This study aims to describe and analyze the characteristics of aged people who are living with HIV (APHIV) and evaluate their association on the comorbidities they currently have.

MethodsCross-sectional analysis of APHIV under active follow-up at the Infectious Diseases Unit of the University Clinical Hospital of Santiago de Compostela. Demographic and clinical data were analyzed, along with their association with the development of comorbidities in this population. A correlation and multiple linear regression analysis were performed for this purpose.

ResultsEighty-five APHIV, 65 males and 20 females, with an average age of 69 years (IQR 8) and a duration of living with HIV of 17 years (SD 7), were studied. 41% of them had their initial diagnosis with AIDS. The most common comorbidities are hypertension and dyslipidemia in 55% and 52%, respectively. 40% of APHIV take at least 5 medications. 35% have received more than 5 lines of antiretroviral treatment. At the time of analysis, all APHIV have an undetectable viral load. No significant association was observed between the number of comorbidities and various characteristics of APHIV; however, a weak correlation was noted among age, the cumulative number of antiretroviral treatments received throughout their lives, and the number of comorbidities.

ConclusionsThis analysis highlights the substantial burden of comorbidities and polypharmacy experienced by APHIV. Further studies are needed to better understand the characteristics and variables influencing their development.

Este trabajo pretende describir y analizar las características de las personas mayores de 65 años que conviven con VIH (PMVIH) y valorar su asociación con las comorbilidades que presentan en la actualidad.

MétodosAnálisis de corte transversal de PMVIH a seguimiento activo en la Unidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas del Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela. Se analizaron los datos demográficos y clínicos, su asociación con el desarrollo de las comorbilidades presentes en esta población y se llevó a cabo un análisis de correlación y regresión lineal múltiple.

ResultadosOchenta y cinco PMVIH, 65 varones y 20 mujeres con una edad media de 69 años (RIC 8) y un periodo de convivencia con VIH de 17 años (DE 7). El 41% debutó con SIDA. Las comorbilidades más frecuentes son hipertensión y dislipemia en un 55% y 52%. El 40% de las PMVIH toman al menos 5 fármacos. El 35% ha recibido más 5 líneas de tratamiento antirretroviral. En el momento del análisis todas las PMVIH tenían una carga vírica indetectable. No se observó una asociación entre el número de comorbilidades y las diferentes características de las PMVIH; pero se apreció una correlación débil, entre la edad, el número de tratamientos antirretrovirales recibidos a lo largo de su vida y el número de las mismas.

ConclusionesEste análisis pone de manifiesto la importante carga de comorbilidades y polifarmacia que sufren las PMVIH. Siendo necesarios más estudios para determinar mejor las características y variables que influyen su desarrollo.

Since the advent of triple antiretroviral treatment in 1996, the life expectancy of people living with HIV (PLHIV) has increased. This, coupled with new diagnoses in older people, means an increase in the population over 65 years of age living with HIV, with estimates that by 2030, it will represent 23% of all PLHIV.1

There is evidence of accelerated ageing, more comorbidities, earlier onset of comorbidities and increased frailty in this population group of older PLHIV.2–5

The aim of our study was to characterise the older PLHIV in our cohort and determine whether there was any association between their gender, characteristics at diagnosis or the antiretroviral treatment (ART) received over the years and their current comorbidities.

MethodsCross-sectional analysis of PLHIV aged 65 or older in March 2023, under active follow-up in the Infectious Diseases Unit of the University Clinical Hospital of Santiago de Compostela.

The variables at the time of diagnosis were collected by reviewing the medical records and included year, viral load, CD4+ lymphocyte count and AIDS diagnosis, as well as the main comorbidities (hypertension [HT], dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, lipodystrophy, obesity, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, psychiatric disorders, neurological disorders and gastrointestinal disorders, including cirrhosis). We also recorded the treatments used for the comorbidities, grouping some similar categories together to help consolidate the analysis, such as drugs for heart failure or lipid-lowering drugs.

We recorded the total number of ART lines they had been on over the years, as well as their current treatment, its dosage and the number of times over the years they had developed resistance.

