Familial Hypercholesterolemia is the most frequent genetic cause of premature coronary heart disease. The delay in the diagnosis prevents the correct early treatment. There are no effective screening strategies at the national level that ensure a correct diagnosis.

ObjectiveTo determine the capacity of a centralized laboratory for the diagnosis of Familial Hypercholesterolemia through the creation of a health program for population screening in the province of Huelva.

MethodActive search of patients with primary hypercholesterolemia through the blood tests carried out in the reference laboratories with results of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol greater than 200 mg/dl and assessment in the Lipid Unit of Huelva to identify index cases, with subsequent family cascade screening.

Results37,440 laboratory tests with lipid profile were examined. After screening, 846 individuals were seen in the Lipid Unit, of which they were diagnosed according to criteria of the Dutch Lipid Clinic Network as possible 654 and probable/definitive 192 individuals, representing 1.74% and 0.51% of the general population examined respectively.

ConclusionsThe point prevalence of Familial Hypercholesterolemia in patients submitted to laboratory lipid profile tests was 1:195, higher compared to the prevalence of Familial Hypercholesterolemia in the general population (based on 1 in 200–300). The opportunistic search strategy of the index case through a laboratory alert and centralized screening is an efficient strategy to implement a national screening for the diagnosis of Familial Hypercholesterolemia.

La hipercolesterolemia familiar es la causa genética más frecuente de enfermedad coronaria prematura. El retraso en el diagnóstico impide el correcto tratamiento precoz. No existen estrategias efectivas de cribado a nivel nacional que aseguren un correcto diagnóstico.

ObjetivoDeterminar la capacidad de un laboratorio centralizado para el diagnóstico de hipercolesterolemia familiar mediante la creación de un programa de salud para el cribado poblacional en la provincia de Huelva.

MétodoBúsqueda activa de pacientes con hipercolesterolemia primaria a través de las analíticas realizadas en los laboratorios de referencia con resultados de colesterol unido a lipoproteínas de baja densidad mayor de 200 mg/dl y valoración en la Unidad de Lípidos de Huelva para identificar casos índice, con realización posterior de diagnóstico en cascada familiar.

ResultadosSe examinaron 37.440 analíticas con perfil lipídico. Tras el cribado fueron vistos en la Unidad de Lípidos 846 individuos, de los cuales fueron diagnosticados según criterios de la Red de Clínicas de Lípidos Holandesas como posibles 654 y probables/definitivos 192 individuos, lo que supone el 1,74% y el 0,51% de la población general examinada, respectivamente.

ConclusionesLa prevalencia puntual de hipercolesterolemia familiar en pacientes sometidos a pruebas de perfil lipídico de laboratorio fue de 1:195, mayor en comparación con la prevalencia de hipercolesterolemia familiar en la población general (basado en 1 de cada 200–300). La estrategia de búsqueda oportunista del caso índice a través de una alerta de laboratorio y cribado centralizado es una estrategia eficiente para implantar un cribado nacional para el diagnóstico de hipercolesterolemia familiar.

Familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) is a genetic disease caused by mutations in the genes involved in cholesterol metabolism, mainly in the low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) gene (90%), and to a lesser extent in apolipoprotein B100 (APOB) genes (5%) and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) (1%).1,2 The prevalence of heterozygous FH (HeFH) has been estimated at 1 in 250–500 individuals, with a recent meta-analysis estimating the prevalence at 1 in 311, affecting 25 million people worldwide world.3

It is the most common monogenic disorder in premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). These patients have an average risk 3–13 times higher for ASCVD than the general population,4 and life expectancy can be shortened by 20–30 years compared to unaffected subjects, due to the fact that exposure to high cholesterol bound to low-density lipoproteins (LDL-C) from birth accelerates coronary atherosclerosis by one to four decades.5–8 Treatment with diet, exercise and statins improves the prognosis of patients with FH, thereby reducing the risk of premature ASCVD tenfold. Early detection of FH is therefore essential.

