In the past five years, healthcare organisation for trans people in Spain has changed as laws intended to protect sexual and gender diversity have been put in place. As a result, endocrinologists are not only on the front lines (understood as prescribing and following up gender-affirming hormone therapy) but also coordinating multidisciplinary healthcare for these individuals.

Advances in transgender medicine, the complexity of diverse trans identities and the impact of hormone therapy on quality of life and risk of middle- and long-term complications call for in-depth examination of a personalised biopsychosocial approach to trans people that requires specific training in this field of knowledge as well as updates on the concepts, terminology and drug treatments used.

En los últimos 5 años la organización de la atención sanitaria a las personas Trans en España ha cambiado en la medida que se han puesto en marcha leyes que tienen como objetivo la protección de la diversidad sexual y de género. Esto ha hecho que los endocrinólogos no sólo estemos en la primera línea (entendida como la prescripción y seguimiento del tratamiento hormonal de afirmación de género) sino que además coordinemos la atención sanitaria multidisciplinar de estas personas.

El avance de la Medicina Transgénero, la complejidad de las diversas identidades Trans así como el impacto del tratamiento hormonal en la calidad de vida y en el riesgo de complicaciones a medio y largo plazo, nos obliga a profundizar en un abordaje bio-psico-social e individualizado de las personas Trans que requiere de una formación específica en esta área de conocimiento así como de la actualización de los conceptos, terminología y tratamientos farmacológicos utilizados.

As trans people have made advances in their legitimate rights, they have gained greater relevance in the health field. Healthcare for trans people requires a holistic approach in which the endocrinologist plays a crucial role in coordinating and covering all the needs of these people.

More generally, research on the health of transgender people continues to tend to represent this group as somewhat homogeneous and lacking in diversity in areas such as ethnicity, gender identity and sexuality, when in clinical practice we find complexity and heterogeneity.

Transgender medicine1 is a new field of medical knowledge concerned with the multidisciplinary care of trans people, from a depathologising perspective,2 in order to achieve the best standards of health. This increased interest in transgender medicine is due in large part to heightened awareness of the medical needs of transgender people in the healthcare setting.

Advances in transgender medicine, the complexity of diverse trans identities and the impact of hormone therapy on the quality of life and risk of middle- and long-term complications in trans people force us to examine in more detail an individualised biopsychosocial approach that requires specific training in this area of knowledge, as well as updating on the concepts, terminology and drug treatments used.

