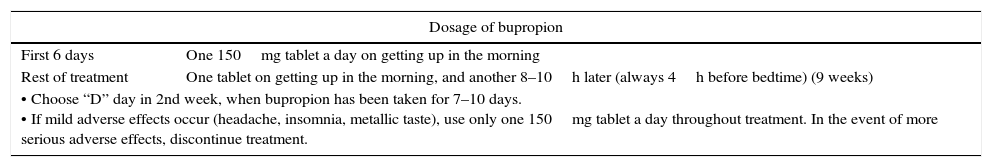

Bupropion may lower the seizure threshold, and susceptible patients or individuals with known risk factors for seizures therefore require close monitoring. Potential drug interactions should also be monitored. Although no studies are available in diabetic patients, the recommendation is 150mg/day in a single morning dose. Table 4 shows the usual dosage scheme and the main contraindications and drug interactions of bupropion.

Dosage schemes, contraindications, and interactions of bupropion.

| Dosage of bupropion | |

|---|---|

| First 6 days | One 150mg tablet a day on getting up in the morning |

| Rest of treatment | One tablet on getting up in the morning, and another 8–10h later (always 4h before bedtime) (9 weeks) |

| • Choose “D” day in 2nd week, when bupropion has been taken for 7–10 days. • If mild adverse effects occur (headache, insomnia, metallic taste), use only one 150mg tablet a day throughout treatment. In the event of more serious adverse effects, discontinue treatment. | |

| Contraindications and interactions of bupropion | |

|---|---|

| Contraindications | • Seizures or a history of seizures • Bulimia or anorexia nervosa • Liver cirrhosis • Bipolar disorder • Concomitant use of MAOIs • CNS tumors • Patients undergoing alcohol detoxification or benzodiazepine withdrawal Pregnancy and lactation |

| Interactions | • Lower the efficacy of bupropion: carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin • Increase the toxicity of bupropion: cimetidine, valproic acid, fluoxetine, ritonavir, MAOIs • Bupropion increases the toxicity of: levodopa, zolpidem, antidepressants, antipsychotics, beta-blockers, flecainide, mexiletine. • Seizure threshold is lowered bya: a history of severe head trauma, alcoholism, opiates, cocaine and stimulants, insulin, oral antidiabetics, antipsychotics, antidepressants, theophylline, quinolones, corticosteroids, antimalarials, tramadol, antihistamines with sedative action |

To sum up, the use of bupropion in diabetic smokers is not contraindicated, but the drug should be used with caution, at a dose of 150mg/day, along with a close monitoring of blood glucose levels and antidiabetic treatment adjustments if needed. A number of studies consider bupropion to be the drug treatment for smoking cessation that results in the lowest weight increase, and could therefore be the treatment of choice in obese diabetics (either alone or combined with NRT), provided the abovementioned precautions are observed.11,12

VareniclineVarenicline is the latest treatment approved for smoking cessation, and is the first drug specifically developed for this purpose. Varenicline is a selective partial agonist of the α-4 and β-2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which determine the release of various neurotransmitters, particularly dopamine, thereby simulating the usual effects of nicotine-induced dopamine release. Since varenicline is a partial agonist, it has an antagonistic effect upon the nicotine reward mechanisms, and is therefore particularly useful in preventing relapse.

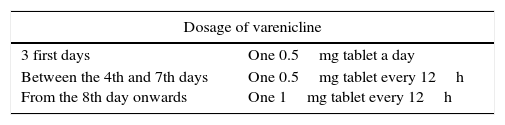

The drug is effective and safe for smokers who wish to quit smoking. No specific studies in diabetic patients are available, and there is therefore no scientific information limiting or contraindicating the use of varenicline in diabetic smokers. However, in patients with diabetic neuropathy or renal failure (creatinine clearance <30mL/min), the dose should be halved and administered with caution, with frequent controls. In any case, and as with any other drug treatment, the monitoring of blood glucose levels is advisable at the start of treatment. Table 5 shows the dosage scheme and the main contraindications and interactions of varenicline.

Dosage, contraindications, and adverse effects of varenicline.

| Dosage of varenicline | |

|---|---|

| 3 first days | One 0.5mg tablet a day |

| Between the 4th and 7th days From the 8th day onwards | One 0.5mg tablet every 12h One 1mg tablet every 12h |

| Contraindications and adverse effects of varenicline | |

|---|---|

| Contraindications | • Alcohol or other types of drug dependence • Pregnancy • Renal failure less than grade 3 (creatinine clearance <30mL/min); consider alternative treatment |

| Adverse effects | • Sleep disturbances (insomnia, nightmares) • Headache • Gastrointestinala - Flatulence - Dyspepsia - Constipation - Altered taste perception • Neuropsychiatricb - Mood changes - Anxiety - Depressive symptoms - Suicide ideation |

The EAGLES study, published in June 2016,45 assessed the neuropsychiatric safety of NRT, bupropion, and varenicline, as there has been some controversy in this regard since these drugs were launched. The study included more than 8000 patients and concluded that there were no increased neuropsychiatric side effects with any of the drugs. Varenicline was found to be the most effective drug, and both bupropion and NRT were seen to be more effective than placebo.