Most patients with FH are still at the level of primary healthcare, in general undiagnosed and therefore with no or insufficient treatment. The most widespread action to date is opportunistic screening in primary care among patients with primary hypercholesterolaemia and a personal/family history of premature cardiovascular disease, while at a hospital level, they look for index cases (ICs) among patients with premature cardiovascular disease and hypercholesterolaemia.6 However, this is insufficient for identifying the majority of cases of FH. It is currently estimated that nine out of 10 individuals born in the world with FH remain undiagnosed.9,10

In some countries, they have studied adding alert systems to laboratory analysis of cholesterol levels as a strategy to establish a likely diagnosis of FH.11 In order to use these alert systems as screening, secondary causes also need to be ruled out and a clinical assessment is necessary to make the phenotypic diagnosis of FH. One of the problems, however, is the poor awareness of the disease. There are no published studies of this type in Spain.

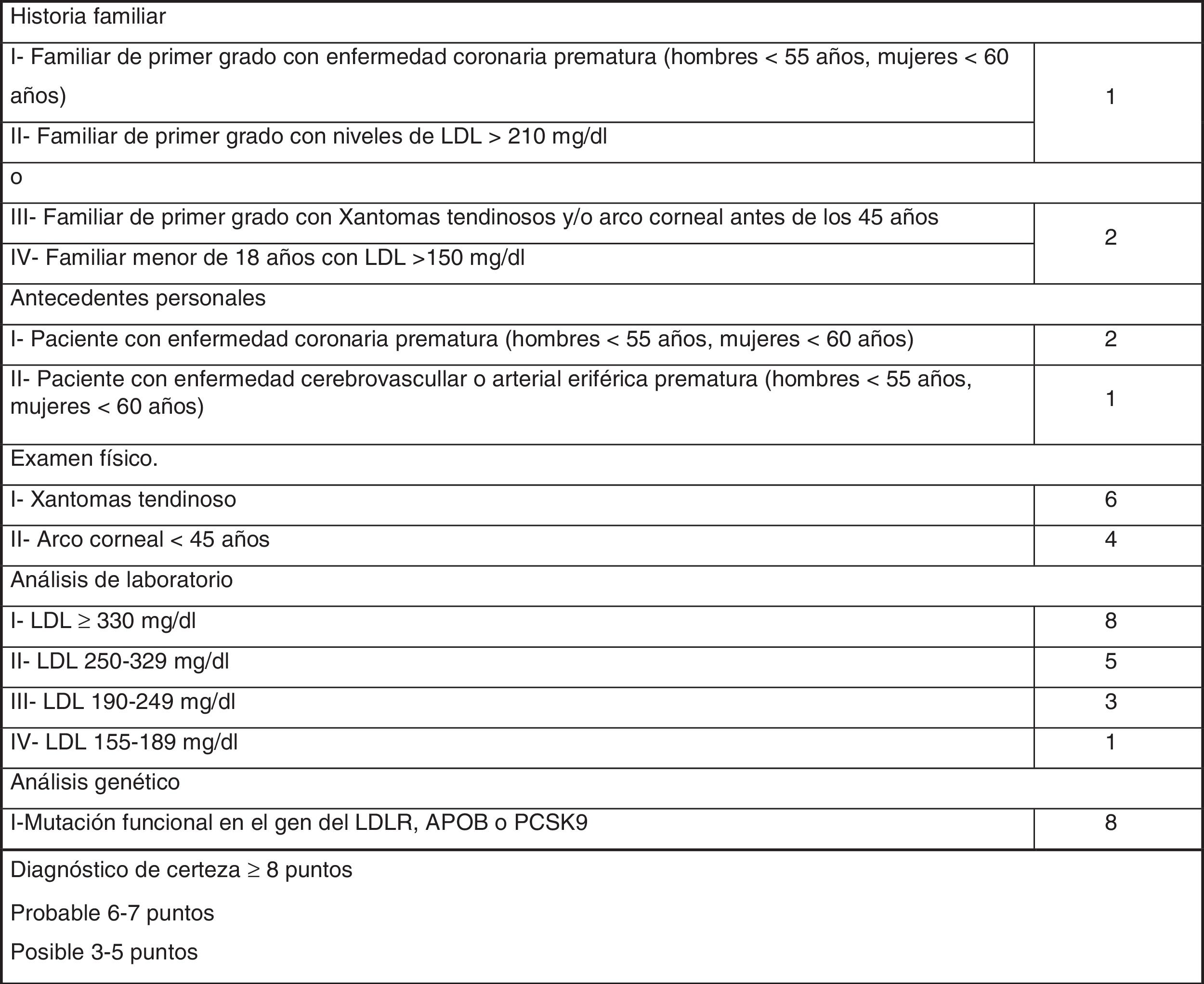

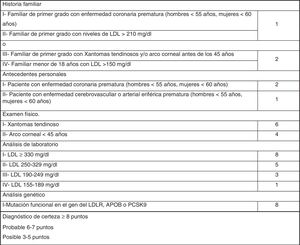

The most widely used phenotypic diagnostic criteria for FH are those of the Dutch Lipid Clinic Network (DLCN), for use in adults >18 years of age (Fig. 1). Based on LDL-C levels, clinical examination, family history and genetic testing, the chances of having FH are determined using the DLCN criteria: definite FH, score of 8 or above; probable FH, score of 6–7; possible FH, score 3–5; and score below 3, FH unlikely.12

If we combine active searching for ICs through the centralised clinical analysis laboratory with assessment of suspected cases from medical records, we may be able to achieve more extensive diagnosis. The DETECTA HF HUELVA [HUELVA DETECT FH] programme was set up for this purpose. There have been cases in which a probable phenotypic diagnosis was reached, starting from the LDL-C level and after ruling out secondary causes.13

The aim of this programme was to study the potential viability of a hospital laboratory as a tool for the opportunistic detection of ICs, with the support of the Lipids Unit to establish the diagnosis of FH.

