Our aim was to evaluate the efficacy and security of ultrasound-guided percutaneous ethanol injection therapy (US-PEIT) for the treatment of recurrent symptomatic thyroid cysts in two high-resolution consultations of thyroid nodule in the Valencian Community.

Patients and methodsThe study comprised thirty-three consecutive patients (51 ± 12 years, 76% women) with symptomatic benign thyroid cysts relapsed after drainage and benign cytology prior to treatment. Through ultrasound, maximum cyst diameter and volume were determined, and the content of the cyst was drained. We then instilled between 2 and 4 ml of ethanol (according to initial volume). We followed up with ultrasound at one, 3, 6 and 12 months and we calculated the total volume and the Volume Reduction Rate (VRR). We evaluated the perceived pain using a visual analog scale.

ResultsThe initial median cyst volume was 11.6 ml (8.5–16.5) A single session of US-PEIT was required in 22 patients (67%), two in 8 (24%) and three in 3 (9%). During PEIT, 49% of the patients experienced virtually no pain, 39% mild pain and 12% moderate pain. There were no complications. After 6 months of follow up the median VRR was 93% (84–98). All the patients achieved a volume reduction of more than 50%, 94% of more than 70% and 56% of more than 90%. Twenty-four patients completed a year of follow-up, achieving a VRR of 97% (93–98).

ConclusionsIn our experience US-PEIT has proven to be an effective, safe treatment of symptomatic thyroid cysts. For this reason it can be considered as the first line of treatment and included in the portfolio of services of a high-resolution consultation.

Nuestro objetivo es evaluar la eficacia y la seguridad del tratamiento mediante inyección percutánea de etanol guiada por ecografía (IPE-US) de los quistes tiroideos sintomáticos en 2 consultas de alta resolución (CAR) de nódulo tiroideo de la Comunidad Valenciana.

Pacientes y métodosIncluimos 33 pacientes (51 ± 12 años, 78% mujeres) con quistes tiroideos sintomáticos que recidivaron tras drenaje inicial, con citología benigna previa al procedimiento. Mediante ecografía medimos diámetros y volumen, aspiramos el contenido del quiste e instilamos entre 2 y 4 ml de etanol (según volumen quístico). Realizamos seguimiento ecográfico al mes, 3, 6 y 12 meses, calculamos el volumen total y la tasa de reducción del volumen (TRV). Evaluamos el dolor percibido mediante una escala analógica visual.

ResultadosLa mediana del volumen inicial fue 11,6 ml (8,5–16,5). Realizamos un único procedimiento de IPE-US en 22 casos (67%), 2 en 8 (24%) y 3 en 3 (9%). El 49% de los pacientes no experimentó dolor, dolor leve el 39% y moderado un 12%. No hubo ninguna otra complicación. A los 6 meses de seguimiento la mediana de la TRV fue del 93% (84–98). Se alcanzó una reducción superior al 50% en todos los casos, mayor al 70 en el 94% y mayor del 90 en el 56%. Completaron 12 meses de seguimiento 24 pacientes, siendo su TRV del 97% (93–98).

ConclusionesLa IPE-US es eficaz y segura en el tratamiento de quistes tiroideos sintomáticos, por lo que puede ser considerada como primera línea de tratamiento e incluirse en la cartera de servicios de una CAR de nódulo tiroideo.

The prevalence of palpable thyroid nodules in iodine-sufficient areas is 5% in females and 1% in males. However, the use of high-resolution ultrasound equipment makes it possible to detect thyroid nodules in 19%–68% of the population, most frequently in women and older people.1 Approximately 15%–25% of the nodules are predominantly cystic. Based on ultrasound criteria, we refer to pure cysts when the cystic content of the nodule is greater than 90%, and predominantly cystic when the cystic content is 50%–90%.2 Thyroid cysts are generally benign, but may require treatment due to compressive symptoms or aesthetic complaints. After percutaneous drainage, recurrence of the cyst occurs in over 80% of cases.3 Surgery has traditionally been the first-line treatment for recurrent thyroid cysts. However, the initial studies by Verde et al.4 and Zingrillo et al.5 showed ultrasound-guided percutaneous ethanol injection therapy (US-PEIT) to be an effective and safe alternative to surgical treatment. The injection of 96%–99% ethanol into the cyst cavity induces thrombosis of the small vessels and coagulative necrosis in the cyst wall, with interstitial oedema and granulomatous inflammation, followed by fibrosis, contraction and decrease in the volume of the lesion.5,6 US-PEIT is recommended in cystic lesions that occupy more than 60% of the total volume of the nodule, and is considered a therapeutic success when it achieves a volume reduction rate (VRR) greater than 50% of the initial volume of the cyst.6

