In routine clinical practice, it is common for hospitalised patients who require antibiotic treatment to state that they are allergic to antibiotics or to present a possible allergic event during their administration. Although we do not have data on the actual incidence of antibiotic allergies, there are studies which indicate that in both children and adults (the general population), the prevalence of hypersensitivity reactions to antibiotics ranges from 1 to 10%.1,2 Our objective was to evaluate the prevalence of patients allergic to antibiotics in our tertiary hospital, and to determine the main antibiotics involved and the percentage of patients who were eventually able to receive the right antibiotic. To that end, a retrospective study was conducted in our tertiary hospital, in which all referrals received by the allergy department in 2016 and 2017 relating to antibiotic allergies were included. In addition, follow-up information was collected from outpatient allergy consultations attended by patients who were deemed to require them after being discharged from hospital.

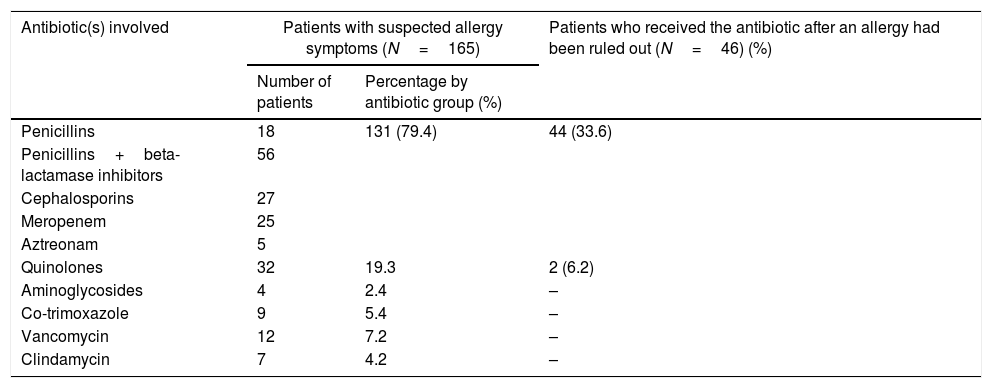

A total of 222 referrals (49.5% males and 50.5% females, mean age: 63.9 years) were carried out. Of these, 108 patients (48.6%) reported a history of allergy upon admission, of which only 27 (25%) provided prior allergy tests. The manifestations were mainly cutaneous (75%), followed by anaphylaxis (1.8%) and DRESS (0.9%). The remaining patients did not recall or know how to identify the reaction. The main antibiotic groups involved were beta-lactams (83.3%), mainly penicillins, followed by aminoglycosides, quinolones, co-trimoxazole and sulphonamides. Furthermore, 165 referrals (74.3%) stemmed from patients who presented with suspected allergy symptoms during their hospital stay, with assessment by the allergy department being requested. Once again, beta-lactams were the main antibiotics involved. Allergy was ruled out in 64 patients by means of allergy testing. The study performed consisted of a targeted medical history, skin tests and an oral provocation test in patients in whom it was deemed necessary. 46 of them were eventually able to receive the medicine which had initially been prohibited, as detailed in Table 1. Finally, a deferred study was proposed at hospital discharge in 188 patients (84.6%), 84 of whom attended the consultation (44.6%). In this group, allergy was ruled out in 35 patients (41.6%) and proven in 21 patients (25%). Once again, beta-lactams were the most frequently involved antibiotics. There were 19 non-conclusive studies (22.6%) and nine patients are still under study (10.7%).

Antibiotics suspected of causing allergy symptoms during hospital admission.

| Antibiotic(s) involved | Patients with suspected allergy symptoms (N=165) | Patients who received the antibiotic after an allergy had been ruled out (N=46) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | Percentage by antibiotic group (%) | ||

| Penicillins | 18 | 131 (79.4) | 44 (33.6) |

| Penicillins+beta-lactamase inhibitors | 56 | ||

| Cephalosporins | 27 | ||

| Meropenem | 25 | ||

| Aztreonam | 5 | ||

| Quinolones | 32 | 19.3 | 2 (6.2) |

| Aminoglycosides | 4 | 2.4 | – |

| Co-trimoxazole | 9 | 5.4 | – |

| Vancomycin | 12 | 7.2 | – |

| Clindamycin | 7 | 4.2 | – |

In our review, half of the referrals made were for patients who mentioned a history of antibiotic allergy. The main group involved and the manifestations cited coincide with what is reported in the literature2 (mainly beta-lactams and skin manifestations), and most patients did not provide previous allergy tests. A detailed medical history, in which the patient is questioned about his/her symptoms, possible concomitant factors and circumstances accompanying the previous event, is fundamental in order to rule out allergic symptoms related to other clinical entities. In many cases, a detailed medical history is sufficient to steer us towards an intolerance or adverse drug reaction, rather than towards allergy symptoms. Recording a false antibiotic allergy in a patient's medical history may lead to the prescription of other more expensive drugs or drugs which are less effective.3–6 The administration of beta-lactams, the main group of antibiotics involved in suspected allergies in our hospitalised patients, was eventually possible in the majority after they had been reviewed by the allergy department.7 Likewise, the outpatient study also allowed allergies to be ruled out in a significant number of patients. Possible limitations of this study are its retrospective nature and that, by assessing hospitalised patients, allergies were potentially overestimated because of the patients’ specific comorbidities, as well as polymedication due to the risk of drug interactions that this entails.

In conclusion, a detailed medical history of the patient, together with assessment by the allergy department, are fundamental to confirm or rule out allergy to an antibiotic group, allowing, in the majority of cases, its subsequent use and preventing the administration of more expensive and less optimal treatments.

Please cite this article as: Falces-Romero I, Hernández-Martín I, Fiandor A, Rico-Nieto A. Alergia a antibióticos: perspectiva desde un hospital de tercer nivel. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019;37:350–351.