Material and methodStudy populationThe population of Huelva (in the south-west of Spain) is 519,932 people. All lipid profiles performed in the province’s reference laboratories from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2018 were reviewed and all patients with LDL-C results above 200 mg/dl were selected.

Exclusion criteria were: the patient had died; the patient did not belong to our health area; being under the age of 18; having terminal cancer; having advanced cognitive impairment; having insufficient data for a complete assessment; having high cholesterol in isolation; and having triglyceride levels above 200 mg/dl.

After identifying these patients, we analysed the data to rule out those who had clinical or laboratory data compatible with secondary hypercholesterolaemia (nephrotic syndrome, uncontrolled thyroid disease, cholestasis and pregnancy).

Assessment in the programmeBefore starting, the programme was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (Reference 0570-N-17). The selected patients with primary hypercholesterolaemia were assessed at the first visit by the programme nurse, who completed a questionnaire and carried out a general physical examination, which included assessment for xanthoma and corneal arcus, family history of hypercholesterolaemia and early cardiovascular disease, and the traditional cardiovascular risk factors. All patients who wished to take part in the programme signed an informed consent form and had a blood test with lipid profile biochemistry analysis.

The DLCN criteria were applied to all these patients. Genetic testing for FH was organised for those with a DLCN score ≥6. The genetic testing included the sequencing of the LDLR, APOB, PCSK9, APOE and STAP1 genes in the GENinCode genetics laboratory. Subsequently, and with the collaboration of the Fundación de Hipercolesterolemia Familiar [Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Foundation], familial cascade genetic testing was carried out during the First Conference on Familial Hypercholesterolaemia in Huelva.