A descriptive analysis was performed to examine the characteristics of the participants, using percentages for categorical variables, mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables with a normal distribution, and the median and interquartile range (IQR) for those with a non-normal distribution. For the comparison of qualitative variables, Pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used, as appropriate, and for continuous variables, Student’s t test, the Mann Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis test. In all cases, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We also performed a correlation analysis using Spearman’s test and a multivariate linear regression, where the dependent variable was the number of comorbidities and the independent variables were those which had achieved statistical significance (p < 0.05) in the correlation test. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics for MAC v25.0 (SPSSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Our study followed the standards established in the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and had the approval of the Comité Autonómico de Ética de Investigación médica de Galicia [Autonomous Committee for Medical Research Ethics of Galicia], registration number, 2018/019.

ResultsA total of 85 older PLHIV were included, 65 men and 20 women, with a median age of 69 (IQR 8). The mean number of years with HIV was 17 (SD 7 years). In all, 26% of the older PLHIV were diagnosed before 1996.

At the time of diagnosis, 46% had fewer than 200 CD4+/μl and 73% had a viral load of more than 100,000 copies/ml. A total of 35 patients (41%) had their initial diagnosis with AIDS, tuberculosis being (12%) the most common defining disease.

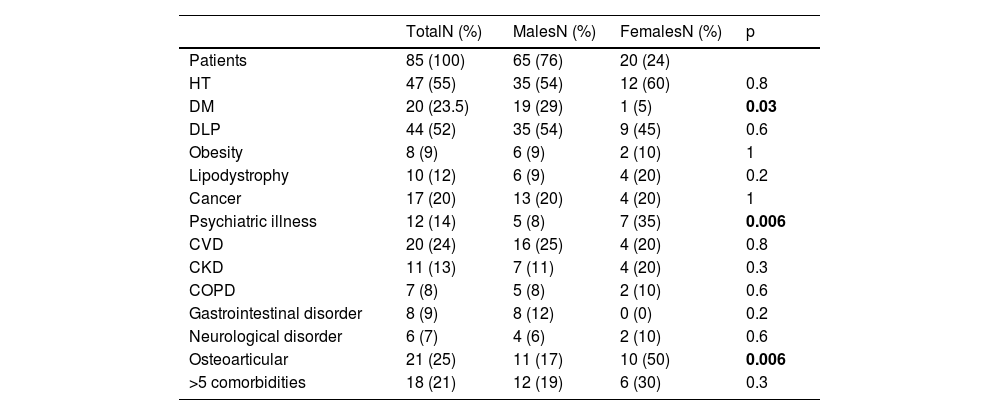

In terms of comorbidities, 21% had five or more, with HT (55%) being the most prevalent, followed by dyslipidaemia and osteoporosis, at 52% and 25% respectively. Significant differences between males and females were observed in diabetes mellitus, psychiatric disorders and osteoporosis. The comorbidities are described in more detail in Table 1.

Comorbidities in the people participating in the study.

| TotalN (%) | MalesN (%) | FemalesN (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 85 (100) | 65 (76) | 20 (24) | |

| HT | 47 (55) | 35 (54) | 12 (60) | 0.8 |

| DM | 20 (23.5) | 19 (29) | 1 (5) | 0.03 |

| DLP | 44 (52) | 35 (54) | 9 (45) | 0.6 |

| Obesity | 8 (9) | 6 (9) | 2 (10) | 1 |

| Lipodystrophy | 10 (12) | 6 (9) | 4 (20) | 0.2 |

| Cancer | 17 (20) | 13 (20) | 4 (20) | 1 |

| Psychiatric illness | 12 (14) | 5 (8) | 7 (35) | 0.006 |

| CVD | 20 (24) | 16 (25) | 4 (20) | 0.8 |

| CKD | 11 (13) | 7 (11) | 4 (20) | 0.3 |

| COPD | 7 (8) | 5 (8) | 2 (10) | 0.6 |

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 8 (9) | 8 (12) | 0 (0) | 0.2 |

| Neurological disorder | 6 (7) | 4 (6) | 2 (10) | 0.6 |

| Osteoarticular | 21 (25) | 11 (17) | 10 (50) | 0.006 |

| >5 comorbidities | 18 (21) | 12 (19) | 6 (30) | 0.3 |

DLP: dyslipidaemia; DM: diabetes mellitus; CVD: cardiovascular disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; HT: hypertension.