In recent years, numerous groups have published their experience, with a success rate of 70%–100%, and a VRR of 70%–90%.7–11 The technique is also safe for patients, being well tolerated, causing little pain, generally no complications, and improving their quality of life.12,13 As a result, the latest updates of the main guidelines of scientific societies make US-PEIT the first line of treatment in recurrent thyroid cysts after initial drainage.1,2 However, few groups have reported their results after having introduced this technique in their clinical practice, primarily as an alternative to surgical treatment in patients with this disorder.1,14

The aim of our study was to analyse the outcomes of our experience with US-PEIT for recurrent symptomatic thyroid cysts in two one-stop clinics for thyroid nodules at two hospitals in the Spanish autonomous region of Valencia, in order to assess the inclusion of this procedure as first-line treatment in our portfolio of services.

Patients and methodsWe selected 33 consecutive patients treated for thyroid nodules in the one-stop clinics at Hospital General Universitario de Castellón and Hospital Universitario Doctor Peset in Valencia from October 2017 to June 2019. All patients had thyroid nodules of at least 5 ml in volume, with the cystic component greater than 80% of the total volume. The cysts recurred after at least one aspiration of contents, and patients complained of compressive symptoms or aesthetic problems. All the patients completed follow-up for at least six months.

To be included in the study, patients had to be over 18, with no major comorbidities, history of radiotherapy to the neck, treatment with radioactive iodine or previous surgery. In all cases, a medical history was taken, a physical examination was performed and blood samples were obtained for laboratory tests. All patients had normal levels of TSH and free thyroxine at baseline. They all received a detailed explanation of the procedure and signed an informed consent form. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital General Universitario de Castellón.

Thyroid ultrasoundThe ultrasound, the initial drainage and the US-PEIT were performed by an expert thyroid ultrasound technician at each hospital using a 12–15 MHz linear probe. Both technicians were accredited by the Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición (SEEN) [Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition] in ultrasound scanning of the neck and ultrasound techniques at intermediate level II.15 We assessed the morphology of the thyroid gland, including the echotexture and echogenicity, and we measured the diameters and assessed the ultrasound characteristics of each nodule detected. When thyroid nodules were detected, we performed fine needle aspiration (FNA) according to ACR TI-RADS 2017 criteria.16

Cyst volume was calculated using the ellipsoid model. We multiplied the three diameters (transverse, anterior/posterior and longitudinal) expressed in centimetres, and multiplied the result by the constant 0.524.17 We performed FNA of the capsule or solid part of the cyst, and another puncture to drain the contents. Drainage was performed with a 20 ml syringe with a 21 G needle. Cytology was benign in all cases.

Percutaneous ethanol injection procedureUS-PEIT was offered if the cyst showed significant growth after the first drainage or was causing compressive symptoms or aesthetic problems. Moreover, the patients preferred not to undergo surgery after the procedure was explained in detail. The procedure was similar to that described by Reverter et al.,12 but using a somewhat higher amount of ethanol, as advised by other authors.11,13 The amount of ethanol administered depended on the volume aspirated and was as follows: <10 ml: 2 ml ethanol; 10–14.9 ml: 2.5 ml ethanol; 15–19.9 ml: 3 ml ethanol; 20–30 ml: 3.5 ml ethanol; and >30 ml: 4 ml ethanol.