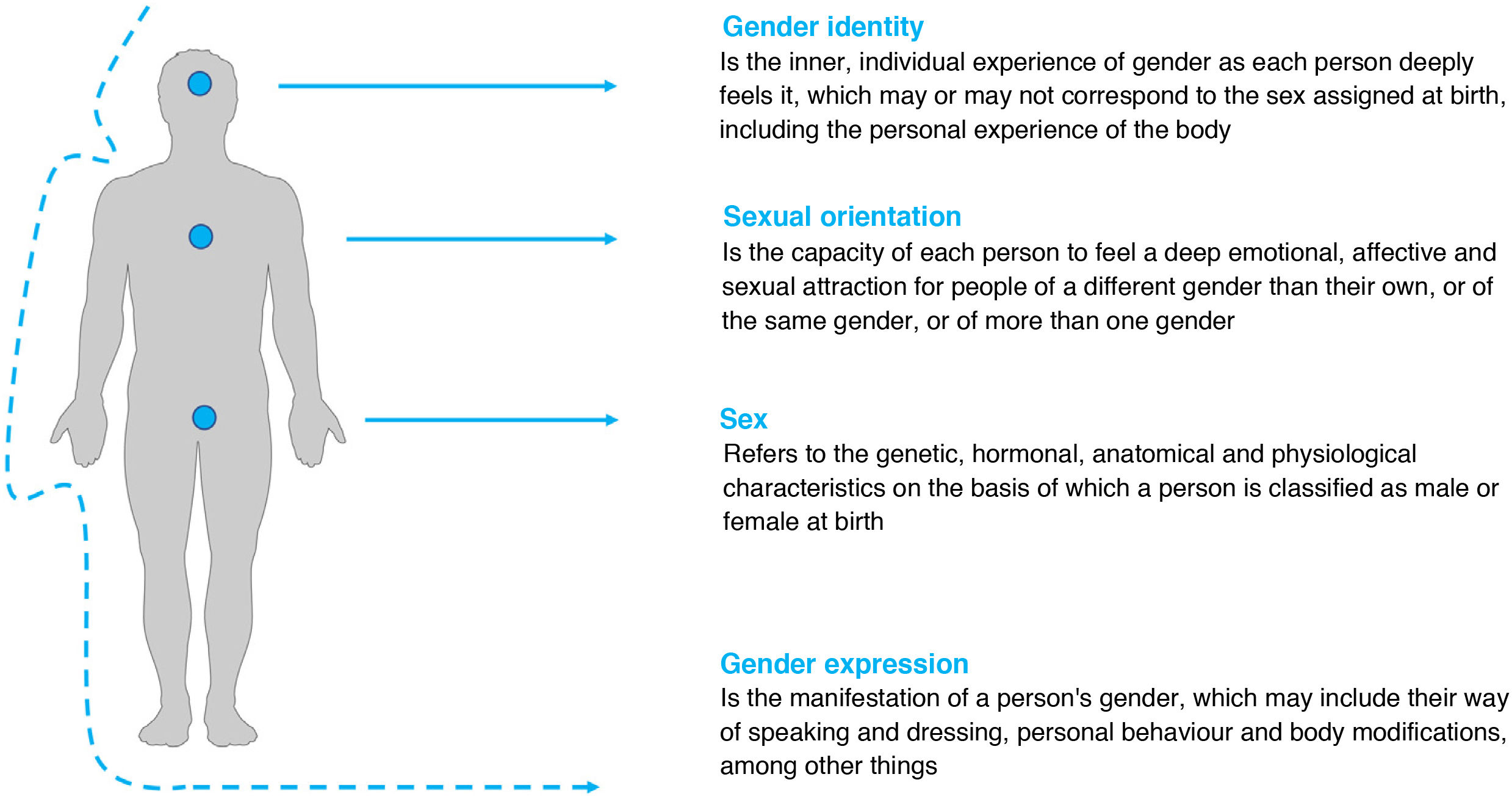

Relevant concepts in transgender medicineEach individual is a composite of gender and sexuality (Fig. 1). Both concepts have a biological component and a social construct. But it is these two basic concepts that usually cause enormous confusion, so it is necessary to establish the differences between them.

Gender3 refers to the social attributes and opportunities associated with being a man or a woman, and the relationships between men and women, and boys and girls. These attributes, opportunities and relationships are established and learned in society, are context- and time-specific, and may change — they are dynamic (for example, more and more men do housework). Gender determines what is expected, permitted and valued in a man or woman in a given context.

In more academic terms, we can identify three components of gender2:

- □

Gender identity

- □

Gender expression

- □

Biological sex

Gender identity3,4 refers to the inner individual experience of gender, as each person deeply feels it, which may or may not correspond to the sex assigned at birth, including the personal experience of the body. This experience of gender is intimate, diverse and complex, and answers the question "Who am I?".

Gender identity was previously considered as something dichotomous or binary (male or female), but nowadays it is understood as a spectrum where being a man or a woman are the extremes and in between there are different identities. This is called non-binary gender: a spectrum of gender identities and expressions stemming from a rejection of the binary assumption of gender as a strictly exclusive choice between man/male/masculine or woman/female/feminine, based upon the sex assigned at birth.5,6

The terms "cisgender" and "transgender" are used to describe the congruence or incongruence of one's felt gender identity with one's sex assigned at birth. Cisgender (the prefix cis is commonly used as a short form) describes a person whose gender identity is consistent with their sex assigned at birth. Transgender (the prefix trans is commonly used as a short form) is an umbrella term used to describe a person whose gender identity does not correspond with their sex assigned at birth.