Statistical analysisQualitative data are expressed as percentages and quantitative data as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Confidence intervals (CI) were calculated at 95%. The Chi-square test was used to compare proportions. Student’s t test was used to compare means. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

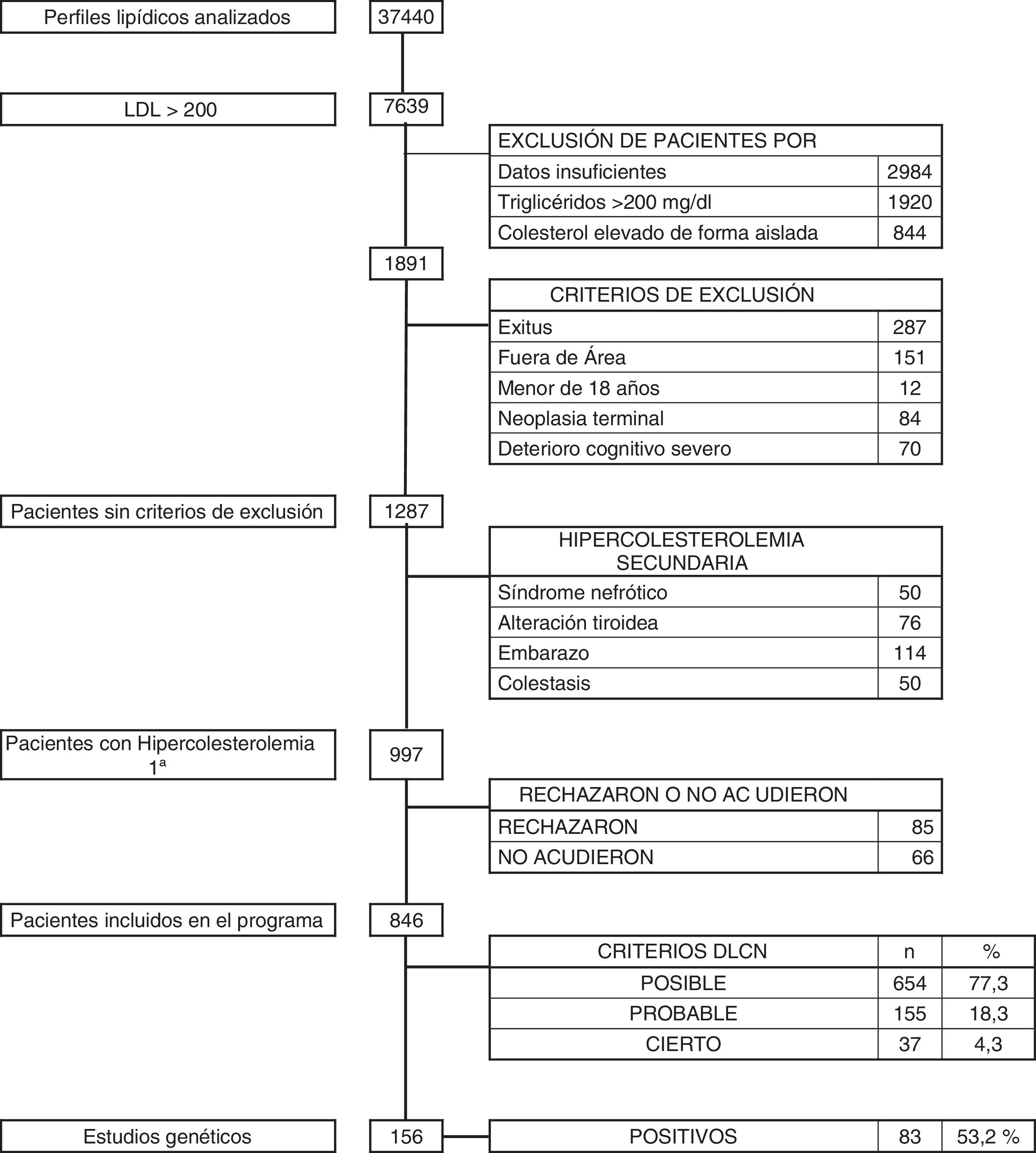

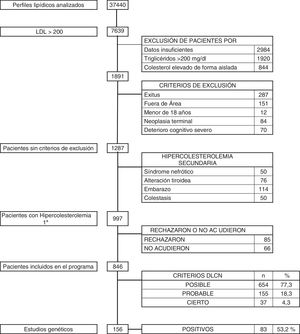

ResultsOver the 36-month period, a total of 37,440 blood tests with lipid profile were reviewed. There were 1891 subjects with LDL-C above 200 mg/dl. Patients who met any of the exclusion criteria were discounted: 287 who had died; 151 who did not belong to our health area; 12 aged under 18; 84 with terminal cancer; and 70 with advanced cognitive impairment. After the above screening, with 1287 patients remaining, a further 290 (0.77%) were excluded for having secondary hypercholesterolaemia, due to nephrotic syndrome (50), pregnancy (114), uncontrolled thyroid disease (76) and cholestasis (50). The remaining 997 patients (2.66%) were diagnosed with primary hypercholesterolaemia, and they were all asked to take part in the DETECTA HF HUELVA health programme. Of these, 151 patients refused to take part or did not attend the appointment (Fig. 2).