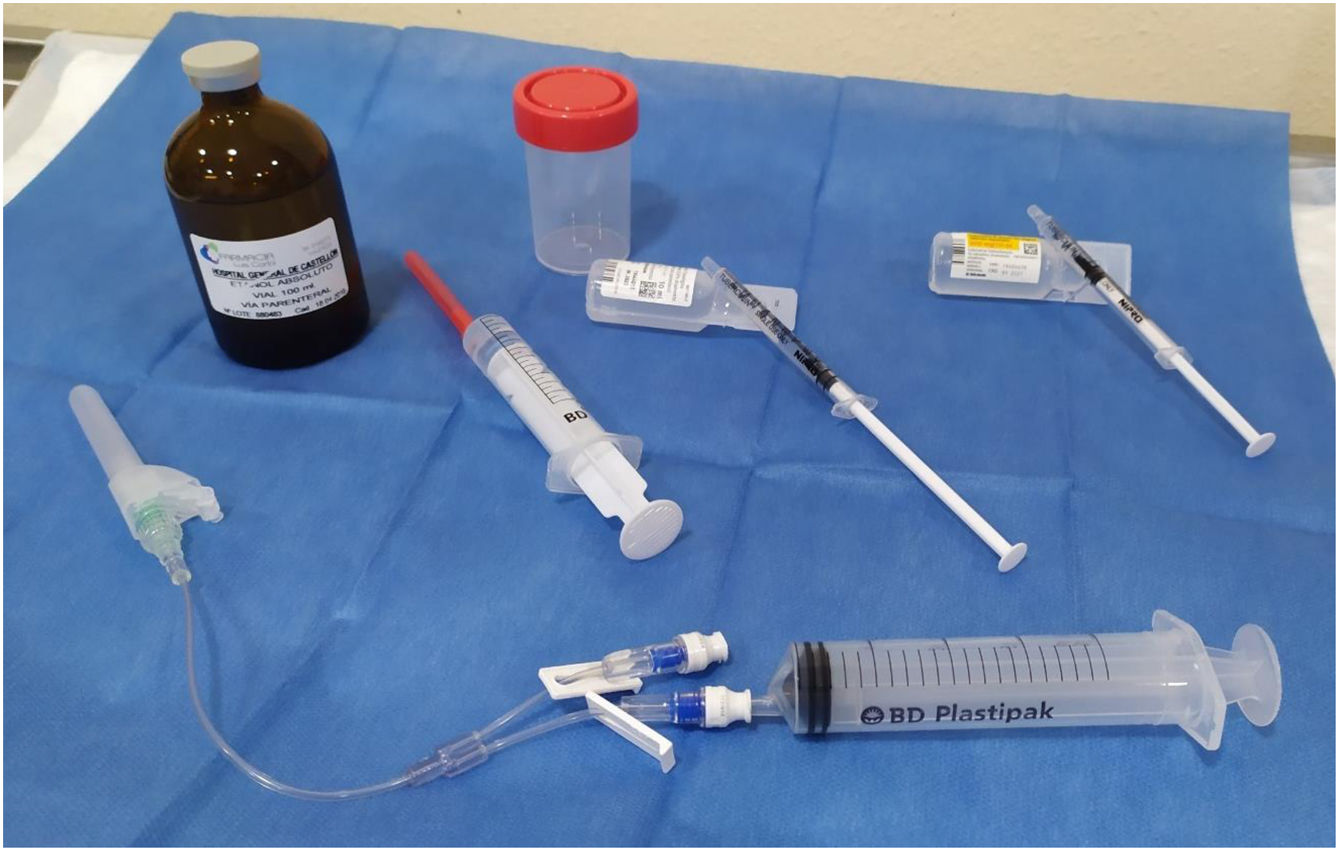

The materials used are shown in Fig. 1. The patients were put in the same position as for the FNA, lying on their back with their neck extended. After sterilising the skin, we used a 21 G needle mounted on an extension connector with 2 lumens, one connected to a 20 ml syringe to drain the cyst, and the other to administer lidocaine and ethanol. We drained the cyst, leaving a minimum amount of colloid in order to be able to see the tip of the needle properly and pointing the tip of the needle in the opposite direction to the location of the recurrent nerve. After removing the syringe, through the other lumen we administered 0.5 ml of 5% lidocaine. After two minutes, the syringe with lidocaine was replaced by another containing 96% ethanol, which was injected slowly, in small boluses of 0.5 ml. In a single application, 2–4 ml of ethanol was administered, approximately 15%–25% of the initial volume of the cyst (2, 2.5, 3, 3.5 or 4 ml, depending on whether the initial volume of the cyst was <10 ml, 10–14.9 ml, 15–19.9 ml, 20–30 ml or >30 ml, respectively). The tip of the needle remained visible throughout the procedure and in none of the cases was the ethanol introduced subsequently aspirated. The patient was instructed to indicate any type of pain they felt in order to avoid leaking of the alcohol into the structures of the neck. Additionally, to prevent the ethanol leaking out of the cyst, the needle was withdrawn during deep inspiration. All the patients remained under observation for 30 min before being discharged. Both technicians performed two procedures together, one at each site, to guarantee following the same protocol and using the same material in both hospitals.