In bold: statistically significant results with a p value <0.05.

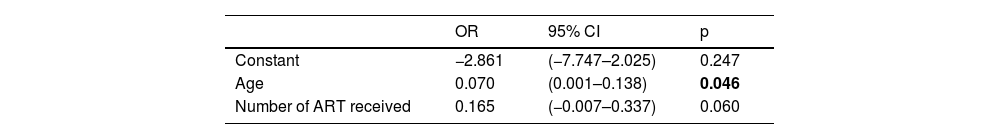

No statistically significant differences were observed between the number of years living with HIV, the diagnosis of AIDS, viral load, total number of CD4+ lymphocytes at diagnosis, being diagnosed before the advent of triple antiretroviral therapy, the number of treatments over the years, having five or more comorbidities or the total number of comorbidities. In the correlation study, age and the number of ART received showed a weak (correlation coefficient of 0.27 and 0.25 respectively) but significant relationship with the number of comorbidities. They were therefore included in the multiple linear regression model (Table 2) as independent variables, which would explain 6.8% of the comorbidities.

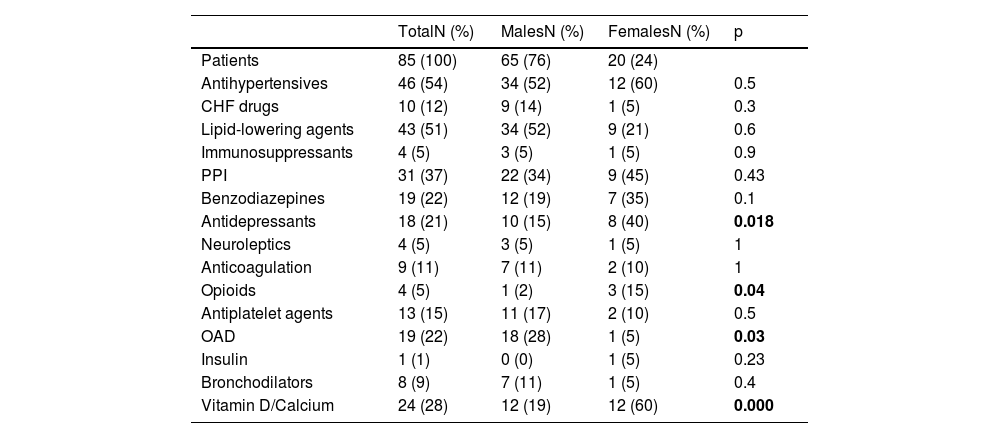

Our older PLHIV were taking an average of three drugs (SD 2) for their concomitant conditions, the maximum number of drugs being eight, with 40% on at least five (Table 3). In all, 54% were on antihypertensive drugs, 51% on lipid-lowering drugs, 22% on benzodiazepines and 21% on antidepressants.

Non-ART drugs the older people with HIV were taking.

| TotalN (%) | MalesN (%) | FemalesN (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 85 (100) | 65 (76) | 20 (24) | |

| Antihypertensives | 46 (54) | 34 (52) | 12 (60) | 0.5 |

| CHF drugs | 10 (12) | 9 (14) | 1 (5) | 0.3 |

| Lipid-lowering agents | 43 (51) | 34 (52) | 9 (21) | 0.6 |

| Immunosuppressants | 4 (5) | 3 (5) | 1 (5) | 0.9 |

| PPI | 31 (37) | 22 (34) | 9 (45) | 0.43 |

| Benzodiazepines | 19 (22) | 12 (19) | 7 (35) | 0.1 |

| Antidepressants | 18 (21) | 10 (15) | 8 (40) | 0.018 |

| Neuroleptics | 4 (5) | 3 (5) | 1 (5) | 1 |

| Anticoagulation | 9 (11) | 7 (11) | 2 (10) | 1 |

| Opioids | 4 (5) | 1 (2) | 3 (15) | 0.04 |

| Antiplatelet agents | 13 (15) | 11 (17) | 2 (10) | 0.5 |

| OAD | 19 (22) | 18 (28) | 1 (5) | 0.03 |

| Insulin | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0.23 |

| Bronchodilators | 8 (9) | 7 (11) | 1 (5) | 0.4 |

| Vitamin D/Calcium | 24 (28) | 12 (19) | 12 (60) | 0.000 |

OAD: oral antidiabetic drugs; CHF drugs: drugs used in the treatment of heart failure; PPI: proton pump inhibitors; PLVIH: people living with HIV.

