Since 2014, an increase in the number of cases of fever associated with rhabdomyolysis of unexplained cause has been reported in African refugee immigrants arriving on the Italian coast after voyaging across the Mediterranean. These migrants come mostly from East Africa, Nigeria and Libya, and some from Gambia.1–3 This syndrome has been reported in up to 1% of 1500 refugees treated in a hospital in the Italian region of Calabria over three years.2 We present the case of an immigrant woman from West Africa treated in our hospital for fever and rhabdomyolysis of unknown cause after making the crossing of the Strait of Gibraltar to arrive in Spain.

This was a 38-year-old patient from Conakry in Guinea, from where she had set off two months earlier, arriving in Spain a week earlier across the Strait and subsequently having been transferred to the Zaragoza Red Cross. Four days after her journey, the patient developed a fever of 39 °C, fatigue and aching joints and muscles, particularly in her neck, with no apparent focus of infection. She reported no pharmacological, toxic substance, drug or sea water intake; there was also no history of trauma or overexertion in the previous 72 h. On examination, her vital signs were normal, and she had slight diffuse pain across her abdomen, with no hepatomegaly or splenomegaly palpated. Cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy smaller than 2 cm was detected. Blood analysis showed ions and kidney function to be normal throughout her stay in hospital. The patient had a pyrexia of 39 °C and elevation of rhabdomyolysis enzymes [creatine kinase (CK) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)] and liver enzymes [glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminase (GOT) and glutamate-pyruvate transaminase (GPT)] (Table 1), for which she was started on treatment with antipyretics and fluid therapy. The fever disappeared after 24 h and urinary alkalinisation was not considered necessary, as the patient's CK levels were not very high and were showing a tendency to decrease (Table 1). A study of haemoglobinopathies and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) activity was performed with no abnormal findings. Malaria, syphilis, HIV, hepatitis C, hepatitis B, hepatitis A, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), urinary tract infection and bacteraemia were all ruled out; thyroid hormones were normal. In the absence of suggestive symptoms, the patient was not investigated for the presence of coxsackievirus or adenovirus infection.

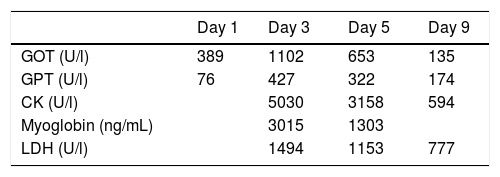

Changes in transaminases and rhabdomyolysis enzymes during the course of the admission.

| Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 5 | Day 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOT (U/l) | 389 | 1102 | 653 | 135 |

| GPT (U/l) | 76 | 427 | 322 | 174 |

| CK (U/l) | 5030 | 3158 | 594 | |

| Myoglobin (ng/mL) | 3015 | 1303 | ||

| LDH (U/l) | 1494 | 1153 | 777 |

CK: creatine kinase; GOT: glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminase; GPT: glutamate-pyruvate transaminase; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase.

Many acquired and inherited causes of rhabdomyolysis have been described. It is a potentially serious condition which can lead to acute kidney injury and be a source of major complications. Many infections have been associated with this syndrome, most commonly influenza viruses, but they also include coxsackievirus B4 and adenovirus.5 Mechanical causes such as overexertion or prolonged immobilisation, hypernatraemia from ingestion of sea water, the use of medicinal products, toxins or drugs of abuse, haemoglobinopathies or G6PDH deficiency6,7 can cause or contribute to rhabdomyolysis, with a certain genetic or racial predisposition necessary for it to develop.8 A number of authors have identified cases1–3 arriving in Italy after a one to two-day voyage across the Mediterranean. They are young black patients around the age of 20, up to 20% of them asymptomatic, who are found to have CK elevation an average of 10–36 days following their arrival, according to the authors, and they usually recover about two to three weeks after the onset of symptoms.1–3 The case we have presented here has the same characteristics and, although we cannot rule out mechanical causes, even though it was more than 72 h since the possible overexertion, or certain viruses listed as potential causes, we believe that our case could be included in the clinical spectrum described by these authors.

In conclusion, we believe that migrants with these characteristics have a high risk of rhabdomyolysis and should be studied in this regard, as the complications are potentially serious. We also believe that in a not insignificant number of cases the aetiology cannot be demonstrated, so this phenomenon and its possible relationship with some type of unproven infection, genetic, racial or geographic factor needs to be investigated. Last of all, we need to be aware of the possibility of this condition in African migrants who reach Spain across the sea.

Please cite this article as: Ramos-Paesa C, Huguet-Embún L, Arenas-Miquelez AI, de los Mozos-Ruano A. Fiebre de origen no filiado y rabdomiólisis en una inmigrante procedente de África. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eimc.2019.10.011