Material used for drainage and percutaneous injection of ethanol. Bottom: 21 G syringe, double-lumen extension connector, one for drainage and one for injection. Middle, from left to right: a syringe with ethanol, a syringe with saline for wash-out and a syringe with 0.5 ml of 5% lidocaine. Top: absolute ethanol for parenteral use and sterile bottle for the drained cystic fluid.

At the follow-up visits, the reduction in cyst volume was estimated by the VRR using the following formula: {(Initial volume − Final volume)/Initial volume} × 100.9 The VRR was assessed by ultrasound at one, three and six months after the last US-PEIT. At 12 months, a final check-up was carried out to confirm the cyst had resolved. In the event of non-response, considered as volume reduction of less than 50% confirmed by ultrasound at the three- or six-month follow-up, we repeated the US-PEIT procedure, ensuring at least three months had elapsed since the previous procedure. Similarly, if at the three- or six-month follow-up, the volume was greater than 5 ml, or the symptoms persisted, a further US-PEIT was proposed even if the VRR was greater than 50%.

Pain assessmentThe patients were asked about the degree of pain experienced after the instillation of alcohol immediately after the completion of the procedure, using a 10-cm visual analogue scale (VAS), zero being considered as no pain and 10 as excruciating pain. Each patient was asked to indicate where the intensity of their pain was on this line. The distance to the patient’s numerical mark quantifies the intensity of their pain, the lower third being seen as mild pain, the middle third as moderate pain, and the upper third as severe pain.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis of the data was carried out with STATA v.14 software. Almost all the parameters analysed did not have a normal distribution according to the Shapiro–Wilk test. Therefore, the values were expressed as median and interquartile range (percentile: 25–75). We used the Mann–Whitney U test to compare the changes between the initial volume of the cyst and the VRR at one, three and six months after the US-PEIT. For correlation studies we used the Spearman correlation test. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant, and a Spearman correlation coefficient >0.25 to be a significant correlation.

ResultsWe performed initial drainage of 40 thyroid cysts, 33 (82%) of which recurred and were symptomatic, with a volume greater than 5 ml, and so these patients were included in the study protocol (six males and 27 females). The mean age was 51.1 ± 12.5 years. In all cases, thyroid hormones were normal and cytology benign. The median initial calculated cyst volume before the procedure was 11.6 ml (8.5–16.5) and the median maximum diameter was 3.5 cm (3.0–4.3). The aspirated volume was 9 ml (6–15) and the injected ethanol volume was 2.5 ml (2–3). The median number of US-PEIT procedures performed was one (1–2), (mean 1.4 ± 0.6 US-PEIT), with 22 patients requiring a single US-PEIT (67%), eight patients requiring two procedures (24%) and three patients requiring three procedures (9%). We did not carry out more than three US-PEITs in any of the cases. We found no differences in the initial volume of the cyst between the patients who underwent one US-PEIT and those who underwent two or three (11.7 [8.4–20.2] and 11.5 [8.8–15.8], respectively; NS). All the patients who required more than one US-PEIT presented a recurrence in the follow-up at one month.

The pain score during the US-PEIT procedure using a 10-cm VAS was 1 (1–3), (mean: 1.9 ± 1.4 cm); virtually absent in 16 cases (49%), mild in 13 (39%), and moderate in four (12%). None of the patients reported severe pain or other complications, and only two patients reported persistent pain following the US-PEIT and needed treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, although in neither case did the pain last beyond 24 h.