Gender expression refers to a person's outward presentation of gender, and includes personal style, dress, hair, make-up, jewellery, vocal inflection and body language. It is typically categorised as feminine, masculine or androgynous. All people express a gender. It may be consistent or inconsistent with a person's gender identity.

Strictly speaking, the term sex3 refers to: the biological differences between men and women; their physiological characteristics; the sum of the biological characteristics that define the spectrum of humans as women or men; and the biological construct that refers to the genetic, hormonal, anatomical and physiological characteristics based upon which a person is classified as male or female at birth.

Sexuality is a central aspect of human beings that is present throughout their lives. It encompasses gender roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction. It is felt and expressed through thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviours, practices, roles and relationships.

While sexuality3,4 may include all of these dimensions, not all of them are always experienced or expressed. Sexuality is influenced by the interaction of biological, psychological, social, economic, political, cultural, ethical, legal, historical, religious and spiritual factors. Sexuality includes one of the concepts that creates the most confusion in healthcare and social settings: sexual orientation.

An individual's sexual orientation4,5 is independent of their biological sex or gender identity. It has been defined as each person's ability to feel a deep emotional, affective and sexual attraction for people of a gender other than their own, or of the same gender, or of more than one gender, as well as the ability to maintain intimate and sexual relationships with these people. The terms heterosexuality, homosexuality and bisexuality come under the heading of sexual orientation.

Transgender medicine terminologyConcepts related to gender identity have evolved at great speed in recent years. These concepts are dynamic, so constant updating is required.

Given the increased demand for healthcare from trans people, it is necessary to use a uniform language that enables people with different trans identities to be treated in a dignified and non-pathologising way.

According to the 2020 report "Las personas trans y su relación con el sistema sanitario"7 [Trans people and their relationship with the healthcare system] from the Federación Española de Lesbianas, Gais, Trans y Bisexuales (FELGTB) [Spanish Federation of Lesbian, Gay, Trans and Bisexual People]), 48% of trans people reported having experienced discriminatory or inappropriate treatment from healthcare staff, and the majority of them reported that said professionals were not aware of current gender identity-related terminology.

Table 1 lists the most important concepts and commonly used terminology in gender identity consultations, which are necessary for establishing adequate communication and a good doctor-user relationship.8–15

Basic concepts in transgender medicine and commonly used terminology.

| Concept/terms | Definition |

|---|---|

| Trans depathologisation | A theoretical/activist perspective that, rather than conceptualising gender diversity as a mental disorder, defends the recognition and protection of gender expression and identity as human rights. |

| LGBTQI+ | An initialism used as an umbrella term that attempts to encompass all genders and sexual minorities as well as identities outside of the cisgender and heteronormative binaries. |

| Gender dysphoria | According to the DSM-5, clinically significant distress from incongruence between felt gender identity and sex assigned at birth. |

| Transsexualism | According to the ICD-10, it is the desire to live and be accepted as a member of the opposite sex, which is often accompanied by feelings of discomfort or disagreement with one's own anatomical sex and the desire to undergo surgery or hormone therapy to make one's own body match the preferred sex as closely as possible. Term in disuse (currently the ICD-11 is in force). |

| Transsexuality | According to the ICD-10, a concept that indicates congruence between biological sex as defined by genitalia assigned at birth with conviction of being and identification with the opposite gender. Term in disuse (the ICD-11 is currently in force). |

| Transsexual | A person who has feelings of being born with the wrong physical sex. This term is also used to describe a person who presents physical changes due to hormone therapy and/or surgery. The use of this term is not recommended (transgender or trans are preferred). |