Finally, 846 subjects (2.25% of the initial total studied) with LDL-C above 200 mg/dl were assessed in the clinic: 1.7% (654/37,440) had a DLCN score of 3–5 (possible FH); 0.41% (155/37,440) scored 6–7 (probable FH); and 0.10% (37/37,440) scored 8 or above (definite FH). The score prevalence of phenotypic FH based on DLCN criteria as probable/definite and with an LDL-C above 200 mg/dl was calculated to be 0.51% (1 in 195).

During the DETECTA programme, a total of 246 genetic tests were carried out, 147 (53.2%) of which were positive. Within the DETECTA programme, 156 genetic tests were carried out on possible ICs, resulting in 83 positives (53.2%). In the DLCN group with a score of 8 or above there were 37 patients; genetic testing was carried out on 33 (89.12%), with 24 testing positive, representing 72.7% of the tests carried out in this group. The DLCN 6–7 group consisted of 155 patients, and genetic testing was carried out on 103 (66.5%), with 51 testing positive (49.5%). In the DLCN 3–5 group, genetic testing was carried out on 20 individuals, eight of them being positive, reducing the proportion of positives to 40%. After the identification of ICs by genetic testing, the First Conference on Familial Hypercholesterolaemia was held. A total of 32 ICs were selected and cascade genetic testing was carried out on 90 individuals, with 62 of them (68.9%) testing positive.