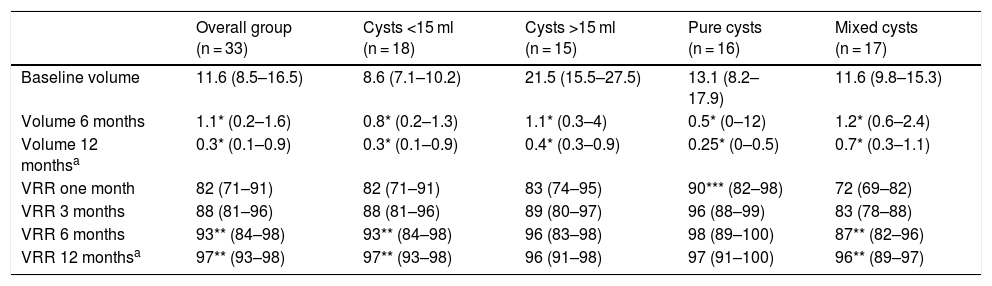

In all cases, US-PEIT was effective, achieving a reduction in cyst volume of more than 50%, and no recurrence during follow-up. At six months after the procedure, the volume of the cysts was 1.1 ml (0.2–1.6) and the largest diameter was 1.6 cm (0.6–2.1). The VRR was 82% (71–91) after one month, 88% (81–96) at three months and 93% (84–98) at six months, with the difference between the VRR at one and six months being statistically significant (p < 0.01) (Table 1). In all cases a VRR >50% was achieved: over 70% in 31 cases (94%); over 80% in 28 cases (82%); over 90% in 19 cases (56%); and complete disappearance in six cases (18%). The 12 months of follow-up were completed by 24 patients, with no significant changes compared to the six-month check-up (12-month volume: 0.3 ml [0.1–0.9]; 12-month VRR 97% [93–98]) and none of the cases was there an increase in size or reappearance of the cyst between six and 12 months.

US-PEIT results according to the characteristics of the nodule.

| Overall group (n = 33) | Cysts <15 ml (n = 18) | Cysts >15 ml (n = 15) | Pure cysts (n = 16) | Mixed cysts (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline volume | 11.6 (8.5–16.5) | 8.6 (7.1–10.2) | 21.5 (15.5–27.5) | 13.1 (8.2–17.9) | 11.6 (9.8–15.3) |

| Volume 6 months | 1.1* (0.2–1.6) | 0.8* (0.2–1.3) | 1.1* (0.3–4) | 0.5* (0–12) | 1.2* (0.6–2.4) |

| Volume 12 monthsa | 0.3* (0.1–0.9) | 0.3* (0.1–0.9) | 0.4* (0.3–0.9) | 0.25* (0–0.5) | 0.7* (0.3–1.1) |

| VRR one month | 82 (71–91) | 82 (71–91) | 83 (74–95) | 90*** (82–98) | 72 (69–82) |

| VRR 3 months | 88 (81–96) | 88 (81–96) | 89 (80–97) | 96 (88–99) | 83 (78–88) |

| VRR 6 months | 93** (84–98) | 93** (84–98) | 96 (83–98) | 98 (89–100) | 87** (82–96) |

| VRR 12 monthsa | 97** (93–98) | 97** (93–98) | 96 (91–98) | 97 (91–100) | 96** (89–97) |

US-PEIT: ultrasound-guided percutaneous ethanol injection therapy; VRR: volume reduction rate.

We assessed possible differences between the cysts depending on whether or not they were pure or mixed or their initial volume was greater or less than 15 ml (Table 1). With regard to type, 16 were pure cysts and 17 were mixed, predominantly cystic. We found no differences in any of the characteristics analysed except in the VRR after one month, which was higher in pure cysts than in mixed cysts (90% [82–98] vs 72% [69–82]; p < 0.01). Although the VRR was always higher in pure cysts compared to mixed cysts, after three months and beyond this difference was not statistically significant. We found no differences between pure and mixed cysts in the number of US-PEIT procedures required. The VRR between one and six months post-procedure was significantly higher in mixed cysts (72% [69–82] vs 87% [82–96]; p < 0.01), but not in pure cysts. We found no differences in the variables analysed between cysts smaller than 15 ml (n = 18) and larger than 15 ml (n = 15), except in the amount of ethanol administered, as this was determined by the volume of the cyst (2 ml [2.0–2.4] vs 3 ml [2.5–3.5]; p < 0.001). The initial response was slightly greater in cysts larger than 15 ml compared to smaller ones, although without reaching statistical significance. The VRR was, however, statistically significant between one and six months in cysts smaller than 15 ml (80% [71–86] at one month vs 93% [86–97] at six months; p < 0.01).