| Gender incongruence | According to the ICD-11, it is the marked, persistent incongruence or lack of conformity between a person's experienced gender and assigned sex, which often leads to a desire to transition in order to live and be accepted as a person of the experienced gender. The terms gender mismatch, gender discomfort and gender nonconforming are commonly used as synonyms. |

| Binary gender | It is the idea that gender is a strict choice between man/male/masculine and woman/female/feminine, based on the sex assigned at birth. |

| Non-binary gender | A spectrum of gender identities and expressions based on the rejection of the binary assumption of gender as a strictly exclusive choice between man/male/masculine and woman/female/feminine, based on the sex assigned at birth. |

| Misgendering | A term used when somebody identifies a trans person with a gender other than their felt gender. |

| Deadname | A term that refers to the name given at birth to a trans or non-binary person before they assumed their current gender identity (or any name with which they previously identified). |

| Deadnaming | The act of calling a person by the name given to them by their parents or legal guardians at birth, and not by their felt name. |

| Gender self-identification | A process in which a person legally and freely recognises their gender identity through an express declaration, with no need to present a medical diagnosis or meet any other requirement, such as the presence of witnesses. |

| Psychological support | Psychotherapy is viewed as a facilitating intervention in the process of personal growth and the development of one's own psychic autonomy, not as a technique for curing or diagnosing any type of mental disorder. |

| Gender-affirming approach | An approach to gender identity in social and healthcare settings that respects and accepts people's gender self-identification. |

| Transitioning | A process by which a person outwardly manifests their felt gender identity. While unique to each individual, the ultimate goal of transitioning is to be able to be seen, known and related to according to the core experience of self. |

| Gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) | The use of hormonal and non-hormonal medications to achieve physical changes consistent with the felt gender identity (binary or non-binary) based on the gender-affirmative approach. It is recommended that gender-affirming hormone therapy be used instead of cross-sex hormone therapy. |

| Gender-affirming surgery | Surgical procedures that align physical characteristics with the felt gender. This term is now preferred over sex reassignment surgery. |

ICD: International Classification of Diseases, published by the World Health Organization.

Endocrinologists are called upon to coordinate the comprehensive care of trans people and, therefore, we are responsible for part of the medical transition, which includes gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT).16 GAHT is the use of hormonal and non-hormonal medicines to achieve physical changes consistent with the patient's felt gender identity (binary or non-binary) as part of a gender-affirmative approach.

Starting GAHT is an important step for trans people and requires a prior biopsychosocial assessment, which enables the endocrinologist to prescribe safe treatment agreed upon with the person who wishes to start transitioning.

Most of Spain's Autonomous Communities (ACs) have laws protecting trans people that regulate and govern, among other things, the healthcare of these people. In the absence of a nationwide trans law, most ACs recognise gender self-identification (including Madrid, Andalusia and the Valencian Community), so a psychological/psychiatric report prior to GAHT is not needed (in much of the country), but psychological support is offered.

On 29 June 2021, the Spanish Council of Ministers presented a draft bill for the real and effective equality of trans people and for the guarantee of the rights of LGBTI people, which is under consideration and seeks to harmonise healthcare for trans people across Spain.

During a person's transition, it is necessary not only to prescribe treatment but also to support them, monitor the safety and efficacy of the treatment and guide them towards achieving the appearance with which they really identify. Informed consent (IC) must be obtained before GAHT is initiated.

IC is not just a patient/user right, it is also a mechanism that gives legal protection to endocrinologists prescribing GAHT. In the case of minors or people with disabilities, the consent form must be signed by BOTH parents or legal guardians (Spanish Penal Code: articles 155 and 156).17 It must be remembered that even if a parent does not have custody, they almost always retain parental authority. If one of the parents/guardians does not give their consent for the treatment, the GAHT cannot be started, since that would contravene the penal code. In this last circumstance in which the parents disagree, the final decision must be taken by a juvenile court, based on the best interests of the minor.

