Infectious spondylodiscitis (ISD) is aetiologically classified as pyogenic/bacterial, granulomatous (tuberculous, brucellar and fungal) or parasitic.1 The most common route of dissemination in bacterial ISD is haematogenous, it is usually monomicrobial and is preferentially located at the lumbar level (58%).2 Its incidence is increasing due to the greater number of susceptible patients: advanced age, spinal surgery, immunosuppression and use of intravascular and urinary devices.3 There is a significant delay in its diagnosis due to the non-specificity of the symptoms, often with low back pain as the only symptom.

We present a case of ISD due to Serratia marcescens as a complication of a nosocomial urinary infection in a patient with a catheter.

A 76-year-old hypertensive woman on diet therapy suffered an acute ischaemic stroke during her holiday in another autonomous community and was admitted to the nearest referral hospital. One month after admission, during her hospital stay, she presented with bacteraemia of urinary origin (bladder catheter user) due to S. marcescens isolated in urine and blood cultures. We do not know which antibiotic therapy she received or its duration.

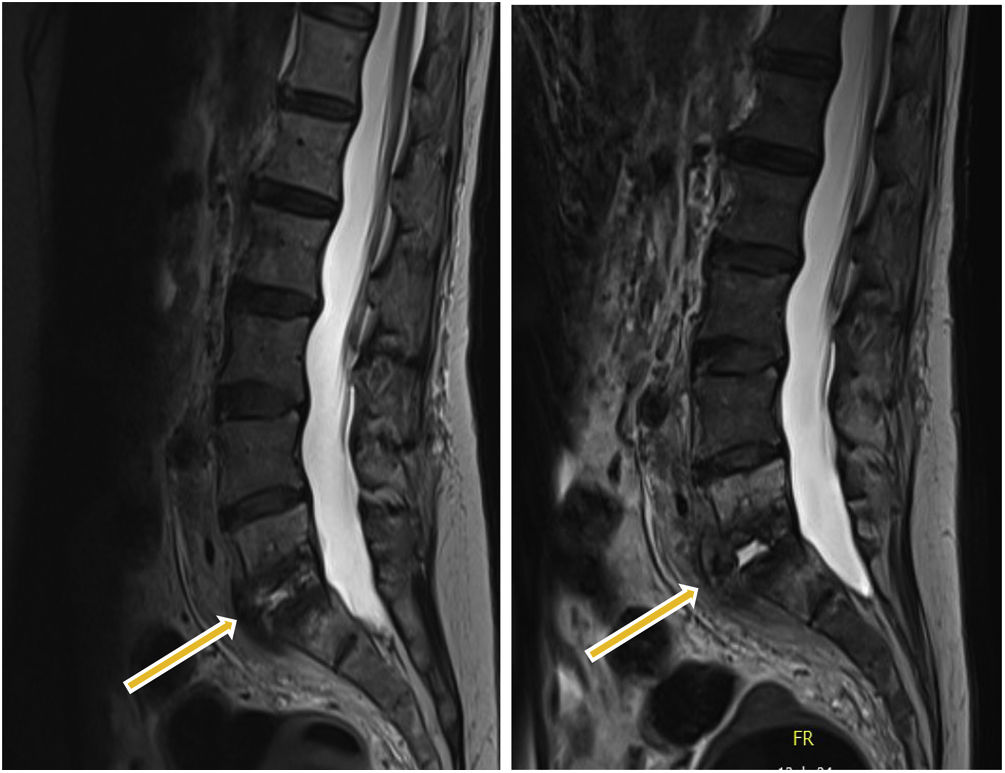

She was transferred to a neurological rehabilitation centre in our community. Thirty days later, she again presented with bacteraemia due to S. marcescens of unknown origin. Endocarditis was ruled out by transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiograms and she was treated with intravenous ertapenem for 14 days. After four months, she began to experience low back pain radiating to the left leg that did not subside with analgesic treatment. An MRI was performed with findings consistent with ISD (L5-S1). She was admitted to the infectious diseases department of our hospital for aetiological study and treatment. Three CT-guided biopsies were obtained, whose aerobic/anaerobic/prolonged culture in enrichment medium/mycobacteria and 16S rRNA gene PCR were negative. During admission, serial blood cultures were obtained with negative results.

After eight weeks on empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, which consisted of combined intravenous therapy of cefepime and daptomycin, she did not exhibit clinical improvement, and the MRI revealed radiological deterioration (Fig. 1). It was decided to perform an open surgical biopsy, and nine samples were sent to our microbiology service.

The direct aerobic/anaerobic culture was negative in the nine samples. Growth was observed after five days in the enrichment medium (BD BBL™Thioglycollate Medium) in only 1/9 samples, which corresponded to a fragment of the L5-S1 disc. In the subculture, S. marcescens was isolated and identified by MALDI-TOF (Bruker® Daltonics). To rule out the possibility of contamination during sample collection and/or processing, the presence of this microorganism was confirmed using the FilmArray® BCID2 sepsis panel. This technique was performed on biopsy in situ after homogenisation with sterilised glass beads and saline solution subjected to vortex mixing. The strain was sensitive to piperacillin/tazobactam, cefepime, carbapenems, aminoglycosides and co-trimoxazole using the BD Phoenix™M50 antibiogram system. Targeted antibiotic therapy with intravenous meropenem (2 g/8 h) was started, but the patient died of secondary complications derived from her underlying diseases.

This case is striking, on the one hand, for the unusual finding of S. marcescens as a causal agent of ISD.4 The most commonly isolated microorganism in ISD continues to be Staphylococcus aureus, although in elderly patients, enterobacterial infections are responsible for 7%–33% of cases,1 the genitourinary tract being the most common focus (29%).3 In this case, the first bacteraemia of urinary origin (bladder catheter user) was the triggering event. For this reason, it is crucial to consider previous microbiological isolates for appropriate antibiotic therapy. Not having access to the clinical history of the hospital centres where the patient was admitted made diagnosis difficult.

On the other hand, in terms of microbiological diagnosis, the frequency of taking osteoarticular samples varies greatly (19%–100%) according to the literature, and it is carried out mainly when blood cultures are negative.1 The diagnostic yield of conventional culture of osteoarticular biopsies is considered highly variable (43%–78%), and it has been reported that the yield is higher in open biopsies (93%) compared to image-guided percutaneous biopsies (48%).5 However, the use of molecular biology techniques, as in our experience, with FilmArray® BCID2 “off-label” directly on biopsy material after sample treatment can increase diagnostic sensitivity in ISD.

As a final conclusion, we would stress the importance of prolonged bacterial culture in enrichment media such as thioglycollate broth or inoculation of the sample in blood culture bottles to increase the yield of diagnostic biopsies. We also recommend the use of new molecular techniques to support conventional diagnosis.

FundingThis study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.