In the study of correlation, we found no association between the different variables.

DiscussionIn our experience, symptomatic benign thyroid cysts treated with US-PEIT after recurrence following initial drainage show a mean volume reduction of 89% at six months post treatment and 93% at 12 months, without developing complications. These outcomes confirm US-PEIT to be an effective, safe procedure, well tolerated by patients, which can be performed on an outpatient basis, and it should therefore be considered as first-line treatment as an alternative to surgery. Data published in the literature show that US-PEIT achieves a significant volume reduction, and even complete reabsorption, of thyroid cysts, with virtually no adverse effects.8,11,13 In fact, in their latest update, the American Thyroid Association guidelines and those of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and Assoziacione Medici Endocrinologi recommend US-PEIT as first-line treatment for cystic thyroid lesions.1–14

Drainage of thyroid cysts is an ineffective treatment as the recurrence rate is approximately 80%.7,18 In our experience, recurrence after initial drainage was 82%. US-PEIT, however, has been found to be superior to both single drainage (85.6% vs 7.3%)4,10 and saline injection (82% vs 48%).7

In large cohorts, such as that published by Lee and Ahn9 (n = 432), Halenka et al.11 (n = 200) and Negro et al.13 (n = 101), the VRR for cysts treated with US-PEIT ranged from 73% to 95%. Furthermore, US-PEIT is an effective long-term treatment. Raggiunti et al. found a 93% reduction in volume after seven years of follow-up.19 In our study, the VRR was 89% at six months and 93% at one year, in line with the rates reported in these large series, and also with the data published by Reverter et al. from a study of 30 patients carried out in Spain.12

There is no defined protocol for the US-PEIT procedure, and there is currently a degree of debate surrounding whether or not to aspirate the injected ethanol, the volume of ethanol administered, and whether or not to use local anaesthetic. In the early publications, the US-PEIT procedure was performed by injecting a relatively large volume of alcohol (50%–100% of the aspirated volume), with the alcohol reabsorbed after being left for a few minutes inside the cyst.4,6,10,18,20 However, in more recent reports, less alcohol is injected and the alcohol is not aspirated once injected. Kim et al. compared the aspiration of injected ethanol with no aspiration in 60 thyroid cysts.8 Although both approaches achieved similar results in terms of reducing the initial volume, aspiration required a mean procedure time 14 min longer than no aspiration and required a second puncture, leading to a greater risk of intra-cystic bleeding during the procedure (23% vs 3%). In recent years, practically all the published reports have carried out the US-PEIT with no aspiration of the injected ethanol.11–13

Greater debate surrounds the volume of ethanol injected per session. Reverter et al. report excellent results injecting a maximum of 2 ml of ethanol per session.12 Other groups also used a small but individualised volume of ethanol, between 15% and 25% of the initial volume of the cyst.11,13,19 We did not aspirate the injected ethanol and used a minimum volume of 2 ml for cysts of 5 ml and a maximum of 4 ml for cysts larger than 30 ml. In our opinion, these are still small volumes of ethanol, thus maintaining patient safety, but may allow for a reduction in the number of US-PEIT procedures. Administering 2 ml in all cases, Reverter et al. performed a single US-PEIT procedure in 45% of patients, two in 31% and three in 13%. They found an association between the initial volume and the number of procedures performed, with three or more being necessary if the cysts were larger than 30 ml.12 Negro et al. also administered a small volume of ethanol, but adjusted to the initial volume of the cyst, using a mean volume of 1.6, 2.8 and 3.4 ml according to cyst volume of less than 10 ml, 10–20 ml or 20–30 ml, only requiring one single US-PEIT in 86%, 56% and 61% of cases, respectively.13 In our study, with an approach very similar to that of Negro et al., 67% of the patients only required one US-PEIT procedure. We think that, in addition to the volume of ethanol administered, our good outcomes may be due to the fact that we did not include extremely large cysts (>100 ml) and only three were larger than 30 ml.