The free, conscious desire of the trans person to start hormone therapy is not enough to initiate GAHT; they must also not have any serious clinical or psychiatric conditions that put their own health or adequate compliance with treatment at risk. In this regard, it is very important not to fall into downplaying or exaggerating the risks involved. The latter (magnifying the risks associated with hormone therapy) is sometimes a major obstacle when starting GAHT.

Contraindications to this treatment can be classified according to the type of GAHT9,10,16:

Feminising GAHT:

- □

Active oestrogen-sensitive cancer (absolute contraindication).

- □

Unstable ischaemic heart disease (absolute contraindication).

- □

Severe cerebrovascular disease (stroke).

- □

Thrombophilia (hereditary or acquired) and/or history of thromboembolic events.

- □

Prolactinoma (prolactin-producing pituitary adenoma).

- □

Uncontrolled psychosis.

- □

Poorly controlled diabetes.

- □

Severe kidney or liver disease.

- □

Severe hypertriglyceridaemia.

- □

Psychiatric conditions that limit the ability to provide informed consent.

- □

Hypersensitivity (allergy) to one of the ingredients of the oestrogen formulation or other hormone preparations.

- □

Those with a strong family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer should be referred for genetic counselling to undergo screening for familial cancer in order to clarify their individual risk.

Masculinising GAHT:

- □

Pregnancy or breastfeeding (absolute contraindication).

- □

Active androgen-sensitive cancer (absolute contraindication).

- □

Unstable ischaemic heart disease.

- □

Severe cerebrovascular disease (stroke).

- □

Thrombophilia (hereditary or acquired, such as that associated with antiphospholipid syndrome) and/or history of thromboembolic events.

- □

Active endometrial cancer.

- □

Uncontrolled psychosis.

- □

Poorly controlled diabetes.

- □

Severe kidney or liver disease.

- □

Severe hypertriglyceridaemia.

- □

Psychiatric conditions that limit the ability to provide informed consent.

- □

Hypersensitivity (allergy) to one of the ingredients of the testosterone formulation or other hormone preparations.

- □

Those patients with a strong family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer should be referred for genetic counselling to undergo screening for familial cancer in order to clarify their individual risk.

Most of these contraindications are relative, in the sense that they require clinical stabilisation (controlling diabetes, decreasing triglycerides or waiting at least six months after a major cardiovascular event) before being able to start hormone therapy. They delay GAHT, but do not contraindicate it from the outset.

As regards complementary tests before starting GAHT, generally speaking, apart from laboratory tests (complete blood count, biochemical and basic clotting tests, gonadal profile), other complementary tests (such as karyotype test, thrombophilia test and breast/pelvic ultrasound) are not routinely recommended,9,10 unless the medical history, personal or family history and/or physical examination suggest the existence of comorbidities.

Ordering unjustified complementary tests is one of the factors that delay the start of hormone therapy and increase healthcare costs.

General considerations- 1)

The goals of gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) in trans people are determined by various factors, including: age, ability to consent to treatment, pre-existing health problems, risk of future development of diseases, access to care and user desire during the transition.

- 2)

Trans people should be asked about gamete preservation before starting GAHT and given advice and guidance on realistic expectations of masculinisation/feminisation, and when such changes will begin to occur.

- 3)

The first consultation should include identification of potential risks for GAHT: smoking, alcohol consumption and risk behaviours, family history of cancer (gynaecological, breast and prostate), cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia.

- 4)

It is advisable to offer psychological support to manage expectations before, during and after transitioning.

- 5)

Physical examination (of the breasts and genitals) can cause anxiety and discomfort; it must always be performed only with the explicit consent of the person and be approached in a sensitive, respectful manner.

- 6)

Signed inform consent must always be obtained (in the case of minors under 18 years of age and people with intellectual disabilities, the consent form must also be signed by both parents and/or legal guardians).