In bold: statistically significant results with a p value <0.05.

Among those with HT, 89% were on treatment, as were 95% of those with diabetes and 78% of those with dyslipidaemia.

Overall, 65% of older PLHIV have had between one and five different treatment regimens and 35%, more than five. In addition, 23% developed a mutation associated with antiretroviral resistance; these mutations were not related to being diagnosed before 1996. At the time of the analysis, 89% were on ART consisting of a single daily tablet and 100% had an undetectable viral load.

DiscussionOlder PLHIV represent an increasingly larger proportion of PLHIV. This increase in longevity brings with it an increase in the development of age-related comorbidities, which seem to occur at younger ages and in greater numbers than in people without HIV.6

In our sample, the most prevalent comorbidities were HT and dyslipidaemia, found in more than 50% of older PLHIV, proportions similar to other clinical series.5,7 These disorders, like diabetes mellitus, obesity or smoking, contribute to increasing cardiovascular risk, which in older PLHIV is already a high risk in itself, given the endothelial damage, chronic inflammatory process and alteration of the intestinal barrier caused by HIV, and the toxic effect of some classic ART.2,8 Overall, 24% of the older PLHIV in our sample had some established cardiovascular disease. It is because of this that we must pay special attention to correcting and improving these cardiovascular risk factors in older PLHIV. Although the treatment rates for these disorders are good, as can be seen in the results, there is still a small margin for improvement that we must pursue.

Osteoporosis is a common comorbidity in PLHIV, even at an early age, and can represent a four-fold increased risk of hip fracture compared to people not living with HIV.9 This increased risk is not only due to the infection itself, but also to side effects of drugs such as tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. A quarter of our sample had osteoporosis, being significantly more common among women. This proportion is higher than other published series and is related to the fact that, unlike the cited articles, we focused on the population over 65 years of age, in which osteoporosis is more common.7

A total of 40% of our older PLHIV were taking at least five drugs, with the associated increase in morbidity and mortality and a greater risk of adverse drug reactions and interactions between drugs, both ART and non-ART,10,11 in a population which already has a significant burden of comorbidity and in which these adverse reactions can lead to serious consequences. It is striking that 33% of older PLHIV take benzodiazepines, neuroleptics or antidepressants, when only 14% are diagnosed with a psychiatric illness. Moreover, these disorders are significantly more common in women, with a similarly higher proportion of women receiving antidepressant therapy. These data should make us reflect on the probable misdiagnosis and mismanagement of these disorders, the potential interactions and unwanted effects of these drugs and the stigma and discrimination that HIV still entails, especially in women.12

In our analysis, no association was found between the number of comorbidities and the different characteristics of older PLHIV, but, although weak, a correlation was observed between the comorbidity burden, age and the number of ART treatments received throughout the patient’s life. This is surely because our study focuses on people over 65 with long survival, in whom age, in itself, is a factor for the development of other disorders. The majority were diagnosed after the advent of triple antiretroviral therapy. Nevertheless, the larger number of ART taken over the patient’s lifetime, the greater number of side effects. Even so, these two variables would only explain 6.8% of the comorbidities found in the older PLHIV in our sample, highlighting the need to continue investigating the rest of the factors involved.

This analysis shows that HIV is now a chronic disease and that older PLHIV bear a large burden of comorbidity and polypharmacy. We therefore need to ensure that the assessment and treatment of older PLHIV is as personalised as possible, in order to improve their health and quality of life.

As this is a cross-sectional study with a small sample size, our main limitations lie in the sample size and the loss of variables that would be of interest to analyse, such as frailty, physical exercise, or toxic habits, which play a clear role in the development of comorbidities and the acceleration of ageing in older PLHIV. It would also be very useful to know the exact date of diagnosis of the main disorders analysed in order to perform a survival analysis. These are all elements that we need to take into account in future projects.

FundingThis study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestNone.

We would like to thank all the staff of the Infectious Diseases Unit of the University Hospital Complex of Santiago de Compostela for their collaboration. Without them, it would not be possible to improve the quality of life of people living with HIV.