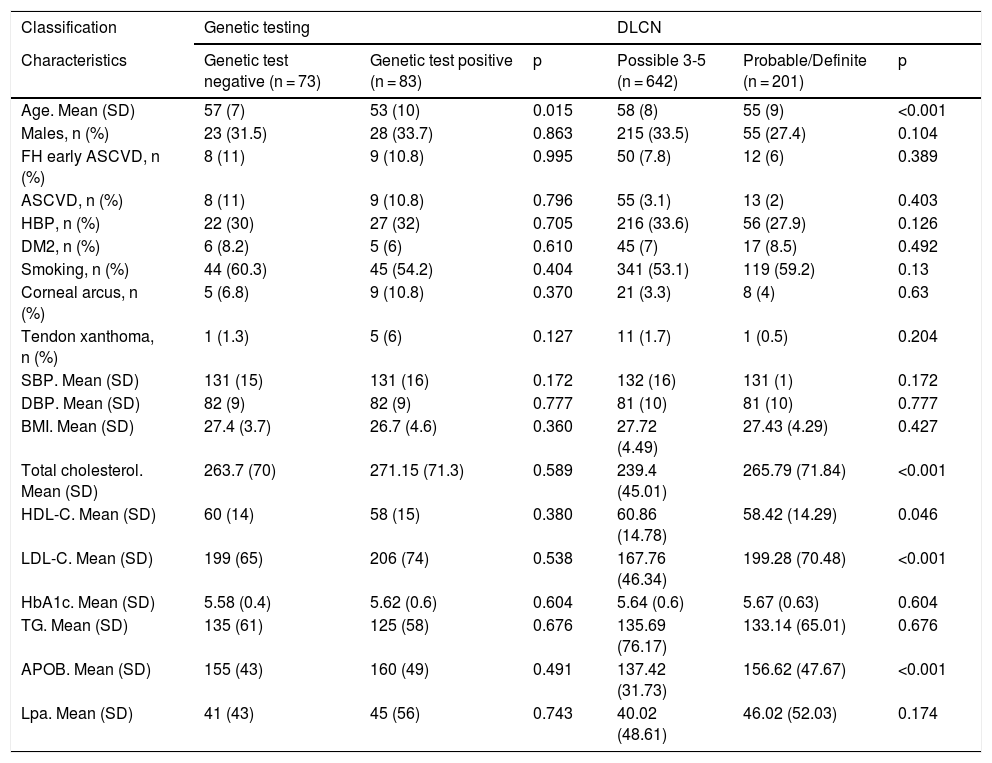

The characteristics of the patients with a genetic diagnosis are compared in Table 1. The mean age of the positive patients was 53 and 76% were female. Both groups were similar. We also compared the characteristics of patients diagnosed by DLCN criteria, finding a significant increase of approximately 30 mg/dl in the probable/definite FH group versus the possible FH group in cholesterol (239.4 vs 265.7), LDL-C (167.7 vs 199.2) and apolipoprotein B test (137.4 vs 156.6), respectively.

Characteristics of patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia participating in the DETECTA HF-HUELVA health programme. Comparison of patient characteristics according to genetic testing results and according to DLCN criteria.

| Classification | Genetic testing | DLCN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Genetic test negative (n = 73) | Genetic test positive (n = 83) | p | Possible 3-5 (n = 642) | Probable/Definite (n = 201) | p |

| Age. Mean (SD) | 57 (7) | 53 (10) | 0.015 | 58 (8) | 55 (9) | <0.001 |

| Males, n (%) | 23 (31.5) | 28 (33.7) | 0.863 | 215 (33.5) | 55 (27.4) | 0.104 |

| FH early ASCVD, n (%) | 8 (11) | 9 (10.8) | 0.995 | 50 (7.8) | 12 (6) | 0.389 |

| ASCVD, n (%) | 8 (11) | 9 (10.8) | 0.796 | 55 (3.1) | 13 (2) | 0.403 |

| HBP, n (%) | 22 (30) | 27 (32) | 0.705 | 216 (33.6) | 56 (27.9) | 0.126 |

| DM2, n (%) | 6 (8.2) | 5 (6) | 0.610 | 45 (7) | 17 (8.5) | 0.492 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 44 (60.3) | 45 (54.2) | 0.404 | 341 (53.1) | 119 (59.2) | 0.13 |

| Corneal arcus, n (%) | 5 (6.8) | 9 (10.8) | 0.370 | 21 (3.3) | 8 (4) | 0.63 |

| Tendon xanthoma, n (%) | 1 (1.3) | 5 (6) | 0.127 | 11 (1.7) | 1 (0.5) | 0.204 |

| SBP. Mean (SD) | 131 (15) | 131 (16) | 0.172 | 132 (16) | 131 (1) | 0.172 |

| DBP. Mean (SD) | 82 (9) | 82 (9) | 0.777 | 81 (10) | 81 (10) | 0.777 |

| BMI. Mean (SD) | 27.4 (3.7) | 26.7 (4.6) | 0.360 | 27.72 (4.49) | 27.43 (4.29) | 0.427 |

| Total cholesterol. Mean (SD) | 263.7 (70) | 271.15 (71.3) | 0.589 | 239.4 (45.01) | 265.79 (71.84) | <0.001 |

| HDL-C. Mean (SD) | 60 (14) | 58 (15) | 0.380 | 60.86 (14.78) | 58.42 (14.29) | 0.046 |

| LDL-C. Mean (SD) | 199 (65) | 206 (74) | 0.538 | 167.76 (46.34) | 199.28 (70.48) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c. Mean (SD) | 5.58 (0.4) | 5.62 (0.6) | 0.604 | 5.64 (0.6) | 5.67 (0.63) | 0.604 |

| TG. Mean (SD) | 135 (61) | 125 (58) | 0.676 | 135.69 (76.17) | 133.14 (65.01) | 0.676 |

| APOB. Mean (SD) | 155 (43) | 160 (49) | 0.491 | 137.42 (31.73) | 156.62 (47.67) | <0.001 |

| Lpa. Mean (SD) | 41 (43) | 45 (56) | 0.743 | 40.02 (48.61) | 46.02 (52.03) | 0.174 |