Although some studies conclude that the initial volume of the cyst is the only factor influencing VRR,10,12,18 other authors report better results in cysts smaller than 10 ml.6,7,20 There does seem to be a clear correlation between the initial volume of the cyst and the number of procedures required.12,19 Although the initial response in purely cystic nodules is greater than in mixed ones, there are no differences in VRR between the two in the medium and long term.9,21 It has been suggested that the solid part of the nodule could be more resistant to ethanol diffusion, which may explain this greater initial response of pure cysts immediately after US-PEIT. However, ethanol is gradually absorbed by the solid part of the nodule, and its sclerosing action persists over time, slowly and progressively reducing the size of nodules with a solid component.22 In addition to this, previous aspiration of the cyst fluid before the US-PEIT may also contribute to a greater initial reduction of pure cysts. We found no differences in the variables studied in the cysts according to initial size, but we did observe a faster reduction in volume initially in the pure cysts and in those larger than 15 ml, which disappeared in the medium to long term.

It has been suggested that the changes caused by ethanol in the thyroid tissue, such as necrosis and fibrosis, could cause complications if subsequent surgery of the gland is necessary.3 However, with US-PEIT, only the nodule is subjected to the ethanol action, with the extra-nodular thyroid tissue remaining unaffected, so it does not preclude subsequent surgical treatment, which can be performed safely.23

One of the priorities in all interventional procedures is patient safety. We specifically assessed pain using a visual analogue scale, and most patients reported no pain or minimal pain. Previous studies describe the presence of a transient burning sensation, slight in most cases, but of greater intensity in large cysts.7,24 This may be related to the high volume of ethanol injected, and not administering local anaesthesia. As in the Reverter et al. protocol,12 we instilled a small amount of lidocaine into the cavity just before administering the ethanol. We think that the lack of pain reported by most patients makes it advisable to include the administration of lidocaine in the procedure. However, this lengthens the procedure, and various authors report similar results in terms of pain without the use of lidocaine.11 Finally, a last aspect to be assessed is quality of life. Studies measuring quality of life show no differences in the general health status of patients compared to the general population, but they do show a significant improvement in symptoms related to the thyroid cyst.12,13

The main limitations of our study are the small number of cases (given that it is currently an effective and safe procedure), not having a control group and not having administered a quality-of-life questionnaire. The aim of the study was to determine the efficacy and safety of US-PEIT in order to assess adding the procedure to the department's portfolio of services, as it is the first-line treatment recommended by the main scientific societies. We consider that the number of cases treated and our experience may be useful for other one-stop clinics for thyroid nodules.

ConclusionsThe good outcomes in our clinical practice in the treatment of symptomatic thyroid cysts using US-PEIT and the safety provided to patients, with minimal perceived pain and the absence of complications, have led us to consider US-PEIT as the first-line treatment in our hospitals. The inclusion of this procedure in our centres will mean a significant reduction in the number of surgical interventions, hospital stays, patient discomfort, sick leave and possible complications. As this disease frequently affects young people, we believe that with the cyst confirmed as benign, US-PEIT should be offered as the treatment of choice to all patients with recurrence of the cyst after a first attempt at drainage. We recommend performing the procedure without aspirating the injected ethanol, administering small volumes of ethanol (between 2 and 4 ml depending on the initial volume of the cyst), and using lidocaine as an anaesthetic before instillation. We believe it is important to share results and unify the protocols for the procedure in different centres.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This work was possible thanks to the awarding of a grant for a Sonosite M-Turbo® ultrasound scanner to Hospital General Universitario de Castellón by the Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición [Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition] and the Sociedad Valenciana de Endocrinología, Diabetes y Nutrición [Valencian Society of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Nutrition].

Please cite this article as: Merchante Alfaro AÁ, Garzón Pastor S, Pérez Naranjo S, González Boillos M, Blanco Dacal J, Maravall Royo FJ, et al. Inclusión de la inyección percutánea de etanol como primera línea de tratamiento de los quistes tiroideos sintomáticos. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:458–464.