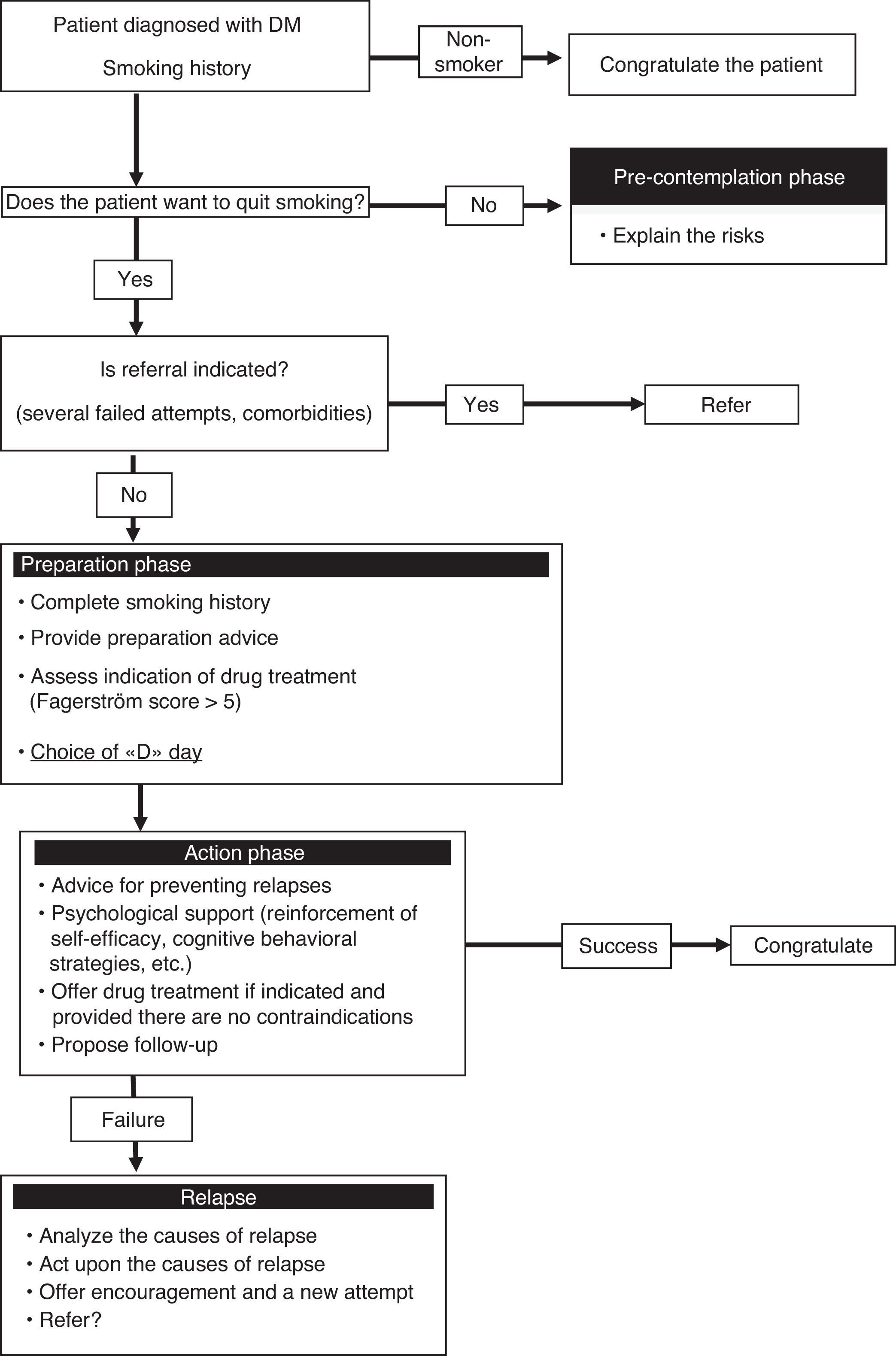

Experience of a smoking cessation unitAt our hospital, diabetic smokers are usually referred from the department of endocrinology for both a first smoking cessation attempt and when previous attempts have failed. These patients are usually motivated but are also concerned about the way in which smoking may affect their diabetes control. As a result, both the disease itself, and the advice of the endocrinologist, are key elements in motivating the patient to stop smoking. At our unit, the smoking cessation success rate among diabetic patients is similar to that in all other smokers, though the fact that it is a specialized unit means that the results may be biased and cannot therefore be extrapolated to other settings such as nursing or primary care. Fig. 1 shows the smoking cessation management algorithm applied to diabetic patients in our unit.

ConclusionsSmoking is a risk factor for the development of diabetes and its cardiovascular complications. Diabetic smokers may find it harder to quit smoking due to the existence of still little known interrelations between insulin and dopaminergic mediators of the reward circuits. It is therefore essential to include smoking cessation motivation and the multicomponent management of dependence among the usual diabetes prevention and treatment measures, in both the primary and specialized care settings.

It is advisable that diabetes education programs include recommendations, advice and treatment which refer to nicotine dependence, in order to promote smoking cessation among diabetic smokers. A number of smoking cessation therapies are available, and all of them may be used in these patients, though the choice of drug treatment should be individualized and based on the characteristics, comorbidities, previous treatment, and preferences of the patient. A number of studies have examined the factors related to smoking initiation, cessation and relapse, but far more research is needed in the diabetic population.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: López Zubizarreta M, Hernández Mezquita MÁ, Miralles García JM, Barrueco Ferrero M. Tabaco y diabetes: relevancia clínica y abordaje de la deshabituación tabáquica en pacientes con diabetes. Endocrinol Nutr. 2017;64:221–231.