Tables 2 and 3 summarise the hormone preparations commonly used in masculinising and feminising GAHT,18–27 including some important comments on their safety.

Drugs used in feminising GAHT.

| Antiandrogens | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Route | Presentations | Dose | Observations |

| GnRH analogues | ||||

| Triptorelin | IM | 3.75-mg and 7.25-mg vial | 3.75mg/28 days | Good tolerance. Commonly used in adults in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. In Spain, it is used in a minority of cases due to its price, although it is subsidised by some ACs. |

| 7.25mg/3 months | May prolong QT interval. | |||

| Progestogens | ||||

| Cyproterone acetatea | Oral | 50-mg tablet | 12.5−25mg/day | Inhibits secretion of gonadotropins and blocks androgen receptors. Assess its contraindications. |

| Dienogest | Oral | 2-mg tablet | 2−3mg/day | Progestagen with antiandrogen activity (40–60% compared to cyproterone). Preferably use in combination with oestradiol valerate (some combinations contain ethinyloestradiol) |

| Drospirenone | Oral | 0.5-mg and 3-mg tablets | 0.5−3mg/day | Progestagen with antiandrogen activity (40−60% compared to cyproterone) and aldosterone antagonist (as it is derived from spironolactone. Preferably used in combination with oestradiol valerate (some combinations contain ethinyloestradiol). |

| Androgen receptor antagonists | ||||

| Spironolactoneb | Oral | 25-mg and 100-mg tablets | 100−400mg/day | Monitor blood pressure. Inexpensive. Risk of liver toxicity. Diarrhoea and rash. |

| Flutamide | Oral | 250-mg tablet | 250−500mg/day (1−2 doses) | Risk of liver toxicity and thromboembolic disease. Increases oestradiol (increased risk of DVT). Adjust dose of oestrogens and anticoagulants. May prolong QT interval. |

| Bicalutamidec | Oral | 50-mg tablet | 25−50mg/day | Contraindicated in interstitial lung disease. Liver toxicity. |

| 5α-reductase inhibitors | ||||

| Finasteride | Oral | 5-mg tablet | 5mg/day | Useful following gonadectomy. Contains lactose. Monitor PSA. |

| Dutasteride | Oral | 0.5-mg tablet | 0.5mg/day | Interaction with ritonavir/indinavir and calcium channel blockers. Monitor PSA. |

| Feminising preparations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active ingredient | Route | Presentations | Dose | Observations |

| Micronised oestradiol | Oral/sublingual | 2-mg tablets | Oral: 2−4mg/day in two doses. | Of choice when starting GAHT: a plasma oestrone-to-oestradiol ratio of 5:1 promotes breast bud formation. |

| Oestradiol valerate | Oral/sublingual | 1-mg and 2-mg tablets in combination with progestagens. | SL: 0.5−4mg/day in two doses. | The sublingual route (as an alternative to the transdermal or intramuscular/subcutaneous route) is recommended from Tanner stage 3−4 of breast development to promote glandular hyperplasia). |

| IM/SCd | Ampoules in concentrations of 5, 20 and 40mg/ml | 2−4mg weekly | 100% bioavailability. Achieves suppression of testosterone secretion without requiring antiandrogens. | |

| Ethinyloestradiol | Oral | 0.02−0.03mg tablets combined with progestagens | 0.02−0.03mg/day (20−30μg/day) | Always as a last resort: Increased risk of DVT. In regular clinical practice, it is not possible to measure plasma levels. |

| Transdermal | Extended-release patch | |||

| 33.9μg/24h in combination with progestagens (for 7 days). | ||||

| Oestradiol hemihydrate (patches)e | Transdermal | Patches of 25, 50, 75 and 100μg/24h (for 3−4 days). | 100−200 μg/day | Low risk of DVT. |

| Oestradiol hemihydrate (gel)e | Gel at a concentration of 0.6mg/g | 3−6mg/day | ||