APOB: apolipoprotein B; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BMI: body mass index; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; DLCN: Dutch Lipid Clinic Network; DM2: type 2 diabetes mellitus; FH ASCVD: family history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin; HBP: high blood pressure (hypertension); LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lpa: lipoprotein a; SBP: systolic blood pressure; SD: standard deviation; TG: triglycerides.

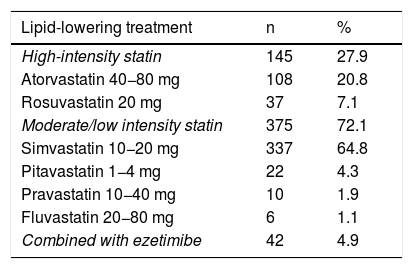

Only two patients with a probable diagnosis of FH and elevated LDL-C had a previous diagnosis of HeFH. Of the patients assessed in the clinic 38.5% were not on statin therapy. Of those who were receiving statin therapy, 72.1% were on low- or moderate-intensity statins and only 4.95% were on statin therapy plus ezetimibe (Table 2).

Lipid-lowering treatment received by patients on entering the health programme.

| Lipid-lowering treatment | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| High-intensity statin | 145 | 27.9 |

| Atorvastatin 40−80 mg | 108 | 20.8 |

| Rosuvastatin 20 mg | 37 | 7.1 |

| Moderate/low intensity statin | 375 | 72.1 |

| Simvastatin 10−20 mg | 337 | 64.8 |

| Pitavastatin 1−4 mg | 22 | 4.3 |

| Pravastatin 10−40 mg | 10 | 1.9 |

| Fluvastatin 20−80 mg | 6 | 1.1 |

| Combined with ezetimibe | 42 | 4.9 |

This study is the first to demonstrate high diagnostic performance with universal and sequential active screening of FH cases. Our study shows a high prevalence; at least 1 in 195 individuals in the patient cohort studied with severe hypercholesterolaemia (considered to be LDL-C >200 mg/dl), and a confirmation rate by genetic testing in the group with DLCN score ≥6 of 55.15%.

Our results are higher than the approximately 1:311 reported in the general population.3 However, the monogenic mutation responsible was not identified in all patients with a DLCN rating of probable or definite. The discrepancy between phenotypic and genotypic diagnoses may be explained by different factors: the existence of variants or mutations in genes not yet recognised as causing FH; the presence of mutations in regions not detected by the technology currently available, such as mutations mapped in deep intronic or distal promoter regions; the environmental effects on genes (epigenetic effects); or interactions between different genes in the same individual.14

Centralised laboratory assessment has several limitations, such as suboptimal documentation of medical records, which leads to underdiagnosis of secondary hypercholesterolaemia. Therefore, as in our programme, in addition to a cut-off point for LDL-C, diagnosis of FH requires a filter that can screen for secondary hypercholesterolaemia, drug use and assessment of family and personal clinical history, thus enabling a more reliable phenotypic diagnosis.

Up to the time of writing, few people had been diagnosed with FH in our province and these patients had no appropriate follow-up or treatment. For this reason the Lipid Unit set up the DETECTA HF HUELVA Health Programme, with the objective of detecting ICs and subsequently performing family cascade testing. The sample of 37,440 individuals analysed represents only 7.2% of the population of Huelva. Laboratory detection using the LDL-C cut-off point seems reasonable. The main difference with other centralised programmes is in the coordination between the laboratory and the Lipid Unit for proper phenotypic FH classification.