| Oestradiol hemihydrate (spray)e | Each spray administers 1.53mg | 6−9mg/day (in 2−3 doses) | Low risk of DVT. With this formulation, lower oestradiol peaks are obtained – up to 60% less (versus gel). | |

| Micronised progesteronef | Oral | 100-mg and 200-mg capsules | 100−200mg oral/day | Do not confuse progesterone with medroxyprogesterone. This medicine contains peanut and/or soybean oil and therefore should not be used in people with allergies to these foods. |

| Given the limited evidence of its effects on the growth of mammary alveoli, its widespread use is not recommended in trans/AMAB women. | ||||

| May increase risk of thrombosis. | ||||

| Rectal | 100mg rectally at bedtime | |||

GAHT: gender-affirming hormone therapy; SL: sublingual; IM: intramuscular; SC: subcutaneous; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; AMAB: assigned male at birth.

ACs: Autonomous Communities; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; CHF: congestive heart failure; PSA: prostate specific antigen.

Cyproterone acetate: contraindicated in severe depression, liver disease, thromboembolic disease or diabetes mellitus with microangiopathic involvement. May increase the risk of meningiomas: monitor cumulative dose.

Spironolactone: although uncommon, if the patient develops a skin rash or general malaise, treatment should be suspended and the patient should be referred to the emergency department immediately (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms [DRESS] syndrome).

Bicalutamide: contraindicated if there is a history of ischaemic heart disease or chronic heart failure. Do not use in interstitial lung disease, liver disease or prolonged QT interval (as with flutamide). Interaction with ritonavir/indinavir and calcium channel blockers (verapamil and diltiazem). It should not be used as the first option, given its potential adverse effects.

Oestradiol valerate injection: commonly used in the US and Latin America, as well as in Eastern Europe. There are currently no formulations on the market in Spain.

Hormonal preparations available for masculinising GAHT.

| Masculinising hormonesa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active ingredient | Route | Presentation | Dose | Observations |

| Testosterone cypionate | IM | 100-mg and 250-mg ampoule | 100mg every 14 days | Short-acting preparations. Does not mimic circadian rhythm. |

| 250mg every 21 days | ||||

| SCb | 50−100mg SC weekly | The same preparation is used intramuscularly (off label). | ||

| Testosterone undecanoate | IM | 1-g ampoule | 1g/3 months | First dose of 1g IM, second dose at 6 weeks and then 1g IM every 3 months. |

| Testosterone (gel)c | Transdermal | 50-mg/5-g sachet | 1 sachet per day | Risk of transfer to partner |

| 20mg/g (2%) | 4−6 applications/day (40−60mg) | 1 application=0.5g of gel=10mg of testosterone | ||

| 16.2mg/g | 2−3 applications/day (40.5−60.75mg) | 1 application=1.25g of gel=20.25mg of testosterone | ||

| Other preparations for use in trans men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active ingredient | Route | Presentation | Dose | Observations |

| Progestagens: to stop menstruation or as contraceptives | ||||

| Norethisterone | Oral | 5-mg and 10-mg tablets | 5−10mg/day | Statins increase its plasma concentration. |

| Medroxyprogesteroned | Oral | 5-mg and 10-mg tablets | 5−10mg/day | Administer in the first five days of the menstrual cycle. Does not appear to increase the risk of thrombosis. |

| IM | Depo-Progevera [Depo-Provera] 150mg/ml ampoule. | Every three months | Does not appear to increase the risk of thrombosis. | |

| Micronised progesterone | 100-mg and 200-mg capsules | 200−300mg/day | This medicine contains peanut and/or soybean oil and therefore should not be used in people with allergies to these foods. | |

| Etonogestrel | Intradermal implant | 68-mg implant | Every three years | Menstruation may continue up to three months after placement. |

| Levonorgestrel | Intrauterine implant | Implant with an intrauterine release system of 0.02mg every 24h. | Every five years | Can cause headache |

| Aromatase inhibitors | ||||

| Anastrozole | Oral | 1-mg tablet | 1mg/day | May be beneficial in trans men with obesity and persistent menstruation. |

| Letrozole | Oral | 2.5-mg tablet | 2.5mg/day | |

IM: intramuscular; SC: subcutaneous.

Prior to testosterone therapy, it is advisable to measure ®-HCG (pregnancy test) and screen for sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome (SAHS) with tools such as the STOP-BANG questionnaire.

Subcutaneous use (cypionate weekly): same preparation as IM, in which SC use is off-label. Increasingly used, as it yields more stable blood testosterone levels and possibly fewer side effects. It could be considered the route of choice if not for the inconvenience of weekly administration and the fact that it has to be drawn using an insulin or 1-ml syringe.

The use of testosterone gel in individuals under 18 years of age is off-label It should not be applied to the genital area (penis, testicles, clitoris or vulva) because its high alcohol content can cause local irritation.

Medroxyprogesterone. Precautions: it is necessary to take into account, as well as investigate in a timely manner, the history or appearance of the following conditions: migraine or unusual severe headache, acute visual alterations of any type, pathological changes in liver function or hormone levels.

The initiation of gender-affirming hormone therapy is as important as follow-up to ensure changes occur at a timely pace, to adjust treatment, and to monitor/identify any related adverse effects.

Although the various guidelines recommend variable follow-up times, they all agree that most of the serious adverse effects associated with GAHT occur in the first year, so a check-up every three to six months is recommended. In any case, it should be clarified that most of those recommendations (which include GAHT) are based on evidence that is of low quality or has not been directly established at the present time, and the drugs are used off-label.26,27 Therefore, these are high-priority research areas.

The demand for GAHT has increased in recent years, mostly driven by adolescents and young adults. Meanwhile, there is a minority of people on GAHT who may ask to detransition28: a procedure to reverse the changes made in the gender reassignment process, whether medical, social or administrative. Detransitioning may or may not be associated with identity desistance.

However, it is believed that the existence of cases of detransitioning does not invalidate the need for public, specialised healthcare for these people, from which the majority clearly benefit, with psychological support being a useful tool throughout the transitioning process.

GAHT in non-binary trans peopleThe few existing studies21 have indicated that non-binary trans people represent 25−35% of trans people attending transgender medicine consultations. In Spain,24 one in four people under the age of 30 identifies with a non-binary identity.

What they want from GAHT can range from the complete loss of secondary sexual characteristics (demasculinisation or defeminisation) to the complete acquisition of the appearance of the felt gender identity.25 In this regard, there may even be people who do not need GAHT to transition (agender or bigender).

Being aware of the reality of this group is key to providing adequate care in transgender medicine consultations. Before indicating GAHT in this group, it is very important to know the desires and expectations of each person in depth: to individualise.

ConclusionsTransgender healthcare is a rapidly growing field, with an exponential increase in published research in recent years. Research and practice in transgender medicine have not always been sensitive to trans people, since most studies have focused on a biological cause rather than on improving their health.

At present, there are high-priority research topics in this field, such as the causes of excess morbidity and mortality, cardiovascular risk and cancer, the impact of GAHT on mental health, ageing, and sexual and reproductive health. Urgent updates are also needed to Spanish clinical practice guidelines29 for managing gender identity, since the existing ones have become outdated and, in some respects, run contrary to the current approach to sexual and gender diversity.

Advances in transgender medicine, the complexity of diverse trans identities, the impact of hormone therapy on quality of life and the risk of medium and long-term complications for trans people force us to study in more detail an individualised biopsychosocial approach. Endocrinologists have historically been at the forefront of hormone therapy, but as the demand, diversity and complexity of our users increase, we need to be able to offer a holistic view of their needs.

FundingI have not received any funding for this review.

Conflicts of interestThe author declares that he/she has no conflicts of interest.