The fact that the ICs detected had not previously been diagnosed and the vast majority were not therefore on any treatment shows that training is still required for healthcare personnel in terms of detecting FH. It also supports the creation of routine “alert systems” to notify the requesting physician of all LDL-C levels above 200 mg/dl, so as to ensure further testing for FH or referral to Lipid Units. Active detection through the Lipid Unit's FH detection programme allowed 11.6% of our estimated population to be diagnosed with HeFH within one year of using the strategy described.

Screening programmes are essential in diagnosing prevalent diseases whose correct diagnosis and treatment can change the course of the condition. FH meets the WHO criteria for universal screening.9 The screening programmes vary considerably from country to country, and very often the diagnosis of FH is made after the onset of cardiovascular disease. Some of these programmes are based on the identification of patients with FH from amongst those with a premature coronary event. The Dutch registries report a prevalence of cardiovascular disease of 11% at the time of FH diagnosis; in the United Kingdom, the rate is 27% in males and 18.7% in females; in Spain, in the SAFEHEART registry, it is 13%15,16; in Israel, it is 36%8; and in Lithuania, it is 15%.17 Other screening programmes analyse the population using only clinical criteria, which may be, depending on the country, the Make Early Diagnosis to Prevent Early Deaths (MED-PED), the DLCN or the Simon Broome criteria, and do not carry out genetic testing, but this is probably due to the fact that in many countries it is not financed by the healthcare system.8 In Spain, there is no effective screening programme at a national level, or established uniformly in all the autonomous regions. This is one of the main barriers to effective prevention of premature heart disease for these patients in this country. Cost-effectiveness studies support family cascade screening as a main diagnostic tool.18–20

Patient characteristics in our health programme cohort are similar to those in previous reports, although with one main difference in the prevalence of cardiovascular events at diagnosis, which, at 10.5% in our patients, is lower than the rates published by other authors. In Spain, approximately 15% of the population with FH has had an atherosclerotic cardiovascular event, with similar figures in other countries such as the United States, Denmark and the United Kingdom.7,21 The main reason for this low prevalence is attributable to the active search for asymptomatic patients. By identifying the patients early, we can ensure that they are fully assessed and receive appropriate treatment recommendations, to try to delay or even prevent these complications from developing. Early use of statins either with or without ezetimibe in FH has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality rates.22–24 The lack of a prior diagnosis of FH in our patients partially explains why less than 12% were being treated with high-intensity statins. Despite suitable therapy with statins and/or ezetimibe, some patients do not achieve the therapeutic goal. However, the introduction of new lipid-lowering treatments, such as the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, has been shown to enhance the decrease in LDL-C in these patients, helping them achieve the recommended targets.4,25–27

ConclusionsOur results show that the diagnostic strategy of a centralised laboratory alert system is effective. Doing an initial screening in the laboratory with alert sent to the doctor requesting the analysis, combined with opportunistic screening for suspected cases and subsequent referral to specialised clinics, could be an efficient national screening programme. FH awareness and training in the different medical areas and close collaboration with primary care physicians are essential for this screening programme to be effective.

AuthorshipConception and design of the study: Manuel Jesús Romero Jiménez. Data acquisition: María Angustias Díaz Santos. Data analysis and interpretation: María Elena Mansilla Rodríguez and Elena Sánchez Ruiz-Granados. Writing of the article: Eva Nadiejda Gutiérrez-Cortizo. Critical review of intellectual content: Manuel Jesús Romero-Jiménez, Francisco Javier Caballero Granados and José Luis Sánchez Ramos. Final approval of the version to be submitted: Eva Nadiejda Gutiérrez-Cortizo, Manuel Jesús Romero-Jiménez and Pedro Mata.

FundingTo carry out this health programme we received funding from the Fundación Andaluza Beturia para la Investigación en Salud (FABIS) [Andalusian Beturia Foundation for Health Research].

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Gutiérrez-Cortizo EN, Romero-Jiménez MJ, Rodríguez MEM, Santos MAD, Granado FJC, Ruiz-Granados ES, et al. Detección de hipercolesterolemia familiar a través de datos analíticos centralizados. Programa DETECTA HF HUELVA. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:450–457.